<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Marie-Sophie Germain, 1776

- Composer Sergei Vasilievich Rachmaninoff, 1873

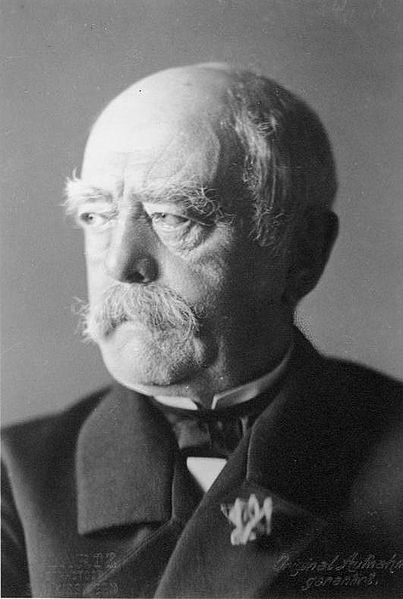

- First Chancellor of the German Empire Otto von Bismarck, 1815

Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck (1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a Prussian/German statesman of the late 19th century, and a dominant figure in world affairs. As Ministerpräsident of Prussia from 1862–1890, he oversaw the unification of Germany. In 1867 he became Chancellor of the North German Confederation. He designed the German Empire in 1871, becoming its first Chancellor and dominating its affairs until his dismissal in 1890. His diplomacy of Realpolitik and powerful rule gained him the nickname "The Iron Chancellor".

After

his death German nationalists made Bismarck their hero, building

hundreds of monuments glorifying the symbol of powerful personal

leadership. Historians praised him as a statesman of moderation and

balance who was primarily responsible for the unification of the German

states into a nation-state. He used balance-of-power diplomacy to keep

Europe peaceful in the 1870s and 1880s. He created a new nation with a

progressive social policy, a result that went beyond his initial goals

as a practitioner of power politics in Prussia. Bismarck, a devout

Lutheran who was obedient to his king, promoted government through a

strong well-trained bureaucracy with a hereditary monarchy at the top. Bismarck

had recognized early in his political career that the opportunities for

national unification would exist and he worked successfully to provide

a Prussian structure to the nation as a whole. On

the other hand, his Reich of 1871 deliberately restricted democracy,

and the anti-Catholic and anti-Socialist legislation that he introduced

unsuccessfully in the 1870s and 1880s left a devastating legacy of

distrust and fragmentation in German political culture. Bismarck was born in Schönhausen, the wealthy family estate situated west of Berlin in the Prussian Province of Saxony. His father, Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand von Bismarck (Schönhausen, 13 November 1771 – 22 November 1845), was a Junker estate owner and a former Prussian military officer; his mother, Wilhelmine Luise Mencken (Potsdam, 24 February 1789 – Berlin), the well-educated daughter of a senior government official in Berlin. A.J.P. Although Bismarck

physically resembled his father, and appeared as a Prussian Junker to

the outside world—an image which he often encouraged by wearing

military uniform, even though he was not a regular officer—he was also

more cosmopolitan and highly educated than was normal for men of such

background. He spoke and wrote English, French, and Russian fluently. As a young man he would often quote Shakespeare or Byron in letters to his wife. Bismarck was educated at the Friedrich-Wilhelm and Graues Kloster secondary schools. From 1832 to 1833 he studied law at the University of Göttingen where he was a member of the Corps Hannovera before enrolling at the University of Berlin (1833–35). Whilst at Göttingen, Bismarck had become the lifelong friend of an American student John Lothrop Motley, who became an eminent historian and diplomat. Although Bismarck hoped to become a diplomat, he started his practical training as a lawyer in Aachen and Potsdam,

and soon resigned, having first placed his career in jeopardy by taking

unauthorized leave to pursue two English girls, first Laura Russell,

niece of the Duke of Cleveland,

and then Isabella Loraine-Smith, daughter of a wealthy clergyman. He

did not succeed in marrying either. He also served in the army for a

year and became an officer in the Landwehr (reserve), before returning to run the family estates at Schönhausen on his mother's death in his mid-twenties. Around

the age of thirty Bismarck had an intense friendship with Marie von

Thadden, newly-married to a friend of his. Under her influence, he

became a Pietist Lutheran,

and later recorded that at Marie's deathbed (from typhoid) he prayed

for the first time since his childhood. Bismarck married Marie's

cousin, the noblewoman Johanna von Puttkamer (Viartlum,

11 April 1824 – Varzin, 27 November 1894) at Alt-Kolziglow on 28 July

1847. Their long and happy marriage produced three children, Herbert (b.

1849), Wilhelm (b. 1852) and Marie (b. 1847). Johanna was a shy,

retiring and deeply religious woman—although famed for her sharp tongue

in later life—and in his public life Bismarck was sometimes accompanied

by his sister Malwine ("Malle") von Arnim. Whilst

on holiday alone in Biarritz in the summer of 1862 (prior to becoming

Prime Minister of Prussia), Bismarck would later have a romantic

liaison with Kathy Orlov, the twenty-two year old wife of a Russian

diplomat—it is not known whether or not their relationship was sexual.

Bismarck kept his wife informed of his new friendship by letter, and in

a subsequent year Kathy broke off plans to meet Bismarck on holiday

again on learning that his wife and family would be accompanying him

this time. They continued to write to one another until Kathy's

premature death in 1874. In

the year of his marriage, 1847, at age 32, Bismarck was chosen as a

representative to the newly created Prussian legislature, the Vereinigter Landtag. There, he gained a reputation as a royalist and reactionary politician with a gift for stinging rhetoric; he openly advocated the idea that the monarch had a divine right to rule.

His election was arranged by the Gerlach brothers, who were also

Pietist Lutherans and whose ultra-conservative faction was known as the

"Kreuzzeitung" after their newspaper, which featured an Iron Cross on

its cover. In March 1848, Prussia faced a revolution (one of the revolutions of 1848 in various European nations), which completely overwhelmed King Frederick William IV.

The monarch, though initially inclined to use armed forces to suppress

the rebellion, ultimately declined to leave Berlin for the safety of

military headquarters at Potsdam. He offered numerous concessions to the liberals:

he wore the black-red-and-gold revolutionary colors (as seen on the

flag of today's democratic Germany), promised to promulgate a

constitution, agreed that Prussia and other states should merge into a

single nation, and appointed a liberal, Ludolf Cam, as

Minister-President. Bismarck

had at first tried to rouse the peasants of his estate into an army to

march on Berlin in the King's name. He traveled to Berlin in disguise

to offer his services, but was instead told to make himself useful by

arranging food supplies for the Army from his estates in case they were

needed. The King's brother Prince William (the future King and Emperor William I) had fled to England, and Bismarck intrigued with William's wife Augusta to place their teenage son (the future Frederick III) on the Prussian throne in King Frederick William IV's

place—Augusta would have none of it, and detested Bismarck thereafter,

although Bismarck did later help to restore a working relationship

between the King and his brother, who were on poor terms. Bismarck was

not a member of the Landtag elected

that year. But the liberal victory perished by the end of the year. The

movement became weak due to internal fighting, while the conservatives

regrouped, formed an inner group of advisers—including the Gerlach

brothers—known as the "Camarilla"

around the King, and retook control of Berlin. Although a constitution

was granted, its provisions fell far short of the demands of the

revolutionaries. In 1849, Bismarck was elected to the Landtag,

the lower house of the new Prussian legislature. At this stage in his

career, he opposed the unification of Germany, arguing that Prussia

would lose its independence in the process. He accepted his appointment

as one of Prussia's representatives at the Erfurt Parliament, an

assembly of German states that met to discuss plans for union, but only

in order to oppose that body's proposals more effectively. The

Parliament failed to bring about unification, for it lacked the support

of the two most important German states, Prussia and Austria.

In 1850, after a dispute over Hesse, Prussia was humiliated and forced

to back down by Austria (supported by Russia) in the so-called Punctation of Olmutz;

a plan for the unification of Germany under Prussian leadership,

proposed by Prussia's Prime Ministers Radowitz, was also abandoned. In 1851, Frederick William appointed Bismarck as Prussia's envoy to the Diet of the German Confederation in Frankfurt. Bismarck gave up his elected seat in the Landtag, but was appointed to the Prussian House of Lords a

few years later. In Frankfurt he engaged in a battle of wills with the

Austrian representative Count Thun, insisting on being treated as an

equal by petty tactics such as insisting on doing the same when Thun

claimed the privileges of smoking and removing his jacket in meetings. Bismarck's

eight years in Frankfurt were marked by changes in his political

opinions, detailed in the numerous lengthy memoranda which he sent to

his ministerial superiors in Berlin. No longer under the influence of

his ultraconservative Prussian friends, Bismarck became less

reactionary and more pragmatic. He became convinced that in order to

countervail Austria's newly-restored influence, Prussia would not only

have to ally herself with other German states. As a result, he grew to

be more accepting of the notion of a united German nation. Bismarck

also worked to maintain the friendship of Russia and a working

relationship with Napoleon III's France—the latter being anathema to

his conservative friends the Gerlachs, but necessary both to threaten

Austria and to prevent France allying herself to Russia. In a famous

letter to Leopold von Gerlach, Bismarck wrote that it was foolish to

play chess having first put 16 of the 64 squares out-of-bounds. This

observation was ironic as after 1871 France would indeed become

Germany's permanent enemy and would indeed eventually ally with Russia

against Germany in the 1890s. Bismarck was also horrified by Prussia's isolation during the Crimean War of

the mid-1850s (in which Austria sided with Britain and France against

Russia and Prussia was almost not invited to the peace talks in Paris).

In the Eastern crisis of the 1870s, fear of a repetition of this turn

of events would later be a factor in Bismarck's signing the Dual

Alliance with Austria-Hungary in 1879. However, in the 1850s Bismarck

correctly foresaw that by failing to support Russia Austria could no longer count on Russian support in Italy

and Germany, and had thus exposed herself to attack by France and

Prussia. In 1858, Frederick William IV suffered a stroke that paralyzed and mentally disabled him. His brother, William,

took over the government of Prussia as regent. At first William was

seen as a moderate ruler, whose friendship with liberal Britain was

symbolised by the recent marriage of his son (the future Frederick III) to Queen Victoria's eldest daughter Vicky; their son (the future Wilhelm II)

was born in 1859. As part of William's "New Course" he brought in new

ministers, moderate conservatives known as the "Wochenblatt" party

after their newspaper. Soon

the Regent replaced Bismarck as envoy in Frankfurt and made him

Prussia's ambassador to the Russian Empire. In theory this was a

promotion as Russia was one of the two most powerful neighbors of

Prussia (the other was Austria). In reality Bismarck was sidelined from

events in Germany, watching impotently as France drove Austria out of

Lombardy during the Italian War of 1859. Bismarck proposed that Prussia

should exploit Austria's weakness to move her frontiers "as far south

as Lake Constance" on the Swiss border; instead Prussia mobilised

troops in the Rhineland to deter further French advances into Venetia.

As a further snub, the Regent, who scorned Bismarck as a "Landwehrleutnant" (reserve lieutenant), had declined to promote him to

the rank of major-general, normal for the ambassador to Saint Petersburg. Bismarck stayed in Saint Petersburg for four

years, during which he almost lost his leg to botched medical treatment

and once again met his future adversary, the Russian Prince Gorchakov, who had been the Russian representative in Frankfurt in the early 1850s. The Regent also appointed Helmuth von Moltke as the new Chief of Staff for the Prussian Army, and Albrecht von Roon as

Prussian Minister of War and to the job of reorganizing the army. These

three people over the next twelve years transformed Prussia. Despite

his lengthy stay abroad, Bismarck was not entirely detached from German

domestic affairs. He remained well-informed due to his friendship with

Roon, and they formed a lasting political alliance. In 1862 Bismarck

was offered a place in the Russian diplomatic service after the Czar

misunderstood a comment about his likelihood to miss Saint Petersburg.

Bismarck courteously declined the offer. In

May 1862, he was sent to Paris, so that he could serve as ambassador to

France. He also visited England that summer. These visits enabled him

to meet and get the measure of his adversaries Napoleon III, and the British Prime Minister Palmerston and Foreign Secretary Earl Russell, and also of the British Conservative politician Disraeli,

later to be Prime Minister in the 1870s—who later claimed to have said

of Bismarck's visit "be careful of that man—he means what he says". The regent became King William I upon

his brother's death in 1861. The new monarch was often in conflict with

the increasingly liberal Prussian Diet. A crisis arose in 1862, when

the Diet refused to authorise funding for a proposed re-organization of

the army. The King's ministers could not convince legislators to pass

the budget, and the King was unwilling to make concessions. Wilhelm

threatened to abdicate (though his son was opposed to his abdication)

and believed that Bismarck was the only politician capable of handling

the crisis. However, Wilhelm was ambivalent about appointing a person

who demanded unfettered control over foreign affairs. When, in

September 1862, the Abgeordnetenhaus (House

of Deputies) overwhelmingly rejected the proposed budget, Wilhelm was

persuaded to recall Bismarck to Prussia on the advice of Roon. On 23

September 1862, Wilhelm appointed Bismarck Minister-President and Foreign Minister. The

change of Bismarck, Roon and Moltke occurred at a time when relations

among the Great Powers—Great Britain, France, Austria and Russia—had

been shattered by the Crimean War of 1854–55 and the Italian War of 1859. In the midst of this disarray, the European balance of power was restructured with the creation of the German Empire as

the dominant power in Europe. This was achieved by Bismarck's

diplomacy, by Roon's reorganization of the army, and by Moltke's

military strategy. Despite

the initial distrust of the King and Crown Prince, and the loathing of

Queen Augusta, Bismarck soon acquired a powerful hold over the King by

force of personality and powers of persuasion. Bismarck was intent on

maintaining royal supremacy by ending the budget deadlock in the King's

favour, even if he had to use extralegal means to do so. He contended

that, since the Constitution did not provide for cases in which

legislators failed to approve a budget, he could merely apply the

previous year's budget. Thus, on the basis of the budget of 1861, tax

collection continued for four years. Bismarck's conflict with the legislators grew more heated during the following years. Following the Alvensleben Convention of

1863, the House of Deputies passed a resolution declaring that it could

no longer come to terms with Bismarck; in response, the King dissolved

the Diet, accusing it of trying to obtain unconstitutional control over

the ministry. Bismarck then issued an edict restricting the freedom of

the press; this policy even gained the public opposition of the Crown

Prince, Friedrich Wilhelm (the

future Emperor Friedrich III). Despite attempts to silence critics,

Bismarck remained a largely unpopular politician. His supporters fared

poorly in the elections of October 1863, in which a liberal coalition

(whose primary member was the Progress Party)

won over two-thirds of the seats in the House. The House made repeated

calls to the King to dismiss Bismarck, but the King supported him as he

feared that if he dismissed Bismarck, a liberal ministry would follow. German unification had been one of the major objectives during the widespread revolutions of 1848–49, when representatives of the German states met in Frankfurt and

drafted a constitution creating a federal union with a national

parliament to be elected by universal male suffrage. In April 1849, the Frankfurt Parliament offered the title of Emperor to the Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm IV.

The Prussian king, fearing the opposition of the other German princes

and the military intervention of Austria and Russia, refused to accept

this popular mandate. Thus, the Frankfurt Parliament ended in failure for the German liberals. Germany prior to the 1860s consisted of a multitude of principalities loosely bound together as members of the German Confederation.

Bismarck used both diplomacy and the Prussian military to achieve

unification, excluding Austria from unified Germany. Not only did he

make Prussia the most powerful and dominant component of the new

Germany, but he also ensured that Prussia would remain an authoritarian

state, rather than a liberal parliamentary regime. Bismarck faced a diplomatic crisis when Frederick VII of Denmark died in November 1863. Succession to the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein was disputed; they were claimed by Christian IX (Frederick VII's heir as King) and by Frederick von Augustenburg (a

German duke). Prussian public opinion strongly favoured Augustenburg's

claim, as Holstein and southern Schleswig were (and are)

German-speaking. Bismarck took an unpopular step by insisting that the

territories legally belonged to the Danish monarch under the London Protocol signed

a decade earlier. Nonetheless, Bismarck did denounce Christian's

decision to completely annex Schleswig to Denmark. With support from

Austria, he issued an ultimatum for Christian IX to return Schleswig to

its former status; when Denmark refused, Austria and Prussia invaded,

commencing the Second war of Schleswig and Denmark was forced to cede both duchies. Britain under Prime Minister Palmerston and Foreign Secretary Earl Russell was humiliated and left impotent, as she was unwilling to commit ground troops to Denmark. At

first this seemed like a victory for Augustenberg, but Bismarck soon

removed him from power by making a series of unworkable demands, namely

that Prussia should have control over the army and navy of the Duchies.

Originally, it was proposed that the Diet of the German Confederation

should determine

the fate of the duchies; but before this scheme could be effected,

Bismarck induced Austria to agree to the Gastein Convention.

Under this agreement signed 20 August 1865, Prussia received Schleswig,

while Austria received Holstein. In that year he was made Graf (Count) von Bismarck-Schönhausen. But

in 1866, Austria reneged on the prior agreement by demanding that the

Diet determine the Schleswig-Holstein issue. Bismarck used this as an

excuse to start a war with Austria by charging that the Austrians had

violated the Convention of Gastein. Bismarck sent Prussian troops to

occupy Holstein. Provoked, Austria called for the aid of other German

states, who quickly became involved in the Austro-Prussian War. With the aid of Albrecht von Roon's army reorganization, the Prussian army was nearly equal in numbers to the Austrian army. With the organizational genius of Helmuth von Moltke the Elder,

the Prussian army fought battles it was able to win. Bismarck had also

made a secret alliance with Italy, who desired Austrian-controlled

Venetia. Italy's entry into the war forced the Austrians to divide

their forces. As the war began, a German radical named Ferdinand Cohen-Blind attempted

to assassinate Bismarck in Berlin, shooting him five times at close

range. Cohen-Blind was a democrat who hoped that killing Bismarck would

prevent a war among the German states. Bismarck survived with only

minor injuries despite having been shot five times; Cohen-Blind

committed suicide while in custody. To the surprise of the rest of

Europe, Prussia quickly defeated Austria and its allies, at the Battle of Königgrätz (aka

"Battle of Sadowa"). The King and his generals wanted to push on,

conquer Bohemia and march to Vienna, but Bismarck, worried that

Prussian military luck might change or that France might intervene on

Austria's side, enlisted the help of the Crown Prince (who had opposed

the war but had commanded one of the Prussian armies at Sadowa) to

change his father's mind after stormy meetings. As a result of the Peace of Prague (1866), the German Confederation was dissolved; Prussia annexed Schleswig, Holstein, Frankfurt, Hanover, Hesse-Kassel (or Hesse-Cassel), and Nassau;

and Austria promised not to intervene in German affairs. To solidify

Prussian hegemony, Prussia and several other North German states joined

the North German Confederation in

1867; King Wilhelm I served as its President, and Bismarck as its

Chancellor. From this point on begins what historians refer to as "The

Misery of Austria", in which Austria served as a mere vassal to the superior Germany, a relationship that was to shape history up to the two World Wars. Bismarck,

who by now held the rank of major in the Landwehr, wore this uniform

during the campaign, and was at last promoted to the rank of

major-general in the Landwehr cavalry after the war. Although he never

personally commanded troops in the field, he usually wore a general's

uniform in public for the rest of his life, as seen in numerous

paintings and photographs. He was also given a cash grant by the

Prussian Landtag, which he used to buy a new country estate, Varzin,

larger than his existing estates combined. Military

success brought Bismarck tremendous political support in Prussia. In

the elections to the House of Deputies in 1866, liberals suffered a

major defeat, losing their large majority. The new, largely

conservative House was on much better terms with Bismarck than previous

bodies; at the Minister-President's request, it retroactively approved

the budgets of the past four years, which had been implemented without

parliamentary consent. Following

the 1866 war, Prussia annexed the Kingdom of Hanover, which had been

allied with Austria against Prussia. An agreement was reached whereby

the deposed King George V of Hanover was

allowed to keep about 50% of the crown assets. The rest were deemed to

be state assets and were transferred to the national treasury.

Subsequently Bismarck accused George of organizing a plot against the

state and sequestered his share (16 million thalers)

in early 1868. Bismarck used this money to set up a secret fund (the

"Reptilienfonds" or Reptiles Fund), which he used to bribe journalists

and to discredit his political enemies. In 1870 he used some of these

funds to win the support of King Ludwig II of Bavaria for making William I German Emperor. Bismarck also used these funds to place informers in the household of Crown Prince Frederick and his wife Victoria.

Some of the bogus stories that Bismarck planted in newspapers accused

the royal couple of acting as British agents by revealing state secrets

to the British government. Frederick and Victoria were great admirers

of her father Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, prince consort of Victoria of the United Kingdom. They planned to rule as consorts, like Albert and Victoria. Frederick "described the Imperial Constitution as ingeniously contrived chaos." The

office of Chancellor responsible to the Kaiser would be replaced with a

cabinet based on the British style, with ministers responsible to the

Reichstag. Government policy would be based on the consensus of the

cabinet. In

order to undermine the royal couple, when the future Kaiser William II

was still a teenager, Bismarck would separate him from his parents and

would place him under his tutelage. Bismarck planned to use William as

a weapon against his parents in order to retain his own power. Bismarck

would drill William on his prerogatives and would teach him to be

insubordinate to his parents. Consequently, William II developed a

dysfunctional relationship with his father and especially with his

English mother. In

1892, after Bismarck's dismissal, Kaiser William II stopped the use of

the fund by releasing the interest payments into the official budget. Prussia's victory over Austria increased tensions with France. The French Emperor, Napoleon III, feared that a powerful Germany would change the balance of power in Europe. Bismarck, at the same time, did not avoid war with France.

He believed that if the German states perceived France as the

aggressor, they would unite behind the King of Prussia. In order to

achieve this Bismarck kept Napoleon III involved in various intrigues

whereby France might gain territory from Luxembourg or Belgium - France

never achieved any such gain, but was made to look greedy and

untrustworthy. A suitable premise for war arose in 1870, when the German Prince Leopold of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen was

offered the Spanish throne, which had been vacant since a revolution in

1868. France blocked the candidacy and demanded assurances that no

member of the House of Hohenzollern become King of Spain. To provoke France into declaring war with Prussia, Bismarck published the Ems Dispatch,

a carefully edited version of a conversation between King Wilhelm and

the French ambassador to Prussia, Count Benedetti. This conversation

had been edited so that each nation felt that its ambassador had been

disrespected and ridiculed, thus inflaming popular sentiment on both

sides in favor of war. France

mobilized and declared war on 19 July, five days after the dispatch was

published in Paris. It was seen as the aggressor and German states,

swept up by nationalism and patriotic zeal, rallied to Prussia's side

and provided troops. After all, it came as a sort of deja vu: current

french public musings of the river Rhine as "the natural french border"

and the memory of the french revolutionary/Napoleonic wars 1790/1815 was still alive. Russia

remained aloof and used the opportunity to remilitarise the Black Sea,

demilitarised after the Crimean War of the 1850s. Both of Bismarck's

sons served as officers in the Prussian cavalry. The Franco-Prussian War (1870) was a great success for Prussia. The German army, under nominal command of the King but controlled by Chief of Staff Helmuth von Moltke the Elder, won victory after victory. The major battles were all fought in one month (7 August till 1 September), and both French armies were captured at Sedan and Metz,

the latter after a siege of some weeks. The remainder of the war featured a siege of Paris, the city was

”ineffectually bombarded”; the

new French republican regime then tried, without success, to relieve

Paris with various hastily assembled armies and increasingly bitter

partisan warfare. Bismarck

acted immediately to secure the unification of Germany. He negotiated

with representatives of the southern German states, offering special

concessions if they agreed to unification. The negotiations succeeded;

while the war was in its final phase King Wilhelm of Prussia was proclaimed 'German Emperor' on 18 January 1871 in the Hall of Mirrors in the Château de Versailles. The new German Empire was a federation:

each of its 25 constituent states (kingdoms, grand duchies, duchies,

principalities, and free cities) retained some autonomy. The King of

Prussia, as German Emperor, was not sovereign over the entirety of

Germany; he was only primus inter pares, or first among equals. But he held the presidency of the Bundesrat, which met to discuss policy presented from the Chancellor (whom the president appointed). At the end, France had to surrender Alsace and part of Lorraine, because Moltke and his generals insisted that it was needed as a defensive barrier. Bismarck opposed the annexation because he did not wish to make a permanent enemy of France. France was also required to pay an indemnity. In 1871, Otto von Bismarck was raised to the rank of Fürst (Prince) von Bismarck.

He was also appointed Imperial Chancellor of the German Empire, but

retained his Prussian offices (including those of Minister-President

and Foreign Minister). He was also promoted to the rank of

lieutenant-general, and given another country estate, Friedrichsruh,

near Hamburg, which was larger than Varzin, making him a very wealthy

landowner. Because of both the imperial and the Prussian offices that

he held, Bismarck had near complete control over domestic and foreign

policy. The office of Minister-President (M-P) of Prussia was

temporarily separated from that of Chancellor in 1873, when Albrecht

von Roon was appointed to the former office. But by the end of the

year, Roon resigned due to ill health, and Bismarck again became M-P. In

the following years, one of Bismarck's primary political objectives was

to reduce the influence of the Catholic Church in Germany. This may

have been due to the anti-liberal message of Pope Pius IX in the Syllabus of Errors of 1864, and especially to the dogma of Papal infallibility (1870). Bismarck

feared that Pope Pius IX and future popes would use the definition of

the doctrine of their infallibility as a political weapon for creating

instability by driving a wedge between Catholics and Protestants. To

prevent this, Bismarck attempted, without success, to reach an

understanding with other European governments, whereby future papal

elections would be manipulated. The European governments would agree on

unsuitable papal candidates, and then instruct their national cardinals

to vote in the appropriate manner. Prussia (except the Rhineland) and most other northern German states were predominantly Protestant, but many Catholics lived in the southern German states (especially Bavaria).

In total, approximately one third of the population was Catholic.

Bismarck believed that the Roman Catholic Church held too much

political power; he was further concerned about the emergence of the Catholic Centre Party (organised in 1870). Accordingly, he began an anti-Catholic campaign known as the Kulturkampf. In 1871, the Catholic Department of the Prussian Ministry of Culture was abolished. In 1872, the Jesuits were

expelled from Germany. More severe anti-Roman Catholic laws of 1873

allowed the government to supervise the education of the Roman Catholic

clergy, and curtailed the disciplinary powers of the Church. In 1875,

civil ceremonies were required for weddings, which could hitherto be

performed in churches. These efforts strengthened the Catholic Centre

Party, and Bismarck abandoned the Kulturkampf in 1878 to preserve his remaining political capital. Pius died that same year, replaced by a more pragmatic Pope Leo XIII who would eventually establish a better relationship with Bismarck. The Kulturkampf had won Bismarck a new supporter in the secular National Liberal Party, which had become Bismarck's chief ally in the Reichstag. But in 1873, Germany and much of Europe had entered the Long Depression beginning with the crash of the Vienna Stock Exchange in 1873, the Gründerkrise.

A downturn hit the German economy for the first time since vast

industrial development in the 1850s after the 1848–49 revolutions. To

aid faltering industries, the Chancellor abandoned free trade and established protectionist tariffs, which alienated the National Liberals who supported free trade. The Kulturkampf and

its effects also stirred up public opinion against the party that

supported it, and Bismarck used this opportunity to distance himself

from the National Liberals. This marked a rapid decline in the support

of the National Liberals, and by 1879 their close ties with Bismarck

had all but ended. Bismarck instead returned to conservative factions —

including the Centre Party — for support. He helped foster support from

the conservatives by enacting several tariffs protecting German

agriculture and industry from foreign competitors in 1879. To prevent the Austro-Hungarian problems of different nationalities within one state, the government tried to Germanize the

state's national minorities, situated mainly in the borders of the

empire, such as the Danes in the North of Germany, the French of

Alsace-Lorraine and the Poles in the East of Germany. His policies concerning the Poles of Prussia were generally unfavourable to them, furthering

enmity between the German and Polish peoples. The policies were usually

motivated by Bismarck's view that Polish existence was a threat to

German state; Bismarck, who himself spoke Polish, wrote about Poles: "One shoots the wolves if one can." He

also said: "Beat Poles until they lose faith in sense of living.

Personally, I pity the situation they're in. However, if we want to

survive -we've got only one option - to exterminate them. Bismarck worried about the growth of the socialist movement — in particular, that of the Social Democratic Party. In 1878, he instituted the Anti-Socialist Laws.

Socialist organizations and meetings were forbidden, as was the

circulation of socialist literature. Socialist leaders were arrested

and tried by police courts. But despite these efforts, the movement

steadily gained supporters and seats in the Reichstag. Socialists won

seats in the Reichstag by running as independent candidates,

unaffiliated with any party, which was allowed by the German

Constitution. Then

the Chancellor tried to reduce the appeal of socialism to the public by

trying to appease the working classes. He enacted a variety of social

programs. Bismarck’s social insurance legislations were the first in

the world and became the model for other countries. The

Health Insurance Act of 1883 entitled workers to health insurance.

Accident insurance was provided in 1884, old age pensions and

disability insurance in 1889, he even thought of insurance for

unemployment. Other

laws restricted the employment of women and children. Irrespective of

these progressive programs, the working classes largely remained

unreconciled with Bismarck's conservative government.

Bismarck had unified his nation and now he devoted himself to promoting peace in

Europe with his skills in statesmanship. He was forced to contend with

French revanchism —

the desire to avenge the loss in the Franco-Prussian War. Bismarck

therefore engaged in a policy of diplomatically isolating France while

maintaining cordial relations with other nations in Europe. Bismarck

had little interest in naval or colonial entanglements and thus avoided

discord with the United Kingdom. In 1872, he offered friendship to the

Austro-Hungarian Empire and Russia, whose rulers joined Wilhelm I in the League of the Three Emperors, also known as the Dreikaiserbund. Also

in 1872, a protracted quarrel began to fester between Bismarck and

Count Harry von Arnim, a career diplomat and the imperial ambassador to

France. Arnim was a member of a prominent Pomeranian family, related to

Bismarck by marriage, and someone who saw himself as a rival and

competitor for the chancellorship. The ambassador disagreed

unsuccessfully with Bismarck over policy vis-à-vis France. As a

penalty for this indiscretion, Bismarck intended to remove Arnim from

Paris and reassign him as ambassador to the Ottoman Empire at

Constantinople, which given the relative importance of France to

Germany as compared with that of the Ottoman Empire, was seen by Arnim

as a demotion. Arnim refused and continued to put forth his views in

opposition to Bismarck, going so far as to remove sensitive records

from embassy files at Paris to back up his attacks on Bismarck. The

controversy lasted on for two years with Arnim being ‘protected’ by

powerful friends before he was formally accused of misappropriating

official documents, indicted, tried, and convicted. While his sentence

was under appeal, he fled to Switzerland and died in exile. After this

episode, no-one again openly challenged Bismarck in foreign policy

matters until his resignation.

By 1875 France had recovered from defeat in the Franco-Prussian War and

a new government began to militarily expand and reassert itself again

as a player in European politics. The German general staff under Moltke

was alarmed and managed to have Bismarck ban a French procurement of

ten thousand cavalry horses from Germany. There followed some informal

debate of the necessity of preventive war. The printing by a prominent

newspaper of an article entitled "Is War in Sight?" caused a crisis to

develop that was not to Bismarck’s advantage. The British government

dispatched a polite warning to Berlin. Russia’s Tsar Alexander II and

his chancellor Prince Gorchakov,

at the time on a state visit to Germany, seized the opportunity to

inject themselves as European peace makers. This action initiated a

lasting estrangement between Bismarck and Gorchakov over the latter’s

‘interference’ in a Franco-German spat. Between

1873 and 1877 Germany repeatedly intervened in the internal affairs of

France's neighbors. In Belgium, Spain, and Italy, Bismarck exerted

strong and sustained political pressure to support the election or

appointment of liberal, anticlerical governments. This was not merely a

by-product of the Kulturkampf but part of an integrated strategy to

promote republicanism in France by strategically and ideologically isolating the clerical-monarchist regime of President Marie Edme MacMahon (1808-93).

It was hoped that by ringing France with a number of liberal states,

French republicanism could defeat MacMahon and his reactionary

supporters. Bismarck maintained good relations with Italy, although he had a personal dislike for Italians and their country. He can be seen as marginal contributor to Italian Unification. Politics surrounding the 1866 war against Austria allowed Italy to annex Lombardy-Venetia, which had been a kingdom of the Austrian Empire since the 1815 Congress of Vienna.

In addition, French mobilization for the Franco-Prussian War of

1870–1871 made it necessary for Napoleon III to withdraw his troops

from Rome and The Papal States. Without these two events, Italian unification would have been a more prolonged process. After Russia's victory over the Ottoman Empire in the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878), Bismarck helped negotiate a settlement at the Congress of Berlin. The Treaty of Berlin, 1878, revised the earlier Treaty of San Stefano,

reducing the size of newly-independent Bulgaria (a pro-Russian state at

that time). Bismarck and other European leaders opposed the growth of

Russian influence and tried to protect the potency of the Ottoman

Empire.

As a result, Russo-German relations further suffered, with the Russian

chancellor Gorchakov denouncing Bismarck for compromising his nation's

victory. The relationship was additionally strained due to Germany's

protectionist trade policies. The League of the Three Emperors having fallen apart, Bismarck negotiated the Dual Alliance (1879) with Austria-Hungary, in which each guaranteed the other against Russian attack. This became the Triple Alliance in

1882 with the addition of Italy, while Italy and Austria-Hungary soon

reached the "Mediterranean Agreement" with Britain. Attempts to

reconcile Germany and Russia did not have lasting effect: the Three

Emperors' League was re-established in 1881, but quickly fell apart

(the end of the Russian-Austrian-Prussian solidarity which had existed

in various forms since 1813), and the Reinsurance Treaty of

1887 (in which both powers promised to remain neutral towards one

another unless Russia attacked Austria-Hungary) was allowed to expire

in 1890 after Bismarck’s departure.

Bismarck

all along opposed colonial acquisitions, arguing that the burden of

obtaining, maintaining and defending such possessions would outweigh

any potential benefit. But during the late 1870s and early 1880s public

opinion shifted to favor colonies, and Bismarck converted to the

colonial idea. "The pretext was economic." Bismarck was influenced by Hamburg merchants and traders, his neighbors at Friedrichsruh, "and the creation of Germany’s colonial empire proceeded with the minimum of friction." Other

European nations, with Britain and France in the lead, had earlier and

rapidly acquired colonies. During the 1880s, Germany joined the

European powers in the Scramble for Africa. Among Germany's colonies were Togoland (now part of Ghana and Togo), Cameroon, German East Africa (now Rwanda, Burundi, and Tanzania), and German South-West Africa (now Namibia). The Berlin Conference (1884–1885)

established regulations for the acquisition of African colonies; in

particular, it protected free trade in certain parts of the Congo basin. Germany later also acquired colonies in the Pacific. In February 1888, during a Bulgarian crisis, Bismarck addressed the Reichstag on the dangers of a European war. Bismarck

also repeated his emphatic warning against any German military

involvement in Balkan disputes. In 1888, the German Emperor, Wilhelm I, died leaving the throne to his son, Friedrich III. The new monarch was already suffering from an incurable throat cancer and died after reigning for only three months. He was replaced by his son, Wilhelm II.

The new Emperor opposed Bismarck's careful foreign policy, preferring

vigorous and rapid expansion to protect Germany's "place in the sun". Conflicts

between Wilhelm II and his chancellor soon poisoned their relationship.

Bismarck believed that he could dominate Wilhelm, and showed little

respect for his policies in the late 1880s. Their final split occurred

after Bismarck tried to implement far-reaching anti-Socialist laws in

early 1890. Kartell majority

in the Reichstag, of the amalgamated Conservative Party and the

National Liberal Party, was willing to make most of the laws permanent.

But it was split about the law allowing the police the power to expel

socialist agitators from their homes, a power used excessively at times

against political opponents. The National Liberals refused to make this

law permanent, while the Conservatives supported only the entirety of

the bill and threatened to and eventually vetoed the entire bill in

session because Bismarck wouldn't agree to a modified bill. As

the debate continued, Wilhelm became increasingly interested in social

problems, especially the treatment of mine workers who went on strike

in 1889, and keeping with his active policy in government, routinely

interrupted Bismarck in Council to make clear his social policy.

Bismarck sharply disagreed with Wilhelm's policy and worked to

circumvent it. Even though Wilhelm supported the altered anti-socialist

bill, Bismarck pushed for his support to veto the bill in its entirety.

But when his arguments couldn't convince Wilhelm, Bismarck became

excited and agitated until uncharacteristically blurting out his motive

to see the bill fail: to have the socialists agitate until a violent

clash occurred that could be used as a pretext to crush them. Wilhelm

replied that he was not willing to open his reign with a bloody

campaign against his own subjects. The next day, after realizing his

blunder, Bismarck attempted to reach a compromise with Wilhelm by

agreeing to his social policy towards industrial workers, and even

suggested a European council to discuss working conditions, presided by

the German Emperor. Despite

this, a turn of events eventually led to his distancing from Wilhelm.

Bismarck, feeling pressured and unappreciated by the Emperor and

undermined by ambitious advisers, refused to sign a proclamation

regarding the protection of workers along with Wilhelm, as was required

by the German Constitution, to protest Wilhelm's ever increasing

interference to Bismarck's previously unquestioned authority. Bismarck

also worked behind the scenes to break the Continental labour council

on which Wilhelm had set his heart. The final break came as Bismarck searched for a new parliamentary majority, with his Kartell voted from power due to the anti-socialist bill fiasco. The remaining forces in the Reichstag were the Catholic Centre Party and the Conservative Party. Bismarck wished to form a new block with the Centre Party, and invited Ludwig Windthorst,

the parliamentary leader to discuss an alliance. This would be

Bismarck's last political manoeuvre. Wilhelm was furious to hear about

Windthorst's visit. In a parliamentary state, the head of government

depends on the confidence of the parliamentary majority, and certainly

has the right to form coalitions to ensure his policies a majority.

However, in Germany, the Chancellor depended

on the confidence of the Emperor alone, and Wilhelm believed that the

Emperor had the right to be informed before his minister's meeting.

After a heated argument in Bismarck's office Wilhelm, whom Bismarck had

allowed to see a letter from Tsar Alexander III describing him as a

"badly brought-up boy", stormed out, after first ordering the

rescinding of the Cabinet Order of 1851, which had forbidden Prussian

Cabinet Ministers to report directly to the King of Prussia, requiring

them instead to report via the Prime Minister. Bismarck, forced for the

first time into a situation he could not use to his advantage, wrote a

blistering letter of resignation, decrying Wilhelm's interference in

foreign and domestic policy, which was only published after Bismarck's

death. Bismarck

resigned at Wilhelm II's insistence in 1890, at age 75, to be succeeded

as Chancellor of Germany and Minister-President of Prussia by Leo von Caprivi.

Bismarck was discarded, promoted to the rank of "Colonel-General with the

Dignity of Field Marshal" (so-called because the German Army did not

appoint full Field Marshals in peacetime) and given a new title, Duke

of Lauenburg, which he joked would be useful when travelling incognito.

He was soon elected as a National Liberal to the Reichstag for

Bennigsen's old and supposedly safe Hamburg seat, but was embarrassed

by being forced to a second ballot by a Social Democrat rival, and

never actually took up his seat. He entered into restless, resentful

retirement to his estates at Varzin (in today's Poland). Within one month after his wife died on 27 November 1894, he moved to Friedrichsruh near Hamburg, waiting in vain to be petitioned for advice and counsel. As soon as he had to leave his office, citizens started to praise him, collecting money to build monuments like the Bismarck Memorial or towers dedicated

to him. Much honour was given to him in Germany, many buildings have

his name, books about him were best-sellers, and he was often painted,

e.g., by Franz von Lenbach and C.W. Allers. Bismarck spent his final years gathering his memoirs (Gedanken und Erinnerungen, or Thoughts and Memories),

which criticized and discredited the Emperor. He died in 1898 (at the

age of 83) at Friedrichsruh, where he is entombed in the

Bismarck Mausoleum. He was succeeded as Fürst von

Bismarck-Schönhausen by Herbert. On his gravestone it is written "Loyal German Servant of Kaiser William I".