<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Benjamin Peirce, 1809

- Bluesman Muddy Waters, 1805

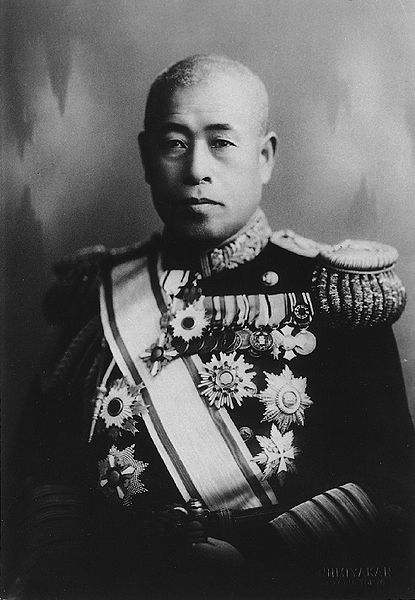

- Naval Marshal General Isoroku Yamamoto, 1884

Isoroku Yamamoto (4 April 1884–18 April 1943) was Naval Marshal General and the commander-in-chief of theCombined Fleet during World War II, a graduate of the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy and a student of the U.S. Naval War College and of Harvard University (1919–1921).

Yamamoto

held several important posts in the Imperial Japanese Navy, and

undertook many of its changes and reorganizations, especially its

development of naval aviation. He was the commander-in-chief during the

decisive early years of the Pacific War and so was responsible for major battles such as Pearl Harbor and Midway. He died during an inspection tour of forward positions in the Solomon Islands when his aircraft (a Mitsubishi G4M "Betty" bomber) was shot down during an ambush by American P-38 Lightning fighter planes. His death was a major blow to Japanese military morale during World War II. Yamamoto was born as Isoroku Takano in Nagaoka, Niigata. His father was Sadayoshi Takano, an intermediate samurai of the Nagaoka Domain.

"Isoroku" is an old Japanese term meaning "56"; the name referred to

his father's age at Isoroku's birth. In 1916, Isoroku was adopted into

the Yamamoto family (another

family of former Nagaoka samurai) and took the Yamamoto name. It was a

common practice for Japanese families lacking sons to adopt suitable

young men in this fashion to carry on the family name. In 1918 Isoroku

married Reiko Mihashi, with whom he had two sons and two daughters.

After graduating from the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy in 1904, Yamamoto served on the cruiser Nisshin during the Russo-Japanese War. He was wounded at the Battle of Tsushima,

losing two fingers (the index and middle fingers) on his left hand. He

returned to the Naval Staff College in 1914, emerging as a Naval Major in 1916. Yamamoto was a political dove who was fundamentally opposed to war with the United States by reason of his studies at Harvard University (1919–1921) and his two postings as a naval attaché in Washington, D.C., among other things. He was promoted to Naval Colonel in 1923. In 1924, at the age of 40, he changed his specialty from gunnery to naval aviation. His first command was the cruiserIsuzu in 1928, followed by the aircraft carrier Akagi.

He participated in the second London Naval Conference of 1930 as a Naval Major-General and the 1934 London Naval Conference as a Naval Lieutenant-General,

as the government felt that a career military specialist needed to

accompany the diplomats to the arms limitations talks. Yamamoto was a

strong proponent of naval aviation, and served as head of the Aeronautics Department before accepting a post as commander of the First Carrier Division. Yamamoto personally opposed the invasion of Manchuria in 1931, the subsequent land war with China (1937), and the 1940 Tripartite Pact with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. As Deputy Navy Minister, he apologized to United States Ambassador Joseph C. Grew for the bombing of the gunboat USS Panay in December 1937. These issues made him a target of assassination by pro-war militarists. Throughout

1938, many young army and naval officers began to speak publicly

against Yamamoto and certain other Japanese admirals such as Yonai and Inouye for

their strong opposition towards a Tripartite pact with Nazi Germany for

reportedly being against "Japan's natural interests." Yamamoto

himself received a steady stream of hate mail and death threats from

Japanese nationalists but his reaction to the prospect of death by

assassination was passive and accepting. The Japanese army, annoyed at Yamamoto's unflinching opposition to a Rome-Berlin-Tokyo treaty, dispatched military police to "guard" Yamamoto; this was an attempt by the Army to keep an eye on him. He was later reassigned from the Navy Ministry to sea as the Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet on (30 August 1939). This was done as one of the last acts of the then-acting Navy Minister Mitsumasa Yonai, under Baron Hiranuma's

short-lived administration partly to make it harder for assassins to

target Yamamoto; Yonai was certain that if Yamamoto remained ashore, he

would be killed before the year (1939) ended. Yamamoto was promoted to Naval General on 15 November 1940. This in spite of the fact that when Hideki Tōjō was

appointed Prime Minister on 18 October 1941, many political observers

thought that Yamamoto's career was essentially over. Tōjō had been

Yamamoto's old opponent from the time when the latter served as Japan's

deputy navy minister and Tōjō was the prime mover behind Japan's

takeover of Manchuria.

It was believed that Yamamoto would be appointed to command the

Yokosuka Naval Base, "a nice safe demotion with a big house and no

power at all." After

the new Japanese cabinet was announced, however, Yamamoto found himself

left alone in his position despite his open conflicts with Tōjō and

other members of the army's oligarchy who favored war with the European

powers and America. Two of the main reasons for Yamamoto's political

survival were his immense popularity within the navy fleet, where he

commanded the respect of his men and officers, and his close relations

with the imperial family. Emperor Hirohito, like Yamamoto, shared a deep respect for the West. Consequently,

Yamamoto stayed in his post. With Tōjō now in charge of Japan's highest

political office, it became clear the army would lead the navy into a

war about which Yamamoto had serious reservations. Yamamoto accepted the

reality of impending war and planned for a quick victory by destroying

the US fleet at Pearl Harbor while simultaneously thrusting into the

oil and rubber resource rich areas of Southeast Asia, especially the

Dutch East Indies, Borneo and Malaya. In naval matters, Yamamoto

opposed the building of the super-battleships Yamato and Musashi as an unwise investment of resources. Yamamoto was responsible for a number of innovations in Japanese naval aviation.

Although remembered for his association with aircraft carriers due to

Pearl Harbor and Midway, Yamamoto did more to influence the development

of land-based naval aviation, particularly the Mitsubishi G3M and G4M medium bombers. His demand for great range and the ability to carry a torpedo was intended to conform to Japanese conceptions of attriting the American fleet as it advanced across the Pacific in

war. The planes did achieve long range, but long-range fighter escorts

were not available. These planes were lightly constructed and when

fully fueled, they were especially vulnerable to enemy fire. This

earned the G4M the sardonic nick-name "the Flying Cigarette Lighter."

Yamamoto would eventually die in one of these aircraft. The

range of the G3M and G4M contributed to a demand for great range in a

fighter aircraft. This partly drove the requirements for the A6M Zero which

was as noteworthy for its range as for its maneuverability. Both

qualities were again purchased at the expense of light construction and

flammability that later contributed to the A6M's high casualty rates as

the war progressed. As

Japan moved toward war during 1940, Yamamoto gradually moved toward

strategic as well as tactical innovation, again with mixed results.

Prompted by talented young officers such as Minoru Genda, Yamamoto approved the reorganization of Japanese carrier forces into the First Air Fleet,

a consolidated striking force that gathered Japan's six largest

carriers into one unit. This innovation gave great striking capacity,

but also concentrated the vulnerable carriers into a compact target;

both boon and bane would be realized in war. Yamamoto also oversaw the

organization of a similar large land-based organization in the 11th Air

Fleet, which would later use the G3M and G4M to neutralize American air

forces in the Philippines and sink the British Force "Z". In

January 1941, Yamamoto went even further and proposed a radical

revision of Japanese naval strategy. For two decades, in keeping with

the doctrine of Captain Alfred T. Mahan, the Naval General Staff had planned in terms of Japanese light surface forces, submarines and land-based air units whittling down the American Fleet as it advanced across the Pacific until the Japanese Navy engaged it in a climactic "Decisive Battle" in the northern Philippine Sea (between the Ryukyu Islands and the Marianas Islands), with battleships meeting in the traditional exchange between battle lines. Correctly

pointing out this plan had never worked even in Japanese war games, and

painfully aware of American strategic advantages in military productive

capacity, Yamamoto proposed instead to seek a decision with the

Americans by first reducing their forces with a preemptive strike, and

following it with a "Decisive Battle" sought offensively, rather than

defensively. Yamamoto hoped, but probably did not believe, if the

Americans could be dealt such terrific blows early in the war, they

might be willing to negotiate an end to the conflict. As it turned out,

however, the note officially breaking diplomatic relations with the

United States was delivered late, and he correctly perceived the

Americans would be resolved upon revenge and unwilling to negotiate. The

Naval General Staff proved reluctant to go along and Yamamoto was

eventually driven to capitalize on his popularity in the fleet by

threatening to resign to get his way. Admiral Osami Nagano and the Naval General Staff eventually caved in to this pressure, but only insofar as approving the attack on Pearl Harbor. The

First Air Fleet commenced preparations for the Pearl Harbor Raid,

solving a number of technical problems along the way, including how to

launch torpedoes in the shallow water of Pearl Harbor and how to craft

armor-piercing bombs by machining down battleship gun projectiles. As Yamamoto had planned, the First Air Fleet of six carriers armed with about 390 planes, commenced hostilities against the Americans on 7 December 1941, launching 353 aircraft

against Pearl Harbor in two waves. The attack was a complete success

according to the parameters of the mission which sought to sink at

least four American battleships and prevent the U.S. Fleet from

interfering in Japan's southward advance for at least six months.

American aircraft carriers were also considered a choice target, but

were not in port at the time of the attack. In the end, five American battleships were sunk, three damaged, and eleven other cruisers, destroyers and

auxiliaries were sunk or seriously damaged. The Japanese lost only 29

aircraft, but suffered damage to more than 111 aircraft. The damaged

aircraft were disproportionately dive and torpedo bombers,

seriously impacting available firepower to exploit the first two waves'

success, so the commander of the First Air Fleet, Naval

Lieutenant-General Chuichi Nagumo,

withdrew. Yamamoto later lamented Nagumo's failure to seize the

initiative to seek out and destroy the American carriers, absent from

the harbor, or further bombard various strategically important

facilities on Oahu. With

the American Fleet largely neutralized at Pearl Harbor, Yamamoto's

Combined Fleet turned to the task of executing the larger Japanese war

plan devised by the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy General Staff. The First Air Fleet proceeded to make a circuit of the Pacific, striking American, Australian, Dutch and British installations from Wake Island to Australia to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) in the Indian Ocean.

The 11th Air Fleet caught the American 5th Air Force on the ground in

the Philippines hours after Pearl Harbor, and then proceeded to sink

the British Force "Z" (battleship HMS Prince of Wales and battlecruiser HMS Repulse) underway at sea. Competing plans were developed at this stage. In the midst of these debates, the Doolittle Raid struck Tokyo and

the surrounding areas, galvanizing the threat posed by the American

aircraft carriers in the minds of staff officers, and giving Yamamoto

an event he could exploit to get his way. The Naval General Staff

agreed to Yamamoto's Midway (MI) Operation, subsequent to the first

phase of the operations against Australia's link with America, and

concurrent with their own plan to seize positions in the Aleutian Islands. Yamamoto's

plan for Midway Island was an extension of his efforts to knock the

U.S. Pacific Fleet out of action long enough for Japan to fortify her

defensive perimeter in the Pacific island chains. Yamamoto felt it

necessary to seek an early, offensive decisive battle. While

Fifth Fleet attacked the Aleutians, First Mobile Force (4 carriers, 2

battleships, 3 cruisers, and 12 destroyers) would raid Midway and

destroy its air force. Once this was neutralized, Second Fleet (1 light

carrier, 2 battleships, 10 cruisers, 21 destroyers, and 11 transports)

would land 5,000 troops to seize the atoll from the American Marines. The

seizure of Midway was expected to draw the American carriers west into

a trap where the First Mobile Force would engage and destroy them.

Afterward, First Fleet (1 light carrier, 7 battleships, 3 cruisers and

13 destroyers), in conjunction with elements of Second Fleet, would mop

up remaining American surface forces and complete the destruction of

the Pacific Fleet. To

guard against mischance, Yamamoto initiated two security measures. The

first was an aerial reconnaissance mission (Operation K) over Pearl

Harbor to ascertain if the American carriers were there. The second was

a picket line of submarines to detect the movement of the American

carriers toward Midway in time for First Mobile Force, First Fleet, and

Second Fleet to combine against it. In the event, the first was aborted

and the second delayed until after American carriers had sortied. The plan was a compromise and hastily prepared (apparently so it could be launched in time for the anniversary of Tsushima), but

appeared well thought out, well organized, and finely timed when viewed

from a Japanese viewpoint. Against four carriers, two light carriers,

11 battleships, 16 cruisers and 46 destroyers likely to be in the area

of the main battle the Americans could field only three carriers, eight

cruisers, and 15 destroyers. The disparity appeared crushing. Only in

numbers of carrier decks, available aircraft, and submarines was there

near parity between the two sides. Despite various frictions developed

in the execution, it appeared — barring something extraordinary —

Yamamoto held all the cards. Unfortunately

for Yamamoto, something extraordinary had happened. The worst fear of

any commander is for an enemy to learn his battle plan in advance,

which was exactly what American cryptographers had done, thanks to breaking the Japanese naval code D (known to the U.S. as JN-25). As a result, Admiral Chester Nimitz,

the Pacific Fleet commander, was able to circumvent both of Yamamoto's

security measures and position his outnumbered forces in the exact

position to conduct a devastating ambush. By Nimitz's calculation, his

three available carrier decks, plus Midway, gave him rough parity with

Nagumo's First Mobile Force. Following a foolish nuisance raid by Japanese flying boats in May, Nimitz dispatched a minesweeper to guard the intended refueling point for

Operation K, causing the reconnaissance mission to be aborted and

leaving Yamamoto ignorant of whether Pacific Fleet carriers were still

at Pearl Harbor. (It remains unclear why Yamamoto permitted the early

flight, when pre-attack reconnaissance was essential to the success of

MI.) He also dispatched his carriers toward Midway early, and they

passed the intended picket line force of submarines en route to

their station, negating Yamamoto's back-up security measure. Nimitz's

carriers then positioned themselves to ambush the First Mobile Force

when it struck Midway. A token cruiser and destroyer force was

dispatched toward the Aleutians, but otherwise ignored it. Days before

Yamamoto expected American carriers to interfere in the Midway

operation, they destroyed the four carriers of the First Mobile Force

on 4 June 1942, catching the Japanese carriers at precisely their most

vulnerable moment. With

his air power destroyed and his forces not yet concentrated for a fleet

battle, Yamamoto attempted to maneuver his remaining forces, still

strong on paper, to trap the American forces. He was unable to do so

because his initial dispositions had placed his surface combatants too

far from Midway, and because Admiral Raymond Spruance prudently withdrew to the east in a position to further defend Midway Island, believing (based on a mistaken submarine report) the Japanese still intended to invade. Not knowing that several battleships including the extremely powerful Yamato were on the Japanese order of battle,

he did not comprehend the severe risk of a night surface battle, in

which his carriers and cruisers would be at a disadvantage. However,

his move to the east did avoid the possibility of such a battle taking

place. Correctly perceiving that he had lost, Yamamoto aborted the

invasion of Midway and withdrew. The defeat ended Yamamoto's six months

of success and marked the high tide of Japanese expansion. The

Battle of Midway solidly checked Japanese momentum, but the IJN was

still a powerful force and capable of regaining the initiative. They

planned to resume the thrust with Operation FS aimed at eventually taking Samoa and Fiji to cut the American life-line to Australia. This was expected to short-circuit the threat posed by General Douglas MacArthur and his American and Australian forces in New Guinea. To this end, development of the airfield on Guadalcanal continued and attracted the baleful eye of Yamamoto's opposite number, Admiral Ernest King. King

ramrodded the idea of an immediate American counterattack to prevent

the Japanese from regaining the initiative through the Joint Chiefs of

Staff. This precipitated the American invasion of Guadalcanal and beat

the Japanese to the punch, with Marines landing on the island in August

1942 and starting a bitter struggle that lasted until February 1943 and

commenced a battle of attrition Japan could ill afford. Yamamoto

remained in command, retained at least partly to avoid diminishing the

morale of the Combined Fleet. However, he had lost face in the Midway

defeat and the Naval General Staff were disinclined to indulge further

gambles. This reduced Yamamoto to pursuing the classic defensive

Decisive Battle strategy he had attempted to overturn. Guadalcanal

caught the Japanese over-extended and attempting to support fighting in

New Guinea while guarding the Central Pacific and preparing to conduct

Operation FS. The FS operation was abandoned and the Japanese attempted

to fight in both New Guinea and Guadalcanal at the same time. Already

stretched thin, they suffered repeated setbacks due to a lack of

shipping, a lack of troops, and a disastrous inability to coordinate

Army and Navy activities. Yamamoto

committed Combined Fleet units to a series of small attrition actions

that stung the Americans, but suffered losses he could ill afford in

return. Three major efforts to carry the island precipitated a pair of

carrier battles that Yamamoto commanded personally at the Eastern Solomons and Santa Cruz Islands in September and October, and finally a wild pair of surface engagements in

November, all timed to coincide with Japanese Army pushes. The timing

of each major battle was successively derailed when the army could not

hold up its end of the operation. Yamamoto's forces caused considerable

losses and damage, but he could never draw the Americans into a

decisive fleet action. As a result, the Japanese Navy's strength began

to bleed off. There

were severe losses of carrier dive-bomber and torpedo-bomber crews in

the carrier battles, emasculating the already depleted carrier air

groups. Japan could not hope to match the United States in quantities

of well-trained replacement pilots, and the quality of both Japanese

land-based and naval aviation began declining. Particularly harmful,

however, were losses of destroyers in the foolish Tokyo Express supply runs. The IJN already faced a shortage of such ships, and these losses further exacerbated Japan's already weakened commerce defense. With

Guadalcanal lost in February 1943, there was no further attempt to seek

a major battle in the Solomon Islands although smaller attrition

battles continued. Yamamoto shifted the load of the air battle from the

depleted carriers to the land-based naval air forces. To boost morale

following the defeat at Guadalcanal, Yamamoto decided to make an

inspection tour throughout the South Pacific. On 14 April 1943, the US naval intelligence effort, code-named "Magic",

intercepted and decrypted a message containing specific details

regarding Yamamoto's tour, including arrival and departure times and

locations, as well as the number and types of planes that would

transport and accompany him on the journey. Yamamoto, the itinerary

revealed, would be flying from Rabaul to Ballalae Airfield, on an island near Bougainville in the Solomon Islands, on the morning of 18 April 1943. U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox to "Get Yamamoto." Knox instructed Admiral Chester W. Nimitz of Roosevelt's wishes. Admiral Nimitz consulted Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., Commander, South Pacific, then authorized a mission on 17 April to intercept Yamamoto's flight en route and shoot it down. A squadron of P-38 Lightning aircraft

were assigned the task as only they possessed the range to intercept

and engage. Eighteen hand-picked pilots from three units were informed

that they were intercepting an "important high officer" with no

specific name given. On the morning of 18 April, despite urgings by

local commanders to cancel the trip for fear of ambush, Yamamoto's two Mitsubishi G4M fast transport aircraft left Rabaul as scheduled for the 315 mi (507 km) trip. Shortly after, 18 P-38s with long-range drop tanks took

off from Guadalcanal. Sixteen arrived after wave-hopping most of the

430 mi (690 km) to the rendezvous point, maintaining radio

silence throughout. At 09:34 Tokyo time, the two flights met and a

dogfight ensued between the P-38s and the six escorting A6M Zeroes. First Lieutenant Rex T. Barber engaged the first of the two Japanese transports which turned out to be Yamamoto's plane.

He targeted the aircraft with gunfire until it began to spew smoke from

its left engine. Barber turned away to attack the other transport as

Yamamoto's plane crashed into the jungle. The

crash site and body of Yamamoto were found the next day in the jungle

north of the then-coastal site of the former Australian patrol post of Buin by

a Japanese search and rescue party, led by army engineer, Lieutenant

Hamasuna. According to Hamasuna, Yamamoto had been thrown clear of the

plane's wreckage, his white-gloved hand grasping the hilt of his katana,

still upright in his seat under a tree. Hamasuna said Yamamoto was

instantly recognizable, head dipped down as if deep in thought. A post-mortem of

the body disclosed that Yamamoto had received two gunshot wounds, one

to the back of his left shoulder and another to his left lower jaw that

exited above his right eye. Despite the evidence, the question of

whether or not he initially survived the crash has been a matter of

controversy in Japan. To cover up the fact that the Allies were reading Japanese code, American news agencies were told that civilian coast-watchers in

the Solomon Islands saw Yamamoto boarding a bomber in the area. They

did not publicize the names of most of the pilots that attacked

Yamamoto's plane because one of them had a brother who was a prisoner

of the Japanese, and U.S. military officials feared for his safety.

Under Yamamoto's able subordinates, Naval Lieutenant-Generals Jisaburo Ozawa, Nobutake Kondo and Ibo Takahashi,

the Japanese swept the inadequate remaining American, British, Dutch

and Australian naval assets from the Netherlands East Indies in a

series of amphibious landings and surface naval battles that culminated

in the Battle of the Java Sea on

27 February 1942. With the occupation of the Netherlands East Indies,

and the reduction of the remaining American positions in the

Philippines to forlorn hopes on the Bataan Peninsula and Corregidor island, the Japanese had secured their oil- and rubber-rich "Southern Resources Area". Having

achieved their initial aims with surprising speed and little loss

(albeit against enemies ill-prepared to resist them), the Japanese

paused to consider their next moves. Since neither the British nor the

Americans were willing to negotiate, their thoughts turned to securing

and protecting their newly seized territory, and acquiring more with an

eye toward additional conquest and/or attempting to force one or more

of their enemies out of the war.

Yamamoto rushed planning for the Midway and Aleutians missions, while dispatching a force under Naval Major-General Takeo Takagi, including the Fifth Carrier Division (the large, new carriers Shōkaku and Zuikaku), to support the effort to seize the islands of Tulagi and Guadalcanal for seaplane and airplane bases, and the town of Port Moresby on Papua New Guinea's south coast facing Australia. The Port Moresby (MO) Operation proved

an unwelcome reverse. Although Tulagi and Guadalcanal were taken, the

Port Moresby invasion fleet was compelled to turn back when Takagi

clashed with an American carrier task force in the Battle of the Coral Sea in early May. Although the Japanese sank the American carrier USS Lexington in exchange for a smaller carrier, the Americans damaged the carrier Shōkaku so

badly that she required dockyard repairs. Just as importantly, Japanese

operational mishaps and American fighters and anti-aircraft fire

devastated the dive bomber and torpedo plane elements of both Shōkaku's and Zuikaku's air groups. These losses sidelined Zuikaku while

she awaited replacement aircraft and aircrews, and saw to tactical

integration and training. These two ships would be sorely missed a

month later at Midway.