<Back to Index>

- Molecular Biologist James Dewey Watson, 1928

- Painter and Architect Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, 1483

- Chancellor of Germany Kurt Georg Kiesinger, 1904

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (April 6 or March 28, 1483 – April 6, 1520), better known simply as Raphael, was an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance, celebrated for the perfection and grace of his paintings and drawings. Together with Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, he forms the traditional trinity of great masters of that period.

Raphael

was enormously productive, running an unusually large workshop, and

despite his death at thirty-seven, a large body of his work remains.

Many of his works are found in the Apostolic Palace of The Vatican, where the frescoed Raphael Rooms were

the central, and the largest, work of his career. After his early years

in Rome, much of his work was designed by him and executed largely by

the workshop from his drawings, with considerable loss of quality. He

was extremely influential in his lifetime, though outside Rome his work

was mostly known from his collaborative printmaking.

After his death, the influence of his great rival Michelangelo was more

widespread until the 18th and 19th centuries, when Raphael's more

serene and harmonious qualities were again regarded as the highest

models. His career falls naturally into three phases and three styles, first described by Giorgio Vasari: his early years in Umbria, then a period of about four years (from 1504–1508) absorbing the artistic traditions of Florence, followed by his last hectic and triumphant twelve years in Rome, working for two Popes and their close associates. Raphael was born in the small but artistically significant Central Italian city of Urbino in the Marche region, where his father Giovanni Santi was court painter to the Duke. The reputation of the court had been established by Federico III da Montefeltro, a highly successful condottiere who had been created Duke of Urbino by the Pope - Urbino formed part of the Papal States -

and who died the year before Raphael was born. The emphasis of

Federico's court was rather more literary than artistic, but Giovanni

Santi was a poet of sorts as well as a painter, and had written a

rhymed chronicle of the life of Federico, and both wrote the texts and

produced the decor for masque-like

court entertainments. Federico was succeeded by his son Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, who married Elisabetta Gonzaga, daughter of the ruler of Mantua,

the most brilliant of the smaller Italian courts for both music and the

visual arts. Under them, the court continued as a centre for literary

culture. Growing up in the circle of this small court gave Raphael the

excellent manners and social skills stressed by Vasari. Court life in Urbino at just after this period was to become set as the model of the virtues of the Italian humanist court by Baldassare Castiglione's depiction of it in his classic work The Book of the Courtier,

published in 1528. Castiglione moved to Urbino in 1504, when Raphael

was no longer based there but frequently visited, and they became good

friends. Other regular visitors to the court were also to become great

friends: Pietro Bibbiena and Pietro Bembo, both later Cardinals,

were already becoming well known as writers, and would be in Rome

during Raphael's period there. Raphael mixed easily in the highest

circles throughout his life, one of the factors that tended to give a

misleading impression of effortlessness to his career. He did not

receive a full humanistic education however; it is unclear how easily he read Latin. His

mother Màgia died in 1491 when Raphael was eight, followed on

August 1, 1494 by his father, who had already remarried. Orphaned at

eleven, Raphael's formal guardian became his only paternal uncle

Bartolomeo, a priest, who subsequently engaged in litigation with his

stepmother. He probably continued to live with his stepmother when not

living as an apprentice with a master. He had already shown talent, according to Giorgio Vasari, who tells that Raphael had been "a great help to his father". A brilliant self-portrait drawing from his teenage years shows his precocious talent. His

father's workshop continued and, probably together with his stepmother,

Raphael evidently played a part in managing it from a very early age.

In Urbino, he came into contact with the works of Paolo Uccello, previously the court painter (d. 1475), and Luca Signorelli, who until 1498 was based in nearby Città di Castello. His father placed him in the workshop of the Umbrian master Pietro Perugino as an apprentice "despite the tears of his mother". An alternative theory is that he received at least some training

from Timoteo Viti, who acted as court painter in Urbino from 1495. But

most modern historians agree that Raphael at least worked as an

assistant to Perugino from around 1500; the influence of Perugino on

Raphael's early work is very clear: Apart from stylistic closeness, their techniques are

very similar as well, for example having paint applied thickly, using

an oil varnish medium, in shadows and darker garments, but very thinly

on flesh areas. An excess of resin in the varnish often causes cracking

of areas of paint in the works of both masters. The Perugino workshop was active in both Perugia and Florence, perhaps maintaining two permanent branches. Raphael is described as a "master", that is to say fully trained, in 1501. His first documented work was the Baronci altarpiece for the church of Saint Nicholas of Tolentino in

Città di Castello, a town halfway between Perugia and Urbino.

Evangelista da Pian di Meleto, who had worked for his father, was also

named in the commission. It was commissioned in 1500 and finished in

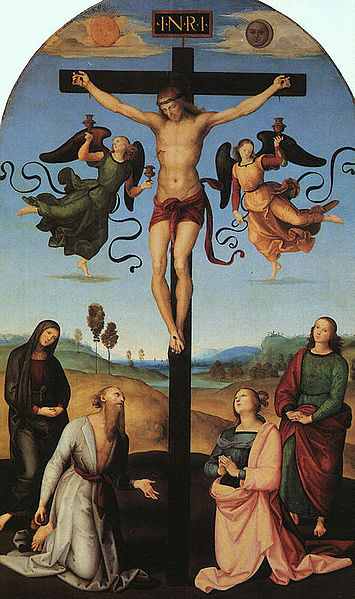

1501; now only some cut sections and a preparatory drawing remain. In the following years he painted works for other churches there, including the "Mond Crucifixion" (about 1503) and the Brera Wedding of the Virgin (1504), and for Perugia, such as the Oddi Altarpiece. He very probably also visited Florence in this period. These are large works, some in fresco,

where Raphael confidently marshalls his compositions in the somewhat

static style of Perugino. He also painted many small and exquisite cabinet paintings in these years, probably mostly for the connoisseurs in the Urbino court, like the Three Graces and St. Michael, and he began to paint Madonnas and portraits. In 1502 he went to Siena at the invitation of another pupil of Perugino, Pinturicchio, "being a friend of Raphael and knowing him to be a draughtsman of the highest quality" to help with the cartoons, and very likely the designs, for a fresco series in the Piccolomini Library in Siena Cathedral. He was evidently already much in demand even at this early stage in his career. Raphael

led a "nomadic" life, working in various centres in Northern Italy, but

spent a good deal of time in Florence, perhaps from about 1504.

However, although there is traditional reference to a "Florentine

period" of about 1504-8, he was possibly never a continuous resident

there. He

may have needed to visit the city to secure materials in any case.

There is a letter of recommendation of Raphael, dated October 1504,

from the mother of the next Duke of Urbino to the Gonfaloniere of Florence:

"The bearer of this will be found to be Raphael, painter of Urbino,

who, being greatly gifted in his profession has determined to spend

some time in Florence to study. And because his father was most worthy

and I was very attached to him, and the son is a sensible and

well-mannered young man, on both accounts, I bear him great love...". As

earlier with Perugino and others, Raphael was able to assimilate the

influence of Florentine art, whilst keeping his own developing style.

Frescos in Perugia of about 1505 show a new monumental quality in the

figures which may represent the influence of Fra Bartolomeo, who was a friend of Raphael. But the most striking influence in the work of these years is Leonardo da Vinci,

who returned to the city from 1500 to 1506. Raphael's figures begin to

take more dynamic and complex positions, and though as yet his painted

subjects are still mostly tranquil, he made drawn studies of fighting

nude men, one of the obsessions of the period in Florence. Another

drawing is a portrait of a young woman that uses the three-quarter

length pyramidal composition of the just-completed "Mona Lisa", but still looks completely Raphaelesque. Another of Leonardo's compositional inventions, the pyramidal Holy Family, was repeated in a series of works that remain among his most famous easel paintings. There is a drawing by Raphael in the Royal Collection of Leonardo's lost Leda and the Swan, from which he adapted the contrapposto pose of his own Saint Catherine of Alexandria. He also perfects his own version of Leonardo's sfumato modelling,

to give subtlety to his painting of flesh, and develops the interplay

of glances between his groups, which are much less enigmatic than those

of Leonardo. But he keeps the soft clear light of Perugino in his

paintings. Leonardo

was more than thirty years older than Raphael, but Michelangelo, who

was in Rome for this period, was just eight years his senior.

Michelangelo already disliked Leonardo, and in Rome came to dislike

Raphael even more, attributing conspiracies against him to the younger

man. Raphael

would have been aware of his works in Florence, but in his most

original work of these years, he strikes out in a different direction. By the end of 1508, he had moved to Rome, where he lived for the rest of his life. He was invited by the new Pope Julius II, perhaps at the suggestion of his architect Donato Bramante, then engaged on St. Peter's, who came from just outside Urbino and was distantly related to Raphael. Unlike Michelangelo, who had been kept hanging around in Rome for several months after his first summons, Raphael was immediately commissioned by Julius to fresco what was intended to become the Pope's private library at the Vatican Palace. This

was a much larger and more important commission than any he had

received before; he had only painted one altarpiece in Florence itself.

Several other artists and their teams of assistants were already at

work on different rooms, many painting over recently completed

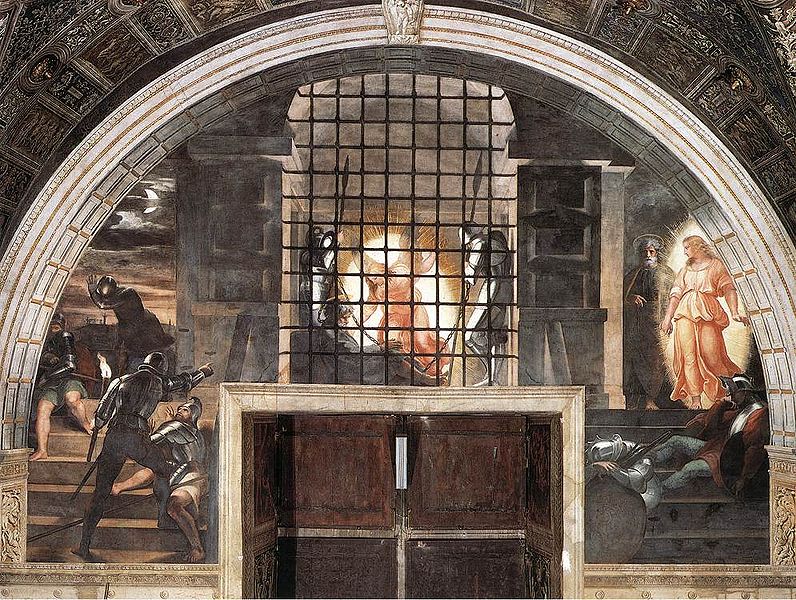

paintings commissioned by Julius's loathed predecessor, Alexander VI, whose contributions, and arms, Julius was determined to efface from the palace. Michelangelo, meanwhile, had been commissioned to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling. This first of the famous "Stanze" or "Raphael Rooms" to be painted, now always known as the Stanza della Segnatura, was to make a stunning impact on Roman art,

and remains generally regarded as his greatest masterpiece, containing The School of Athens, The Parnassus and the Disputa.

Raphael was then given further rooms to paint, displacing other artists

including Perugino and Signorelli. He completed a sequence of three

rooms, each with paintings on each wall and often the ceilings too,

increasingly leaving the work of painting from his detailed drawings to

the large and skilled workshop team he had acquired, who added a fourth

room, probably only including some elements designed by Raphael, after

his early death in 1520. The death of Julius in 1513 did not interrupt

the work at all, as he was succeeded by Raphael's last Pope, the Medici Pope Leo X, with whom Raphael formed an even closer relationship, and who continued to commission him. Raphael's friend Cardinal Bibbiena was also one of Leo's old tutors, and a close friend and advisor. Raphael

was clearly influenced by Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling in the

course of painting the room. Bramante let him in secretly,

and the scaffolding was taken down in 1511 from the first completed

section. The reaction of other artists to the daunting force of

Michelangelo was the dominating question in Italian art for the

following few decades, and Raphael, who had already shown his gift for

absorbing influences into his own personal style, rose to the challenge

perhaps better than any other artist. One of the first and clearest

instances was the portrait in The School of Athens of Michelangelo himself, as Heraclitus, which seems to draw clearly from the Sybils and ignudi of

the Sistine ceiling. Other figures in that and later paintings in the

room show the same influences, but as still cohesive with a development

of Raphael's own style. Michelangelo

accused Raphael of plagiarism and years after Raphael's death,

complained in a letter that "everything he knew about art he got from

me", although other quotations show more generous reactions. The

Vatican projects took most of his time, although he painted several

portraits, including those of his two main patrons, the popes Julius II and his successor Leo X,

the former considered one of his finest. Other portraits were of his

own friends, like Castiglione, or the immediate Papal circle. Other

rulers pressed for work, and King Francis I of France was sent two paintings as diplomatic gifts from the Pope. For Agostino Chigi, the hugely rich banker and Papal Treasurer, he painted the Galatea and designed further decorative frescoes for his Villa Farnesina, and painted two chapels in the churches of Santa Maria della Pace and Santa Maria del Popolo. He also designed some of the decoration for the Villa Madama, the work in both villas being executed by his workshop. One of his most important papal commissions was the Raphael Cartoons (now Victoria and Albert Museum), a series of 10 cartoons, of which seven survive, for tapestries with scenes of the lives of Saint Paul and Saint Peter, for the Sistine Chapel. The cartoons were sent to Brussels to be woven in the workshop of Pier van Aelst. It is possible that Raphael saw the finished series before his death—they were probably completed in 1520. He also designed and painted the Loggia at the Vatican, a long thin gallery then open to a courtyard on one side, decorated with Roman-style grottesche. He produced a number of significant altarpieces, including The Ecstasy of St. Cecilia and the Sistine Madonna. His last work, on which he was working up to his death, was a large Transfiguration, which together with Il Spasimo shows the direction his art was taking in his final years—more proto-Baroque than Mannerist. Raphael eventually had a workshop of fifty pupils and

assistants, many of whom later became significant artists in their own

right. This was arguably the largest workshop team assembled under any

single old master painter,

and much higher than the norm. They included established masters from

other parts of Italy, probably working with their own teams as

sub-contractors, as well as pupils and journeymen. We have very little

evidence of the internal working arrangements of the workshop, apart

from the works of art themselves, often very difficult to assign to a

particular hand. The most important figures were Giulio Romano, a young pupil from Rome (only about twenty-one at Raphael's death), and Gianfrancesco Penni,

already a Florentine master. They were left many of Raphael's drawings

and other possessions, and to some extent continued the workshop after

Raphael's death. Penni did not achieve a personal reputation equal to

Giulio's, as after Raphael's death he became Giulio's less-than-equal

collaborator in turn for much of his subsequent career. Perino del Vaga, already a master, and Polidoro da Caravaggio,

who was supposedly promoted from a labourer carrying building materials

on the site, also became notable painters in their own right.

Polidoro's partner, Maturino da Firenze, has, like Penni, been overshadowed in subsequent reputation by his partner. Giovanni da Udine had a more independent status, and was responsible for the decorative stucco work and grotesques surrounding the main frescoes. Most of the artists were later scattered, and some killed, by the violent Sack of Rome in 1527. This

did however contribute to the diffusion of versions of Raphael's style

around Italy and beyond. Raphael ran a very harmonious and efficient

workshop,

and had extraordinary skill in smoothing over troubles and arguments

with both patrons and his assistants - a contrast with the stormy

pattern of Michelangelo's relationships with both. In

1515 he was given powers as "Prefect" over all antiquities unearthed

entrusted within the city, or a mile outside. Raphael wrote a letter to

Pope Leo suggesting ways of halting the destruction of ancient

monuments, and proposed a visual survey of the city to record all

antiquities in an organised fashion. The Pope's concerns were not

exactly the same; he intended to continue to re-use ancient masonry in

the building of St Peter's, but wanted to ensure that all ancient

inscriptions were recorded, and sculpture preserved, before allowing

the stones to be reused. Raphael made no prints himself, but entered into a collaboration with Marcantonio Raimondi to produce engravings to Raphael's designs, which created many of the most famous Italian prints of the century, and was important in the rise of the reproductive print. His interest was unusual in such a major artist; from his contemporaries only Titian, who had worked much less successfully with Raimondi, shared it. A

total of about fifty prints were made; some were copies of Raphael's

paintings, but other designs were apparently created by Raphael purely

to be turned into prints. Raphael made preparatory drawings, many of

which survive, for Raimondi to translate into engraving. The most famous original prints to result from the collaboration were Lucretia, the Judgement of Paris and The Massacre of the Innocents. Among prints of the paintings The Parnassus and Galatea were

also especially well-known. Outside Italy, reproductive prints by

Raimondi and others were the main way that Raphael's art was

experienced until the twentieth century. Baviero Carocci, an assistant who Raphael evidently trusted with his money, ended

up in control of most of the copper plates after Raphael's death, and

had a successful career in the new occupation of a publisher of prints. Raphael

lived in the Borgo, in rather grand style in a palace designed by

Bramante. He never married, but in 1514 became engaged to Maria

Bibbiena, Cardinal Medici Bibbiena's niece; he seems to have been

talked into this by his friend the Cardinal, and his lack of enthusiasm

seems to be shown by the marriage not taking place before she died in

1520. He

is said to have had many affairs, but a permanent fixture in his life

in Rome was "La Fornarina", Margherita Luti, the daughter of a baker (fornaro) named Francesco Luti from Siena who lived at Via del Governo Vecchio. He was made a "Groom of the Chamber" of the Pope, which gave him status at court and an additional income, and also a knight of the Papal Order of the Golden Spur. Raphael's premature death on Good Friday (April

6, 1520) (possibly his 37th birthday), was allegedly caused by a night of

excessive sex with Luti, after which he fell into a fever and, not

telling his doctors that this was its cause, was given the wrong cure,

which killed him. Whatever the cause, in his acute illness, which lasted fifteen days, Raphael was composed enough to receive the last rites,

and to put his affairs in order. He dictated his will, in which he left

sufficient funds for his mistress's care, entrusted to his loyal

servant Baviera, and left most of his studio contents to Giulio Romano

and Penni. At his request, Raphael was buried in the Pantheon. His funeral was extremely grand, attended by large crowds. The inscription in his marble sarcophagus, an elegiac distich written by Pietro Bembo,

reads: "Ille hic est Raffael, timuit quo sospite vinci, rerum magna

parens et moriente mori." Meaning: "Here lies that famous Raphael by

whom Nature feared to be conquered while he lived, and when he was

dying, feared herself to die."

After Bramante's death in 1514, he was named architect of the new St Peter's.

Most of his work there was altered or demolished after his death and

the acceptance of Michelangelo's design, but a few drawings have

survived. It appears his designs would have made the church a good deal

gloomier than the final design, with massive piers all the way down the

nave. It would perhaps have resembled the temple in the background of the The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple. He

designed several other buildings, and for a short time was the most

important architect in Rome, working for a small circle around the

Papacy. Julius had made changes to the street plan of Rome, creating

several new thoroughfares, and he wanted them filled with splendid

palaces. An important building, the Palazzo Aquila for Leo's Papal Chamberlain, was completely destroyed to make way for Bernini's piazza for

St. Peter's, but drawings of the facade and courtyard remain. The main designs for the Villa Farnesina were not by Raphael, but he did design, and paint, the Chigi Chapel for the same patron, Agostino Chigi, the Papal Treasurer. Another building, for Pope Leo's doctor, the Palazzo di Jacobo da Brescia,

was moved in the 1930s but survives; this was designed to complement a

palace on the same street by Bramante, where Raphael himself lived for

a time. The Villa Madama, a lavish hillside retreat for Cardinal Giulio de' Medici, later Pope Clement VII,

was never finished, and his full plans have to be reconstructed

speculatively. He produced a design from which the final construction

plans were completed by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger. Only some floor-plans remain for a large palace planned for himself on the new "Via Giulia" in the Borgo,

for which he was accumulating the land in his last years. It was on an

irregular island block near the river Tiber.