<Back to Index>

- Engineer Charles Proteus Steinmetz, 1865

- Poet Charles Pierre Baudelaire, 1821

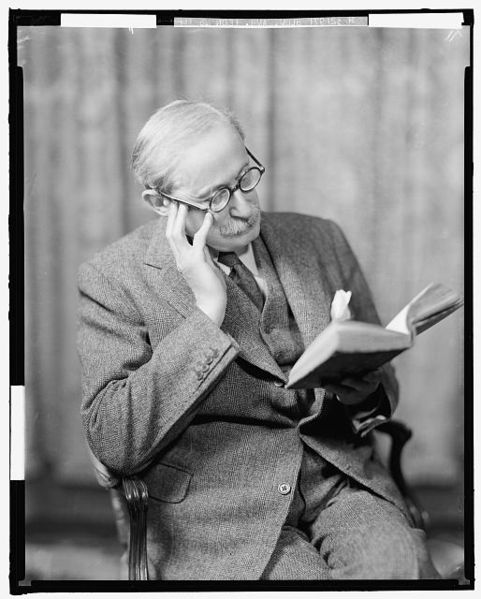

- Prime Minister of France André Léon Blum, 1872

André Léon Blum (9 April 1872 – 30 March 1950) was a French politician, usually identified with the moderate left, and three times the Prime Minister of France.

Blum was born in the Paris Jewish community: he attended the Lycée Henri IV. There he met the writer André Gide and published his first poems at the age of 17 in a journal they created. Blum entered the prestigious École Normale Supérieure in 1890. After graduation, he wavered between studying law and literature. Rather than choose between them, he decided to study both at the Sorbonne, graduating in literature in 1890 and in law in 1894. He then worked as a government lawyer while developing a second career as a literary critic, in particular as an authority on Goethe. He soon became one of France's leading literary figures. While in his youth an avid reader of the works of the nationalist writer Maurice Barrès, Blum had little interest in politics until the Dreyfus Affair of 1894, which had a traumatic effect on him as it did on many French Jews. Campaigning as a Dreyfusard brought him into contact with the socialist leader Jean Jaurès, whom he greatly admired. He began contributing to the socialist daily, L'Humanité, and joined the Socialist Party, then called the SFIO. Soon he was the party's main theoretician.

In July 1914, just as the First World War broke out, Jaurès was assassinated, and Blum became more active in the Socialist party leadership. In 1919 he was chosen as chair of the party's executive committee, and was also elected to the National Assembly as a representative of Paris. Believing that there was no such thing as a "good dictatorship", he opposed participation in the Comintern. Therefore, in 1920, he worked to prevent a split between supporters and opponents of the Russian Revolution, but the radicals seceded, taking L'Humanité with them, and formed the SFIC. Blum led the SFIO through the 1920s and 1930s, and was also editor of the party's new paper, Le Populaire. Blum was elected as Deputy for Narbonne in 1929, and was re-elected in 1932 and 1936. In 1933, he expelled Marcel Déat, Pierre Renaudel, and other neosocialists from the SFIO. Political circumstances changed in 1934, when the rise of German dictator Adolf Hitler and fascist riots in Paris caused Stalin and the French Communists to change their policy. In 1935 all the parties of left and centre formed the Popular Front, which at the elections of June 1936 won a sweeping victory. On 13 February 1936, shortly before becoming Prime Minister, Blum was dragged from a car and almost beaten to death by the Camelots du Roi,

a group of anti-Semites and royalists. The right-wing Action

Française league was dissolved by the government following this

incident, not long before the elections that brought Blum to power. Blum became the first socialist and the first Jew to serve as Prime Minister of France. As such he was an object of particular hatred to the Catholic and anti-Semitic right, and was denounced in the National Assembly by Xavier Vallat, a right-wing Deputy and sympathizer of the Action Française (later Commissioner for Jewish Affairs in the Vichy wartime government). The

industrial workers responded to the election of the Popular Front

government by occupying their factories, confident that "the

revolution" was imminent. For Blum, as a Marxist, this was an agonising

moment. He did not believe that socialism could be achieved by

parliamentary means. But he could not encourage the workers to launch

an attempt at a revolution: he believed that the army would intervene

and the workers would be massacred as they had been at the Paris Commune in 1871. He persuaded the workers to accept pay raises and go back to work. Similarly, when the Spanish Civil War broke

out, Blum was forced to adopt a policy of neutrality rather than assist

his ideological fellows, the Spanish socialists, for fear of splitting

his alliance with the centrist Radicals, or even precipitating a civil

war in France. But this policy strained his alliance with the

Communists, who followed Soviet policy and urged all out support for the Spanish Republic.

The impossible dilemma caused by this issue led Blum to resign in June

1937. He was briefly Prime Minister again in March and April 1938, but

was unable to establish a stable ministry. Despite

its short life, the Popular Front government passed much important

legislation, including the 40-hour week, paid holidays for the workers,

collective bargaining on wage claims and the nationalisation of the arms industry. Blum also passed legislation extending the rights of the Arab population of Algeria. In foreign policy, his government was divided between the traditional anti-militarism of the French left and the urgency of the rising threat of Nazi Germany. Despite the division, the government managed to engage the greatest war effort since the First World War. When

the Germans occupied France in June 1940, Blum made no effort to leave

the country, despite the extreme danger he was in as a Jew and a

socialist leader. He was among "The Vichy 80", a minority of parliamentarians that refused to grant full powers to Marshal Philippe Pétain. He was arrested by the authorities in September and held until 1942, when he was put on trial in the Riom Trial on

charges of treason, for having "weakened France's defences". He used

the courtroom to make a brilliant indictment of the French military and

pro-German politicians like Pierre Laval.

The trial was such an embarrassment to the Vichy regime that the

Germans ordered it called off. In April 1943, the Germans deported Blum

to Germany, where he was imprisoned in Buchenwald until

April 1945. He was imprisoned in the section reserved for high-ranking

prisoners. His future wife, Janot Blum, chose to come to the camp

voluntarily to live with him inside the camp. The Blums were the only

Jews to have married inside the concentration camp system. While the

Blum family was at Buchenwald, they did not know about the atrocities

until the Americans bombed the factories. As the Allied armies approached Buchenwald, he was transferred to Dachau, near Munich, and in late April 1945, together with other notable inmates, to Tyrol. In the last weeks of the war the Nazi regime

gave orders that he was to be executed, but the local authorities

decided not to obey them. Blum was rescued by Allied troops in May

1945. While in prison he wrote his best known work, the essay À l'échelle Humaine ("For all mankind"). His brother René, the founder of the Ballet de l'Opéra à Monte Carlo, was deported to Auschwitz and murdered.

After

the war, Léon Blum returned to politics, and was again briefly

Prime Minister in the transitional postwar coalition government. He

advocated the alliance between the center-left and the center-right

parties in order to support the Fourth Republic against

the Gaullists and the Communists. He also served as an ambassador on a

government loan mission to the United States, and as head of the French

mission to UNESCO. He continued to write for Le Populaire until his death at Jouy-en-Josas, near Paris, on 30 March 1950. The kibbutz of Kfar Blum in northern Israel is named after him.