<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Sir Andrew John Wiles, 1953

- Sculptor Gustav Vigeland, 1869

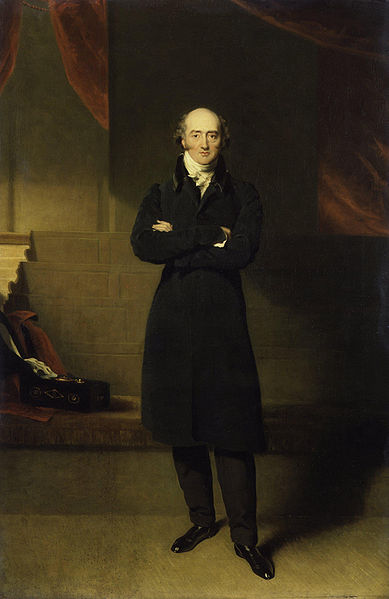

- Prime Minister of the United Kingdom George Canning, 1770

George Canning (11 April 1770 – 8 August 1827) was a British statesman and politician who served as Foreign Secretary and briefly Prime Minister.

Canning was born at his parents' home in Queen Anne Street, Marylebone, London. His father, George Canning, Sr., of Garvagh, County Londonderry, was a gentleman of limited means, a failed wine merchant and lawyer,

who renounced his right to inherit the family estate in exchange for

payment of his substantial debts. George Sr. eventually abandoned the

family and died in poverty on 11 April 1771, his son's first birthday,

in London. Canning's mother, Mary Anne Costello, took work as a stage actress,

a profession not considered respectable at the time. Because Canning

showed unusual intelligence and promise at an early age, family friends

persuaded his uncle, London merchant Stratford Canning (father to the diplomat Stratford Canning),

to become his nephew's guardian. George Canning grew up with his

cousins at the home of his uncle, who provided him with an income and

an education. Stratford Canning's financial support allowed the young

Canning to study at Eton College and Christ Church, Oxford.

While at school, Canning gained renown for his skill in writing and debate. He struck up friendships with the then-future Lord Liverpool as well as with Granville Leveson-Gower and John Hookham Frere. In 1789 he won a prize for his Latin poem The Pilgrimage to Mecca which he recited in Oxford Theatre. Canning began practising law after receiving his BA from Oxford in the summer of 1791. Yet he wished to enter politics.

Stratford Canning was a Whig and would introduce his nephew in the 1780s to prominent Whigs such as Charles James Fox, Edmund Burke, and Richard Brinsley Sheridan. George Canning's friendship with Sheridan would last for the remainder of Sheridan's life. George

Canning's impoverished background and limited financial resources,

however, made unlikely a bright political future in a Whig party whose

political ranks were led mostly by members of the wealthy landed

aristocracy in league with the newly rich industrialist classes.

Regardless, along with Whigs such as Burke, Canning himself would

become considerably more conservative in the early 1790s after

witnessing the excessive radicalism of the French Revolution. Henry Brooks Adams wrote,

"The political reaction which followed swept the young man to the

opposite extreme: and his vehemence for monarchy gave point to a Whig

sarcasm, - that men had often been known to turn their coats, but this

was the first time that a boy had turned his jacket." So when Canning decided to enter politics he sought and received the patronage of the leader of the "Tory" group, William Pitt the Younger. In 1793, thanks to the help of Pitt, Canning became a Member of Parliament for Newtown on the Isle of Wight, a rotten borough. In 1796, he changed seats to a different rotten borough, Wendover in Buckinghamshire. He was elected to represent several constituencies during

his parliamentary career. Canning

rose quickly in British politics as an effective orator and writer. His

speeches in Parliament as well as his essays gave the followers of Pitt

a rhetorical power they had previously lacked. Canning's skills saw him

gain leverage within the Pittite faction that allowed him influence

over its policies along with repeated promotions in the Cabinet. Over

time, Canning became a prominent public speaker as well, and was one of

the first politicians to campaign heavily in the country. As a result

of his charisma and promise, Canning early on drew to himself a circle

of supporters who would become known as the Canningites. Conversely though, Canning had a reputation as a divisive man who alienated many. He

was a dominant personality and often risked losing political allies for

personal reasons. He once reduced Lord Liverpool to tears with a long

satirical poem mocking Liverpool's attachment to his time as a colonel

in the militia. He then forced Liverpool to apologise for being upset. On 2 November 1795, Canning received his first ministerial post: Under Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. In this post he proved a strong supporter of Pitt, often taking his side in disputes with the Foreign Secretary, Lord Grenville. He resigned this post on 1 April 1799. In 1799 Canning became a commissioner of the Board of Control, followed by Paymaster of the Forces in

1800. When Pitt resigned in 1801, Canning loyally followed him into

opposition and again returned to office in 1804 with Pitt, becoming Treasurer of the Navy. Canning left office with the death of Pitt but was appointed Foreign Secretary in the new government of the Duke of Portland the following year. Given key responsibilities for the country's diplomacy in the Napoleonic Wars, he was responsible for planning the attack on Copenhagen in September 1807, much of which he undertook at his country estate, South Hill Park at Easthampstead in Berkshire. In November 1807, Canning oversaw the Portuguese royal family's flight from

Portugal to Brazil. In 1809 Canning entered into a series of disputes

within the government that were to become famous. He argued with the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, Lord Castlereagh, over the deployment of troops that Canning had promised would be sent to Portugal but which Castlereagh sent to the Netherlands.

The government became increasingly paralysed in disputes between the

two men. Portland was in deteriorating health and gave no lead, until

Canning threatened resignation unless Castlereagh were removed and

replaced by Lord Wellesley. Portland secretly agreed to make this change when it would be possible. Castlereagh

discovered the deal in September 1809 and challenged Canning to a duel.

Canning accepted the challenge and it was fought on 21 September 1809.

Canning, who had never before fired a pistol, widely missed his mark.

Castlereagh, who was regarded as one of the best shots of his day,

wounded his opponent in the thigh. There was much outrage that two

cabinet ministers had resorted to such a method. Shortly afterwards the

ailing Portland resigned as Prime Minister, and Canning offered himself

to George III as a potential successor. However, the King appointed Spencer Perceval instead, and Canning left office once more. He did take consolation, though, in the fact that Castlereagh also stood down. Upon Perceval's assassination in 1812, the new Prime Minister, Lord Liverpool, offered Canning the position of Foreign Secretary once more. Canning refused, as he also wished to be Leader of the House of Commons and was reluctant to serve in any government with Castlereagh. In 1814 he became the British Ambassador to Portugal, returning the following year. He received several further offers of office from Liverpool and in 1816 he became President of the Board of Control. Canning resigned from office once more in 1820, in opposition to the treatment of Queen Caroline, estranged wife of the new King George IV. Canning and Caroline were close friends and may have had a brief sexual affair. This would have been regarded as unacceptable. In 1822, Castlereagh, now Marquess of Londonderry,

committed suicide. Canning succeeded him as both Foreign Secretary and

Leader of the House of Commons. In his second term of office he sought

to prevent South America from coming into the French sphere of influence, and in this he was successful. He

also gave support to the growing campaign for the abolition of slavery.

Despite personal issues with Castlereagh, he continued many of his

foreign policies, such as the view that the powers of Europe (Russia,

France, etc.) should not be allowed to meddle in the affairs of other

states. This policy enhanced public opinion of Canning as a liberal. He

also prevented the United States from opening trade with the West

Indies. In

1827, Liverpool suffered a severe stroke and was to die the following

year. Canning, as Liverpool's right-hand man, was then chosen by George

IV to succeed him, in preference to both the Duke of Wellington and Sir Robert Peel.

Neither man agreed to serve under Canning, and they were followed by

five other members of Liverpool's Cabinet as well as 40 junior members

of the government. The Tory party was now heavily split between the

"High Tories" (or "Ultras", nicknamed after the contemporary party in France) and the moderates supporting Canning, often called "Canningites".

As a result Canning found it difficult to form a government and chose

to invite a number of Whigs to join his Cabinet, including Lord Lansdowne. The government agreed not to discuss the difficult question of parliamentary reform, which Canning opposed but the Whigs supported. However,

Canning's health by this time was in steep decline. He died on 8 August

1827, in the very same room where Charles James Fox met his own end, 21

years earlier. To this day Canning's total period in office remains the

shortest of any Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, a mere 119 days. He is buried in Westminster Abbey. Canning

has come to be regarded as a "lost leader", with much speculation about

what his legacy could have been had he lived. His government of Tories

and Whigs continued for a few months under Lord Goderich but fell apart in early 1828. It was succeeded by a government under the Duke of Wellington, which initially included some Canningites but

soon became mostly "High Tory" when many of the Canningites drifted

over to the Whigs. Wellington's administration would soon go down in

defeat as well. Some historians have seen the revival of the Tories

from the 1830s onwards, in the form of the Conservative Party, as the overcoming of the divisions of 1827. What would have been the course of events had Canning lived is highly speculative. A

central square in Athens, Greece is named after Canning (Canning Square

(Plateia Kanigos)), in appreciation of his supportive stance toward the

Greeks during their War of Independence (1821-1830).