<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Leonhard Paul Euler, 1707

- Painter Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci, 1452

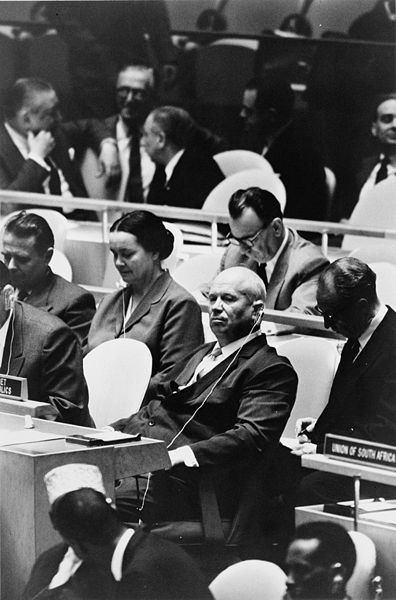

- Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet Nikita Krushchev, 1894

Nikita Khrushchev (April 15, 1894 – September 11, 1971) led the Soviet Union during the Cold War. He served as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964, and as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, or Premier, from 1958 to 1964. Khrushchev was responsible for the partial de-Stalinization of the Soviet Union, for backing the progress of the world's early space program, and for several relatively liberal reforms in areas of domestic policy. Khrushchev's party colleagues removed him from power in 1964, replacing him with Leonid Brezhnev.

Khrushchev was born in the Russian village of Kalinovka in 1894. He was employed as a metalworker in his youth, and during the Russian Civil War was a political commissar. With the help of Lazar Kaganovich, he worked his way up the Soviet hierarchy. He supported Stalin's purges, and approved thousands of arrests. In 1939, Stalin sent him to govern Ukraine, and he continued the purges there. During what was known in the Soviet Union as the "Great Patriotic War"

(World War II), Khrushchev was again a commissar, serving as an

intermediary between Stalin and his generals. Khrushchev was present at

the bloody defense of Stalingrad, a fact he took great pride in throughout his life. After the war, he

returned to Ukraine before being recalled to Moscow as one of Stalin's

close advisers. Stalin's

political heirs fought for power after his death in 1953, a struggle in

which Khrushchev, after several years, emerged triumphant. On February

25, 1956, at the Twentieth Party Congress, he delivered the "Secret Speech", vilifying Stalin and ushering in a less repressive era in

the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). His domestic policies,

aimed at bettering the lives of ordinary Soviets, were often

ineffective, especially in the area of agriculture. Hoping eventually

to rely on missiles for national defense, Khrushchev ordered major cuts

in conventional forces. Despite the cuts, Khrushchev's rule saw the

tensest years of the Cold War, culminating in the Cuban Missile Crisis. Flaws

in Khrushchev's policies eroded his popularity and emboldened potential

opponents, who quietly rose in strength and deposed the premier in

October 1964. However, he did not suffer the deadly fate of previous

losers of Soviet power struggles, and was pensioned off with an

apartment in Moscow and a dacha in

the countryside. His lengthy memoirs were smuggled to the West and

published in part in 1970. Khrushchev died in 1971 of heart disease. Khrushchev was born April 15, 1894, in Kalinovka, a village in what is now Russia's Kursk Oblast. His parents, Sergei Khrushchev and Ksenia Khrushcheva, were poor peasants of Russian origin and had a daughter two years Nikita's junior, Irina. Sergei Khrushchev was employed in a number of positions in the Donbas area

of far eastern Ukraine, working as a railwayman, as a miner, and

laboring in a brick factory. Wages were much higher in the Donbas than

in the Kursk region, and Sergei Khrushchev generally left his family in

Kalinovka, returning there when he had enough money. Kalinovka

was a peasant village; Khrushchev's teacher, Lydia Shevchenko later

stated that she had never seen a village as poor as Kalinovka had been. Nikita worked as a herdsboy from

an early age. He was schooled for a total of four years, part in the

village parochial school and part under Shevchenko's tutelage in

Kalinovka's state school. According to Khrushchev in his memoirs,

Shevchenko was a freethinker who upset the villagers by not attending

church, and when her brother visited, he gave the boy books which had

been banned by the Imperial Government. She urged Nikita to seek further education, but family finances did not permit this. In 1908, Sergei Khrushchev moved to the Donbas city of Yuzovka; fourteen-year-old Nikita followed later that year, while Ksenia Khrushcheva and her daughter came after. Yuzovka was renamed Stalino in 1924 and Donetsk in 1961, and was at the heart of one of the most industrialized areas of the Russian Empire. After

the boy worked briefly in other fields, Nikita's parents found him a

place as a metal fitter's apprentice. Upon completing that

apprenticeship, the teenage Khrushchev was hired by a factory. He lost that job when he collected money for the families of the victims of the Lena Goldfields Massacre, and was hired to mend underground equipment by a mine in nearby Rutchenkovo, where he helped distribute copies and organize public readings of Pravda. He later stated that he considered emigrating to the United States for better wages, but did not do so. When World War I broke out in 1914, Khrushchev, as a skilled metal worker, was exempt from conscription.

Employed by a workshop which serviced ten mines, Khrushchev was

involved in several strikes demanding higher pay, better working

conditions, and an end to the war. In

1914, he married Yefrosinia Pisareva, daughter of the elevator operator

at the Rutchenkovo mine. In 1915, they had a daughter, Yulia, and in

1917, a son, Leonid. After the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II in 1917, the new Russian Provisional Government in St. Petersburg had little influence over Ukraine. Khrushchev was elected to the worker's council (or soviet) in Rutchenkovo, and in May he became its chairman. He did not join the Bolsheviks until 1918, a year in which the Russian Civil War, between the Bolsheviks and a coalition of opponents known as the White Army, began in earnest. In March 1918, as the Bolshevik government concluded a separate peace with the Central Powers, the Germans occupied the Donbas and Khrushchev fled to Kalinovka. In late 1918 or early 1919 he was mobilized into the Red Army as a political commissar. The

post of political commissar had recently been introduced as the

Bolsheviks came to rely less on worker activists and more on military

recruits; its functions included indoctrination of recruits in the

tenets of Bolshevism, and promoting troop morale and battle readiness. Beginning

as commissar to a construction platoon, Khrushchev rose to become

commissar to a construction battalion and was sent from the front for a

two-month political course. The young commissar came under fire many

times. In 1921, the civil war ended,

and Khrushchev was demobilized and assigned as commissar to a labor

brigade in the Donbas, where he and his men lived in poor conditions. The

wars had caused widespread devastation and famine, and one of the

victims of the hunger and disease was Khrushchev's wife, Yefrosinia,

who died of typhus in Kalinovka while Khrushchev was in the army. Through

the intervention of a friend, Khrushchev was assigned in 1921 as

assistant director for political affairs for the Rutchenkovo mine in

the Donbas region, where he had previously worked. There were as yet few Bolsheviks in the area. At that time, the movement was split by Lenin's New Economic Policy, which allowed for some measure of private enterprise and was seen as an ideological retreat by some Bolsheviks. While

Khrushchev's responsibility lay in political affairs, he involved

himself in the practicalities of resuming full production at the mine

after the chaos of the war years. He helped restart the machines (key

parts and papers had been removed by the pre-Soviet mineowners) and he

wore his old mine outfit for inspection tours. Khrushchev

was highly successful at the Rutchenkovo mine, and in mid-1922 he was

offered the directorship of the nearby Pastukhov mine. However, he

refused the offer, seeking to be assigned to the newly established technical college (tekhnikum)

in Yuzovka, though his superiors were reluctant to let him go. As he

had only four years of formal schooling, he applied to the training

program (rabfak) attached to the tekhnikum that was designed to bring undereducated students to high-school level, a prerequisite for entry into the tekhnikum. While enrolled in the rabfak, Khrushchev continued his work at the Rutchenkovo mine. One of his teachers later described him as a poor student. He was more successful in advancing in the Communist Party; soon after his admission to the raikom in August 1922, he was appointed party secretary of the entire tekhnikum,

and became a member of the bureau – the governing council – of the

party committee for the town of Yuzovka (renamed Stalino in 1924). He

briefly joined supporters of Leon Trotsky against those of Joseph Stalin over

the question of party democracy. All of these activities left him with

little time for his studies, and while he later claimed to have

finished his rabfak studies, it is unclear whether this was true. In

1922, Khrushchev met and married his second wife, Marusia. The two soon separated, though Khrushchev would help

Marusia in later years, especially when Marusia's daughter by a

previous relationship suffered a fatal illness. Soon after the abortive

marriage, Khrushchev met Nina Petrovna Kukharchuk, a well-educated

Party organizer and daughter of well-to-do Ukrainian peasants. The

two lived together as husband and wife for the rest of Khrushchev's

life, though they did not register their marriage until 1965. In mid-1925, Khrushchev was appointed Party secretary of the Petrovo-Marinsky raikom, or district, near Stalino. The raikom was about 400 square miles (1,000 km2) in area, and Khrushchev was constantly on the move throughout his domain, taking an interest in even minor matters. In late 1925, Khrushchev was elected a non-voting delegate to the 14th Congress of the USSR Communist Party in Moscow. Khrushchev met Lazar Kaganovich as early as 1917. In 1925, Kaganovich became Party head in Ukraine and Khrushchev, falling under his patronage, was

rapidly promoted. He was appointed second in command of the Stalino

party apparatus in late 1926. Within nine months Khrushchev arranged

the ouster of his superior, Konstantin Moiseyenko. Kaganovich transferred Khrushchev to Kharkov, then the capital of Ukraine, as head of the Organizational Department of the Ukrainian Party's Central Committee. In 1928, Khrushchev was transferred to Kiev, where he served as second-in-command of the Party organization there. In 1929, Khrushchev again sought to further his education, following Kaganovich (now in the Kremlin as

a close associate of Stalin) to Moscow and enrolling in the Stalin

Industrial Academy. Khrushchev never completed his studies there, but

his career in the Party flourished. When the school's Party cell elected a number of rightists to an upcoming district Party conference, the cell was attacked in Pravda. Khrushchev

emerged victorious in the ensuing power struggle, becoming Party

secretary of the school, arranging for the delegates to be withdrawn,

and afterward purging the cell of the rightists. Khrushchev

rose rapidly through the Party ranks, first becoming Party leader for

the Bauman district, site of the Academy, before taking the same

position in the Krasnopresnensky district, the capital's largest and

most important. By 1932, Khrushchev had become second in command,

behind Kaganovich, of the Moscow city Party organization, and in 1934,

he became Party leader for the city and a member of the Party's Central Committee. While head of the Moscow city organization, Khrushchev superintended construction of the Moscow Metro,

a highly expensive undertaking, with Kaganovich in overall charge.

Faced with an already-announced opening date of November 7, 1934,

Khrushchev took considerable risks in the construction and spent much

of his time down in the tunnels. When the inevitable accidents did

occur, they were depicted as heroic sacrifices in a great cause. The

Metro did not open until May 1, 1935, but Khrushchev received the Order of Lenin for his role in its construction. Later that year, he was selected as Party leader for Moscow oblast, a province with a population of 11 million. Beginning in 1934, Stalin began murderous purges of the Party through a series of show trials.

In 1936, as the trials proceeded, Khrushchev expressed his vehement

support. Khrushchev assisted in the purge of many friends and

colleagues in Moscow oblast. Of 38 top Party officials in Moscow city and province, 35 were killed—the three survivors were transferred to other parts of the USSR. Of the 146 Party secretaries of cities and districts outside Moscow city in the province, only 10 survived the purges. In his memoirs, Khrushchev noted that almost everyone who worked with him was arrested. By

Party protocol, Khrushchev was required to approve these arrests, and

did little or nothing to save his friends and colleagues. Party leaders were given numerical quotas of "enemies" to be turned in and arrested. In June 1937, the Politburo set

a quota of 35,000 enemies to be arrested in Moscow province; 5,000

of these were to be executed. In reply, Khrushchev asked that

2,000 wealthy peasants, or kulaks living

in Moscow be killed in part fulfillment of the quota. In any event,

only two weeks after receiving the Politburo order, Khrushchev was able

to report to Stalin that 41,305 "criminal and kulak elements" had been arrested. Of the arrestees, according to Khrushchev, 8,500 deserved execution. Khrushchev became a candidate member of the Politburo in January 1938 and a full member in March 1939. In

late 1937, Stalin appointed Khrushchev as head of the Communist Party

in Ukraine, and Khrushchev duly left Moscow for Kiev, again the

Ukrainian capital, in January 1938. Ukraine

had been the site of extensive purges, with the murdered including

professors in Stalino whom Khrushchev greatly respected. The high ranks

of the Party were not immune; the Central Committee of Ukraine was so

decimated that it could not convene a quorum. After Khrushchev's

arrival, the pace of arrests accelerated. All

but one member of the Ukrainian Politburo Organizational Bureau, and

Secretariat were arrested. Almost all government officials and Red Army

commanders were replaced. During the first few months after Khrushchev's arrival, almost everyone arrested received the death penalty. When Soviet troops, pursuant to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, invaded the eastern portion of Poland on

September 17, 1939, Khrushchev accompanied the troops at Stalin's

direction. Much of the invaded area was ethnically Ukrainian and today

forms the western portion of Ukraine. Many inhabitants had been badly

treated by the Poles and initially welcomed the invasion, though they

hoped that they would eventually become independent. Khrushchev's role

was to ensure that the occupied areas voted for union with the USSR.

Through a combination of propaganda, deception as to what was being

voted for, and outright fraud, the Soviets ensured that their new

territories would elect assemblies which would unanimously petition for

union with the USSR. When the new assemblies did so, their petitions

were granted by the USSR Supreme Soviet, and Western Ukraine became a

part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR) on November 1,

1939. Clumsy

actions by the Soviets, such as staffing Western Ukrainian

organizations with Eastern Ukrainians, and giving confiscated land to

collective farms (kolkhozes) rather than to peasants soon alienated Western Ukrainians, despite Khrushchev's efforts to achieve unity. When the Germans invaded the USSR, in June 1941, Khrushchev was still at his post in Kiev. Stalin

appointed him a political commissar, and Khrushchev served on a number

of fronts as an intermediary between the local military commanders and

the political rulers in Moscow. Stalin used Khrushchev to keep

commanders on a tight leash, while the commanders sought to have him

influence Stalin. As

the Germans advanced, Khrushchev worked with the military in an attempt

to defend and save the city. Handicapped by orders from Stalin that

under no circumstances should the city be abandoned, the Red Army was

soon encircled by the Germans.

While the Germans stated they took 655,000 prisoners, according to

the Soviets, 150,541 men out of 677,085 escaped the trap. Khrushchev noted in his memoirs that he and Marshal Semyon Budyonny proposed redeploying Soviet forces to avoid the encirclement until Marshal Semyon Timoshenko arrived from Moscow with orders for the troops to hold their positions. In 1942, Khrushchev was on the Southwest Front, and he and Timoshenko proposed a massive counteroffensive in the Kharkov area.

Stalin approved only part of the plan, but 640,000 Red Army

soldiers would still become involved in the offensive. The Germans,

however, had deduced that the Soviets were likely to attack at Kharkov,

and set a trap. Beginning on May 12, 1942, the Russian offensive

initially appeared successful, but within five days the Germans had

driven deep into the Soviet flanks, and the Red Army troops were in

danger of being cut off. Stalin refused to halt the offensive, and the

Red Army divisions were soon encircled by the Germans. The USSR lost

about 267,000 soldiers, including more than 200,000 men

captured, and Stalin demoted Timoshenko and recalled Khrushchev to

Moscow. While Stalin hinted at arresting and executing Khrushchev, he

allowed the commissar to return to the front by sending him to Stalingrad. Khrushchev reached the Stalingrad Front in August 1942, soon after the start of the battle for the city. His role in the Stalingrad defense was not major. Though

he visited Stalin in Moscow on occasion, he remained in Stalingrad for

much of the battle, and was nearly killed at least once. He proposed a

counterattack, only to find that Zhukov and other generals had already

planned Operation Uranus, a plan to break out from Soviet positions and encircle and destroy the Germans; it was being kept secret. Soon

after Stalingrad, Khrushchev met with personal tragedy, as his son

Leonid, a fighter pilot, was apparently shot down and killed in action

on March 11, 1943. The circumstances of Leonid's death remain obscure

and controversial, as

none of his fellow fliers stated that they witnessed him being shot

down, nor was his plane found or body recovered. In

mid-1943, Leonid's wife, Liuba Khrushcheva, was arrested on accusations

of spying and sentenced to five years in a labor camp, and her son (by

another relationship), Tolya, was placed in a series of orphanages.

Leonid's daughter, Yulia, was raised by Nikita Khrushchev and his wife. After Uranus forced the Germans into retreat, Khrushchev served in other fronts of the war. He was attached to Soviet troops at the Battle of Kursk, in July 1943, which turned back the last major German offensive on Soviet soil. He

accompanied Soviet troops as they took Kiev in November 1943, entering

the shattered city as Soviet forces drove out German troops. As

Soviet forces met with greater success, driving the Nazis westwards

towards Germany, Nikita Khrushchev became increasingly involved in

reconstruction work in Ukraine. He was appointed Premier of the

Ukrainian SSR in addition to his earlier party post, one of the rare

instances in which the Ukrainian party and civil leader posts were held

by one person. Almost

all of Ukraine had been occupied by the Germans, and Khrushchev

returned to his domain in late 1943 to find devastation. Ukraine's

industry had been destroyed, and agriculture faced critical shortages.

Even though millions of Ukrainians had been taken to Germany as workers

or prisoners of war, there was insufficient housing for those who

remained. One of every six Ukrainians was killed in World War II. Khrushchev

sought to reconstruct Ukraine, but also desired to complete the

interrupted work of imposing the Soviet system on it, though he hoped

that the purges of the 1930s would not recur. As

Ukraine was recovered, conscription was imposed, and 750,000 men

aged between nineteen and fifty were given minimal military training

and sent to join the Red Army. Other Ukrainians joined partisan forces, seeking an independent Ukraine. Khrushchev

rushed from district to district through Ukraine, urging the depleted

labor force to greater efforts. He made a short visit to his birthplace

of Kalinovka, finding a starving population, with only a third of the

men who had joined the Red Army having returned. Khrushchev did what he

could to assist his hometown. Despite

Khrushchev's efforts, in 1945, Ukrainian industry was at only a quarter

of pre-war levels, and the harvest actually dropped from that of 1944,

when the entire territory of Ukraine had not yet been retaken. In an effort to increase agricultural production, the kolkhozes (collective farms) were empowered to expel residents who were not pulling their weight. Kolkhoz leaders

used this as an excuse to expel their personal enemies, invalids, and

the elderly, and nearly 12,000 people were sent to the eastern

parts of the Soviet Union. Khrushchev viewed this policy as very

effective, and recommended its adoption elsewhere to Stalin. He also worked to impose collectivization on

Western Ukraine. While Khrushchev hoped to accomplish this by 1947,

lack of resources and armed resistance by partisans slowed the process. The partisans, many of whom fought as the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UIA),

were gradually defeated, as Soviet police and military reported killing

110,825 "bandits" and capturing a quarter million more between 1944 and

1946. About

600,000 Western Ukrainians were arrested between 1944 and 1952,

with one-third executed and the remainder imprisoned or exiled to the

east. The

war years of 1944 and 1945 had seen poor harvests, and 1946 saw intense

drought strike Ukraine and Western Russia. Despite this, collective and

state farms were required to turn over 52% of the harvest to the

government. The Soviet government sought to collect as much grain as possible in order to supply communist allies in Eastern Europe. Khrushchev set the quotas at a high level, leading Stalin to expect an unrealistically large quantity of grain from Ukraine. Food

was rationed—but non-agricultural rural workers throughout the USSR

were given no ration cards. The inevitable starvation was largely

confined to remote rural regions, and was little noticed outside the

USSR. Khrushchev,

realizing the desperate situation in late 1946, repeatedly appealed to

Stalin for aid, to be met with anger and resistance on the part of the

leader. When letters to Stalin had no effect, Khrushchev flew to Moscow

and made his case in person. Stalin finally gave Ukraine limited food

aid, and money to set up free soup kitchens. However,

Khrushchev's political standing had been damaged, and in February 1947,

Stalin suggested that Lazar Kaganovich be sent to Ukraine to "help"

Khrushchev. The

following month, the Ukrainian Central Committee removed Khrushchev as

party leader in favor of Kaganovich, while retaining him as premier. Soon

after Kaganovich arrived in Kiev, Khrushchev fell ill, and was barely

seen until September 1947. In his memoirs, Khrushchev indicates he had

pneumonia. By

the end of 1947, Kaganovich had been recalled to Moscow and the

recovered Khrushchev had been restored to the First Secretaryship. He

then resigned the Ukrainian premiership in favor of Demyan Korotchenko, Khrushchev's protégé. Khrushchev's final years in Ukraine were generally peaceful, with industry recovering, Soviet forces overcoming the partisans, and 1947 and 1948 seeing better-than-expected harvests. Collectivization

advanced in Western Ukraine, and Khrushchev implemented more policies

that encouraged collectivization and discouraged private farms. Khrushchev

attributed his recall to Moscow to mental disorder on the part of

Stalin, who feared conspiracies in Moscow matching those which the

ruler believed to have occurred in the fabricated Leningrad case, in which many of that city's Party officials had been falsely accused of treason. Khrushchev

again served as head of the Party in Moscow city and province.

Khrushchev biographer Taubman suggests that Stalin most likely recalled

Khrushchev to Moscow to balance the influence of Georgy Malenkov and security chief Lavrentiy Beria, who were widely seen as Stalin's heirs. At

this time, the aging dictator rarely called Party meetings. Instead,

much of the high-level work of government took place at dinners hosted

by Stalin. These sessions, which Beria, Malenkov, Khrushchev, and Nikolai Bulganin, who comprised Stalin's inner circle, attended, began with showings of cowboy movies favored by Stalin. Stolen

from the West, they lacked subtitles. The dictator had the meal served

at around 1 a.m., and insisted that his subordinates stay with him

and drink until dawn. On one occasion, Stalin had Khrushchev, then aged

almost sixty, dance a traditional Ukrainian dance. Khrushchev did so, later stating, "When Stalin says dance, a wise man dances." Khrushchev

attempted to nap at lunch so that he would not fall asleep in the

dictator's presence; he noted in his memoirs, "Things went badly for

those who dozed off at Stalin's table." In

1950, Khrushchev began a large-scale housing program for Moscow. A

large part of the housing was in the form of five- or six-story

apartment buildings, which became ubiquitous throughout the Soviet

Union; many remain in use today. Khrushchev had prefabricated reinforced concrete used, greatly speeding up construction. These

structures were completed at triple the construction rate of Moscow

housing from 1946–50, lacked elevators or balconies, and were nicknamed Khrushcheby by the public, a pun on the Russian word for slums, trushcheby. Almost 60,000,000 residents of the former Soviet republics still live in these buildings. In his new positions, Khrushchev continued his kolkhoz consolidation

scheme, decreasing the number of collective farms in Moscow province by

about 70%. This resulted in farms which were too large for one chairman

to manage effectively. Khrushchev also sought to implement his agro-town proposal, but when his lengthy speech on the subject was published in Pravda in

March 1951, Stalin disapproved of it. The periodical quickly published

a note stating that Khrushchev's speech was merely a proposal, not

policy. In April, the Politboro disavowed the agro-town proposal.

Khrushchev feared that Stalin would remove him from office, but the

leader mocked Khrushchev, then allowed the episode to pass. On

March 1, 1953, Stalin suffered a massive stroke, apparently on rising

after sleep. Stalin had left orders not to be disturbed, and it was

twelve hours until his condition was discovered. Even as terrified

doctors attempted treatment, Khrushchev and his colleagues engaged in

intense discussion as to the new government. On March 5, Stalin died.

As Khrushchev and other high officials stood weeping by Stalin's

bedside, Beria raced from the room, shouting for his car. On

March 6, 1953, Stalin's death was announced, as was the new leadership.

Malenkov was the new Chairman of the Council of Ministers, with Beria, Kaganovich,

Bulganin and former Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov as first vice-chairmen. The Presidium had effectively replaced the Politburo the previous year; those of its

members who had been recently promoted by Stalin were demoted. Khrushchev was relieved of his duties as Party head for Moscow to

concentrate on unspecified duties in the Party's Central Committee. The New York Times listed Malenkov and Beria first and second among the ten-man Presidium—and Khrushchev last. On March 14, Malenkov yielded his post as senior secretary of the Central Committee to Khrushchev. In September, Khrushchev was elected by the Central Committee as First Secretary of the Party. Even

before Stalin had been laid to rest, Beria launched a lengthy series of

reforms which would rival those of Khrushchev during his period of

power and even those of Mikhail Gorbachev a third of a century later. Beria's proposals were designed to denigrate Stalin and pass the blame for Beria's own crimes to the late leader. One proposal, which was adopted, was an amnesty which would eventually free over a million prisoners. Another, which was not, was to release East Germany into a united, neutral Germany in exchange for compensation from the West—a proposal considered by Khrushchev to be anti-communist. Khrushchev

allied with Malenkov to block many of Beria's proposals, while the two

slowly picked up support from other Presidium members. Their campaign

against Beria was aided by fears that Beria was planning a military

coup, and, according to Khrushchev in his memoirs, by the conviction that "Beria is getting his knives ready for us." The

arrest of Beria took place on June 26, 1953 at a Presidium meeting,

following extensive military preparations aimed at heading off a

possible civil war. Beria was tried in secret, and executed in December

1953 with five of his close associates. The execution of Beria proved

to be the last time the loser of a top-level power struggle in the USSR

paid with his life. The

power struggle in the Presidium was not resolved by the elimination of

Beria. Malenkov's power was in the central state apparatus, which he

sought to extend through reorganizing the government, giving it

additional power at the expense of the party. He also sought public

support by lowering retail prices and lowering the level of bond sales

to citizens, which had long been effectively obligatory. Khrushchev, on

the other hand, with his power base in the Party, sought to both

strengthen the Party and his position within it. While, under the

Soviet system, the Party was to be preeminent, it had been greatly

drained of power by Stalin, who had given much of that power to himself

and to the Politboro (later, to the Presidium). Khrushchev saw that

with the Presidium in conflict, the Party and its Central Committee

might again become powerful. Khrushchev

carefully cultivated high Party officials, and was able to appoint

supporters as local Party bosses, who then took seats on the Central

Committee. Khrushchev

presented himself as a down-to-earth activist prepared to take up any

challenge, contrasting with Malenkov who, though sophisticated, came

across as colorless. Khrushchev arranged for the Kremlin grounds to be opened to the public, an act with "great public resonance". While both Malenkov and Khrushchev sought reforms to agriculture, Khrushchev's proposals were broader, and included the Virgin Lands Campaign, under which hundreds of thousands of young volunteers would settle and farm areas of Western Siberia and Northern Kazakhstan. While the scheme eventually became a tremendous disaster for Soviet agriculture, it was initially successful. In addition, Khrushchev possessed incriminating information on Malenkhov, taken from Beria's secret files. As

Soviet prosecutors investigated the atrocities of Stalin's last years,

including the Leningrad case, they came across evidence of Malenkov's

involvement. Beginning

in February 1954, Khrushchev replaced Malenkov in the seat of honor at

Presidium meetings; in June, Malenkov ceased to head the list of

Presidium members, which was thereafter organized in alphabetical

order. Khrushchev's influence continued to increase, winning the

allegiance of local party heads, and with his nominee heading the KGB. At

a Central Committee meeting in January 1955, Malenkov was accused of

involvement in atrocities, and the committee passed a resolution

accusing him of involvement in the Leningrad case, and of facilitating

Beria's climb to power. At a meeting of the mostly ceremonial Supreme Soviet the following month, Malenkov was demoted in favor of Bulganin, to the surprise of Western observers. Malenkov remained in the Presidium as Minister of Electric Power Stations. After

the demotion of Malenkov, Khrushchev and Molotov initially worked

together well, and the longtime foreign minister even proposed that

Khrushchev, not Bulganin, replace Malenkov as premier. However,

Khrushchev and Molotov increasingly differed on policy. Molotov opposed

the Virgin Lands policy, proposing heavy investment to increase yields

in developed agricultural areas, which Khrushchev felt was not feasible

due to a lack of resources and a lack of a sophisticated farm labor

force. The

two differed on foreign policy as well; soon after Khrushchev took

power, he sought a peace treaty with Austria, which would allow Soviet

troops then in occupation of part of the country to leave. Molotov was

resistant, but Khrushchev arranged for an Austrian delegation to come

to Moscow and negotiate the treaty. Although

Khrushchev and other Presidium members attacked Molotov at a Central

Committee meeting in mid-1955, accusing him of conducting a foreign

policy which turned the world against the USSR, Molotov remained in his

position. By the end of 1955, thousands of political prisoners had returned home, and told their experiences of the gulag labor camps. Continuing investigation into the abuses brought home the full breadth of Stalin's

crimes to his successors. Khrushchev believed that once the stain of

Stalinism was removed, the Party would inspire loyalty among the people. Beginning in October 1955, Khrushchev fought to tell the delegates to the upcoming 20th Party Congress about

Stalin's crimes. Some of his colleagues, including Molotov and

Malenkov, opposed the disclosure, and managed to persuade him to make

his remarks in a closed session. The

20th Party Congress opened on February 14, 1956. In his opening words

in his initial address, Khrushchev denigrated Stalin by asking

delegates to rise in honor of the communist leaders who had died since

the last congress, whom he named, equating Stalin with the drunken Klement Gottwald and the little-known Kyuichi Tokuda. In the early morning hours of February 25, Khrushchev delivered what became known as the "Secret Speech"

to a closed session of the Congress limited to Soviet delegates. In

four hours, he demolished Stalin's reputation. The

Secret Speech, while it did not fundamentally change Soviet society,

had wide-ranging effects. The speech was a factor in unrest in Poland

and revolution in Hungary later in 1956, and Stalin defenders led four days of rioting in his native Georgia in June, calling for Khrushchev to resign and Molotov to take over. In

meetings where the Secret Speech was read, communists would make even

more severe condemnations of Stalin (and of Khrushchev), and even call

for multi-party elections. However, Stalin was not publicly denounced,

and his portrait remained widespread through the USSR, from airports to

Khrushchev's Kremlin office. The

term "Secret Speech" proved to be an utter misnomer. While the

attendees at the Speech were all Soviet, Eastern European delegates

were allowed to hear it the following night, read slowly to allow them

to take notes. By March 5, copies were being mailed throughout the

Soviet Union, marked "not for the press" rather than "top secret". An

official translation appeared within a month in Poland; the Poles

printed 12,000 extra copies, one of which soon reached the West. The

anti-Khrushchev minority in the Presidium was augmented by those

opposed to Khrushchev proposals to decentralize authority over

industry, which struck at the heart of Malenkov's power base. During

the first half of 1957, Malenkov, Molotov, and Kaganovich worked to

quietly build support to dismiss Khrushchev. At a June 18 Presidium

meeting at which two Khrushchev supporters were absent, the plotters

moved that Bulganin, who had joined the scheme, take the chair, and

proposed other moves which would effectively demote Khrushchev and put

themselves in control. Khrushchev objected on the grounds that not all

Presidium members had been notified, an objection which would have been

quickly dismissed had Khrushchev not held firm control over the

military, through Minister of Defense Marshal Zhukov, and the security

departments. Lengthy Presidium meetings took place, continuing over

several days. As word leaked of the power struggle, members of the

Central Committee, which Khrushchev controlled, streamed to Moscow,

many flown there aboard military planes, and demanded to be admitted to

the meeting. While they were not admitted, there were soon enough

Central Committee members in Moscow to call an emergency Party

Congress, which effectively forced the leadership to allow a session of

the Central Committee. At that meeting, the three main conspirators

were dubbed the Anti-Party Group,

accused of factionalism and complicity in Stalin's crimes. The three

were expelled from the Central Committee and Presidium, as was former

Foreign Minister and Khrushchev client Dmitri Shepilov who joined them in the plot. Molotov was sent as Ambassador to Mongolia; the others were sent to head industrial facilities and institutes far from Moscow. Marshal

Zhukov was rewarded for his support with full membership in the

Presidium, but Khrushchev feared his popularity and power. In October,

the defense minister was sent on a tour of the Balkans, as Khrushchev

arranged a Presidium meeting to dismiss him. Zhukov learned what was

happening, and hurried back to Moscow, only to be formally notified of

his dismissal. At a Central Committee meeting several weeks later, not

a word was said in Zhukov's defense. Khrushchev

completed the consolidation of power by arranging for Bulganin's

dismissal as premier in favor of himself (Bulganin was sent to head the Gosbank) and by establishing a USSR Defense Council, led by himself, effectively making him commander in chief. Though Khrushchev was now preeminent, he did not enjoy Stalin's absolute power. After assuming power, Khrushchev allowed a modest amount of freedom in the arts. Khrushchev

believed that the USSR could match the West's living standards, and was

not afraid to allow Soviet citizens to see Western achievements. Stalin had permitted few tourists to the Soviet Union, and had allowed few Soviets to travel. Khrushchev

let Soviets travel and allowed foreigners to visit the Soviet Union, where tourists

became subjects of immense curiosity. In 1962, Khrushchev, impressed by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, persuaded the Presidium to allow publication. That renewed thaw ended on December 1, 1962, when Khrushchev was taken to the Manezh Gallery to view an exhibit which included a number of avant-garde works. On seeing them, Khrushchev exploded with anger, describing the artwork as "dog shit", and a week later, Pravda issued

a call for artistic purity. When writers and filmmakers defended the

painters, Khrushchev extended his anger to them. However, despite the

premier's rage, none of the artists were arrested or exiled. Under Khrushchev, the special tribunals operated by security agencies were abolished. These tribunals (known as troikas),

had often ignored laws and procedures. Under the reforms, no

prosecution for a political crime could be brought even in the regular

courts unless approved by the local Party committee. This rarely

happened; there were no major political trials under Khrushchev, and at

most several hundred political prosecutions overall. Instead, other

sanctions were imposed on dissidents, including loss of job or

university place, or expulsion from the Party. During Khrushchev's

rule, forced hospitalization for the "socially dangerous" was

introduced. In

1958, Khrushchev opened a Central Committee meeting to hundreds of

Soviet officials; some were even allowed to address the meeting. For

the first time, the proceedings of the Committee were made public in

book form; a practice which was continued at subsequent meetings. In 1962, Khrushchev divided oblast (province)

level Party committees into two parallel structures, one for industry

and one for agriculture. This was unpopular among Party apparatchiks,

and led to confusions in the chain of command, as neither committee

secretary had precedence over the other. As there were limited numbers

of Central Committee seats from each oblast,

the division set up the possibility of rivalry for office between

factions. Khrushchev

also ordered that one-third of the membership of each committee, from

low-level councils to the Central Committee itself, be replaced at each

election. This decree created tension between Khrushchev and the

Central Committee and upset the party leaders upon whose support Khrushchev had risen to power. Since the 1940s, Khrushchev had advocated the cultivation of corn in the Soviet Union. He established a corn institute in Ukraine and ordered thousands of acres to be planted with corn in the Virgin Lands. In February 1955, Khrushchev gave a speech in which he advocated an Iowa-style

corn belt in the Soviet Union, and a Soviet delegation visited the US

state that summer. Khrushchev

sought to abolish the Machine-Tractor Stations (MTS) which not only

owned most large agricultural machines such as combines and tractors,

but also provided services such as plowing, and transfer their

equipment and functions to the kolkhozes and sovkhozes (state farms). Without the MTS, the market for Soviet agricultural equipment fell apart, as the kolkhozes now had neither the money nor skilled buyers to purchase new equipment. One adviser to Khrushchev was Trofim Lysenko,

who promised greatly increased production with minimal investment. Such

schemes were attractive to Khrushchev, who ordered them implemented.

Lysenko managed to maintain his influence under Khrushchev despite

repeated failures; as each proposal failed, he advocated another.

Lysenko's influence greatly retarded the development of genetic science

in the Soviet Union. In

1959, Khrushchev announced a goal of overtaking the United States in

production of milk, meat, and butter. Local officials, with

Khrushchev's encouragement, made unrealistic pledges of production.

These goals were met by forcing farmers to slaughter their breeding

herds and by purchasing meat at state stores, then reselling it back to

the government, artificially increasing recorded production. Drought

struck the Soviet Union in 1963; the harvest of 107,500,000 short

tons (97,500,000 t) of grain was down from a peak of

134,700,000 short tons (122,200,000 t) in 1958. The shortages resulted in bread lines, a fact at first kept from Khrushchev. Reluctant to purchase food in the West, but

faced with the alternative of widespread hunger, Khrushchev exhausted

the nation's hard currency reserves and expended part of its gold

stockpile in the purchase of grain and other foodstuffs. While visiting the United States in 1959, Khrushchev was greatly impressed by the agricultural education program at Iowa State University,

and sought to imitate it in the Soviet Union. At the time, the main

agricultural college in the USSR was in Moscow, and students did not do

the manual labor of farming. Khrushchev proposed to move the programs

to rural areas. He was unsuccessful, due to resistance from professors

and students, who never actually disagreed with the premier, but who

did not carry out his proposals. Khrushchev founded several academic towns, such as Akademgorodok. The premier believed that Western science flourished because many scientists lived in university towns such as Oxford,

isolated from big city distractions, and had pleasant living conditions

and good pay. He sought to duplicate those conditions in the Soviet

Union. Khrushchev's attempt was generally successful, though his new

towns and scientific centers tended to attract younger scientists, with

older ones unwilling to leave Moscow or Leningrad. Khrushchev

also proposed to restructure Soviet high schools. While the high

schools provided a college preparatory curriculum, in fact few Soviet

youths went on to university. Khrushchev wanted to shift the focus of

secondary schools to vocational training. While

the vocational proposal would not survive Khrushchev's downfall, a

longer-lasting change was the establishment of specialized high schools

for gifted students or those wishing to study a specific subject. In 1962, a special summer school was established in Novosibirsk to

prepare students for a Siberian math and science Olympiad. The

following year, the Novosibirsk Maths and Science Boarding-School

became the first permanent residential school specializing in math and

science. Other such schools were soon established in Moscow, Leningrad,

and Kiev. By the early 1970s, over 100 specialized schools had been

established, in mathematics, the sciences, art, music, and sport. Preschool

education was increased as part of Khrushchev's reforms, and by the

time he left office, about 22% of Soviet children attended

preschool—about half of urban children, but only about 12% of rural

children. Khrushchev sought to find a lasting solution to the problem of a divided Germany and of the enclave of West Berlin deep

within East German territory. In November 1958, calling West Berlin a

"malignant tumor", he gave the United States, United Kingdom and France

six months to conclude a peace treaty with both German states and the

Soviet Union. If one was not signed, Khrushchev stated, the Soviet

Union would conclude a peace treaty with East Germany. This would leave

East Germany, which was not a party to treaties giving the Western

Powers access to Berlin, controlling the routes to the city. This ultimatum caused dissent among the Western Allies, who were reluctant to go to war over the issue. Khrushchev, however, repeatedly extended the deadline. Khrushchev sought to eliminate many conventional weapons, and defend the Soviet Union with missiles. He

believed that unless this occurred, the huge Soviet military would

continue to eat up resources, making Khrushchev's goals of improving

Soviet life difficult to achieve. In

1955, Khrushchev abandoned Stalin's plans for a large navy, believing

that the new ships would be too vulnerable to either conventional or

nuclear attack. In

January 1960, Khrushchev took advantage of improved relations with the

US to order a reduction of one-third in the size of Soviet armed

forces, alleging that advanced weapons would make up for the lost

troops. While

conscription of Soviet youth remained in force, exemptions from

military service became more and more common, especially for students. The Soviets had few operable ICBMs;

in spite of this Khrushchev publicly boasted of the Soviets' missile

programs, stating that Soviet weapons were many and numerous. The Soviet space program, which Khrushchev firmly supported, appeared to confirm his claims when the Soviets launched Sputnik 1 into orbit, a launch many westerners, including United States Vice President Richard Nixon were convinced was a hoax. When

it became clear that the launch was real, and Sputnik 1 was in orbit,

Western governments concluded that the Soviet ICBM program was further

along than it actually was. In 1959, during Nixon's visit to the Soviet Union, Khrushchev took part in what later became known as the Kitchen Debate, as Nixon and Khrushchev had a impassioned argument in a model kitchen at the American National Exhibition in Moscow, with each defending the economic system of his country. Khrushchev

was invited to visit the United States, and did so that September,

spending thirteen days. The first visit by a Soviet premier to the

United States resulted in an extended media circus. Khrushchev

brought his wife, Nina Petrovna, and adult children with him, though it

was not usual for Soviet officials to travel with their families. The

peripatetic premier visited New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco

(visiting a supermarket), Iowa (visiting Garst's farm), Pittsburgh, and

Washington, concluding with a meeting with US President Eisenhower at Camp David. Khrushchev was originally supposed to visit Disneyland, but the visit was canceled for security reasons, much to his disgruntlement. He did, however, visit Eleanor Roosevelt at her home in Hyde Park, New York. While visiting Thomas J. Watson, Jr's IBM headquarters,

Khrushchev expressed little interest in the computers, but greatly

admired the self-service cafeteria, and, on his return, introduced

self-service in the Soviet Union. Khrushchev's US visit resulted in an informal agreement with US president Dwight Eisenhower that

there would be no firm deadline over Berlin, but that there would be a

four-power summit to try to resolve the issue, and the premier left the

US to general good feelings. A constant irritant in Soviet–US relations was the overflight of the Soviet Union by American U-2 spy aircraft.

On April 9, 1960, the US resumed such flights after a lengthy break.

The Soviets had protested the flights in the past, but had been ignored

by Washington. Content in what he thought was a strong personal

relationship with Eisenhower, Khrushchev was confused and angered by

the flights' resumption, and concluded that they had been ordered by CIA Director Allen Dulles without the US President's knowledge. On May 1, a U-2 was shot down; its pilot, Francis Gary Powers captured alive. Believing

Powers to have been killed, the US announced that a weather plane had

been lost near the Turkish-Soviet border. Khrushchev risked destroying

the summit, due to start on May 16 in Paris, if he announced the

shootdown, but would look weak in the eyes of his military and security

forces if he did nothing. Finally,

on May 5, Khrushchev announced the shootdown and Powers's capture,

blaming the overflight on "imperialist circles and militarists, whose

stronghold is the Pentagon", and suggesting the plane had been sent

without Eisenhower's knowledge. Eisenhower

could not have it thought that there were rogue elements in the

Pentagon operating without his knowledge, and admitted that he had

ordered the flights, calling them "a distasteful necessity". The

admission stunned Khrushchev, and turned the U-2 affair from a possible

triumph to a disaster for him, and he even appealed to US Ambassador Llewellyn Thompson for help. Khrushchev

was undecided what to do at the summit even as he boarded his flight to

Paris. He finally decided, in consultation with his advisers on the

plane and Presidium members in Moscow, to demand an apology from

Eisenhower and a promise that there would be no further U-2 flights in

Soviet airspace. Neither

Eisenhower nor Khrushchev communicated with the other in the days

before the summit, and at the summit, Khrushchev made his demands and

stated that there was no purpose in the summit, which should be

postponed for six to eight months, that is until after the 1960 United States presidential election. The US President offered no apology, but stated that the flights had been suspended and would not resume, and renewed his Open Skies proposal for mutual overflight rights. This was not enough for Khrushchev, who left the summit. Eisenhower's

visit to the Soviet Union, for which the premier had even built a golf

course so the US President could enjoy his favorite sport, was canceled by Khrushchev. Khrushchev

made his second and final visit to the United States in September 1960.

He had no invitation, but had appointed himself as head of the USSR's

UN delegation. He spent much of his time wooing the new Third World states which had recently become independent. The US restricted him to the island of Manhattan, with visits to an estate owned by the USSR on Long Island. The notorious shoe-banging incident occurred during a debate on October 12 over a Russian resolution decrying colonialism. Infuriated by a statement of the Filipino delegate Lorenzo Sumulong which

charged the Soviets with employing a double standard by decrying

colonialism while dominating Eastern Europe, Khrushchev demanded the

right to reply immediately, and accused Sumulong of being "a fawning

lackey of the American imperialists". Sumulong resumed his speech, and

accused the Soviets of hypocrisy. Khrushchev yanked off his shoe and

began banging it on his desk, joined (less loudly) by Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko. This behavior by Khrushchev scandalized his delegation. Khrushchev

considered US Vice President Nixon a hardliner, and was delighted by

his defeat in the 1960 presidential election. He considered the victor, Massachusetts Senator John F. Kennedy,

as a far more likely partner for détente, but was taken aback by

the newly inaugurated US President's tough talk and actions in the

early days of his administration. Khrushchev achieved a propaganda victory in April 1961 with the first manned spaceflight and Kennedy a defeat with the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion.

While Khrushchev had threatened to defend Cuba with Soviet missiles,

the premier contented himself with after-the-fact aggressive remarks.

The failure in Cuba led to Kennedy's determination to make no

concessions at the Vienna summit scheduled

for June 3, 1961. Both Kennedy and Khrushchev took a hard line, with

Khrushchev demanding a treaty that would recognize the two German

states and refusing to yield on the remaining issues obstructing a

test-ban treaty. Kennedy on the other hand had been led to believe that

the test-ban treaty could be concluded at the summit, and felt that a

deal on Berlin had to await easing of East-West tensions. An

indefinite postponement of action over Berlin was unacceptable to

Khrushchev if for no other reason that East Germany was suffering a

continuous "brain drain" as highly educated East Germans fled west

through Berlin. While the boundary between the two German states had

elsewhere been fortified, Berlin, administered by the four Allied

powers, remained open. Emboldened by statements from former US

Ambassador to Moscow Charles E. Bohlen and United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations Chairman J. William Fulbright that

East Germany had every right to close its borders, which were not

disavowed by the Kennedy Administration, Khrushchev authorized East

German leader Walter Ulbricht to begin construction of what became known as the Berlin Wall,

which would surround West Berlin. Construction preparations were made

in great secrecy, and the border was sealed off in the early hours of

Sunday, August 13, 1961, when most East German workers who earned hard

currency by working in West Berlin would be at their homes. The Wall

was a propaganda disaster, and marked the end of Khrushchev's attempts

to conclude a peace treaty among the Four Powers and the two German

states. That treaty would not be signed until September 1990, as an immediate prelude to German reunification. Superpower tensions culminated in the Cuban Missile Crisis (in

the USSR, the "Caribbean crisis") of October 1962, as the Soviet Union

sought to install medium range nuclear missiles in Cuba, about ninety

miles from the US coast. Cuban President Fidel Castro was

reluctant to accept the missiles, and, once he was persuaded, warned

Khrushchev against transporting the missiles in secret. On

October 16, Kennedy was informed that U-2 flights over Cuba had

discovered what were most likely medium-range missile sites, and though

he and his advisors considered approaching Khrushchev through

diplomatic channels, could come up with no way of doing this that would

not appear weak. On

October 22, Kennedy addressed his nation by television, revealing the

missiles' presence and announcing a blockade of Cuba. Informed in

advance of the speech but not (until one hour before) the content,

Khrushchev and his advisors feared an invasion of Cuba. Even before

Kennedy's speech, they ordered Soviet commanders in Cuba that they

could use all weapons against an attack—except atomic weapons. As

the crisis unfolded, tensions were high in the US; less so in the

Soviet Union, where Khrushchev made several public appearances, and

went to the Bolshoi Theatre to hear American opera singer Jerome Hines, who was then performing in Moscow. By

October 25, with the Soviets unclear about Kennedy's full intentions,

Khrushchev decided that the missiles would have to be withdrawn from

Cuba. Two days later, he offered Kennedy terms for the withdrawal. Khrushchev agreed to withdraw the missiles in exchange for a US promise not to

invade Cuba and a promise that the US would withdraw missiles from

Turkey, near the Soviet heartland. As

the last term was not publicly announced at the request of the US, and

was not known until just before Khrushchev's death in 1971, the resolution was seen as a great defeat for the Soviets, and contributed to Khrushchev's fall less than two years later. After the crisis, superpower relations improved, as Kennedy gave a conciliatory speech at American University on June 10, 1963, recognizing the Soviet people's suffering during World War II, and paying tribute to their achievements. Khrushchev called the speech the best by a US president since Franklin Roosevelt, and, in July, negotiated a test ban treaty with US negotiator Averill Harriman and with Lord Hailsham of the United Kingdom. Plans

for a second Khrushchev-Kennedy summit were dashed by the US

President's assassination in November 1963. The new US President, Lyndon Johnson,

hoped for continued improved relations but was distracted by other

issues and had little opportunity to develop a relationship with

Khrushchev before the premier's ouster. The Secret Speech, combined with the death of Polish communist leader Boleslaw Bierut,

who suffered a heart attack while reading the Speech, sparked

considerable liberalization in Poland and Hungary. In Poland, a

worker's strike in Poznan developed into disturbances which

left more than 50 dead in October 1956. When Moscow blamed the

disturbances on Western agitators, Polish leaders ignored the claim,

and instead made concessions to the workers. With anti-Soviet displays

becoming more common in Poland, and crucial Polish leadership elections

upcoming, Khrushchev and other Presidium members flew to Warsaw. While

the Soviets were refused entry to the Polish Central Committee plenum

where the election was taking place, they met with the Polish

Presidium. The Soviets agreed to allow the new Polish leadership to

take office, on the assurance there would be no change to the

Soviet-Polish relationship. The Polish settlement emboldened the Hungarians, who decided that Moscow could be defied. A mass demonstration in Budapest on October 23 turned into a popular uprising. In response to the uprising, Hungarian Party leaders installed reformist Prime Minister Imre Nagy. Soviet

forces in the city clashed with Hungarians and even fired on

demonstrators, with hundreds of both Hungarians and Soviets killed.

Nagy called for a cease-fire and a withdrawal of Soviet troops, which a

Khrushchev-led majority in the Presidium decided to obey, choosing to

give the new Hungarian government a chance. Khrushchev

assumed that if Moscow announced liberalization in how it dealt with

its allies, Nagy would adhere to the alliance with the Soviet Union.

However, on October 30 Nagy announced multiparty elections, and the

next morning that Hungary would leave the Warsaw Pact. On

November 3, two members of the Nagy government appeared in Ukraine as

the self-proclaimed heads of a provisional government and demanded

Soviet intervention, which was forthcoming. The next day, Soviet troops

crushed the Hungarian uprising, with a death toll of 4,000 Hungarians

and several hundred Soviet troops. Nagy was arrested, and was later

executed. Despite the international outrage over the intervention,

Khrushchev defended his actions for the rest of his life. Damage to

Soviet foreign relations was severe, and would have been greater were

it not for the fortuitous timing of the Suez crisis, which distracted world attention. Khrushchev greatly improved relations with Yugoslavia, which had been entirely sundered in 1948 when Stalin realized he could not control Yugoslav leader Josip Tito.

Khrushchev led a Soviet delegation to Belgrade in 1955. Though a

hostile Tito did everything he could to make the Soviets look foolish

(including getting them drunk in public), Khrushchev was successful in

warming relations, ending the Informbiro period in Soviet-Yugoslav relations. During the Hungarian crisis, Tito initially supported Nagy, but Khrushchev persuaded him of the need for intervention. Still,

the intervention in Hungary damaged Moscow's relationship with

Belgrade, which Khrushchev spent several years trying to repair. He was

hampered by the fact that China disapproved of Yugoslavia's liberal

version of communism, and attempts to conciliate Belgrade resulted in

an angry Beijing. After completing his takeover of China in 1949, Mao Zedong sought material assistance from the USSR, and also called for the return to China of territories taken from it under the Czars. As

Khrushchev took control of the USSR, he increased aid to China, even

sending a small corps of experts to help develop the newly communist

country. The Soviet Union spent 7% of its national income between 1954 and 1959 on aid to China. On his 1954 visit to China, Khrushchev agreed to return Port Arthur and Dalian to China, though Khrushchev was annoyed by Mao's insistence that the Soviets leave their artillery as they departed. Mao bitterly opposed Khrushchev's attempts to reach a rapprochement with

more liberal Eastern European states such as Yugoslavia. Khrushchev's

government, on the other hand, was reluctant to endorse Mao's desires

for an assertive worldwide revolutionary movement, preferring to

conquer capitalism through raising the standard of living in

communist-bloc countries. Relations

between the two nations began to cool in 1956, with Mao angered both by

the Secret Speech and by the fact that the Chinese had not been

consulted in advance about it. Mao believed that de-Stalinization was a mistake, and a possible threat to his own authority. When Khrushchev visited Beijing in 1958, Mao refused proposals for military cooperation. Hoping to torpedo Khrushchev's efforts at détente with the US, Mao soon thereafter provoked the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis,

describing the Taiwanese islands shelled in the crisis as "batons that

keep Eisenhower and Khrushchev dancing, scurrying this way and that.

Don't you see how wonderful they are?" The

Soviets had planned to provide China with an atomic bomb complete with

full documentation, but in 1959, amid cooler relations, the Soviets

destroyed the device and papers instead. When

Khrushchev paid a visit to China in September, shortly after his

successful US visit, he met a chilly reception, and Khrushchev left the

country on the third day of a planned seven-day visit. Relations

continued to deteriorate in 1960, as both the USSR and China used a

Romanian Communist Party congress as an opportunity to attack the

other. After Khrushchev attacked China in his speech to the congress,

Chinese leader Peng Zhen mocked

Khrushchev, stating that the premier's foreign policy was to blow hot

and cold towards the West. Khrushchev responded by pulling Soviet

experts out of China. Beginning in March 1964, Supreme Soviet head Leonid Brezhnev began discussing Khrushchev's removal with his colleagues. While

Brezhnev considered having Khrushchev arrested as he returned from a

trip to Scandinavia in June, he instead spent time persuading members

of the Central Committee to support an ouster of Khrushchev,

remembering how crucial the Committee's support had been to Khrushchev

in defeating the Anti-Party Group plot. Brezhnev

was given ample time for his conspiracy; Khrushchev was absent from

Moscow for a total of five months between January and September 1964. The conspirators, led by Brezhnev, Aleksandr Shelepin, and KGB Chairman Vladimir Semichastny, struck in October 1964, while Khrushchev was on vacation at Pitsunda, Abkhazia.

On October 12, Brezhnev called Khrushchev to notify him of a special

Presidium meeting to be held the following day, ostensibly on the

subject of agriculture. Even though Khrushchev suspected the real reason for the meeting, he

flew to Moscow to be attacked by Brezhnev and other Presidium members

for his policy failures and what his colleagues deemed to be erratic

behavior. Khrushchev put up little resistance. On

October 14, 1964, the Presidium and the Central Committee each voted to

accept Khrushchev's "voluntary" retirement from his offices. Brezhnev

was elected First Secretary (later General Secretary), while Aleksei Kosygin succeeded Khrushchev as premier. Khrushchev was granted a pension of 500 rubles per month, and was assured that his house and dacha were his for life. Following his removal from power, Khrushchev fell into deep depression. He

received few visitors, especially since Khrushchev's security guards

kept track of all guests and reported their comings and goings. In the fall of 1965, he and his wife were ordered to leave their house and dacha to move to an apartment and to a smaller dacha. His pension was reduced to 400 rubles per month, though his retirement remained comfortable by Soviet standards. The

depression continued. He was made a nonperson to such an extent that the thirty-volume Soviet Encyclopedia omitted his name from the list of prominent political commissars during the Great Patriotic War. Beginning

in 1966, Khrushchev began his memoirs. He dictated them into a tape

recorder, and, after attempts to record outdoors failed due to

background noise, recorded indoors, knowing that every word would be

heard by the KGB. However, the security agency made no attempt to

interfere until 1968, when Khrushchev was ordered to turn over his

tapes, which he refused to do. However,

while Khrushchev was hospitalized with heart ailments his son, Sergei,

was approached by the KGB and told that there was a plot afoot by

foreign agents to steal the memoirs. Since copies had been made, some

of which had been transmitted to a Western publisher, and since the KGB

could steal the originals anyway, Sergei Khrushchev turned over the

materials to the KGB, but also instructed that the smuggled memoirs be

published, which they were in 1970 under the title Khrushchev Remembers.

Under some pressure, Nikita Khrushchev signed a statement that he had

not given the materials to any publisher, and his son was transferred

to a less desirable job. Upon publication of the memoirs in the West, Izvestia denounced them as a fraud. When

Soviet state radio carried the announcement of Khrushchev's statement,

it was the first time in six years he had been mentioned in that medium. Khrushchev died of a heart attack in a hospital near his home in Moscow on September 11, 1971, and is buried in the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow, having been denied a state funeral, and interment in the Kremlin Wall.

Fearing demonstrations, the authorities did not announce Khrushchev's

death until the hour of his wake, and surrounded the cemetery with

troops. Even so, some artists and writers joined the family at the

graveside for the interment. Pravda ran a one-sentence announcement of the former premier's death; Western newspapers contained considerable coverage. Veteran The New York Times Moscow

correspondent Harry Schwartz wrote of Khrushchev, "Mr.

Khrushchev opened the doors and windows of a petrified structure.

He let in fresh air and fresh ideas, producing changes which time

already has shown are irreversible and fundamental."