<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Ferdinand Gotthold Max Eisenstein, 1823

- Actor and Director Sir Charles Spencer "Charlie" Chaplin, 1889

- German Communist Politician Ernst Thälmann, 1886

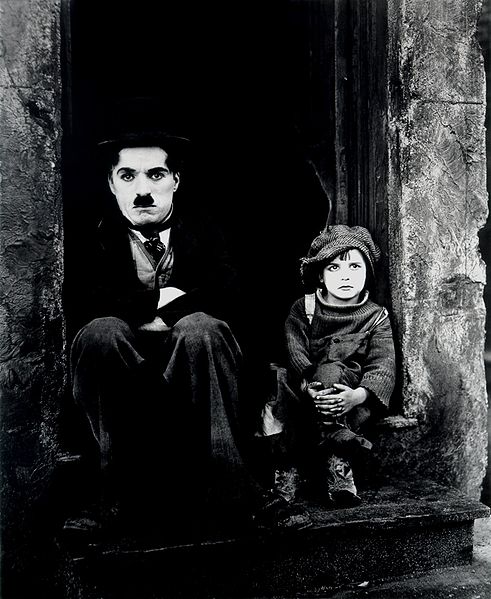

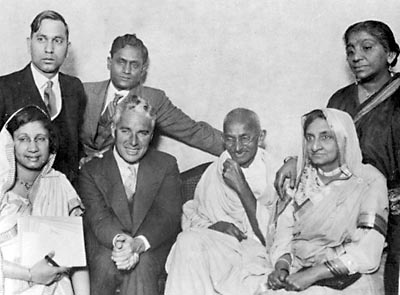

Sir Charles Spencer "Charlie" Chaplin, KBE (16 April 1889 – 25 December 1977) was an English comic actor and film director of the silent film era, and became one of the best known film stars in the world before the end of the First World War. Chaplin used mime, slapstick and other visual comedy routines, and continued well into the era of the talkies, though his films decreased in frequency from the end of the 1920s. His most famous role was that of The Tramp, which he first played in the Keystone comedy Kid Auto Races at Venice in 1914. From the April 1914 one-reeler Twenty Minutes of Love onwards he was writing and directing most of his films, by 1916 he was also producing, and from 1918 composing the music. With Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks and D.W. Griffith, he co-founded United Artists in 1919.

Chaplin

was one of the most creative and influential personalities of the

silent-film era. He was influenced by his predecessor, the French

silent movie comedian Max Linder, to whom he dedicated one of his films. His working life in entertainment spanned over 75 years, from the Victorian stage and the Music Hall in

the United Kingdom as a child performer almost until his death at the

age of 88. His high-profile public and private life encompassed both

adulation and controversy. Chaplin's identification with the left

ultimately forced him to resettle in Europe during the McCarthy era in the early 1950s. In 1999, the American Film Institute ranked Chaplin the 10th greatest male actor of all time. In 2008, Martin Sieff, in a review of the book Chaplin: A Life,

wrote: "Chaplin was not just 'big', he was gigantic. In 1915, he burst

onto a war-torn world bringing it the gift of comedy, laughter and

relief while it was tearing itself apart through the First World War.

Over the next 25 years, through the Great Depression and the rise of Hitler,

he stayed on the job. It is doubtful any individual has ever given more

entertainment, pleasure and relief to so many human beings when they

needed it the most". George Bernard Shaw called Chaplin "the only genius to come out of the movie industry". Charles Spencer Chaplin was born on 16 April 1889, in East Street, Walworth, London, England. His parents were both entertainers in the music hall tradition; his father, Charles Spencer Chaplin Sr, was a vocalist and an actor and his mother, Hannah Chaplin, a singer and an actress. They separated before Charlie was three. He learned singing from his parents. The 1891 census shows that his mother lived with Charlie and his older half-brother Sydney on Barlow Street, Walworth. As a small child, Chaplin also lived with his mother in various addresses in and around Kennington Road in Lambeth,

including 3 Pownall Terrace, Chester Street and 39 Methley Street. His

mother and maternal grandmother were from the Smith family of Romanichals, a fact of which he was extremely proud, though he described it in his autobiography as "the skeleton in our family cupboard". Chaplin's father, Charles Chaplin Sr., was an alcoholic and

had little contact with his son, though Chaplin and his half-brother

briefly lived with their father and his mistress, Louise, at 287

Kennington Road where a plaque now commemorates the fact. The

half-brothers lived there while their mentally ill mother lived at Cane Hill Asylum at Coulsdon. Chaplin's father's mistress sent the boy to Archbishop Temples Boys School. His father died of cirrhosis of the liver when Charlie was twelve in 1901. As of the 1901 Census, Charles resided at 94 Ferndale Road, Lambeth, as part of a troupe of young male dancers, The Eight Lancashire Lads, managed by a William Jackson. A larynx condition ended the singing career of Chaplin's mother. Hannah's first crisis came in 1894 when she was performing at The Canteen, a theatre in Aldershot.

The theatre was mainly frequented by rioters and soldiers. Hannah was

injured by the objects the audience threw at her and she was booed off

the stage. Backstage, she cried and argued with her manager. Meanwhile,

the five-year old Chaplin went on stage alone and sang a well-known

tune at that time, "Jack Jones." After

Chaplin's mother (who went by the stage name Lilly Harley) was again

admitted to the Cane Hill Asylum, her son was left in the workhouse at Lambeth in south London, moving after several weeks to the Central London District School for paupers in Hanwell.

The young Chaplin brothers forged a close relationship in order to

survive. They gravitated to the Music Hall while still very young, and

both of them proved to have considerable natural stage talent.

Chaplin's early years of desperate poverty were a great influence on

his characters. Themes in his films in later years would re-visit the

scenes of his childhood deprivation in Lambeth. Chaplin's

mother died in 1928 in Hollywood, seven years after having been brought

to the U.S. by her sons. Unknown to Charlie and Sydney until years

later, they had a half-brother through their mother. The boy, Wheeler Dryden (1892–1957), was raised abroad by his father but later connected with the rest of the family and went to work for Chaplin at his Hollywood studio. Chaplin first toured the United States with the Fred Karno troupe

from 1910 to 1912. After five months back in England, he returned to

the U.S. for a second tour, arriving with the Karno Troupe on 2 October

1912. In the Karno Company was Arthur Stanley Jefferson, who later

became known as Stan Laurel.

Chaplin and Laurel shared a room in a boarding house. Stan Laurel

returned to England but Chaplin remained in the United States. In late

1913, Chaplin's act with the Karno Troupe was seen by Mack Sennett, Mabel Normand, Minta Durfee, and Fatty Arbuckle. Sennett hired him for his studio, the Keystone Film Company as a replacement for Ford Sterling. Chaplin

had considerable initial difficulty adjusting to the demands of film

acting and his performance suffered for it. After Chaplin's first film

appearance, Making a Living was filmed, Sennett felt he had made a costly mistake. Most historians agree it was Normand who persuaded him to give Chaplin another chance. Chaplin was given over to Normand, who directed and wrote a handful of his earliest films. Chaplin did not enjoy being directed by a woman, and they often disagreed. Eventually,

the two worked out their differences and remained friends long after

Chaplin left Keystone. The Tramp debuted during the silent film era in

the Keystone comedy Kid Auto Races at Venice (released

on 7 February 1914). Chaplin, with his Little Tramp character, quickly

became the most popular star in Keystone director Mack Sennett's

company of players. Chaplin continued to play the Tramp through dozens

of short films and, later, feature-length productions (in only a

handful of other productions did he play characters other than the

Tramp). The

Tramp was closely identified with the silent era, and was considered an

international character; when the sound era began in the late 1920s,

Chaplin refused to make a talkie featuring the character. The 1931

production City Lights featured no dialogue. Chaplin officially retired the character in the film Modern Times (5 February 1936), which appropriately ended with the Tramp walking down

an endless highway toward the horizon. Two films Chaplin made in 1915, The Tramp and The Bank,

created the characteristics of his screen persona. While in the end the

Tramp manages to shake off his disappointment and resume his carefree

ways, “the pathos lies in The Tramp's hope for a more permanent

transformation through love, and his failure to achieve this.” "The Tramp" is a vagrant with the refined manners, clothes, and dignity of a gentleman. "Fatty" Arbuckle contributed his father-in-law's derby and his own pants (of generous proportions). Chester Conklin provided the little cutaway tailcoat, and Ford Sterling the

size-14 shoes, which were so big, Chaplin had to wear each on the wrong

foot to keep them on. He devised the moustache from a bit of crepe hair

belonging to Mack Swain. The only thing Chaplin himself owned was the whangee cane. Chaplin's tramp character would immediately gain enormous popularity among cinema audiences. "The Tramp", Chaplin's principal character, was known as "Charlot" in the French-speaking world, Italy, Spain, Andorra, Portugal, Greece, Romania and Turkey, "Carlitos" in Brazil and Argentina, and "Der Vagabund" in Germany. Chaplin's early Keystones use the standard Mack Sennett formula of extreme physical comedy and

exaggerated gestures. Chaplin's pantomime was subtler, more suitable to

romantic and domestic farces than to the usual Keystone chases and mob

scenes. The visual gags were pure Keystone, however; the tramp

character would aggressively assault his enemies with kicks and bricks.

Moviegoers loved this cheerfully earthy new comedian, even though

critics warned that his antics bordered on vulgarity. Chaplin was soon

entrusted with directing and editing his own films. He made 34 shorts

for Sennett during his first year in pictures, as well as the landmark

comedy feature Tillie's Punctured Romance. The

Tramp character was featured in the first movie trailer to be exhibited

in a U.S. movie theater, a slide promotion developed by Nils Granlund, advertising manager for the Marcus Loew theater chain, and shown at the Loew's Seventh Avenue Theatre in Harlem in 1914. In 1915, Chaplin signed a much more favorable contract with Essanay Studios,

and further developed his cinematic skills, adding new levels of depth

and pathos to the Keystone-style slapstick. Most of the Essanay films

were more ambitious, running twice as long as the average Keystone

comedy. Chaplin also developed his own stock company, including ingénue Edna Purviance and comic villains Leo White and Bud Jamison. As

new immigrant groups arrived in waves to America silent movies were

able to cross all the barriers of language, and spoke to every level of

the American Tower of Babel,

precisely because they were silent. Chaplin was emerging as the supreme

exponent of silent movies, an emigrant himself from London. Chaplin's

Tramp enacted the difficulties and humiliations of the immigrant underdog,

the constant struggle at the bottom of the American heap and yet he

triumphed over adversity without ever rising to the top, and thereby

stayed in touch with his audience. Chaplin's films were also

deliciously subversive. The bumbling officials enabled the immigrants

to laugh at those they feared. In 1916, the Mutual Film Corporation paid

Chaplin US$670,000 to produce a dozen two-reel comedies. He was given

near complete artistic control, and produced twelve films over an

eighteen-month period that rank among the most influential comedy films

in all cinema. Practically every Mutual comedy is a classic: Easy Street, One AM, The Pawnshop, and The Adventurer are perhaps the best known. Edna Purviance remained the leading lady, and Chaplin added Eric Campbell, Henry Bergman, and Albert Austin to his stock company; Campbell, a Gilbert and Sullivan veteran,

provided superb villainy, and second bananas Bergman and Austin would

remain with Chaplin for decades. Chaplin regarded the Mutual period as

the happiest of his career, although he also had concerns that the

films during that time were becoming formulaic owing to the stringent

production schedule his contract required. Upon the U.S. entering World

War I, Chaplin became a spokesman for Liberty Bonds with his close

friend Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford. At the conclusion of the Mutual contract in 1917, Chaplin signed a contract with First National to

produce eight two-reel films. First National financed and distributed

these pictures (1918–23) but otherwise gave him complete creative

control over production. Chaplin now had his own studio, and he could

work at a more relaxed pace that allowed him to focus on quality.

Although First National expected Chaplin to deliver short comedies like

the celebrated Mutuals, Chaplin ambitiously expanded most of his

personal projects into longer, feature-length films, including Shoulder Arms (1918), The Pilgrim (1923) and the feature-length classic The Kid (1921). In 1919, Chaplin co-founded the United Artists film distribution company with Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks and D. W. Griffith,

all of whom were seeking to escape the growing power consolidation of

film distributors and financiers in the developing Hollywood studio system.

This move, along with complete control of his film production through

his studio, assured Chaplin's independence as a film-maker. He served

on the board of UA until the early 1950s. All

Chaplin's United Artists pictures were of feature length, beginning

with the atypical drama in which Chaplin had only a brief cameo role, A Woman of Paris (1923). This was followed by the classic comedies The Gold Rush (1925) and The Circus (1928). After the arrival of sound films, Chaplin made The Circus (1928), City Lights (1931), as well as Modern Times (1936) before he committed to talking pictures. These were essentially silent films scored with his own music and sound effects. City Lights contained arguably his most perfect balance of comedy and sentimentality. While Modern Times (1936)

is a non-talkie, it does contain talk—usually coming from inanimate

objects such as a radio or a TV monitor. This was done to help 1930s

audiences, who were out of the habit of watching silent films, adjust

to not hearing dialogue. Modern Times was the first film where Chaplin's voice is heard (in the nonsense song at the end, being both written and performed by Chaplin). However, for most viewers it is still considered a silent film. It is a tribute to Chaplin's versatility that he also has one film credit for choreography for the 1952 film Limelight, and another as a singer for the title music of The Circus (1928). The best known of several songs he composed are "Smile", composed for the film Modern Times (1936) and given lyrics to help promote a 1950s revival of the film, famously covered by Nat King Cole. This Is My Song from Chaplin's last film, A Countess from Hong Kong, was a number one hit in several different languages in the late 1960s (most notably the version by Petula Clark and discovery of an unreleased version in the 1990s recorded in 1967 by Judith Durham of The Seekers), and Chaplin's theme from Limelight was a hit in the 1950s under the title "Eternally." Chaplin's score to Limelight won an Academy Award in

1972; a delay in the film premiering in Los Angeles made it eligible

decades after it was filmed. Chaplin also wrote scores for his earlier

silent films when they were re-released in the sound era, notably The Kid for its 1971 re-release. Chaplin's first talking picture, The Great Dictator (1940), was an act of defiance against Nazism, filmed and released in the United States one year before the U.S. abandoned its policy of neutrality to enter World War II. Chaplin played the role of "Adenoid Hynkel", Dictator of Tomania, modeled on German dictator Adolf Hitler. The film also showcased comedian Jack Oakie as "Benzino Napaloni", dictator of Bacteria, a jab at Italian dictator Benito Mussolini. Paulette Goddard filmed

with Chaplin again, depicting a woman in the ghetto. The film was seen

as an act of courage in the political environment of the time, both for

its ridicule of Nazism and for the portrayal of overt Jewish characters

and the depiction of their persecution. In addition to Hynkel, Chaplin

also played a look-alike Jewish barber persecuted by his regime, who

physically resembled the Tramp character. At the conclusion, the two

characters Chaplin portrayed swapped positions through a complex plot,

and he dropped out of his comic character to address the audience

directly in a speech. He was nominated for Academy awards for Best Picture (producer), Best Original Screenplay (writer) and Best Actor in The Great Dictator.

Chaplin's political sympathies always lay with the left. His silent films made prior to the Great Depression typically did not contain overt political themes or messages, apart from the Tramp's plight in poverty and his run-ins with the law, but his 1930s films were more openly political. Modern Times depicts workers and poor people in dismal conditions. The final dramatic speech in The Great Dictator,

which was critical of following patriotic nationalism without question,

and his vocal public support for the opening of a second European front

in 1942 to assist the Soviet Union in World War II were controversial. Chaplin declined to support the war effort as he had done for the First World War which

led to public anger, although his two sons saw service in the Army in

Europe. For most of World War II he was fighting serious criminal and

civil charges related to his involvement with actress Joan Barry. After the war, his 1947 black comedy Monsieur Verdoux showed a critical view of capitalism. Chaplin's final American film, Limelight, was less political and more autobiographical in nature. His following European-made film, A King in New York (1957), satirized the political persecution and paranoia that had forced him to leave the U.S. five years earlier. Although

Chaplin had his major successes in the United States and was a resident

from 1914 to 1953, he always maintained a neutral nationalistic stance.

During the era of McCarthyism, Chaplin was accused of "un-American activities" as a suspected communist and J. Edgar Hoover, who had instructed the FBI to

keep extensive secret files on him, tried to end his United States

residency. FBI pressure on Chaplin grew after his 1942 campaign for a

second European front in the war and reached a critical level in the

late 1940s, when Congressional figures threatened to call him as a

witness in hearings. This was never done, probably from fear of

Chaplin's ability to lampoon the investigators. In 1952, Chaplin left the US for what was intended as a brief trip home to the United Kingdom for the London premiere of Limelight. Hoover learned of the trip and negotiated with the Immigration and Naturalization Service to

revoke Chaplin's re-entry permit, exiling Chaplin so he could not

return for his alleged political leanings. Chaplin decided not to

re-enter the United States, writing; ".....Since the end of the last

world war, I have been the object of lies and propaganda by powerful reactionary groups who, by their influence and by the aid of America's yellow press,

have created an unhealthy atmosphere in which liberal-minded

individuals can be singled out and persecuted. Under these conditions I

find it virtually impossible to continue my motion-picture work, and I

have therefore given up my residence in the United States." Chaplin then made his home in Vevey, Switzerland. He briefly and triumphantly returned to the United States in April 1972, with his wife, to receive an Honorary Oscar, and also to discuss how his films would be re-released and marketed. Chaplin's final two films were made in London: A King in New York (1957) in which he starred, wrote, directed and produced; and A Countess from Hong Kong (1967), which he directed, produced, and wrote. The latter film stars Sophia Loren and Marlon Brando,

and Chaplin made his final on-screen appearance in a brief cameo role

as a seasick steward. He also composed the music for both films with

the theme song from A Countess From Hong Kong, "This is My Song," reaching number one in the UK as sung by Petula Clark. Chaplin also compiled a film The Chaplin Revue from three First National films A Dog's Life (1918), Shoulder Arms (1918) and The Pilgrim (1923)

for which he composed the music and recorded an introductory narration.

As well as directing these final films, Chaplin also wrote My Autobiography, between 1959 and 1963, which was published in 1964. In his pictorial autobiography My Life In Pictures, published in 1974, Chaplin indicated that he had written a screenplay for his daughter, Victoria; entitled The Freak,

the film would have cast her as an angel. According to Chaplin, a

script was completed and pre-production rehearsals had begun on the

film (the book includes a photograph of Victoria in costume), but were

halted when Victoria married. "I mean to make it some day," Chaplin

wrote. However, his health declined steadily in the 1970s which

hampered all hopes of the film ever being produced. From

1969 until 1976, Chaplin wrote original music compositions and scores

for his silent pictures and re-released them. He composed the scores of

all his First National shorts: The Idle Class in 1971 (paired with The Kid for re-release in 1972), A Day's Pleasure in 1973, Pay Day in 1972, Sunnyside in 1974, and of his feature length films firstly The Circus in 1969 and The Kid in 1971. Chaplin worked with music associate Eric James whilst composing all his scores. Chaplin's last completed work was the score for his 1923 film A Woman of Paris, which was completed in 1976, by which time Chaplin was extremely frail, even finding communication difficult. Chaplin's robust health began to slowly fail in the late 1960s, after the completion of his final film A Countess from Hong Kong,

and more rapidly after he received his Academy Award in 1972. By 1977,

he had difficulty communicating, and was using a wheelchair. Chaplin

died in his sleep in Vevey, Switzerland on Christmas Day 1977. Chaplin was interred in Corsier-Sur-Vevey Cemetery, Vaud, Switzerland. On 1 March 1978, his corpse was stolen by a small group of Swiss mechanics in an attempt to extort money from his family. The plot failed, the robbers were captured, and the corpse was recovered eleven weeks later near Lake Geneva. His body was reburied under 6 feet (1.8 m) of concrete to prevent further attempts.