<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Lars Valerian Ahlfors, 1907

- Architect Jan Kaplický, 1937

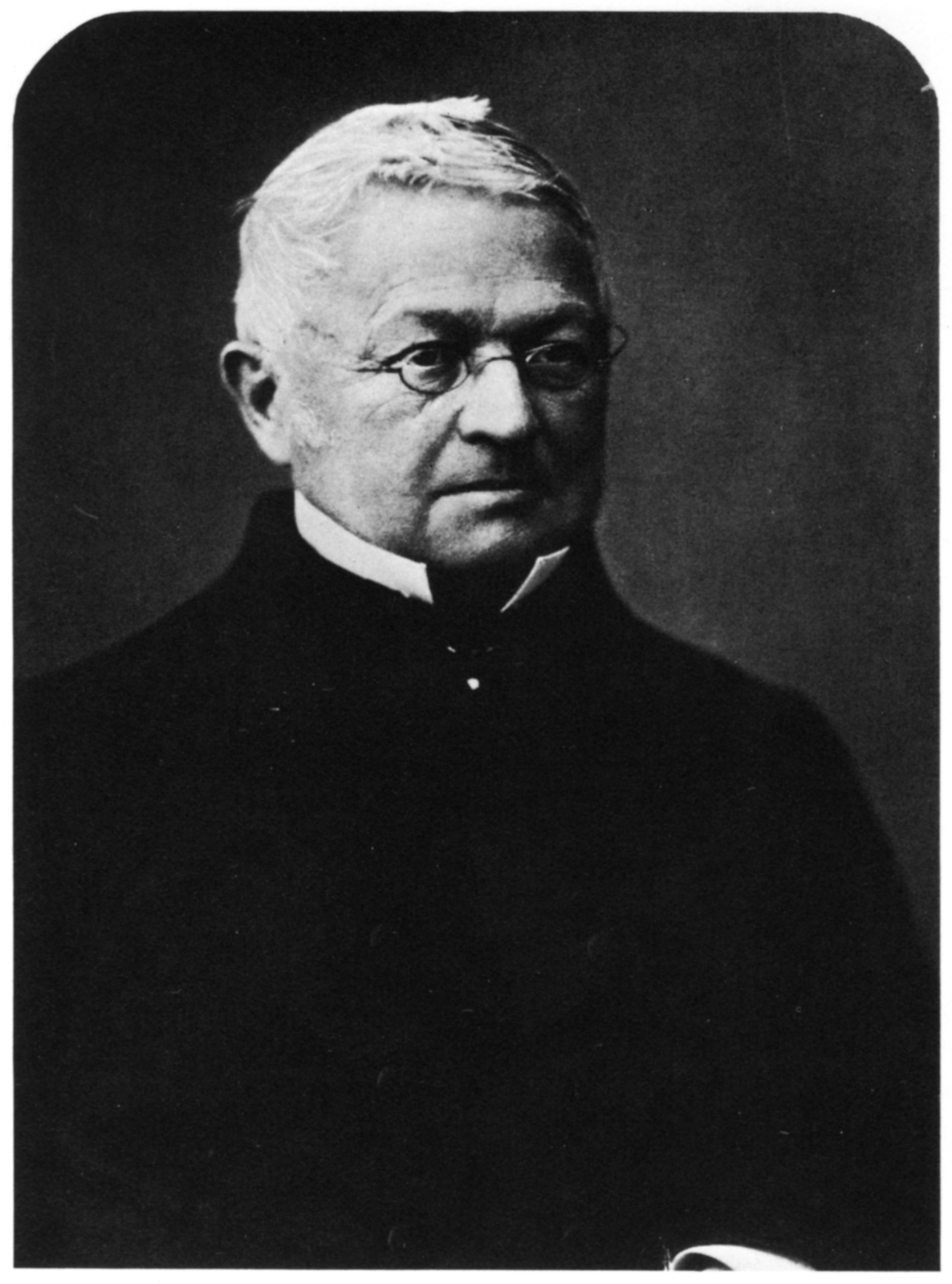

- Président de la République Française Louis-Adolphe Thiers, 1797

Louis-Adolphe Thiers (Marseille, 18 April 1797–3 September 1877) was a French politician and historian. Thiers was a prime minister under King Louis-Philippe of France. Following the overthrow of the Second Empire he again came to prominence as the French leader who suppressed the revolutionary Paris Commune of 1871. From 1871 to 1873 he served initially as Head of State (effectively a provisional President of France), then provisional President. When, following a vote of no confidence in the National Assembly, his offer of resignation was accepted (he had expected a rejection) he was forced to vacate the office. He was replaced as Provisional President by Patrice MacMahon, duc de Magenta, who became full President of the Republic, a post Thiers had coveted, in 1875 when a series of constitutional laws officially creating the Third Republic were enacted.

Thiers's maternal grandmother was the sister of Élisabeth Santi-Lomaca, mother of André Chénier, of Greek origins. His family was somewhat grandiloquently spoken of as "cloth merchants ruined by the Revolution", but it seems that at the actual time of his birth his father was a locksmith. His mother belonged to the family of the Chéniers, and he was well educated, first at the lycée of Marseille, and then in the faculty of law at Aix-en-Provence. Here he began his lifelong friendship with Mignet, and was called to the bar at the age of twenty-three. He had, however, little taste for law and much for literature; and he obtained an academic prize at Aix for a discourse on the marquis de Vauvenargues. In the early autumn of 1821 Thiers went to Paris, and was quickly introduced as a contributor to the Le Constitutionnel. In each of the years immediately following his arrival in Paris he collected and published a volume of his articles, the first on the salon of 1822, the second on a tour in the Pyrenees. He was put out of all need of money by the singular benefaction of Cotta, the well-known Stuttgart publisher, who was part-proprietor of the Constitutionnel, and made over to Thiers his dividends, or part of them.

Meanwhile, he became very well known in Liberal society, and he had begun the celebrated Histoire de la revolution française,

which founded his literary and helped his political fame. The first two

volumes appeared in 1823, the last two (of ten) in 1827. The book

brought him little profit at first, but became immensely popular. The

well-known sentence of Carlyle, that it is "as far as possible from meriting its high reputation", is in strictness justified, for all Thiers'

historical work is marked by extreme inaccuracy, by prejudice which

passes the limits of accidental unfairness, and by an almost complete

indifference to the merits as compared with the successes of his

heroes. But Carlyle himself admits that Thiers is

"a brisk man in his way, and will tell you much if you know nothing."

Coming as the book did just when the reaction against the Revolution

was about to turn into another reaction in its favour, it was assured

of success. For a moment it seemed as if Thiers had definitely chosen the lot of a literary man, not to say of a literary hack. He even planned an Histoire générale. But the accession to power of the Polignac ministry in August 1829 made him change his plans, and at the beginning of the next year Thiers, with Armand Carrel, Mignet, Sautelet and others started the National, a new opposition newspaper. Thiers himself

was one of the animators of the 1830 revolution, being credited with

"overcoming the scruples of Louis Philippe," perhaps no Herculean task.

At any rate, he received his reward. He ranked as one of the Radical

supporters of the new dynasty, in opposition to the party of which his

rival François Guizot was the chief literary man, and Guizot's patron, the duc de Broglie, the main pillar. At first Thiers, though elected deputy for Aix, received only subordinate posts in the ministry of finance. After the overthrow of his patron Jacques Laffitte,

he became much less radical, and after the troubles of June 1832 he was

appointed to the ministry of the interior. He repeatedly changed

portfolios, but remained in office for four years, became president of

the council and, in effect, Prime Minister,

in which capacity he began his series of quarrels and jealousies with

Guizot. After 1833, his career was bolstered by his marriage, as he

secured financial backing from his nouveau riche patrons (in exchange for their place in the state officialdom and high society). At the time of his resignation in 1836 he was foreign minister and, as usual, favoured an energetic policy toward Spain, which he could not carry out. He travelled in Italy for some time, and it was not till 1838 that he began a regular campaign of parliamentary opposition,

which in March 1840 made him president of the council and foreign

minister for the second time, during which time he initiated the return of Napoleon's remains to France in 1840. His policy of support for Muhammad Ali of Egypt in

the Eastern crisis of that year led France to the brink of war with the

other great powers. This resulted in his dismissal by the king, who did

not wish for war. Thiers now had little to do with politics for some years, and spent his time on his Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, the first volume of which appeared in 1845. Though

he was still a member of the chamber, he spoke rarely, till after the

beginning of 1846, when he was evidently bidding once more for power as

the leader of the opposition group of the Center-Left. He then became a

liberal opponent of the July Monarchy and again turned to writing,

beginning his History of the Consulate and the Empire (20 vol.,

1845–62; tr. 1845–62). In the midst of the February Revolution of 1848,

Louis Philippe offered him the title of premier, but he refused, and

both king and Thiers were soon swept aside by the revolutionary tide.

Elected (1848) to the constituent assembly, Thiers was a leader of the

right-wing liberals and bitterly opposed the socialists. Immediately

before the February revolution he went to all but the greatest lengths,

and when it broke out he and Odilon Barrot, the leader of the Dynastic Left, were summoned by the king; but it was too late. Thiers was unable to govern the forces he had helped to gather, and he resigned. Under

the Republic he took up the position of conservative republican, which

he ever afterwards maintained, and he never took office. But the

consistency of his conduct, especially in voting for Louis Napoleon as president, was often and sharply criticized, one of the criticisms leading to a duel with a fellow-deputy, Bixio. He had an important role in the shaping of the Falloux Laws of 1850, which strongly increased the Catholic clergy's influence on the education system. Thiers was then arrested during the December 1851 coup d'état and sent to the prison of Mazas,

before being escorted out of France. But in the following summer he was

allowed to return. His history for the next decade is almost a blank,

his time being occupied for the most part on The Consulate and the Empire.

It was not until 1863 that he re-entered political life, being elected

by a Parisian constituency. For the seven years following he was the

chief speaker among the small group of anti-Imperialists in the French

chamber and was regarded generally as the most formidable enemy of the

Empire. While protesting against its foreign enterprises, he also

harped on French loss of prestige, and so helped contribute to stir up

the fatal spirit which brought on the war of 1870. In the diplomatic crisis of 1870, Thiers was one of the few who strongly opposed war with Prussia, and was accused of lack of patriotism. But when France's armies suffered defeat after defeat in the Franco-Prussian War (all within a period of a few weeks), Thiers's earlier stance was vindicated. He urged early peace negotiations, and refused to take part in the new republican Government of National Defense, which was determined to continue the war. In

the latter part of September and the first three weeks of October, 1870

he went on a tour of Britain, Italy, Austria and Russia in the hope of

obtaining an intervention, or at least some mediation. The mission was

unsuccessful, as was his attempt to persuade Prussian chancellor Otto

von Bismarck and the Government of National Defence to negotiate. When the French government was finally forced to surrender, Thiers triumphantly

re-entered the political scene. In national elections, he was elected

in twenty-six departments; on 17 February 1871 Thiers was

elected head of a provisional government, nominally "chef du pouvoir

exécutif de la République en attendant qu'il soit

statué sur les institutions de la France" (head of the executive power of the Republic until the institutions of France are decided).

He succeeded in convincing the deputies that the peace was necessary,

and on 1 March 1871 it was voted for by a margin of more than five to

one. On 18 March, a major insurrection began in Paris after Thiers ordered the army to remove several hundred cannons in the possession of the Paris National Guard. Thiers evacuated

his government and troops to Versailles. Parisians elected a radical

republican and socialist city government on 26 March entitled the Paris Commune. Fighting

broke out between government troops and those of the Commune early

in April. Neither side was willing to negotiate, and fighting continued

throughout April and May in the city's suburbs. On 21 May, government

forces broke through the city's defences, and a week of street

fighting, known as 'la Semaine Sanglante' (Bloody Week) began.

Thousands of Parisians were killed in the fighting or summarily

executed by courts martial. Thiers has

often been accused of ordering this massacre – probably the worst in

Europe between the French Revolution and the Russian Revolution of 1917

– but more likely he washed his hands of a massacre carried out by the

army, thinking that it was a 'lesson' that the insurgents deserved. Thiers insisted

on using legal means to prosecute the thousands of prisoners taken by

the army, and over 12,000 were tried by special courts martial; of

these 23 were executed, and over 4,000 transported to New Caledonia, from where the last prisoners were amnestied in 1880. This severe repression has always been blamed principally on Thiers, and has overshadowed his memory in France and more generally on the political Left. On 30 August Thiers became

the provisional president of the as-yet undeclared republic. He held

office for more than two years after this event. Thiers was the only French President born in the 18th century. His two predecessors – Emperor Napoleon III (who served previously as President of the 2nd Republic from 1848 to 1854), and Interim President Louis Jules Trochu were born in the 19th century (Bonaparte in 1808 and Trochu in 1825). His

strong personal will and inflexible opinions had much to do with the

resurrection of France; but the very same facts made it inevitable that

he should excite violent opposition. He was a confirmed protectionist, and free trade ideas had made great headway in France under the Empire; he was an advocate of long military service, and the devotees of la revanche (the

revenge) were all for the introduction of general and compulsory but

short service. Both his talents and his temper made him utterly

indisposed to maintain the attitude supposed to be incumbent on a

republican president; and his tongue was never carefully governed. In

January 1872 he formally tendered his resignation; and though it was

refused, almost all parties disliked him, while his chief supporters,

men like Charles de Rémusat, Jules Barthélemy-Saint-Hilaire and Jules Simon were men rather of the past than of the present.

The year 1873, a parliamentary year in France, was occupied to a great extent with attacks on Thiers, essentially by the royalist majority in the National Assembly, who suspected, correctly, that Thiers was

putting the weight of his enormous popularity among the electorate at

the service of a future republic, which he famously described as 'the

government that divides us least'. In the early spring, regulations

were proposed and, on 13 April, carried, intended to restrict the

executive, and especially the parliamentary, powers of the president,

who was no longer to be allowed to speak in the Assembly. On 27 April a

contested election in Paris, resulting in the return of a radical

republican candidate, Barodet, was regarded as a grave disaster for the Thiers government,

because it convinced the royalists that France was moving too far to

the Left. The principal royalist leader, the Duc de Broglie, proposed a

motion of no confidence in the government, which was carried by sixteen

votes in a house of 704. Thiers at

once resigned (24 May), expecting that he would have his resignation

rescinded or that he would be immediately re-elected. To his shock the

resignation was accepted and a professional soldier, Marshal Patrice de

MacMahon, was elected to the provisional presidency instead. He survived, after his fall, for four years, continuing to sit in the Assembly and, after the dissolution of 1876, in the Chamber of Deputies, and sometimes, though rarely, speaking. He was also, on the occasion of this dissolution, elected senator for Belfort,

which his exertions had saved for France; but he preferred the lower

house, where he sat as of old for Paris. On 16 May 1877, he was one of

the "363" who voted for no confidence in the Broglie ministry (thus

paying his debts), and he took a considerable part in organizing the

subsequent electoral campaign as an ally of the Republicans. But he was not to see its success, suffering a fatal stroke at St. Germain-en-Laye on 3 September. Thiers was buried in Cimetière du Père Lachaise,

an ironic resting place since one of the bloodiest battles of the

Commune took place within the cemetery walls. Annually, the French Left holds a ceremony at the Communards' Wall to mark the anniversary of the occasion. Thiers' tomb has occasionally been the object of vandalism.