<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Oscar Zariski, 1899

- Architect John Russell Pope, 1874

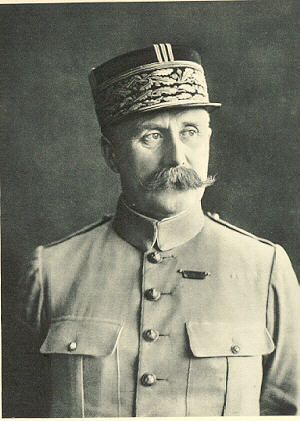

- Chef de l' État Français Philippe Pétain, 1856

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Joseph Pétain (24 April 1856 – 23 July 1951), generally known as Philippe Pétain or Marshal Pétain (Maréchal Pétain), was a French general who reached the distinction of Marshal of France, and was later Chief of State of Vichy France (Chef de l'État Français), from 1940 to 1944. Pétain, who was 84 years old in 1940, ranks as France's oldest head of state.

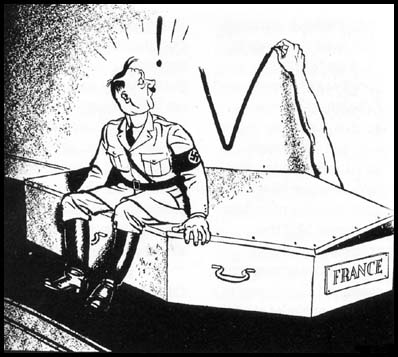

Because of his outstanding military leadership in World War I, particularly during the Battle of Verdun, he was viewed as a hero in France. However, as the highest ranking military authority of the 1920s and 1930s, he did not modernize the French military except for the Maginot Line. After the French defeat in June 1940, Pétain was legally voted in as Head of State (Chef de l'Etat) by the French Parliament to make peace with Germany. Along with his cabinet, which later included Pierre Laval, he transformed the French Republic into the French State, an authoritarian régime administered from the town of Vichy in central France. As the war progressed, the Vichy Government collaborated more closely with the Germans, who in 1943 finally occupied the whole of metropolitan France. Petain's actions during World War II resulted in a conviction and death sentence for treason, which was commuted to life imprisonment by his former protegé Charles de Gaulle. In modern France he is remembered as an ambiguous figure while pétainisme is a derogatory term for certain reactionary policies.

Pétain was born in Cauchy-à-la-Tour (in the Pas-de-Calais département in the north of France) in 1856. He joined the French Army in 1876 and attended the St Cyr Military Academy in 1887 and the École Supérieure de Guerre (army war college) in Paris. His career progressed very slowly, as he rejected the French Army philosophy

of the furious infantry assault, arguing instead that "firepower

kills". His views were later proved to be correct during the First

World War. He was promoted to Captain in 1890 and Major (Chef de

Bataillon) in 1900, but unlike many French officers, served only in

mainland France, never in Africa or Indochina. As a Colonel he commanded the 33rd Infantry Regiment at Arras from 1911; the young lieutenant Charles de Gaulle,

who served under him, later wrote that his "first colonel,

Pétain, taught (him) the Art of Command".

In the spring of 1914

he was given command of a brigade (still with the rank of Colonel),

but having been told he would never become a general, had bought a

house pending retirement - he was already fifty-eight years old. Pétain distinguished himself in World War I, and was hailed as a French hero and the "Saviour of Verdun". At the end of August 1914 he was quickly promoted to Brigadier-General and given command of the 6th Division in time for the First Battle of the Marne;

little over a month later, in October 1914, he was promoted again and

became XXXIII Corps commander. After leading his corps in the Spring

1915 Artois Offensive, in July 1915 he was given command of the Second Army,

which he led in the Champagne Offensive that autumn. He acquired a

reputation as one of the more successful commanders on the Western

Front. Pétain commanded the Second Army at the start of the Battle of Verdun in

February 1916. During the battle he was promoted to Commander of Army

Group Centre, which contained a total of 52 divisions. Rather than

holding down the same infantry divisions on the Verdun battlefield for

months, akin to the German system, he rotated them out after only two

weeks on the front lines. His decision to organize truck transport over

the "Voie Sacrée"

to bring a continuous stream of artillery, ammunition and fresh troops

into besieged Verdun also played a key role in grinding down the German

onslaught to a final halt in July 1916. In effect he had applied the

basic principle that was a mainstay of his teachings at the

"École de Guerre" (War College) before World War I: "le feu tue !"

or "firepower kills!" which in this case was French field artillery

which delivered well over 15 million shells on the German assailants

during the first five months of the battle. Although Pétain did

say "On les aura!" (roughly: We'll get them!), the other famous quotation "Ils ne passeront pas!" (They shall not pass!) often attributed to him, is actually from Robert Nivelle, who had succeeded him in command of the Second Army at Verdun. At the very end of 1916, Nivelle was promoted over him to replace Joseph Joffre as French Commander-in-Chief. Because

of his high prestige as a soldier's soldier, Pétain served

briefly as Army Chief of Staff (from the end of April 1917). He then

became Commander-in-Chief of the French army, replacing General Nivelle, whose Chemin des Dames offensive

failed in April 1917 thereby provoking widespread mutinies in the

French Army. Pétain put an end to the mutinies by selective

punishment of ringleaders, but also by improving soldiers' conditions

(e.g., better food and shelter, and more leaves to visit their

families), and promising that men's lives would not be squandered in

fruitless offensives. Pétain conducted some successful but

limited offensives in the latter part of 1917, unlike the British who

had stalled in an unsuccessful offensive at Passchendaele that autumn.

Pétain, instead, held off from major French offensives until the

Americans arrived in force on the front lines, which would not happen

until the early summer of 1918. He was also waiting for the new Renault FT17 tanks to be introduced in large numbers, hence his statement at the time: "I am waiting for the tanks and the Americans". The

year 1918 saw major German offensives on the Western Front. The first

of these, "Michael" in March 1918, threatened to split the British and

French forces apart, and, after he had threatened to retreat on Paris,

Pétain came to the aid of the British and secured the Front with

forty French divisions. Petain proved a capable opponent of the Germans

both in defense and through counter-attack. The crisis led to the appointment of Ferdinand Foch as

Allied Generalissimo, initially with powers to co-ordinate and deploy

Allied reserves where he saw fit. The third offensive, "Blücher"

in May 1918, saw major German advances on the Aisne,

as the French Army Commander (Humbert) had ignored Pétain's

instructions to defend in depth, and had instead allowed his men to be

hit by the initial massive German bombardment. By the time of the last German offensives, Gneisenau and the Second Battle of the Marne,

Pétain was able to defend in depth and launch counter

offensives, with the new French tanks and the assistance of the

Americans. Later

in the year Pétain was stripped of his right of appeal to the

French Government, and told to take his orders from Foch, who

increasingly assumed the co-ordination and ultimately the command of

the Allied offensives. Pétain

was a bachelor until his sixties, and famous for his womanising - women

were said to find his piercing blue eyes especially attractive. At the

opening of the Battle of Verdun he is said to have been fetched during

the night from a Paris hotel by a staff officer who knew which mistress

he could be found with. After the war Pétain married an old

lover, Madame Eugénie Hardon (1877–1962), on 14 September 1920. Hardon was divorced from François de Hérain in 1914; although the couple were too old to have children (she had a son, Pierre de Hérain, from her first marriage), they remained married until the end of Pétain's life. Pétain

emerged from the war as a national hero and was made a Marshal of

France. He was encouraged to go into politics although he protested

that he had little interest in running for an elected position. He

continued to play a military role, commanding French troops during

their alliance with the Spanish in the Rif War after 1925. Pétain is also on record as a strong supporter of the Maginot Line which

proved to be exceedingly costly while geographically limited and thus a

strategically ineffective border defense. Pétain had based his

strong support for the Maginot Line on his own experience of the role

played by the forts during the Battle of Verdun in 1916. Captain Charles de Gaulle continued

to be a protégé of Pétain throughout these years.

He even named his eldest son after the Marshal before finally falling

out over the authorship of a book he had ghost-written for

Pétain. In later years, in a reference to the Rif War, de Gaulle had been known to observe: "Marshal Pétain was a great

man; he died in 1925". Pétain finally retired as Inspector-General of the Army, aged seventy-five, in 1931. He

expressed interest in being named Minister of Education, a role in

which he hoped to combat what he saw as the decay in French moral

values. In 1934 he was appointed to the French cabinet as Minister of War. The following year, he was promoted to Secretary of State.

During this period, he repeatedly called for a lengthening of the term

of compulsory military service for draftees entering the military service, from two to three years. As

France's most senior soldier after Foch's death, Marshal Petain's must

bear some responsibility for the poor state of French weaponry

preparation before World War II. This was particularly ironic in view

of his championing of (what were then) modern tactics before World War

I. Although he supported the massive use of tanks he saw them mostly as

infantry support, leading to the fragmentation of the French tank force

into many types of unequal value spread out between mechanized cavalry

(such as the SOMUA S-35) and infantry support (mostly the Renault R35 tanks and the Char B1 bis).

Modern infantry rifles and machine guns were not manufactured on

Pétain's watch, with the sole exception of a light

machine-rifle, the Mle 1924. A modern infantry rifle prototype only came out in 1936 but very few of these MAS-36 rifles

had been issued to the troops by 1940. An excellent French

semiautomatic rifle prototype, the MAS 1938-40, never reached the

production stage until after World War II as the MAS 49.

Thus French infantry had to face the enemy in 1940 with the old

weaponry of 1918. Petain was made Minister of War in 1938, thus

overseeing French military aviation and the Navy as well. Yet French

aviation entered the War in 1939 without even the prototype of a bomber

airplane capable of reaching Berlin and coming back. French industrial

efforts in fighter aircraft were dispersed among several firms (Dewoitine, Morane-Saulnier and Marcel Bloch),

each with its own model. On the naval front France had purposely

overlooked building modern aircraft carriers and focused instead on

four new conventional battleships which later proved to be useless to

the war effort. Pétain served as French ambassador to Spain following the Nationalist victory in the Spanish Civil War, arriving in March 1939. Until the summer of 1940, Pétain was held in high regard by statesmen both at home and abroad. French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud brought Pétain, General Maxime Weygand and the newly-promoted Brigadier-General de Gaulle,

whose 4th Armoured Division had launched one of the few French

counterattacks in May 1940, into his War Cabinet, hoping that the trio,

and especially Pétain, would instill a renewed spirit of

resistance and patriotism in the French army. The social and political

divisions in France were too great, however, and Reynaud had misjudged

Pétain, a man who despised the corruption, inefficiency and

political fragmentation of the French Third Republic. Maxime Weygand was unable to stem the German advance during the second stage of the Battle of France.

When defeat for metropolitan France became certain, the Cabinet debated

their continuing the war in North Africa, to fight on from the colonial

territory alongside the British. Pétain's refusal to leave the

country at this juncture created an impasse that divided the Cabinet

and which was only broken by Reynaud's resignation and President Albert Lebrun's

invitation to Pétain to form a government. Lebrun soon became

sidelined, leading to the appointment of the old Marshal as head of

state with extraordinary powers. The constitutionality of these actions

was later challenged by de Gaulle's government, but at the time

Pétain was widely accepted as France's saviour. On 22 June he signed an armistice with Germany that gave Nazi Germany control

over the north and west of the country, including Paris and all of the

Atlantic coastline, but left the rest, around two-fifths of France's

prewar territory, unoccupied, with its administrative centre in the

resort town of Vichy. (Paris remained the de jure capital.) The Chamber of Deputies and Senate, meeting together as a "Congrès", had an emergency meeting on 10 July to ratify the armistice. At the same time, it voted 569-80 (with

18 abstentions) to grant Pétain the authority to draw up a new

constitution, effectively voting the Third Republic out of existence. On the next day, Pétain formally assumed near-absolute powers as "Head of State". Pétain

was reactionary by temperament and education, and quickly began blaming

the Third Republic and its liberal democracy for the French defeat. In

its place, he set up a more authoritarian regime. The republican motto

of "Liberté, égalité, fraternité" was swept aside and replaced with "Travail, famille, patrie" (Work, family, fatherland). Fascistic

factions and revolutionary conservative factions within the

Pétain government used the opportunity to launch an ambitious

program known as the "National Revolution" in which much of the former

Third Republic's secular and liberal traditions were rejected in favor

of the promotion of an authoritarian and paternalist Catholic society.

Pétain, amongst others, took exception to the use of the

inflammatory term "revolution" to describe an essentially conservative

movement but was otherwise a willing participant in the transformation

of French society from "Republic" to "State". He himself described

Vichy France as "a social hierarchy...rejecting the false idea of the

natural equality of men". Pétain

immediately used his new powers to order harsh measures, including the

dismissal of republican civil servants, the installation of exceptional

jurisdictions, the proclamation of anti-Semitic laws, and the

imprisonment of his opponents and foreign refugees. He organized a "Légion Française des Combattants",

in which he included "Friends of the Legion" and "Cadets of the

Legion", groups of those who had never fought but who were politically

attached to his regime. Pétain championed a rural, Catholic

France that spurned internationalism. As a retired Generalissimo, he

ran the country on military lines, which might have been better

received had he not already surrendered to Adolf Hitler's

Germany. While to historians and modern day observers Pétain was

clearly Hitler's puppet, at the time many Frenchmen believed that de

Gaulle and his Free French were similarly in the hands of foreign

powers. However, after 1942 it became increasingly clear that the

Maréchal was Hitler's puppet. Neither Pétain nor his successive Deputies, Pierre Laval, Pierre-Etienne Flandin or Admiral François Darlan, gave significant resistance to requests by the Germans to indirectly aid the Axis Powers. Yet, when Hitler met Pétain at Montoire in

October 1940 to discuss Vichy's role in the new European Order, the

Marshal "listened to Hitler in silence. Not once did he offer a

sympathetic word for Germany". However, Vichy France remained neutral

as a state, albeit opposed to the Free French. After the British attack on Mers el Kébir and Dakar,

Pétain took the initiative to collaborate with the occupiers.

Pétain accepted the creation of a collaborationist armed militia

("Milice") under the command of Joseph Darnand, who, along with German forces, led a campaign of repression against the French resistance ("Maquis"). The "honours" Darnand acquired included SS-Major. Pétain admitted Darnand into his government as Secretary of the Maintenance of Public Order (Secrétaire d'Etat au Maintien de l'Ordre). In August 1944, Pétain made an attempt to distance himself from the crimes of the Milice by writing Darnand a letter of reprimand for the organization's "excesses." The

latter wrote a sarcastic reply, telling Pétain that he should

have "thought of this before". Such were the crimes of Frenchmen

against Frenchmen - and in 1944-5 those Frenchmen and women who had

backed the losing side were dealt terrible treatment when Liberation finally came. Pétain

provided the Axis forces with large supplies of manufactured goods and

foodstuffs, and also ordered Vichy troops in France's colonial empire to fight against Allied forces everywhere (in Dakar, Syria, Madagascar, Oran and Morocco), in line with his commitments in the 1940 armistice. He also received German forces without any resistance (in Syria, Tunisia and Southern France), the latter due to Laval's urging. On 11 November 1942, Germany invaded the unoccupied zone in response to the Allied Operation Torch landings in North Africa and Vichy Admiral François Darlan's

agreeing to support the Allies. Although Vichy France nominally

remained in existence, Pétain became nothing more than a figurehead,

as the Nazis abandoned the pretense of an "independent" Vichy

government. After 7 September 1944, Petain and other members of the

Vichy cabinet were relocated to Sigmaringen Germany, where they established a government-in-exile until April 1945. Pétain, who had been forcibly brought there by the Germans, refused to participate in the governmental commission, which was headed by Fernand de Brinon. On 15 August 1945, Pétain was tried for collaboration (or treason), convicted and sentenced to cashiering and death by firing squad.

He

was therefore stripped of all his military ranks and honours except

that of Maréchal (because Maréchal is a distinction

conferred by a special personal law passed by the French Parliament,

and under the principle of separation of powers a court does not have the power to revert a law passed by Parliament). As to the death sentence, Charles de Gaulle, who was President of the Provisional Government of the French Republic at

the end of the war, commuted it to life imprisonment on the grounds of

Pétain's age and his World War I contributions. In prison on Île d'Yeu,

an island off the Atlantic coast, he soon became entirely senile, and

required constant nursing care. He died in prison at Fort de Pierre de

Levée in 1951, at the age of 95. His body is buried at a marine cemetery near the prison. Calls are sometimes made for his remains to be re-interred in the grave which had been prepared for him at Verdun.