<Back to Index>

- Naturalist Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, Chevalier de la Marck, 1744

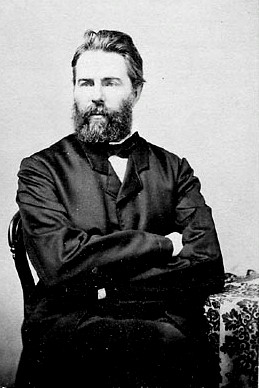

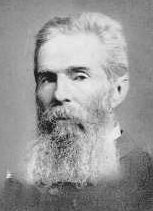

- Novelist Herman Melville, 1819

- Prime Minister of Serbia Zoran Đinđić, 1952

Herman Melville (August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American novelist, short story writer, essayist and poet, whose work is often classified as part of the genre of dark romanticism. He is best known for his novel Moby-Dick and novella Billy Budd, the latter of which was published posthumously.

His

first three books gained much attention, the first becoming a

bestseller, but after a fast-blooming literary success in the late

1840s, his popularity declined precipitously in the mid-1850s and never

recovered during his lifetime. When he died in 1891, he was almost

completely forgotten. It was not until the "Melville Revival" in the

early 20th century that his work won recognition, most notably Moby-Dick which

was hailed as one of the chief literary masterpieces of both American

and world literature. He was the first writer to have his works

collected and published by the Library of America. Herman Melville was born in New York City on August 1, 1819, as

the third child of Allan and Maria Gansevoort Melvill. After her

husband Allan died, Maria added an "e" to the family surname. Part of a

well-established and colorful Boston family,

Melville's father spent a good deal of time abroad doing business deals

as a commission merchant and an importer of French dry goods. The

author's paternal grandfather, Major Thomas Melvill, an honored

survivor of the Boston Tea Party who refused to change the style of his clothing or manners to fit the times, was depicted in Oliver Wendell Holmes's

poem "The Last Leaf". Herman visited him in Boston, and his father

turned to him in his frequent times of financial need. The maternal

side of Melville's family was Hudson Valley Dutch. His maternal

grandfather was General Peter Gansevoort, a hero of the battle of Saratoga; in his gold-laced uniform, the general sat for a portrait painted by Gilbert Stuart. The portrait is mentioned and described in Melville's 1852 novel, Pierre, for Melville wrote out of his familial as well as his nautical background. Like the titular character in Pierre, Melville found satisfaction in his "double revolutionary descent." Allan

Melvill sent his sons to the New York Male School (Columbia Preparatory

School). Overextended financially and emotionally unstable, Allan tried

to recover from his setbacks by moving his family to Albany in 1830 and going into the fur business. The new venture, however, was unsuccessful: the War of 1812 had ruined businesses that tried to sell overseas and he was forced to declare bankruptcy. He died soon afterward, leaving his family penniless, when Herman was 12. Although

Maria had well-off kin, they were concerned with protecting their own

inheritances and taking advantage of investment opportunities rather

than settling their mother's estate so Maria's family would be more

secure. Herman's younger brother, Thomas Melville, eventually became a governor of Sailors Snug Harbor. Melville attended the Albany Academy from October 1830 to October 1831, and again from October 1836 to March 1837, where he studied the classics. Herman

Melville's roving disposition and a desire to support himself

independently of family assistance led him to seek work as a surveyor

on the Erie Canal. This effort failed, and his brother helped him get a

job as a cabin boy on a New York ship bound for Liverpool. He made the voyage, and returned on the same ship. Redburn: His First Voyage (1849) is partly based on his experiences of this journey. The

three years after Albany Academy (1837 to 1840) were mostly occupied

with school-teaching, except for the voyage to Liverpool in 1839. Near

the end of 1840 he once again decided to sign ship's articles. On January 3, 1841, he sailed from New Bedford, Massachusetts on the whaler Acushnet, which was bound for the Pacific Ocean. He was later to comment that his life began that day. The vessel sailed around Cape Horn and

traveled to the South Pacific. Melville left little direct information

about the events of this 18-month cruise, although his whaling romance, Moby-Dick; or, The Whale, probably gives many pictures of life onboard the Acushnet. Melville deserted the Acushnet in the Marquesas Islands in July 1842. For three weeks he lived among the Typee natives, who were called cannibals by the two other tribal groups on the island -- though they treated Melville very well. His book Typee was

Melville's first novel. It describes a brief love affair with a

beautiful native girl, Fayaway, who generally "wore the garb of Eden"

and came to epitomize the guileless noble savage in the popular imagination. We have no independent evidence, however, of Melville's actual activities among the islanders. Melville did not seem to be concerned about repercussions from his desertion from the Acushnet. He boarded another whaler bound for Hawaii and left that ship in Honolulu.

While in Honolulu, he became a controversial figure for his vehement

opposition to the activities of Christian missionaries seeking to

convert the native population. After working as a clerk for four months

he joined the crew of the frigate USS United States, which reached Boston in October 1844. These experiences were described in Typee, Omoo, and White-Jacket, which were published as novels mainly because few believed their veracity. Melville completed Typee in the summer of 1845 though he had difficulty getting it published. It

was eventually published in 1846 in London, where it became an

overnight bestseller. The Boston publisher subsequently accepted Omoo sight unseen. Typee and Omoo gave

Melville overnight notoriety as a writer and adventurer and he often

entertained by telling stories to his admirers. As writer and editor Nathaniel Parker Willis wrote, "With his cigar and his Spanish eyes, he talks Typee and Omoo, just as you find the flow of his delightful mind on paper". The novels, however, did not generate enough royalties for him to live on. Omoo was not as colorful as Typee, and readers began to realize Melville was not just producing adventure stories. Redburn and White-Jacket had no problem finding publishers. Mardi was a disappointment for readers who wanted another rollicking and exotic sea yarn. Melville married Elizabeth Shaw (daughter of chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Lemuel Shaw) on August 4, 1847; the couple honeymooned in Canada. They had four children, two sons and two daughters. In 1850 they purchased Arrowhead, a farm house in Pittsfield, Massachusetts,

now a museum. Here Melville lived for thirteen years, occupied with his

writing and managing his farm. While living at Arrowhead, he befriended

the author Nathaniel Hawthorne, who lived in nearby Lenox.

Melville, an intellectual loner for most of his life, was tremendously

inspired and encouraged by his new relationship with Hawthorne during the period that he was writing Moby-Dick (dedicating it to Hawthorne), though their friendship was on the wane only a short time later, when he wrote Pierre there. However, these works did not achieve the popular and critical success of his earlier books. Indeed, The New York Day Book on 8 September 1852 published a venomous attack on Melville and his writings headlined HERMAN MELVILLE CRAZY. The

item, offered as a news story, reported, "A critical friend, who read

Melville's last book, 'Ambiguities," between two steamboat accidents,

told us that it appeared to be composed of the ravings and reveries of

a madman. We were somewhat startled at the remark, but still more at

learning, a few days after, that Melville was really supposed to be

deranged, and that his friends were taking measures to place him under

treatment. We hope one of the earliest precautions will be to keep him

stringently secluded from pen and ink." Following this and other scathing reviews of Pierre by critics, publishers became wary of Melville's work. His publisher, Harper & Brothers, rejected his next manuscript, Isle of the Cross which has been lost. On April Fool's Day 1857, Melville published what would be the last full-length novel he published, The Confidence-Man.

This novel, subtitled "His Masquerade," has won general acclaim in

modern times as a complex and mysterious exploration of issues of fraud

and honesty, identity and masquerade, but when it was published, it

received reviews ranging from the bewildered to the denunciatory. To

repair his faltering finances, Melville listened to the advice of

friends and decided to enter what was for others the lucrative field of

lecturing. From 1857 to 1860, he spoke at lyceums, chiefly on the South

Seas. Turning to poetry, he gathered a collection of verse that failed

to interest a publisher. In 1863, he and his wife resettled, with their

four children, in New York City. After the end of the American Civil War, he published Battle Pieces and Aspects of the War,

(1866) a collection of over seventy poems that generally was ignored by

the critics, though a few gave him patronizingly favorable reviews. In

1866, Melville's wife and her relatives used their influence to obtain

a position for him as customs inspector for the City of New York (a

humble but adequately paying appointment), and he held the post for 19

years. In a notoriously corrupt institution, Melville soon won the

reputation of being the only honest employee of the customs house. (The

customs house was coincidentally on Gansevoort St., named after his

mother's prosperous family.) But from 1866 his professional writing

career can be said to have come to an end. Melville spent years writing a 16,000-line epic poem, Clarel,

inspired by his earler trip to the Holy Land. His uncle, Peter

Gansevoort, by a bequest, paid for the publication of the massive epic

in 1876. But the publication failed miserably, and the unsold copies

were burned when Melville was unable to afford to buy them at cost. As

his professional fortunes waned, Melville's marriage was unhappy,

plagued by rumors of his alcoholism and insanity and allegations that

he inflicted physical abuse on his wife. Her relatives repeatedly urged

her to leave him, and offered to have him committed as insane, but she

refused. In 1867 his oldest son, Malcolm, shot himself, perhaps

accidentally. While Melville worked, his wife managed to wean him off

alcohol, and he no longer showed signs of agitation or insanity. But

recurring depression was added-to by the death of his second son,

Stanwix, in San Francisco early in 1886. Melville retired in 1886,

after several of his wife's relatives died and left the couple legacies

that Mrs. Melville administered with skill and good fortune. As English readers, pursuing the vogue for sea stories represented by such writers as G.A. Henty,

rediscovered Melville's novels, he experienced a modest revival of

popularity in England, though not in the United States. Once more he

took up his pen, writing a series of poems with prose head notes

inspired by his early experiences at sea. He published them in two

collections, each issued in a tiny edition of 25 copies for his

relatives and friends: John Marr (1888) and Timoleon (1891). One

of these poems further intrigued him, and he began to rework the

headnote to turn it into at first a short story and then a novella. He

worked on it on and off for several years, but when he died in

September 1891, he left the piece unfinished, and not until the

literary scholar Raymond Weaver published it in 1924 did the book –

which we now know as Billy Budd, Sailor – come to light. Melville

died at his home in New York City early on the morning of September 28,

1891, age 72. The doctor listed "cardiac dilation" on the death

certificate. He was interred in the Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York. From

about age thirty-three, Melville ceased to be popular with a broad

audience because of his increasingly philosophical, political, and

experimental tendencies. His novella Billy Budd, Sailor, unpublished at the time of his death, was published in 1924. Later it was turned into an opera by Benjamin Britten, a play, and a film by Peter Ustinov. In Herman Melville's Religious Journey, Walter Donald Kring detailed his discovery of letters indicating that Melville had been a member of the Unitarian Church

of All Souls in New York City. Until this revelation, little had been

known of his religious affiliation. Hershel Parker in the second volume

of his biography makes it clear that Melville became a nominal member

only to placate his wife. Melville despised Unitarianism and its

associated "ism", Utilitarianism. (The great English Unitarians were

Utilitarians.)