<Back to Index>

- Mathematician William Rowan Hamilton, 1805

- Poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, 1792

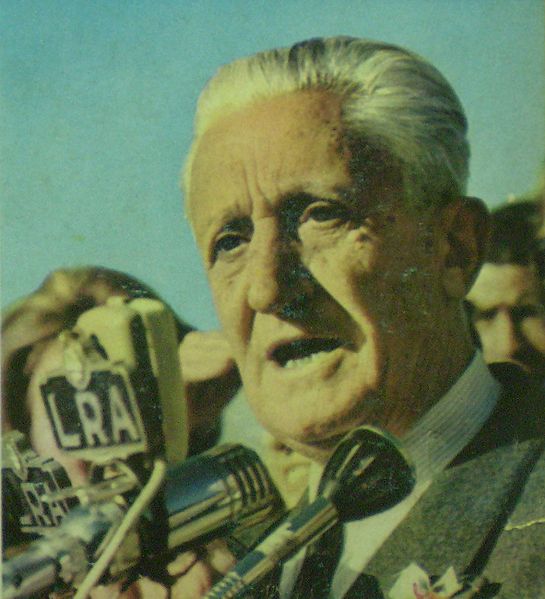

- President of Argentina Arturo Umberto Illia Francesconi, 1900

Arturo Illia (August 4, 1900 – January 18, 1983) was President of Argentina from October 12, 1963, to June 28, 1966, and a member of the centrist UCR.

Arturo Umberto Illia Francesconi was born August 4, 1900, in Pergamino, Buenos Aires Province, to Emma Francesconi and Martín Illia, Italian Argentine immigrants from the Lombardy Region.

He enrolled in the School of Medicine at the University of Buenos Aires in 1918. That year, he joined the movement for University reform in Argentina (Reforma Universitaria), which first emerged in the city of Córdoba, and set the basis for a free, open and public university system less influenced by the Catholic Church. This development changing the concept and administration of higher education in Argentina, and in a good portion of Latin America. As a part of his medical studies, Illia begun working in the San Juan de Dios Hospital in the city of La Plata, obtaining his degree in 1927.

In 1928 he had an interview with President Hipólito Yrigoyen, the longtime leader of the centrist UCR, and the first freely-elected President of Argentina. Illia offered him his services as a physician, and Yrigoyen, in turn, offered him a post as railroad medic in different parts of the country, upon which Illia decided to move to scenic Cruz del Eje, in Cordoba Province. He worked there as a medic from 1929 until 1963, except for three years (1940-1943) in which he was Vice-Governor of the province.

On

February 15, 1939, he married Silvia Elvira Martorell, and had three

children: Emma Silvia, Martín Arturo and Leandro

Hipólito. Martín Illia was elected to Congress in 1995, and served until his death in 1999. Arturo Illia became a member of the Radical Civic Union when

he reached adulthood, in 1918, under the strong influence of the

radical militancy of his father and of his brother, Italo. That same

year, he began his university studies, with the events of the

aforementioned Universitarian Reform taking place in the country. From

1929 onwards, after moving to Cruz del Eje, he began intense political

activity, which he alternated with his professional life. In 1935 he

was elected Provincial Senator for the Department of Cruz del Eje, in

the elections that took place on November 17. In the Provincial Senate,

he actively participated in the approval of the Law of Agrarian Reform, which was passed in the Córdoba Legislature but rejected in the National Congress. He

was also head of the Budget and Treasury Commission, and pressed for

the construction of dams, namely Nuevo San Roque, La Viña, Cruz

del Eje and Los Alazanes. In the elections that took place on March 10, 1940, he was elected Vice-Governor of Córdoba Province, with Santiago del Castillo, who became Governor. He occupied this post until the provincial

government was replaced by the newly-installed dictatorship of General Pedro Ramírez, in 1943. From 1948 to 1952, Illia served in the Argentine Chamber of Deputies. Working in a Congress dominated by the Peronist Party, he took an active part in the Public Works, Hygiene and Medical Assistance Commissions. After the fall of the populist government of Juan Perón in 1955, a long period of political instability took over Argentina.

During this period, the army would have a large influence over the

politics of the country, and, even though elections would still take

place, these would be marked by a considerable lack of legitimacy, since Peronism (which

was supported by a great portion of the Argentine citizenry) would be

banned during this period. From 1955 to 1963 the country had five

presidents, of which only one was democratically elected: Arturo Frondizi,

who governed the country from May 1, 1958, until his March 29, 1962,

overthrow by a military coup. Frondizi's removal was precipitated by

his lifting the ban on Peronism ahead of the March 1962 mid-term elections.

Among those also affected was Illia, who, though a UCR candidate, was

thus barred from office following his election as Governor of

Córdoba. After the fall of Frondizi, the President of the Senate, José María Guido,

became interim President of the country, starting a process of

'normalization' which would eventually lead to new elections, on July

7, 1963. The 1963 elections were made possible by support from the moderate, "Blue" faction of the Argentine military, led by the Head of the Joint Chiefs, General Juan Carlos Onganía and by the Internal Affairs Minister, General Osiris Villegas.

Together, they exercised control over Guido's puppet presidency –

though they shared his commitment to elections. The UCR, out of power

since Yrigoyen's 1930 overthrow, had been divided since their

contentious 1956 convention into the mainstream "People's UCR" (UCRP)

and the center-left UCRI. The leader of the UCRP, Ricardo Balbín,

withdrew his name from the March 10 nominating convention and instead

supported a less conservative, less anti-Peronist choice, and the party

nominated Dr. Illia for President and Entre Ríos Province lawyer Carlos Perette as his running-mate. A

military ban on the Popular Front organized by Perón and

Frondizi led to their joint call for blank voting as a means of

protest. The moderately anti-Peronist UCRP was also hampered by former

President Pedro Aramburu's

candidacy, which made opposition to Perón central to its

platform. Ultimately, however, Illia would win, and despite carrying

only a fourth of the vote, he also "defeated" the blank vote option (a

proxy for the Perón vote) by 4 points. The results were: In

the electoral college on July 31, 1963, the Illia-Perette ticket

obtained 169 votes out of 476 on the first round of voting (70 short of

an absolute majority), but the support of three centrist parties on the

second round gave them 270 votes, thus formalizing their election. Arturo

Illia became President on October 12, 1963, and promptly steered a

moderate political course, while remaining mindful of the spectre of a coup d'état. A UCRP majority in the Senate contrasted

with their 73 seats in the 192-seat Lower House, a disadvantage

complicated by Illia's refusal to include UCRI men in the cabinet

(which, save for Internal Affairs Minister Juan Palmero, would all be

figures close to Balbín). Illia also refused military requests

to have a general put in charge of the Federal District Police, though he confirmed Onganía as Head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and named numerous "Blue" generals to key posts. Countering

military objections, he made political rights an early policy

centerpiece, however. His first act consisted in eliminating all

restrictions over Peronism and

its allied political parties, causing anger and surprise among the

military (particularly the right-wing "Red" faction). Political

demonstrations from the peronist party were forbidden after the 1955

coup, by the Presidential Decree 4161/56, however, five days after

Illia's inaugural, a Peronist commemorative act for the 17th of October

(in honor of the date in 1945 when labor demonstrations propelled

Perón to power) took place in Buenos Aires' Plaza Miserere without any official restrictions. Illia similarly lifted electoral restrictions, allowing the participation of Peronists in the 1965 legislative elections. The prohibition over the Communist Party of Argentina and the pro-industry MID (which

many in the military, then controlled by cattle barons, termed

"economic criminals") was also lifted. Among Illia's early landmark

legislation was an April 1964 bill issuing felony penalties for

discrimination and racial violence, which he presented in an address to

a joint session of Congress. Domestically,

Illia pursued a pragmatic course, restoring Frondizi's vigorous public

works and lending policies, but with more emphasis on the social aspect

and with a marked, nationalist shift away from Frondizi's support for foreign investment. This shift was most dramatic in Illia's energy policy. On

November 15, 1963, Illia issued the decrees 744/63 and 745/63, which

rendered said oil contracts null and void, for being considered "illegitimate and harmful to the rights and interests of the Nation.". Frondizi

had begun, during his 1958-62 presidency, a policy of oil exploration

based on concessions of oil wells to foreign private corporations, leaving the state oil company Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales (YPF)

the sole responsibility of exploration and buying oil from private

extractors. Arguing that such contracts were negative for the Argentine

state and its people (YPF had to assume all the risks of investing in

exploration of new wells, the price of oil had risen steadily since the

contracts were negotiated, etc.), Illia denounced the Frondizi policy

as negative for national Argentine interests, and promised to render

the contracts of concession void, renegotiating them. On June 15, 1964, the Law 16.459 was passed, establishing a minimum wage for the country. "Avoiding the exploitation of workers in those sectors in which an excess of workforce may exist", "Securing an adequate minimum wage" and "Improving the income of the poorest workers" were listed among the objectives of the project. With

the same aims, the Law of Supplies was passed, destined to control

prices of basic foodstuffs and setting minimum standards for pensions. During

Illia's government, education acquired an important presence in the

national budget. In 1963, it represented 12% of the budget, rising to

17% in 1964 and to 23% in 1965. On

November 5, 1964, the National Literacy Plan was started, with the

purpose of diminishing and eliminating illiteracy (At the time, nearly

10% of the adult population was still illiterate). By June, 1965, the

program comprised 12,500 educational centers and was assisting more

than 350,000 adults of all ages. Law

16.462, also known as 'Oñativia Law' (in honor of Minister of

Health Arturo Oñativia), was passed on August 28, 1964. It

established a policy of price and quality controls for pharmaceuticals,

freezing prices for patented medicines at the end of 1963, establishing

limits to advertising expenditures and to money sent outside the

country for royalties and related payments. The reglamentation of this

law by the Decree 3042/65, also forced pharmaceutical corporations to

present, to a judge, an analysis of the costs of their drugs and to

formalize all their existing contracts. Both

supporters, detractors and impartial observers of Illia agree that this

policy helped array opposition by business interests that was decisive

in his eventual overthrow by a military coup. In

the economic sphere, Arturo Illia's presidency was characterised by

regulation of the public sector, a decrease of the public debt, and a

considerable push for industrialization. The Syndicate of State

Businesses was created, to achieve a more efficient control of the

public sector. Among his brief presidency's most notable public works

initiatives were the Villa Lugano housing development (in the poorest section of Buenos Aires) and El Chocón Dam, then the largest such project in Argentina. National

GDP had contracted by 2.4% in 1963; it expanded by 10.3% in 1964 and

9.1% in 1965. Industrial GDP had shrunk by 4.1% in 1963; it leapt by

18.9% in 1964 and 13.8% in 1965. The external debt was reduced from 3.4

billion dollars to 2.7 billion.

The median real wage grew by 9.6% during calendar 1964, alone, and had

expanded by almost 25% by the time of the coup. Unemployment declined

from 8.8% in 1963, to 5.2% on 1966. Ironically,

the Argentine middle class (who were generally as anxious as anyone to

see President Illia leave office) benefited even more: auto sales leapt

from 108,000 in 1963 to 192,000 in 1965 (a record at the time). Organized

labour initially supported Illia for his expansionist economic policy.

This support turned to antagonism during 1964, however, as secret plans

for Perón's return from exile took shape. Accordingly, CGT labor union head José Alonso called a general strike in

May, and became a vocal opponent of the president's – this

antagonism intensified after Perón's failed attempt to return in

December, and during 1965, CGT leaders began publicly hinting at

support for a coup. Legislative

elections took place on March 17, and despite the unions' hostility

towards Illia, Peronists were free of the restrictions existing up to

1963. Thanks to this, the Peronists presented their own party lists,

rallying behind the Popular Union. The Popular Union won the popular

vote (3,278,434 votes against Illia's UCRP, which obtained 2,734,970

votes), and elected 52 Congressmen (the first time Peronists had been

allowed to do so in a decade). The

triumph of the Peronists shook the Argentine Armed Forces, both among

internal military factions linked to the Peronist movement, and in

particular among the large section of the army which remained strongly

anti-Peronist. In addition, a campaign against the government was also

being carried out by important parts of the media, notably Primera Plana and Confirmado, the nation's leading news magazines. Seizing on minimally relevant events such as the President's refusal to support Operation Power Pack (Lyndon Johnson's ill-justified, April 1965 invasion of the Dominican Republic),

Illia was nicknamed "the turtle" in both editorials and caricatures,

and his rule was vaguely referred to as "slow," "dim-witted" and

"lacking energy and decision," encouraging the military to take power

and weakening the government even more; Confirmado went further, publicly exhorting the public to support a coup and publishing a (non-scientific) opinion poll touting public support for the illegal measure. Under the planning of the Commander of the First Division of the Army, General Julio Alsogaray,

and with the support of the military, the US government, economic

groups, a considerable part of the media, and numerous politicians

(notably UCRI leader Oscar Alende, former President Frondizi, and Alsogaray's brother, right-wing economist Alvaro Alsogaray),

the military coup took place on June 28, 1966. General Alsogaray

presented himself in Illia's office that day, at 5:00 a.m, and

'invited' him to resign his post. Illia

refused to do so at first, citing his role as Commander-in-Chief, but

at 7:20, after seeing his office invaded by military officers and

policemen with grenade launchers, he was forced to step down. The next

day, General Juan Carlos Onganía became the new Argentine President. Illia

lost his wife, Silvia Martorell, to cancer in November of that year. He

then relocated to the upscale Buenos Aires suburb of Martínez, though he would still make frequent trips to Córdoba. He continued participating in politics actively in support of the UCR until his death in Córdoba on January 18, 1983. Following a state memorial in Congress, Arturo Umberto Illia was buried in La Recoleta Cemetery, in Buenos Aires.