<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Gilles Personne de Roberval, 1602

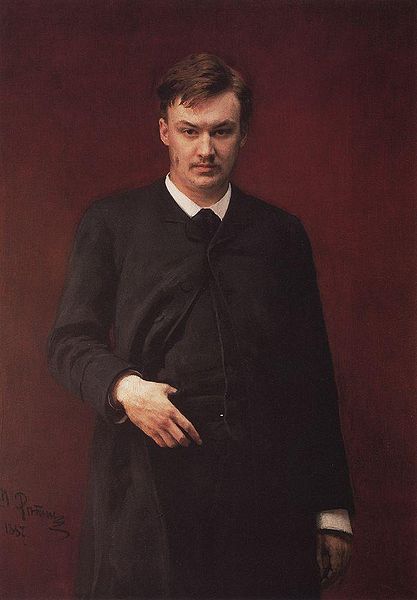

- Composer Alexander Konstantinovich Glazunov, 1865

- 1st Prime Minister of Italy Camillo Paolo Filippo Giulio Benso, Conte di Cavour, 1810

Alexander Konstantinovich Glazunov (Russian: Александр Константинович Глазунов; 10 August [O.S. 29 July] 1865 – 21 March 1936) was a Russian composer of the late Russian Romantic period, music teacher and conductor. He served as director of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory between 1905 and 1928 and was also instrumental in the reorganization of the institute into the Petrograd Conservatory, then the Leningrad Conservatory, following the Bolshevik Revolution. He continued heading the Conservatory until 1930, though he had left the Soviet Union in 1928 and did not return. The best known student under his tenure during the early Soviet years was Dmitri Shostakovich.

Glazunov was significant in that he successfully reconciled nationalism and cosmopolitanism in Russian music. While he was the direct successor to Balakirev's nationalism, he tended more towards Borodin's epic grandeur while absorbing a number of other influences. These included Rimsky-Korsakov's orchestral virtuosity, Tchaikovsky's lyricism and Taneyev's contrapuntal skill. His weaknesses were a streak of academicism which sometimes overpowered his inspiration and an eclecticism which could sap the ultimate stamp of originality from his music. Younger composers such as Prokofiev and

Shostakovich eventually considered his music old-fashioned while also

admitting he remained a composer with an imposing reputation and a

stabilizing influence in a time of transition and turmoil. Glazunov was born in Saint Petersburg and was the son of a wealthy publisher (his father had published Alexander Pushkin's Eugene Onegin). He began studying piano at the age of nine and began composing at 11. Mily Balakirev, former leader of the nationalist group "The Five", recognized Glazunov's talent and brought his work to the attention of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov.

"Casually Balakirev once brought me the composition of a fourteen- or

fifteen-year-old high-school student, Sasha Glazunov", Rimsky-Korsakov

remembered. "It was an orchestral score written in childish fashion.

The boy's talent was indubitably clear." Balakirev

introduced him to Rimsky-Korsakov shortly afterwards, in December 1879.

Rimsky-Korsakov premiered this work in 1882, when Glazunov was 16. Borodin and Stasov, among others, lavishly praised both the work and its composer. Rimsky-Korsakov taught Glazunov as a private student. "His musical development progressed not by the day, but literally by the hour", Rimsky-Korsakov wrote. The

nature of their relationship also changed. By the spring of 1881,

Rimsky-Korsakov considered Glazunov more of a junior colleague than a

student. While part of this development may have been from Rimsky-Korsakov's need to find a spiritual replacement for Modest Mussorgsky, who had died that March, it may have also been from observing his progress on the first of Glazunov's eight symphonies. More important than this praise was that among the work's admirers was a wealthy timber merchant and amateur musician, Mitrofan Belayev. Belayev was introduced to Glazunov's music by Anatoly Lyadov and would take a keen interest in the teenager's musical future, then extend that interest to an entire group of nationalist composers. Belayev took Glazunov on a trip to Western Europe in 1884. Glazunov met Liszt in Weimar, where Glazunov's First Symphony was performed. Also

in 1884, Belayev rented out a hall and hired an orchestra to play

Glazunov's First Symphony plus an orchestral suite Glazunov had just

composed. Buoyed

by the success of the rehearsal, Belayev decided the following season

to give a public concert of works by Glazunov and other composers. This project grew into the Russian Symphony Concerts, which were inaugurated during the 1886–1887 season. In 1885 Belayev started his own publishing house in Leipzig, Germany, initially publishing music by Glazunov, Anatoly Lyadov, Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Borodin at

his own expense. Young composers started appealing for his help. To

help select from their offerings, Belayev asked Glazunov to serve with

Rimsky-Korsakov and Lyadov on an advisory council. The group of composers that formed eventually became known at the Belayev Circle.

Glazunov

soon enjoyed international acclaim. Nevertheless, he experienced a

creative crisis in 1890–1891. He came out of this period with a new

maturity. During the 1890s he wrote three symphonies, two string

quartets and the ballet Raymonda.

By the time he was elected director of the Saint Petersburg

Conservatory in 1905, he was at the height of his creative powers. His

best works from this period are considered his Eighth Symphony and Violin Concerto.

This was also the time of his greatest international acclaim. He

conducted the last of the Russian Historical Concerts in Paris on 17

May 1907 and received honorary Doctor of Music degrees

from the universities of Oxford and Cambridge. There were also cycles

of all-Glazunov concerts in Saint Petersburg and Moscow to celebrate

his 25th anniversary as a composer. Glazunov

made his conducting debut in 1888. The following year, he conducted his

Second Symphony in Paris at the World Exhibition. He was appointed conductor for the Russian Symphony Concerts in 1896. In March of that year he conducted the posthumous premiere of Tchaikovsky's student overture The Storm. In 1897, he led the disastrous premiere of Rachmaninoff's Symphony No 1.

The composer's wife later claimed that Glazunov seemed to be drunk at

the time. While this assertion cannot be confirmed, it is not

implausible for a man who, according to Shostakovich, kept a bottle of

alcohol hidden behind his desk and sipped it through a tube during

lessons. Drunk

or not, Glazunov had insufficient rehearsal time with the symphony and,

while he loved the art of conducting, he never fully mastered it. From time to time he conducted his own compositions, especially the ballet Raymonda,

even though he may have known he had no talent for it. He would

sometimes joke, "You can criticize my compositions, but you can't deny

that I am a good conductor and a remarkable conservatory Director." Despite the hardships he suffered during World War I and the ensuing civil war, Glazunov remained active as a conductor. He conducted concerts in factories, clubs and Red Army posts. He played a prominent part in the Russian observation in 1927 of the centenary of Beethoven's

death, as both speaker and conductor. After he left Russia, he

conducted an evening of his works in Paris in 1928. This was followed

by engagements in Portugal, Spain, France, England, Czechoslovakia, Poland, the Netherlands, and the United States. In 1899, Glazunov became a professor at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. In the wake of the 1905 Russian Revolution and firing, then re-hiring of Rimsky-Korsakov that year, Glazunov became its director. He remained so until the revolutionary events of 1917,

which culminated on 7 November. His Piano Concerto No. 2 in B minor,

Op. 100, which he conducted, was premiered at the first concert

held in Petrograd after that date. After

the end of World War I, he was instrumental in the reorganization of

the Conservatory — this may, in fact, have been the main reason he waited

so long to go into exile. During

his tenure he worked tirelessly to improve the curriculum, raise the

standards for students and staff, as well as defend the institute's

dignity and autonomy. Among his achievements were an opera studio and a

students' philharmonic orchestra. Glazunov showed paternal concern for the welfare of needy students, such as Dmitri Shostakovich and Nathan Milstein. He also personally examined hundreds of students at the end of each academic year, writing brief comments on each. Unfortunately, according to Shostakovich's comments in Testimony,

Glazunov's alcoholism may have progressed to the point that he could

not give a lesson while sober. Glazunov taught only chamber music by

the time Shostakovich was a student. Glazunov sat at his desk, not

interrupting the music being played during class. He spoke quietly and

briefly, his comments becoming less distinct and briefer toward the end

of the lesson. While

Glazunov's sobriety could be questioned, his prestige was not. Because

of his reputation, the Conservatory received special status among

institutions of higher learning in the aftermath of the October Revolution. Glazunov established a sound working relationship with the Bolshevik regime, especially with Anatoly Lunacharsky,

the minister of education. Nevertheless, Glazunov's conservatism was

attacked within the Conservatory. Increasingly, professors demanded

more progressive methods, and students wanted greater rights. Glazunov

saw these demands as both destructive and unjust. Tired of the

Conservatory, he took advantage of the opportunity to go abroad in 1928

for the Schubert centenary celebrations in Vienna. He did not return.Maximilian Steinberg ran the Conservatory in his absence until Glazunov finally resigned in 1930.

Glazunov toured Europe and the United States, and settled in Paris. He

always claimed that the reason for his continued absence from Russia

was "ill health"; this enabled him to remain a respected composer in

the Soviet Union, unlike Stravinsky and Rachmaninoff,

who had left for other reasons. In 1929, he conducted an orchestra of

Parisian musicians in the first complete electrical recording of The Seasons. In 1934 he wrote his Saxophone Concerto. In 1929, at age 64, Glazunov married the 54-year-old Olga Nikolayevna Gavrilova (1875–1968). The

previous year, Olga's daughter Elena Gavrilova had been the soloist in

the first Paris performance of his Piano Concerto No. 2 in B major,

Op. 100. He

subsequently adopted Elena (she is sometimes referred to as his

stepdaughter), and she then used the name Elena Glazunova. In 1928,

Elena had married the pianist Sergei Tarnowsky, who managed Glazunov's professional and business affairs in Paris, such as negotiating his United States appearances with Sol Hurok. Elena later appeared as Elena Gunther-Glazunova after her second marriage, to Herbert Gunther (1906–1978). Glazunov

died in Paris at the age of 70 in 1936. The announcement of his death

shocked many. They had long associated Glazunov with the music of the

past rather than of the present, so they thought he had already been

dead for many years. In 1972 his remains were reinterred in Leningrad.