<Back to Index>

- Explorer James Weddell, 1787

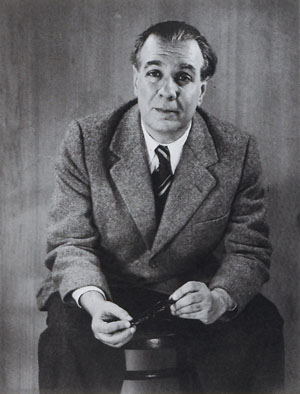

- Writer Jorge Luis Borges, 1899

- King of the Netherlands William I Frederick, 1772

Jorge Francisco Isidoro Luis Borges Acevedo (August 24, 1899 – June 14, 1986), best known as Jorge Luis Borges, was an Argentine writer, essayist, and poet born in Buenos Aires. In 1914 his family moved to Switzerland where he attended school and traveled to Spain. On his return to Argentina in 1921, Borges began publishing his poems and essays in surrealist literary journals. He also worked as a librarian and public lecturer. In 1955 he was appointed director of the National Public Library (Biblioteca Nacional) and professor of Literature at the University of Buenos Aires. In 1961 he came to international attention when he received the first International Publishers' Prize, the Prix Formentor. His work was translated and published widely in the United States and in Europe. Borges himself was fluent in several languages. He died in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1986.

His work embraces the "chaos that rules the world and the character of unreality in all literature." His most famous books, Ficciones (1944) and The Aleph (1949), are compilations of short stories interconnected by common themes: dreams, labyrinths, libraries, fictional writers and works, religion, God. His works have contributed significantly to the genre of magical realism. Scholars have noted that Borges's progressive blindness helped him to create

innovative literary symbols through imagination since "poets, like the

blind, can see in the dark". The poems of his late period dialogue with such cultural figures as Spinoza, Luís de Camões, and Virgil. His international fame was consolidated in the 1960s, aided by the "Latin American Boom" and the success of Gabriel García Márquez's Cien Años de Soledad. Writer and essayist J.M. Coetzee said

of him: "He, more than anyone, renovated the language of fiction and

thus opened the way to a remarkable generation of Spanish American

novelists." Jorge

Luis Borges was born to an educated middle-class family. Borges's

mother, Leonor Acevedo Suárez, came from a traditional Uruguayan family. His 1929 book Cuaderno San Martín included a poem "Isidoro Acevedo," commemorating his maternal grandfather, Isidoro de Acevedo Laprida, a soldier of the Buenos Aires Army who stood against dictator Juan Manuel de Rosas. A descendant of the Argentine lawyer and politician Francisco Narciso de Laprida, Acevedo fought in the battles of Cepeda in 1859, Pavón in 1861, and Los Corrales in

1880. Isidoro de Acevedo Laprida died of pulmonary congestion in the

house where his grandson Jorge Luis Borges was born. Borges's father,

Jorge Guillermo Borges Haslam, was a lawyer and psychology teacher

with literary aspirations. ("...he tried to become a writer and failed

in the attempt," Borges once said, "...[but] composed some very good sonnets"). His father was part Spanish, part Portuguese, and half English;

his paternal grandmother was English and maintained a strong spirit of

English culture in Borges's home. In this home, both Spanish and

English were spoken. From earliest childhood Borges was bilingual,

reading Shakespeare in English at the age of twelve. The family lived

in a large house with an English library of over one thousand volumes.

Borges would later remark that "if I were asked to name the chief event

in my life, I should say my father's library". They

were in comfortable circumstances; but not being wealthy enough to live

in downtown Buenos Aires, they resided in Palermo, then a poorer suburb

of the city. His

father was forced to give up practicing law due to the failing eyesight

that would eventually afflict his son. In 1914 the family moved to Geneva, Switzerland. Borges senior was treated by a Geneva eye specialist, while his son and daughter Norah attended school, where Borges junior learned French and taught himself German. He received his baccalauréat from the Collège de Genève in

1918. The Borges family decided that, due to political unrest in

Argentina, they would remain in Switzerland. This lasted until 1921

when, after World War I, the family spent three years living in various cities: Lugano, Barcelona, Majorca, Seville, and Madrid. At that time Borges discovered the writing of Arthur Schopenhauer and Gustav Meyrink's The Golem (1915) which became influential to his work. In Spain, Borges became a member of the avant-garde Ultraist literary movement (anti-Modernism, which ended in 1922 with the cessation of the journal Ultra). His first poem, "Hymn to the Sea", written in the style of Walt Whitman, was published in the magazine Grecia. While in Spain, he met noted Spanish writers, including Rafael Cansinos Assens and Ramón Gómez de la Serna. In 1921 Borges returned with his family to Buenos Aires, where he imported the doctrine of Ultraism and

launched his career, publishing surreal poems and essays in literary

journals. In 1930 Nestor Ibarra called Borges the "Great Apostle of

Criollismo." His first published collection of poetry was Fervor de Buenos Aires (1923). He contributed to the avant-garde review Martín Fierro (whose "art for art's sake" approach contrasted to that of the more politically involved Boedo group). Borges co-founded the journals Prisma, a broadsheet distributed largely by pasting copies to walls in Buenos Aires, and Proa.

Later in life Borges regretted some of these early publications, and

attempted to purchase all known copies to ensure their destruction. By the mid-1930s, he began to explore existential questions. He also worked in a style that Ana María Barrenechea has called "irreality." Borges was not alone in this task. Many other Latin American writers, such as Juan Rulfo, Juan José Arreola, and Alejo Carpentier, investigated these themes, influenced by the phenomenology of Husserl and Heidegger or the existentialism of Jean-Paul Sartre.

Even though existentialism saw its apogee during the years of Borges's

greatest artistic production, it can be argued that his choice of

topics largely ignored existentialism's central tenets. From the first issue, Borges was a regular contributor to Sur, founded in 1931 by Victoria Ocampo. It was then Argentina's most important literary journal. Ocampo introduced Borges to Adolfo Bioy Casares,

another well-known figure of Argentine literature, who was to become a

frequent collaborator and dear friend. Together they wrote a number of

works, some under the nom de plume H. Bustos Domecq, including a parody

detective series and fantasy stories. During these years a family friend Macedonio Fernández became

a major influence on Borges. The two would preside over discussions in

cafés, country retreats, or Fernández' tiny apartment in

the Balvanera district. In 1933 Borges gained an editorial appointment at the literary supplement of the newspaper Crítica, where he first published the pieces later collected as the Historia universal de la infamia (A Universal History of Infamy).

This involved two types of pieces. The first lay somewhere between

non-fictional essays and short stories, using fictional techniques to

tell essentially true stories. The second consisted of literary

forgeries, which Borges initially passed off as translations of

passages from famous but seldom-read works. In the following years, he

served as a literary adviser for the publishing house Emecé Editores and wrote weekly columns for El Hogar,

which appeared from 1936 to 1939. In

1937, Borges found work as first assistant at the Miguel Cané

branch of the Buenos Aires Municipal Library. His fellow employees

forbade him from cataloguing more than one hundred books per day, a

task which took him about an hour. The rest of his time he spent in the

basement of the library, writing articles and short stories. Borges's

urbane character allowed him to free himself from the trap of local

color. The varying genealogies of characters, settings, and themes in

his stories, such as "La muerte y la brújula", used Argentine

models without pandering to his readers. In his essay "El escritor

argentino y la tradición", Borges notes that the very absence of

camels in the Qur'an was proof enough that it was an Arabian work.

He suggested that only someone trying to write an "Arab" work would

purposefully include a camel. He uses this example to illustrate how

his dialogue with universal existential concerns was just as Argentine

as writing about gauchos and tangos (subjects he himself used). Borges's father died in 1938, a tragedy for the writer, as father and son were very devoted to each other. On Christmas Eve of the same year, Borges suffered a severe head wound; during treatment, he nearly died of septicemia.

While recovering from the accident, Borges began tinkering with a new

style of writing, for which he would become famous. The first story

penned after his accident was "Pierre Menard, Author of The Quixote" in May 1939. In this story, he examined the relationship between father and son and the nature of authorship. His first collection of short stories, El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan (The Garden of Forking Paths) appeared in 1941, composed mostly of works previously published in Sur. Though generally well received, El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan failed

to garner for him the literary prizes many in his circle expected.

Ocampo dedicated a large portion of the July 1941 issue of Sur to

a "Reparation for Borges"; numerous leading writers and critics from

Argentina and throughout the Spanish-speaking world contributed writings to the "reparation" project. The title story is about a

Chinese professor in England named Dr. Yu Tsun who spies for Germany

during World War I in an attempt to prove to the authorities that an

Asian person is able to obtain the information that they seek. When Juan Perón became

President in 1946, Borges was dismissed from the library and "promoted"

to the position of poultry inspector for the Buenos Aires municipal

market. (He immediately resigned; he always referred to this post as

"Poultry and Rabbit Inspector"). His offenses against the Peronistas up to that time consisted of little more than adding his signature to pro-democracy petitions. Shortly after his resignation, Borges addressed the Argentine Society of Letters saying,

in his characteristic style, "Dictatorships foster oppression,

dictatorships foster servitude, dictatorships foster cruelty; more

abominable is the fact that they foster idiocy." With his vision beginning to fade in his early thirties and unable to support himself as a writer, Borges began a new career as a public lecturer. Despite a certain degree of political persecution,

he was reasonably successful. Borges became an increasingly public

figure, obtaining appointments as President of the Argentine Society of

Writers, and as Professor of English and American Literature at the

Argentine Association of English Culture. His short story "Emma Zunz"

was turned into a film (under the name of Días de odio (English title: Days of Hate), directed in 1954 by the Argentine director Leopoldo Torre Nilsson). Around this time, Borges also began writing screenplays. In 1955 after the initiative of Ocampo, the new anti-Peronist military government appointed Borges head of the National Library. By that time, he had become completely blind, like one of his best known predecessors, Paul Groussac, for whom Borges wrote an obituary. Neither coincidence nor the irony escaped Borges and he commented on them in his work: The following year Borges was awarded the National Prize for Literature from the University of Cuyo, and the first of many honorary doctorates. From 1956 to 1970, Borges also held a position as a professor of literature at the University of Buenos Aires, while frequently holding temporary appointments at other universities. As

his eyesight deteriorated, Borges relied increasingly on his mother's

help. When he was not able to read and write anymore (he never learned

to read Braille), his mother, to whom he had always been devoted, became his personal secretary. When

Perón returned from exile and was re-elected president in 1973,

Borges immediately resigned as director of the National Library. In

1967 Borges married the recently widowed Elsa Astete Millán.

Friends believed that his mother, who was 90 and anticipating her own

death, wanted to find someone to care for her blind son. The marriage lasted

less than three years. After a legal separation, Borges moved back in

with his mother, with whom he lived until her death at age 99. Thereafter, he lived alone in the small flat he had shared with her, cared for by Fanny, their housekeeper of many decades. From

1975 until the time of his death, Borges traveled all over the world.

He was often accompanied in these travels by his personal assistant María Kodama,

an Argentine woman of Japanese and German ancestry. In April 1986, a

few months before his death, he married her via an attorney in Paraguay. Jorge Luis Borges died of liver cancer in 1986 in Geneva. He was buried in the Cimetière des Rois (Plainpalais).

After years of legal wrangling about the legality of the marriage,

Kodama, as sole inheritor of a significant annual income, gained

control over his works. Her administration of his estate has bothered

some scholars; she has been denounced by the French publisher Gallimard, by Le Nouvel Observateur, and by intellectuals such as Beatriz Sarlo, as an obstacle to the serious reading of Borges's works. Under Kodama, the Borges estate rescinded all publishing rights for existing

collections of his work in English (including the translations by Norman Thomas di Giovanni,

in which Borges himself cooperated — and from which di Giovanni received

fifty percent of the royalties) and commissioned new translations by Andrew Hurley. Eight of Borges's poems appear in the authoritative 1943 anthology of Spanish American Poets by H. R. Hays. One of Borges's stories was first translated into English in the August 1948 issue of Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine; the story was "The Garden of Forking Paths", the translator Anthony Boucher. Though several other Borges translations appeared in literary magazines and anthologies during the 1950s, his international fame dates from the early 1960s. In 1961 he received the first International Publishers' Prize, the Prix Formentor, which he shared with Samuel Beckett.

While Beckett had garnered a distinguished reputation in Europe and

America, Borges was unknown and untranslated in the English-speaking

world and the prize stirred interest in his work. The Italian

government named Borges Commendatore and the University of Texas at Austin appointed

him for one year to the Tinker Chair. This led to his first lecture

tour in the United States. In 1962 two major anthologies of Borges's

writings were published in English by New York presses: Ficciones and Labyrinths. In that year, Borges began lecture tours of Europe. In 1980 he was awarded the Balzan Prize (for Philology, Linguistics and literary Criticism) and the Prix mondial Cino Del Duca; numerous other honors were to accumulate over the years, such as the French Legion of Honour in 1983, the Cervantes Prize, and even a Special Edgar Allan Poe Award from the Mystery Writers of America, "for distinguished contribution to the mystery genre". In 1967 Borges began a five-year period of collaboration with the American translator Norman Thomas di Giovanni, thanks to whom he became better known in the English-speaking world. He also continued to publish books, among them El libro de los seres imaginarios (The Book of Imaginary Beings, (1967), co-written with Margarita Guerrero), El informe de Brodie (Dr. Brodie's Report, 1970), and El libro de arena (The Book of Sand, 1975). He also lectured prolifically. Many of these lectures were anthologized in volumes such as Siete noches (Seven Nights) and Nueve ensayos dantescos (Nine Dantesque Essays). In The New Media Reader, editors Wardrip-Fruin and Montfort argued

that Borges "may have been the most important figure in

Spanish-language literature since Cervantes. But whatever his

particular literary rank, he was clearly of tremendous influence,

writing intricate poems, short stories, and essays that instantiated

concepts of dizzying power." According

to the editors, Borges represented the humanist view of digital media

that stressed the social aspect of art driven by emotion. If art

represented the tool, then humanists like Borges were more interested

about how the tool could be used to relate to people rather than how it

could help future generations. For engineers like Vannevar Bush, bettering the future was considered a more scientific view of digital media. Borges's change in style from criollismo to a more cosmopolitan style brought him much criticism from journals such as Contorno, a left-of-center, Sartre-influenced publication founded by the Viñas brothers (Ismael & David), Noé Jitrik, Adolfo Prieto, and other intellectuals. Contorno "met

with wide approval among the youth [...] for taking the older writers

of the country to task on account of [their] presumed inauthenticity

and their legacy of formal experimentation at the expense of

responsibility and seriousness in the face of society's problems". Borges

and Eduardo Mallea were criticized for being "doctors of technique";

their writing presumably "lacked substance due to their lack of

interaction with the reality [...] that they inhabited", an existential

critique of their refusal to embrace existence and reality in their

artwork. Borges was never awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, something which continually distressed the writer. He was one of several distinguished authors who never received the honor. Some observers speculated that Borges did not receive the award because of his conservative political views, more specifically, that he accepted an honor from dictator Augusto Pinochet.