<Back to Index>

- Philosopher John Locke, 1632

- Painter Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, 1780

- Controller General of Finances Jean Baptiste Colbert, 1619

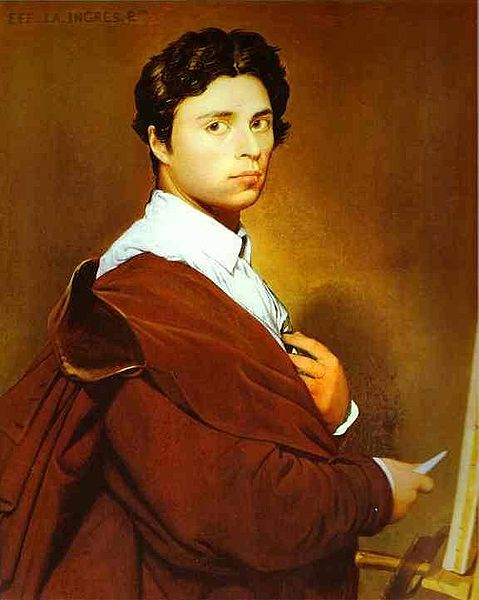

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (29 August 1780 – 14 January 1867) was a French Neoclassical painter. Although he considered himself to be a painter of history in the tradition of Nicolas Poussin and Jacques-Louis David, by the end of his life it was Ingres's portraits, both painted and drawn, that were recognized as his greatest legacy.

A man profoundly respectful of the past, he assumed the role of a guardian of academic orthodoxy against the ascendant Romantic style represented by his nemesis Eugène Delacroix. His exemplars, he once explained, were "the great masters which flourished in that century of glorious memory when Raphael set the eternal and incontestable bounds of the sublime in art ... I am thus a conservator of good doctrine, and not an innovator." Nevertheless,

modern opinion has tended to regard Ingres and the other Neoclassicists

of his era as embodying the Romantic spirit of his time, while his expressive distortions of form and space make him an important precursor of modern art. Ingres was born in Montauban, Tarn-et-Garonne,

France, the first of seven children (five of whom survived infancy) of

Jean- Marie-Joseph Ingres (1755 – 1814) and his wife Anne Moulet (1758

– 1817). His father was a successful jack-of-all-trades in the arts, a

painter of miniatures,

sculptor, decorative stonemason, and amateur musician; his mother was

the nearly illiterate daughter of a master wigmaker. From his father

the young Ingres received early encouragement and instruction in

drawing and music, and his first known drawing, a study after an

antique cast, was made in 1789. Starting

in 1786 he attended the local school, Ecole des Frères de

l'Education Chrétienne, but his education was disrupted by the

turmoil of the French Revolution,

and the closing of the school in 1791 marked the end of his

conventional education. The deficiency of his schooling would always

remain for him a source of insecurity. In 1791, Joseph Ingres took his son to Toulouse,

where the young Jean Auguste Dominique was enrolled in the

Académie Royale de Peinture, Sculpture et Architecture. There he

studied under the sculptor Jean-Pierre Vigan, the landscape painter

Jean Briant, and — most importantly — the painter Joseph Roques, who imparted to the young artist his veneration of Raphael. Ingres's

musical talent was further developed under the tutelage of the

violinist Lejeune. From the ages of thirteen to sixteen he was second

violinist in the Orchestre du Capitole de Toulouse, and he would

continue to play the violin as an avocation for the rest of his life. Having been awarded first prize in drawing by the Academy, in August 1797 he traveled to Paris to study with Jacques-Louis David,

France's — and Europe's — leading painter during the revolutionary

period, in whose studio he remained for four years. Ingres followed his

master's neoclassical example but revealed, according to David, "a

tendency toward exaggeration in his studies." He was admitted to the Painting Department of the École des Beaux-Arts in October 1799, and won, after tying for second place in 1800, the Grand Prix de Rome in 1801 for his Ambassadors of Agamemnon in the tent of Achilles.

His trip to Rome, however, was postponed until 1806, when the

financially strained government finally appropriated the travel funds. Working

in Paris alongside several other students of David in a studio provided

by the state, he further developed a style that emphasized purity of

contour. He found inspiration in the works of Raphael, in Etruscan vase paintings, and in the outline engravings of the English artist John Flaxman. In 1802 he made his debut at the Salon with Portrait of a Woman (the

current whereabouts of which are unknown). The following year brought a

prestigious commission, when Ingres was one of five artists selected

(along with Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Robert Lefèvre, Charles Meynier, and Marie-Guillemine Benoist) to paint full-length portraits of Napoleon Bonaparte as First Consul. These were to be distributed to the prefectural towns of Liège, Antwerp, Dunkerque, Brussels, and Ghent, all of which were newly ceded to France in the 1801 Treaty of Lunéville. In the summer of 1806 Ingres became engaged to Marie-Anne-Julie Forestier, a painter and musician, before leaving for Rome in

September. Although he had hoped to stay in Paris long enough to

witness the opening of that year's Salon, in which he was to display

several works, he reluctantly left for Italy just days before the

opening. At the Salon, his paintings — Self-Portrait, portraits of the Rivière family, and Napoleon I on his Imperial Throne — produced a disturbing impression on the public, due not only to Ingres's stylistic idiosyncrasies but also to his adoption of Carolingian imagery in representing Napoleon. David delivered a severe judgement, and

the critics were uniformly hostile, finding fault with the strange

discordances of colour, the want of sculptural relief, the chilly

precision of contour, and the self-consciously archaic quality. Chaussard (Le Pausanias Français, 1806) condemned Ingres's style as gothic and asked: How,

with so much talent, a line so flawless, an attention to detail so

thorough, has M. Ingres succeeded in painting a bad picture? The answer

is that he wanted to do something singular, something

extraordinary ... M. Ingres's intention is nothing less than to

make art regress by four centuries, to carry us back to its infancy, to

revive the manner of Jean de Bruges. As

art historian Marjorie Cohn has written: "At the time, art history as a

scholarly enquiry was brand new. Artists and critics outdid each other

in their attempts to identify, interpret, and exploit what they were

just beginning to perceive as historical stylistic developments." The Louvre, newly filled with booty seized by Napoleon in his campaigns in Belgium, Holland, and Italy,

provided French artists of the early nineteenth century with an

unprecedented opportunity to study, compare, and copy masterworks from

antiquity and from the entire history of European painting. From

the beginning of his career, Ingres freely borrowed from earlier art,

adopting the historical style appropriate to his subject, leading

critics to charge him with plundering the past. Newly

arrived in Rome, Ingres read with mounting indignation the relentlessly

negative press clippings sent to him from Paris by his friends. In

letters to his prospective father-in-law he expressed his outrage at

the critics: "So the Salon is the scene of my disgrace; ... The

scoundrels, they waited until I was away to assassinate my

reputation ... I have never been so unhappy." He vowed never again

to exhibit at the Salon, and his refusal to return to Paris led to the

breaking up of his engagement. Julie

Forestier, when asked years later why she had never married, responded,

"When one has had the honor of being engaged to M. Ingres, one does not

marry." Installed in a studio on the grounds of the Villa Medici, Ingres continued his studies and, as required of every winner of the Prix, he sent works at regular intervals to Paris so his progress could be judged. As his envoi of 1808 Ingres sent Oedipus and the Sphinx and the Valpinçon Bather (both now in the Louvre), hoping by these two paintings to demonstrate his mastery of the male and female nude, but they were poorly received. In later years Ingres painted variants of both compositions; another nude begun in 1807, the Venus Anadyomene, remained in an unfinished state for decades, to be completed forty years later and finally exhibited in 1855. He produced numerous portraits during this period: Madame Duvauçay, François-Marius Granet, Edme-François-Joseph Bochet, Madame Panckoucke, and that of Madame la Comtesse de Tournon, mother of the prefect of the department of the Tiber.

In 1810 Ingres's pension at the Villa Medici ended, but he decided to

stay in Rome and seek patronage from the French occupation government.

In 1811 Ingres finished his final student exercise, the immense Jupiter and Thetis, which was once again harshly judged in Paris. Ingres was stung; the public was indifferent, and the strict classicists among his fellow artists looked upon him as a renegade. Only Eugène Delacroix and other pupils of Pierre-Narcisse Guérin —

the leaders of that romantic movement for which Ingres throughout his

long life always expressed the deepest abhorrence — seem to have

recognized his merits. Although

facing uncertain prospects, in 1813 Ingres married a young woman,

Madeleine Chapelle, who had been recommended to him by her friends in

Rome. After a courtship carried out through correspondence, he proposed

to her without having met her, and she accepted. Their marriage was a

happy one, and Madame Ingres acquired a faith in her husband which

enabled her to combat with courage and patience the difficulties of

their common existence. He continued to suffer the indignity of

disparaging reviews, as Don Pedro of Toledo Kissing the Sword of Henry IV, Raphael and the Fornarina (Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University), several portraits, and the Interior of the Sistine Chapel met a generally hostile critical response at the Paris Salon of 1814. A few important commissions came to him; the French governor of Rome asked him to paint Virgil reading the Aeneid (1812) for his residence, and to paint two colossal works — Romulus's victory over Acron (1812) and The Dream of Ossian (1813) — for Monte Cavallo,

a former Papal residence undergoing renovation to become Napoleon's

Roman palace. These paintings epitomized, both in subject and scale,

the type of painting with which Ingres was determined to make his

reputation, but, as Philip Conisbee has pointed out, "for all the high

ideals that had been drummed into Ingres at the academies in Toulouse,

Paris, and Rome, such commissions were exceptions to the rule, for in

reality there was little demand for history paintings in the grand

manner, even in the city of Raphael and Michelangelo." Art

collectors preferred "light-hearted mythologies, recognizable scenes of

everyday life, landscapes, still lifes, or likenesses of men and women

of their own class. This preference persisted throughout the nineteenth

century, as academically oriented artists waited and hoped for the

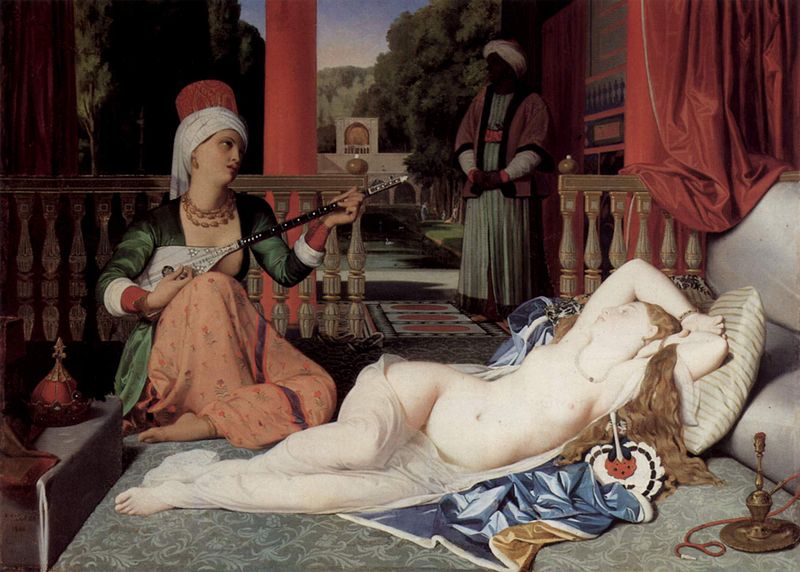

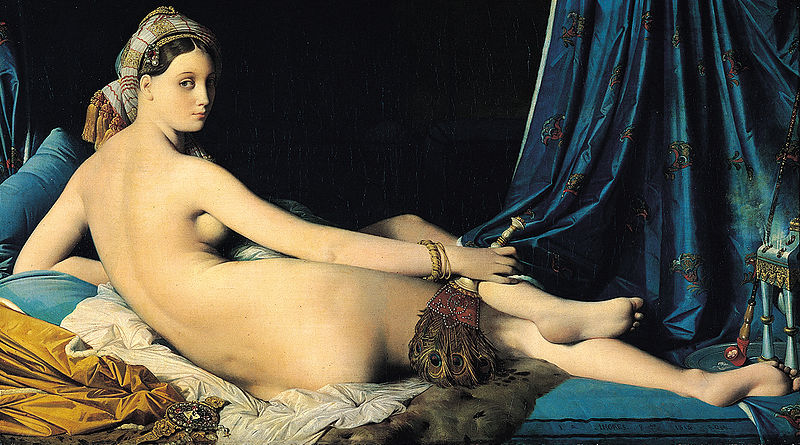

patronage of state or church to satisfy their more elevated ambitions." Ingres traveled to Naples in the spring of 1814 to paint Queen Caroline Murat, and the Murat family ordered additional portraits as well as three modestly-scaled works: The Betrothal of Raphael, La Grande Odalisque, and Paolo and Francesca. He never received payment for these paintings, however, due to the collapse of the Murat regime in 1815; with the fall of Napoleon's dynasty, he found himself essentially stranded in Rome without patronage. During

this low point of his career, Ingres was forced to depend for his

livelihood on the execution, in pencil, of small portrait drawings of

the many tourists, in particular the English, passing through postwar

Rome. For an artist who aspired to a reputation as a history painter,

this seemed menial work, and to the visitors who knocked on his door

asking, "Is this where the man who draws the little portraits lives?",

he would answer with irritation, "No, the man who lives here is a

painter!" Nevertheless, the

portrait drawings he produced in such profusion during this period are

of outstanding quality, and rank today among his most admired works. Mining the vein of the small-scale historical genre piece, in 1815 he painted Aretino and the Envoy of Charles V as well as Aretino and Tintoretto,

an anecdotal painting whose subject, a painter brandishing a pistol at

his critic, may have been especially satisfying to the embattled Ingres. In 1817 he painted Henry IV Playing with His Children, and in the following year the Death of Leonardo. In 1817 the Count of Blacas, who was ambassador of France to the Holy See, provided Ingres with his first official commission since 1814, for a painting of Christ Giving the Keys to Peter.

Completed in 1820, this imposing work was well-received in Rome but to

the artist's chagrin the ecclesiastical authorities there would not

permit it to be sent to Paris for exhibition. A commission came in 1816 or 1817 from the family of the celebrated Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, Duke of Alva, for a painting of the Duke receiving papal honors for his repression of the Protestant Reformation.

Ingres, despite his distaste for the subject and his loathing for the

man he described as "cet horrible homme", made sketches for this

project which reveal his attempt to fulfill the commission while

conveying his disapproval. Finally

he abandoned the task and entered in his diary, "J'etais forcé

par la necessité de peindre un pareil tableau; Dieu a voulu

qu'il reste en ebauche." ("I was forced by need to paint such a

painting; God wanted it to remain a sketch.") During this period, Ingres formed friendships with musicians including Paganini, and regularly played the violin with others who shared his enthusiasm for Mozart, Haydn, Gluck, and Beethoven. The works he sent to the 1819 Salon were La Grande Odalisque, Philip V and the Marshal of Berwick, and Roger Freeing Angelica, which were once again attacked as "gothic". Ingres and his wife moved to Florence in 1820 at the urging of the Florentine sculptor Lorenzo Bartolini,

an old friend from his years in Paris, who hoped that Ingres would

improve his position materially, but Ingres, as before, had to rely on

his drawings of tourists and diplomats for support. His friendship with

Bartolini, whose worldly success in the intervening years stood in

sharp contrast to Ingres's poverty, quickly became strained, and Ingres

found new quarters. In 1821 he finished a painting commissioned by a childhood friend, Monsieur de Pastoret, the Entry of Charles V into Paris; de Pastoret also ordered a portrait of himself and a religious work (Virgin with the Blue Veil).

The major undertaking of this period, however, was a commission

obtained in August 1820 with the help of de Pastoret, to paint the Vow of Louis XIII for

the Cathedral of Montauban. Recognizing this as an opportunity to

establish himself as a painter of history, he spent four diligent years

bringing the large canvas to completion, and he travelled to Paris with

it in October 1824. The Vow of Louis XIII, exhibited at the Salon of 1824, finally brought Ingres critical success. Conceived in a Raphaelesque style

relatively free of the archaisms for which he had been reproached in

the past, it was admired even by strict Davidians. Ingres found himself

celebrated throughout France; in January 1825 he was awarded the Cross

of the Légion d'honneur, and in June 1825 he was elected to the Institute. His fame was extended further in 1826 by the publication of Sudre's lithograph of La Grande Odalisque, which, having been scorned by artists and critics alike in 1819, now became widely popular. A commission from the government called forth the monumental Apotheosis of Homer, which Ingres eagerly finished in a year's time. From 1826 to 1834 the studio of Ingres was thronged, and he was a recognized chef d'école who

taught with authority and wisdom while working steadily. The critics

came to regard Ingres as the standard bearer of classicism against the

romantic school —

a role he relished. The paintings, primarily portraits, that he sent to

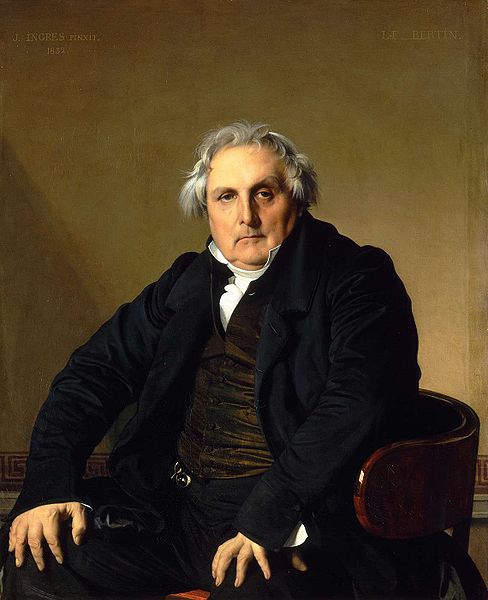

the Salon in 1827 and 1833 were well received. The portrait of Louis-François Bertin (1832)

was a particular success with the public, who found its realism

spellbinding, although some of the critics found its naturalism vulgar

and its coloring drab. The thin-skinned artist was outraged, however, by the criticism of his ambitious canvas of the Martyrdom of Saint Symphorien (cathedral of Autun),

shown in the Salon of 1834. Resentful and disgusted, Ingres resolved

never again to work for the public, and gladly availed himself of the

opportunity to return to Rome, as director of the École de

France, in the room of Horace Vernet. There, although the time he spent in administrative duties slowed the flow of paintings from his brush, he executed Antiochus and Stratonice (executed for Louis-Philippe, duc d'Orléans), Portrait of Luigi Cherubini, and the Odalisque with Slave, among other works. The Stratonice,

exhibited at the Palais Royal for several days after its arrival in

France, produced so favourable an impression that, on his return to

Paris in 1841, Ingres was received with all the deference that he felt

was his due. One of the first works executed after his return was a

portrait of the duc d'Orléans, whose death in a carriage

accident just weeks after the completion of the portrait sent the

nation into mourning and led to orders for additional copies of the

portrait. Ingres shortly afterward began the decorations of the great hall in the Chateau de Dampierre. These murals, the Golden Age and the Iron Age,

were begun in 1843 with an ardour which gradually slackened until

Ingres, devastated by the loss of his wife on 27 July 1849, abandoned

all hope of their completion and the contract with the Duc de Luynes

was finally cancelled. A minor work, Jupiter and Antiope,

dates from 1851; in July of that year he announced a gift of his

artwork to his native city of Montauban, and in October he resigned as

professor at the École des Beaux-Arts. The

following year Ingres, at seventy-one years of age, married

forty-three-year-old Delphine Ramel, a relative of his friend Marcotte

d'Argenteuil. This marriage proved as happy as his first, and in the

decade that followed Ingres completed several significant works. A

major undertaking was the Apotheosis of Napoleon I, painted in 1853 for the ceiling of a hall in the Hotel de Ville, Paris and destroyed by fire in the Commune of 1871. The portrait of Princesse Albert de Broglie was also completed in 1853, and Joan of Arc appeared

in 1854. The latter was largely the work of assistants, whom Ingres

often entrusted with the execution of backgrounds. In 1855 Ingres

consented to rescind his resolution, more or less strictly kept since

1834, in favour of the International Exhibition, where a room was

reserved for his works. Napoléon Joseph Charles Paul Bonaparte, president of the jury, proposed an exceptional recompense for their author, and obtained from emperor Napoleon III of France Ingres's nomination as grand officer of the Légion d'honneur. With renewed confidence Ingres now took up and completed one of his most charming productions, The Source,

a figure for which he had painted the torso in 1823; when seen with

other works in London in 1862, admiration for his works was renewed,

and he was given the title of senator by the imperial government. After the completion of The Source, Ingres produced paintings of historical genre, such as two versions of Louis XIV and Molière, (1857 and 1860), as well as several religious works in which the figure of the Virgin from The Vow of Louis XIII is reprised: The Virgin of the Adoption of 1858 (painted for Mademoiselle Roland-Gosselin) was followed by The Virgin Crowned (painted for Madame la Baronne de Larinthie) and The Virgin with Child. In 1859 he produced repetitions of The Virgin of the Host, and in 1862 he completed Christ and the Doctors, a work commissioned many years before by Queen Marie Amalie for the chapel of Bizy. The last of his important portrait paintings date from this period: Marie-Clothilde-Inés de Foucauld, Madame Moitessier, Seated (1856), Self-Portrait at the Age of Seventy-nine and Madame J.-A.-D. Ingres, née Delphine Ramel, both completed in 1859. The Turkish Bath, finished in a rectangular format in 1859, was revised in 1860 before being turned into a tondo. Ingres signed and dated it in 1862, although he made additional revisions in 1863. Ingres died of pneumonia on 17 January 1867, at the age of eighty-six, having preserved his faculties to the last. He is interred in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, France, with a tomb sculpted by his student Jean-Marie Bonnassieux.

The contents of his studio, including a number of major paintings, over

4000 drawings, and his violin, were bequeathed by the artist to the

city museum of Montauban, now known as the Musée Ingres.