<Back to Index>

- Chemist Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac, 1778

- Author Baldassare Castiglione, 1478

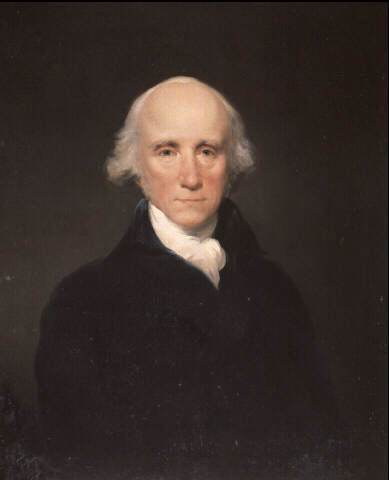

- 1st Governor General of Bengal Warren Hastings, 1732

PAGE SPONSOR

Warren Hastings (6 December 1732 – 22 August 1818) was the first Governor-General of India, from 1773 to 1785. He was famously accused of corruption in an impeachment in 1787, but was acquitted in 1795. He was made a Privy Councillor in 1814.

Warren Hastings was born at Churchill, Oxfordshire, in 1732 to a poor father and a mother who died soon after he was born. He attended Westminster School before joining the British East India Company in 1750 as a clerk. In 1757 he was made the British Resident (administrator in charge) of Murshidabad. He was appointed to the Calcutta council in 1761 and returned to England in 1764. He went back to India in 1769 as a member of the Madras council and was made governor of Bengal in 1772. In 1773, he was appointed the first Governor-General of India.

At the time of his appointment to the post of Governor-General of India,

the position was so new that the mechanisms by which the British would

administer the territory were still being developed. Hastings held the

title of governor, but rule was effected by a five man council on which

he was no more than a member. In fact, the organisational structure was

so confused that it "passed the wit of man to say what consitutional

position he occupied."

After an eventful ten-year tenure in which he greatly extended and regularised the nascent Raj created by Clive of India, Hastings resigned in 1784. On his return to England he was charged with high crimes and misdemeanours by Edmund Burke, encouraged by Sir Philip Francis whom he had wounded in a duel in India. He was impeached in 1787 but the trial, which began in 1788, ended with his acquittal in 1795. Hastings spent most of his fortune on his defence, although towards the end of the trial the East India Company did provide financial support.

He retained his supporters, however, and on 22 August 1806, the Edinburgh East India Club and a number of gentlemen from India gave what was described as "an elegant entertainment" to "Warren Hastings, Esq., late Governor-General of India", who was then on a visit to Edinburgh. One of the 'sentiments' drunk on the occasion was "Prosperity to our settlements in India, and may the virtue and talents which preserved them be ever remembered with gratitude."

In 1788 he acquired the estate at Daylesford, Gloucestershire,

including the site of the medieval seat of the Hastings family. In the

following years, he remodelled the mansion to the designs of Samuel Pepys Cockerell, with magnificent classical and Indian decoration, and gardens landscaped by John Davenport. He also rebuilt the Norman church in 1816, where he was buried two years later. During

the final quarter of the eighteenth century, many of the Company's

senior administrators realised that in order to govern Indian society,

it was essential that they learn its various religious, social, and

legal customs and precedents. The importance of such knowledge to the

colonial government was clearly in Hastings's mind when, in 1784, he

remarked that: “Every

application of knowledge and especially such as is obtained in social

communication with people, over whom we exercise dominion, founded on

the right of conquest, is useful to the state … It attracts and

conciliates distant affections, it lessens the weight of the chain by

which the natives are held in subjection and it imprints on the hearts

of our countrymen the sense of obligation and benevolence… Every

instance which brings their real character will impress us with more

generous sense of feeling for their natural rights, and teach us to

estimate them by the measure of our own… But such instances can only be

gained in their writings; and these will survive when British

domination in India shall have long ceased to exist, and when the

sources which once yielded of wealth and power are lost to remembrance” Under

Hastings's term as Governor General, a great deal of administrative

precedent was set which profoundly shaped later attitudes towards the

government of British India. Hastings had a great respect for the

ancient scripture of Hinduism and set the British position on governance as one of looking back to the earliest precedents possible. This allowed Brahmin advisors to mould the law, as no English person thoroughly understood Sanskrit until Sir William Jones,

and, even then, a literal translation was of little use; it needed to

be elucidated by religious commentators who were well-versed in the

lore and application. This approach accentuated the Hindu caste system

and, to an extent, the frameworks of other religions, which had, at

least in recent centuries, been somewhat more flexibly applied. Thus,

British influence on the fluid social structure of India can in large

part be characterised as a solidification of the privileges of the

Hindu caste system through the influence of the exclusively high-caste

scholars by whom the British were advised in the formation of their laws. In 1781, Hastings founded Madrasa 'Aliya, meaning the higher madrasa, at Calcutta in an attempt to conciliate the goodwill of the Muslim population. In addition, in 1784 Hastings supported the foundation of the Bengal Asiatic Society (now Asiatic Society of Bengal) by the oriental scholar Sir William Jones, which became a storehouse

for information and data pertaining to the subcontinent, and exists in

various institutional guises up to the present day. Hastings'

legacy has been somewhat dualistic as an Indian administrator, he

undoubtedly was able to institute reforms during the time he spent as

governor there that would change the path that India would follow over

the next several years. He did, however, retain the strange distinction

of being both the “architect of British India and the one ruler of

British India to whom the creation of such an entity was anathema." He was impeached for crimes and misdemeanours during his time in India in the House of Commons upon his return to England. At first deemed unlikely to succeed, the prosecution was managed by MPs including Edmund Burke, Charles James Fox and Richard Brinsley Sheridan. When the charges of his indictment were read, the twenty counts were so long that it took Edmund Burke two full days to read them. The house sat for a total of 148 days over a period of seven years during the investigation.

The investigation was pursued at great cost to Hastings personally, and

he complained constantly that the cost of defending himself from the

prosecution was bankrupting him. He is rumored to at one time have

stated that the punishment given him would have been less extreme had

he pleaded guilty. The House of Lords finally made its decision on April 1795 acquitting him on all charges. The city of Hastings, New Zealand and the Melbourne outer suburb of Hastings, Victoria, Australia were

both named after him. 'Hastings' is the name of one of the 4 School

Houses in La Martiniere for Boys, Calcutta. It is represented by the

colour red. 'Hastings' is a Senior Wing House at St Paul's School, Darjeeling, India,

where all the senior wing houses are named after Anglo-Indian colonial

figures. There is also a road in Kolkata, India named after him.