<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Jacques Salomon Hadamard, 1865

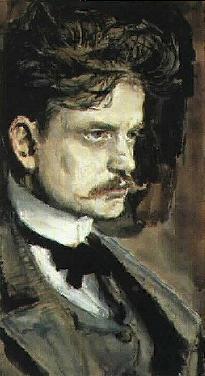

- Composer Johan Julius Christian Sibelius, 1865

- Holy Roman Emperor Francis I, 1708

PAGE SPONSOR

Jean Sibelius (8 December 1865 – 20 September 1957) was a Finnish composer of the later Romantic period whose music played an important role in the formation of the Finnish national identity.

The core of Sibelius's oeuvre is his set of seven symphonies. Like Beethoven,

Sibelius used each one to develop further his own personal

compositional style. Unlike Beethoven who used the symphonies to make

public statements, and who reserved his more intimate feelings for his

smaller works, Sibelius released his personal feelings in the

symphonies. These

works continue to be performed frequently in the concert hall and are

often recorded. In addition to the symphonies, Sibelius's best-known

compositions include Finlandia, Valse triste, the violin concerto, the Karelia Suite and The Swan of Tuonela (one of the four movements of the Lemminkäinen Suite). Other works include pieces inspired by the Kalevala, over 100 songs for voice and piano, incidental music for 13 plays, the opera Jungfrun i tornet (The Maiden in the Tower), chamber music, piano music, 21 separate publications of choral music, and Masonic ritual music. Sibelius composed prolifically until the mid-1920s. However, soon after completing his Seventh Symphony (1924), the incidental music to The Tempest (1926), and the tone poem Tapiola (1926),

he produced no large scale works for the remaining thirty years of his

life. Although he is reputed to have stopped composing, he did attempt

to continue writing, including abortive attempts to compose an eighth

symphony. He wrote some Masonic music and re-edited some earlier works

during this last period of his life, and retained an active interest in

new developments in music, although he did not always view modern music

favorably. The Finnish 100 mark bill featured his image. Johan Julius Christian Sibelius was born into a Swedish-speaking family in Hämeenlinna in the Russian Grand Duchy of Finland, the son of Christian Gustaf Sibelius and Maria Charlotta Sibelius.

Although known as "Janne" to his family, during his student years he

began using the French form of his name, "Jean", inspired by the

business card of his seafaring uncle. He is universally known as Jean Sibelius. Against the larger context of the rise of the Fennoman movement and its expressions of Romantic Nationalism, his family decided to send him to a Finnish language school, and he attended the Hämeenlinna Normal-Lycée from 1876 to 1885. Romantic Nationalism was to become a crucial element in Sibelius's artistic output and his politics. After Sibelius graduated from high school in 1885, he began to study law at the Imperial Alexander University of Finland (now

the University of Helsinki). However, he was more interested in music

than in law, and he soon quit his studies. From 1885 to 1889, Sibelius

studied music in the Helsinki music school (now the Sibelius Academy). One of his teachers there was Martin Wegelius. Sibelius continued studying in Berlin (from 1889 to 1890) and in Vienna (from 1890 to 1891). Jean Sibelius married Aino Järnefelt (1871 – 1969) at Maxmo on 10 June 1892. Their home, called Ainola, was completed at Lake Tuusula, Järvenpää in

1903, and the two lived out the remainder of their lives there. They

were married for 64 years and had six daughters: Eva, Ruth, Kirsti (who

died at a very young age), Katarina, Margareta, and Heidi. In 1911, Sibelius underwent a serious operation for suspected throat cancer. The impact of this brush with death can be seen in several of the works that he composed at the time, including Luonnotar and the Fourth Symphony. Sibelius loved nature, and the Finnish landscape often served as material for his music. He once said of his Sixth Symphony,

"[It] always reminds me of the scent of the first snow." The forests

surrounding Ainola are often said to have inspired his composition of Tapiola. On the subject of Sibelius's ties to nature, one biographer of the composer, Erik Tawaststjerna, wrote the following: The year 1926 saw a sharp and lasting decline in Sibelius's output: after his Seventh Symphony, he only produced a few major works in the rest of his life. Arguably the two most significant were incidental music for Shakespeare's The Tempest and the tone poem Tapiola.

For nearly the last thirty years of his life, Sibelius even avoided

talking about his music. There is substantial evidence that Sibelius

worked on an eighth numbered symphony. He promised the premiere of this symphony to Serge Koussevitzky in 1931 and 1932, and a London performance in 1933 under Basil Cameron was

even advertised to the public. However, the only concrete evidence for

the symphony's existence on paper is a 1933 bill for a fair copy of the

first movement. Sibelius had always been quite self-critical; he remarked to his close friends,

"If I cannot write a better symphony than my Seventh, then it shall be

my last." Since no manuscript survives, sources consider it likely that

Sibelius destroyed all traces of the score, probably in 1945, during

which year he certainly consigned (in his wife's presence) a great many

papers to the flames. On January 1, 1939, Sibelius participated in an international radio broadcast which included the composer conducting his Andante Festivo.

The performance was preserved on transcription discs and later issued

on CD. This is probably the only surviving example of Sibelius

interpreting his own music. His 90th birthday, in 1955, was widely celebrated and both the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra under Sir Thomas Beecham gave

special performances of his music in Finland. The orchestras and their

conductors also met the composer at his home; a series of memorable

photographs were taken to commemorate the occasions. Both Columbia

Records and EMI released some of the pictures with albums of Sibelius's

music. Beecham was honored by the Finnish government for his efforts to

promote Sibelius both in the United Kingdom and in the United States. Tawaststjerna also relayed an endearing anecdote regarding Sibelius's death: In 1972, Sibelius's surviving daughters sold Ainola to the State of Finland. The Ministry of Education and the Sibelius Society opened it as a museum in 1974. Like many of his contemporaries, Sibelius was initially enamored with the music of Wagner. A performance of Parsifal at the Bayreuth Festival had

a strong effect on him, inspiring him to write to his wife shortly

thereafter, "Nothing in the world has made such an impression on me, it

moves the very strings of my heart." He studied the scores of Wagner's

operas Tannhäuser, Lohengrin, and Die Walküre intently. With this music in mind, Sibelius began work on an opera of his own, entitled Veneen luominen (The Building of the Boat). However, his appreciation for Wagner waned and Sibelius ultimately rejected Wagner's Leitmotif compositional

technique, considering it to be too deliberate and calculated.

Departing from opera, he later used the musical material from the

incomplete Veneen luominen in his Lemminkäinen Suite (1893). He did, however, compose a considerable number of songs for voice and piano, whose early interpreters included Aino Ackté and particularly Ida Ekman. More lasting influences included Ferruccio Busoni, Anton Bruckner and Tchaikovsky. Hints of Tchaikovsky's music are particularly evident in works such as Sibelius's First Symphony (1899) and his Violin Concerto (1905).

Similarities to Bruckner are most strongly felt in the 'unmixed'

timbral palette and sombre brass chorales of Sibelius's orchestration,

as well as in the latter composer's fondness for pedal points and in

the underlying slow pace of his music. Sibelius progressively stripped away formal markers of sonata form in

his work and, instead of contrasting multiple themes, he focused on the

idea of continuously evolving cells and fragments culminating in a

grand statement. His later works are remarkable for their sense of

unbroken development, progressing by means of thematic permutations and

derivations. The completeness and organic feel of this synthesis has

prompted some to suggest that Sibelius began his works with a finished

statement and worked backwards, although analyses showing these

predominantly three- and four-note cells and melodic fragments as they

are developed and expanded into the larger "themes" effectively prove

the opposite. This self-contained structure stood in stark contrast to the symphonic style of Gustav Mahler,

Sibelius's primary rival in symphonic composition. While thematic

variation played a major role in the works of both composers, Mahler's

style made use of disjunct, abruptly changing and contrasting themes,

while Sibelius sought to slowly transform thematic elements. In

November 1907 Mahler undertook a conducting tour of Finland, and the

two composers had occasion to go on a lengthy walk together. Sibelius later reported that during the walk: However,

the two rivals did find common ground in their music. Like Mahler,

Sibelius made frequent use both of folk music and of literature in the

composition of his works. The Second Symphony's slow movement was sketched from the motive of Il Commendatore in Don Giovanni, while the stark Fourth Symphony combined work for a planned "Mountain" symphony with a tone poem based on Edgar Allan Poe's "The Raven". Sibelius also wrote several tone poems based on Finnish poetry, beginning with the early En Saga and culminating in the late Tapiola (1926), his last major composition. Over time, he sought to use new chord patterns, including naked tritones (for example in the Fourth Symphony), and bare melodic structures to build long movements of music, in a manner similar to Joseph Haydn's use of built-in dissonances. Sibelius would often alternate melodic sections with noble brasschords

that would swell and fade away, or he would underpin his music with

repeating figures which push against the melody and counter-melody. Sibelius's melodies often feature powerful modal implications: for example much of the Sixth Symphony is in the (modern) Dorian mode. Sibelius studied Renaissance polyphony, as did his contemporary, the Danish composer Carl Nielsen,

and Sibelius's music often reflects the influence of this early music.

He often varied his movements in a piece by changing the note values of

melodies, rather than the conventional change of tempi.

He would often draw out one melody over a number of notes, while

playing a different melody in shorter rhythm. For example, his Seventh Symphony comprises

four movements without pause, where every important theme is in C major

or C minor; the variation comes from the time and rhythm. His harmonic

language was often restrained, even iconoclastic, compared to many of

his contemporaries who were already experimenting with musical

Modernism. Because

of its alleged conservatism, Sibelius's music is sometimes considered

insufficiently complex, but he was immediately respected by even his

more progressive peers. Later in life he was championed by critic Olin Downes, who wrote a biography, but he was attacked by composer-critic Virgil Thomson. Sibelius has sometimes been criticized as a reactionary or even incompetent figure in 20th century classical music. In 1938 Theodor Adorno wrote a critical essay about the composer, notoriously charging that Composer and theorist René Leibowitz went so far as to describe Sibelius as "the worst composer in the world" in the title of a 1955 pamphlet. Despite the innovations of the Second Viennese School, he continued to write in a strictly tonal idiom.

However, critics who have sought to re-evaluate Sibelius's music have

cited its self-contained internal structure, which distills everything

down to a few motivic ideas and then permits the music to grow

organically, as evidence of a previously under-appreciated radical bent

to his work. The severe nature of Sibelius's orchestration is often

noted as representing a "Finnish" character, stripping away the

superfluous from music. Perhaps

one reason Sibelius has attracted both the praise and the ire of

critics is that in each of his seven symphonies he approached the basic

problems of form, tonality, and architecture in unique, individual

ways. On the one hand, his symphonic (and tonal) creativity was novel,

but others thought that music should be taking a different route.

Sibelius's response to criticism was dismissive: "Pay no attention to

what critics say. No statue has ever been put up to a critic." Sibelius

has fallen in and out of fashion, but remains one of the most popular

20th century symphonists, with complete cycles of his symphonies

continuing to be recorded. In his own time, however, he focused far

more on the more profitable chamber music for home use, and

occasionally on works for the stage. Eugene Ormandy and, to a lesser extent, his predecessor Leopold Stokowski, were instrumental in bringing Sibelius's music to American audiences by

programming his works often, and the former thereby developed a

friendly relationship with Sibelius throughout his life. In 1990, the composer Thea Musgrave was commissioned by the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra to write a piece in honour of the 125th anniversary of Sibelius's birth. Song of the Enchanter was premiered on 14 February 1991. Research by T.L. Jackson of the University of North Texas, in which he investigated the composer's connections to Nazi Germany, led him to conclude that the composer actively supported, and benefited

from, National Socialism. Other scholars have said such conclusions,

which fail to account for the exclusively German origin of their source

material, are simplistic.

“ I

said that I admired [the symphony's] severity of style and the profound

logic that created an inner connection between all the motifs...

Mahler's opinion was just the reverse. 'No, a symphony must be like the

world. It must embrace everything.' ” “ If Sibelius is good, this invalidates the standards of musical quality that have persisted from Bach to Schoenberg: the richness of inter-connectedness, articulation, unity in diversity, the 'multi-faceted' in 'the one'. ”