<Back to Index>

- Astronomer Tyge (Tycho) Ottesen Brahe, 1546

- Poet Paul Éluard, 1895

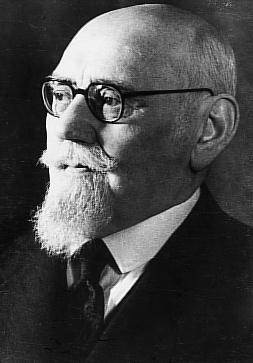

- President of Austria Karl Renner, 1870

PAGE SPONSOR

Karl Renner (14 December 1870 – 31 December 1950) was an Austrian politician. He was born in Untertannowitz (Dolní Dunajovice, Moravia) and died in Vienna. He is called the Father of the Republic because he headed the first government in republican Austria in 1918 and was once again decisive in establishing the present Second Republic in 1945, becoming its first President.

Renner was born the 18th child of a small farmer but, because of his intelligence, was allowed to attend a selective gymnasium. One of his teachers was Wilhelm Jerusalem. From 1890 to 1896 he studied law at the University of Vienna. In 1895 he was one of the founding members of the Naturfreunde (Friends of Nature) organisation and created their logo. Being interested in politics he became a librarian in parliament. During these early years he already opened up new perspectives in anlysis both of national conflict and of private law - all the while disowning his innovative ideas under a variety of pseudonyms lest he lose his coveted post as parliamentary librarian.

When in 1918, after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, he became the first head of government ("State Chancellor") of that newly established small German speaking republic which did not wish to be considered the heir of the Habsburg monarchy. He thus suggested the novel name "Norische Republik", or Noric Republic, for an altogether new state, a reference to the ancient Celtic "regnum Noricum", a kingdom that covered almost the same area as the new state and was later incorporated as a province in the Roman Empire. His suggestion was passed over in favour of "Republik Deutsch-Österreich," i.e. Republic of German-Austria, a name that in the Treaty of Saint-Germain of 1919 was prohibited by The Entente when they crushed the resolution of the Constituent National Assembly in Vienna that "German-Austria" was to be part of the German Republic. Even before the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy Renner had proposed a future union of the German parts of Austria with, even using the word "Anschluss".

Renner was always interested in politics and in 1896 he joined the Social Democratic Party of Austria (SPÖ), representing the party in the Reichsrat from 1907 till its dissolution in November 1918. He was in the forefront of the Provisional and the Constitutional National Assemblies of those "Lands Represented in the Reichsrat" (the formal description of the Austrian half of the Dual Monarchy) that predominantly spoke German and had decided to form a nation state just like all the other nationalities had done. He was the leader of the delegation that represented this new German-Austria in the negotiations of St. Germain where the "Republic of Austria" was acknowledged but was declared to be the responsible successor to Imperial Austria. There Renner had to accept that this new Austria was prohibited any political association with Germany and he had to accept the loss of the German speaking South Tyrol and the German speaking parts of Bohemia and Moravia where he himself was born; this forced him to give up his share in the parental farm if he, "the peasant proprietor who turned Marxist", wanted to remain an Austrian government officer.

Renner was Chancellor of Austria of

the first three coalition cabinets and Minister of Foreign Affairs from

1918 until 1920, and, from 1931 to 1933, he was President of

Parliament, the National Council of Austria. In the time of authoritarian Austrofascism from 1934, when his party was prohibited, he even welcomed the Anschluss. Having originally been a proponent of new German-Austria becoming a part of the democratic German Republic, he expected Nazism to be but a passing phenomenon not worse than the dictatorship of Dollfuß and Schuschniggs's authoritarian one-party systemm, which had ruled Austria. During World War II, however, he distanced himself from politics completely. In April 1945, just before the collapse of the Third Reich, the defeat of Germany and the end of the war, Renner set up a Provisional Government in Vienna with other politicians from the three revived parties SPÖ (social-democrat), ÖVP (conservative, successor to the Christian Social Party) and KPÖ (communist).

On April 27, by a declaration, this Provisional Government separated

Austria from Germany and campaigned for the country to be acknowledged

as an independent republic. As a result of Renner's actions Austria was

to benefit greatly in the eyes of the Allies as she had fulfilled the

stipulation of the Moscow Declaration of

1943, where the Foreign Secretaries of US, UK and USSR declared that

the annexation (Anschluss) of Austria by Germany was null and void

calling for the establishment of a free Austria after the victory over

Nazi Germany provided that Austria could demonstrate that she had

undertaken suitable actions of her own in that direction. Thus Austria,

having been invaded by Germany, was treated as an unwilling party and

"the first victim" of Nazi Germany. Being suspicious of the fact that the Russians in Vienna were the first to accept Renner's Cabinet, the Western Allies hesitated

half a year with their recognition, but his Provisional Government was

in the end recognised by all Four Powers on Oct. 20 and Renner was thus the first post-war Chancellor. In late 1945, he was elected the first President of the Second Republic. Karl Renner died in 1950 and was buried in the Presidential Tomb at Zentralfriedhof in Vienna.

For most of his life, Renner alternated between the political commitment of a Social Democrat and

the analytical distance of an academic scholar. Central to Renner's

academic work is the problem of the relationship between law and social

transformations. With his Rechtsinstitute des Privatrechts und ihre soziale Funktion. Ein Beitrag zur Kritik des bürgerlichen Rechts (1904), he became one of the founders of the discipline of the sociology of law. His and Otto Bauer's ideas about the legal protection of cultural minorities were taken up by the Jewish Bund, but fiercely denounced by Lenin. Stalin devoted a whole chapter to criticising Cultural National Autonomy in Marxism and the National Question.