<Back to Index>

- Physicist Joseph John "J.J." Thomson, 1856

- Painter Willem van de Velde the Younger, 1633

- Chancellor of Germany Willy Brandt, 1913

PAGE SPONSOR

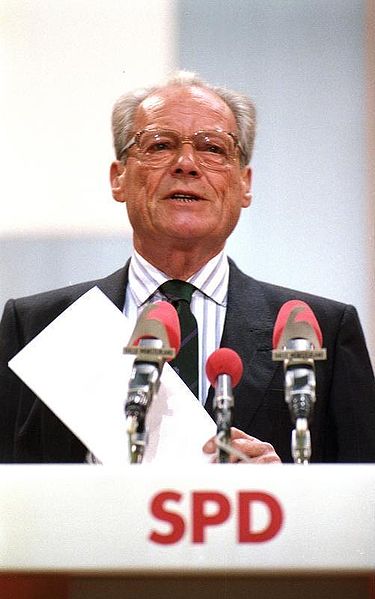

Willy Brandt, born Herbert Ernst Karl Frahm (18 December 1913 - 8 October 1992), was a German politician, Chancellor of West Germany 1969 – 1974, and leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) 1964 – 1987.

Brandt's most important legacy was Ostpolitik, a policy aimed at improving relations with East Germany, Poland, and the Soviet Union. This policy caused considerable controversy in West Germany, but won Brandt the Nobel Peace Prize in 1971. In 1974, Brandt resigned as Chancellor after Günter Guillaume, one of his closest aides, was exposed as an agent of the Stasi, the East German secret police. Willy Brandt was born Herbert Ernst Karl Frahm in Lübeck, Germany, to

Martha Frahm, an unwed mother who worked as a cashier for a department

store. His father was an accountant from Hamburg named John

Möller, whom Brandt never met. As his mother worked six days a

week, he was mainly brought up by his mother's stepfather Ludwig Frahm

and his second wife Dora. After passing his Abitur in 1932 at Johanneum zu Lübeck, he became an apprentice at the shipbroker and ship's agent F.H. Bertling. He joined the "Socialist Youth" in 1929 and the Social Democratic Party (SPD) in 1930. He left the SPD to join the more left wing Socialist Workers Party (SAP), which was allied to the POUM in Spain and the Independent Labour Party in Britain. In 1933, using his connections with the port and its ships, he left Germany for Norway to escape Nazi persecution. It was at this time that he adopted the pseudonym Willy Brandt to avoid detection by Nazi agents. In 1934, he took part in the founding of the International Bureau of Revolutionary Youth Organizations, and was elected to its Secretariat. Brandt was in Germany from September to December 1936, disguised as a Norwegian student named Gunnar Gaasland. He was married to Gertrud Meyer from Lübeck in a fictitious marriage to protect her from deportation. Meyer had joined Brandt in Norway in July 1933. In 1937, during the Civil War, Brandt worked in Spain as a journalist. In 1938, the German government revoked his citizenship, so he applied for Norwegian citizenship.

In 1940, he was arrested in Norway by occupying German forces, but was

not identified as he wore a Norwegian uniform. On his release, he

escaped to neutral Sweden. In August 1940, he became a Norwegian citizen, receiving his passport from the Norwegian embassy in Stockholm, where he lived until the end of the war. Willy Brandt lectured in Sweden on 1 December 1940 at Bommersvik college about problems experienced by the social democrats in Nazi Germany and the occupied countries at the start of World War II. In exile in Norway and Sweden Brandt learned Norwegian and Swedish. Brandt spoke Norwegian fluently, and retained a close relationship with Norway. In late 1946, Brandt returned to Berlin, working for the Norwegian government. In 1948, he joined the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and became a German citizen again, formally adopting the pseudonym, Willy Brandt, as his legal name. From 3 October 1957, to 1966, Willy Brandt was Mayor of West Berlin, during a period of increasing tension in East-West relations that led to the construction of the Berlin Wall. In Brandt's first year as Mayor, he also served as the President of the Bundesrat in Bonn. Brandt was outspoken against the Soviet repression of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution and against Nikita Khrushchev's 1958 proposal that Berlin receive the status of a "free city". He was supported by the influential publisher Axel Springer. Brandt

became the Chairman of the SPD in 1964, a post that he retained until

1987, longer than any other party Chairman since its foundation by August Bebel. Brandt was the SPD candidate for the Chancellorship in 1961, but he lost to Konrad Adenauer's conservative Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU). In 1965, Brandt ran again, but lost to the popular Ludwig Erhard. Erhard's government was short-lived, however, and in 1966 a grand coalition between the SPD and CDU was formed, with Brandt as Foreign Minister and Vice-Chancellor.

At

the 1969 elections, again with Brandt as the leading candidate, the SPD

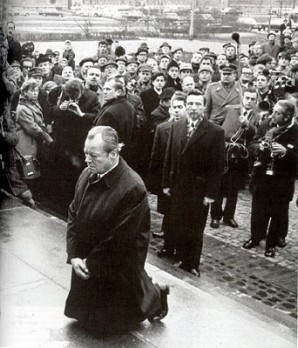

became stronger, and after three weeks of negotiations, the SPD formed a coalition government with the smaller Free Democratic Party of Germany (FDP). Brandt was elected Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany. As Chancellor, Brandt developed his Neue Ostpolitik. Brandt was active in creating a degree of rapprochement with East Germany, and also in improving relations with the Soviet Union, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and other Eastern Bloc (communist) countries. A seminal moment came in December 1970 with the famous Warschauer Kniefall in which Brandt, apparently spontaneously, knelt down at the monument to victims of Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

The uprising occurred during the Nazi German military occupation of

Poland, and the monument is to those killed by the German troops who

suppressed the uprising and deported remaining ghetto residents to the

concentration camps for extermination. Time magazine in the U.S.A. named Brandt as its Man of the Year for

1970, stating, "Willy Brandt is in effect seeking to end World War II

by bringing about a fresh relationship between East and West. He is

trying to accept the real situation in Europe, which has lasted for 25

years, but he is also trying to bring about a new reality in his bold

approach to the Soviet Union and the East Bloc." In 1971, Brandt received the Nobel Peace Prize for his work in improving relations with East Germany, Poland, and the Soviet Union. Brandt

negotiated a peace treaty between the Federal Republic of Germany and

Poland, and agreements on the boundaries between the two countries,

signifying the official and long-delayed end of World War II. Brandt negotiated parallel treaties and agreements between the Federal Republic and Czechoslovakia. In West Germany, Brandt's Neue Ostpolitik was

extremely controversial, dividing the populace into two camps: one

camp, embracing all of the conservative parties and most notably the

victims i.e. those German-speaking, West German residents and their

subsequent families who were driven west ("die Heimatvertriebene") by Stalinist ethnic cleansing from Historical Eastern Germany, especially the part that was arbitrarily given to Poland by the Stalinists; western Czechoslovakia (the Sudetenland); and the rest of Eastern Europe, such as in Romania.

These groups of displaced Germans and their descendants loudly voiced

their opposition to Brandt's policy, calling it "illegal" and "high

treason". A different camp supported and encouraged Brandt's Neue Ostpolitik as aiming at "Wandel durch Annäherung" ("change through rapprochement"),

encouraging change through a policy of engagement with the (communist)

Eastern Bloc, rather than trying to isolate those countries

diplomatically and commercially. Brandt's supporters claim that the

policy did help to break down the Eastern Bloc's "siege mentality",

and also helped to increase its awareness of the contradictions in its

brand of Socialism Communism, which – together with other events –

eventually led to downfall of Eastern European Communism and Stalinism.

West Germany in the late 1960s was shaken by student disturbances and

a general "change of the times" that not all Germans were willing to

accept or approve. What had seemed a stable, peaceful nation, happy

with its outcome of the "Wirtschaftswunder" ("economic miracle") faced

economic turbulence. The German baby-boom generation wanted to come to

terms with the deeply conservative, bourgeois, and demanding parent

generation. The baby-boomer students were the most outspoken, and they

accused their "parental generation" of its Nazi past. Even worse, they

accused it of being outdated and old-fashioned. Compared to their

forebears, the "skeptical generation" was much more capricious, willing

to embrace more extreme socialist ideology (such as Maoism), and public

heroes (such as Ho Chi Minh, Fidel Castro, and Che Guevara),

while living a looser and more promiscuous lifestyle. Students and

young apprenticees could afford to move out of their parents' homes,

and left-wing politics was considered to be chic, as well as taking part in American style political demonstrations against having American military forces in South Vietnam.

Brandt's predecessor as Chancellor, Kurt Georg Kiesinger,

had been a member of the Nazi party, and was an old-fashioned German

bourgeois and conservative intellectual. Brandt, having fought the

Nazis and having faced down communist Eastern Germany during several

crises while he was the Mayor of Berlin, became a controversial, but

credible, figure in several different factions. As the Minister of

Foreign Affairs in Kiesinger's grand coalition cabinet,

Brandt helped to gain further international approval for Western

Germany, and he laid the foundation stones for his future Neue Ostpolitik. There was a wide public-opinion gap between Kiesinger and Brandt in the West German polls. Both

men had come to their own terms with the new baby boomer lifestyles.

Kiesinger considered them to be "a shameful crowd of long-haired

drop-outs who needed a bath and someone to discipline them". On the

other hand, Brandt needed a while to get into contact with, and to earn

credibility among, the "Ausserparlamentarische Opposition"

(APO) ("the extra-parlimentary opposition"). The students questioned

West German society in general, seeking social, legal, and political

reforms. Also, the unrest led to a renaissance of right-wing parties in

some of the Bundeslands' (German states under the Bundesrepublik) Parliaments.

Brandt,

however, represented a figure of change, and he followed a course of

social, legal, and political reforms. In 1969, Brandt gained a small

majority by forming a coalition with the FDP. In his first speech

before the Bundestag as the Chancellor, Brandt set forth his political

course of reforms ending the speech with his famous words, "Wir wollen

mehr Demokratie wagen" (literally: "We want to take a chance on more

Democracy", or more figuratively, "Let's dare more democracy"). This

speech made Brandt, as well as the Social Democratic Party, popular

among most of the students and other young West German baby-boomers who

dreamed of a country that would be more open and more colorful than the

frugal and still somewhat authoritarian Bundesrepublik that had been

built after World War II. However, Brandt's Neue Ostpolitik lost for him a large part of the German refugee (from the East) voters who had been significantly pro-SPD in the postwar years. Although

Brandt is perhaps best known for his achievements in foreign policy,

his government oversaw the implementation of a broad range of social

reforms, and according to Giles and Lisanne Radice in “Socialists in

the Recession,” he was known as a Kanzler der inneren Reformen

(Chancellor of domestic reform). Amongst his achievements as chancellor

include: Though

Brandt remained Chancellor, he had lost his majority. Subsequent

initiatives in parliament, most notably on the budget, failed. Because

of this stalemate, the Bundestag was dissolved and new elections were

called. During the 1972 campaign, many popular West German artists,

intellectuals, writers, actors and professors supported Brandt and the

SPD. Among them were Günter Grass, Walter Jens, and even the soccer player Paul Breitner.

Brandt's Ostpolitik as well as his reformist domestic policies were

popular with parts of the young generation and led his SPD party to its

best-ever federal election result in late 1972. The "Willy-Wahl",

Brandts landslide win was the beginning of the end; and Brandts role in

government started to decline. Many

of Brandt's reforms met with resistance from state governments

(dominated by CDU/CSU). The spirit of reformist optimism was cut short

by the 1973 oil crisis and the major public services strike 1974, which gave Germany's trade unions, led by Heinz Kluncker,

a big wage increase but reduced Brandt's financial leeway for further

reforms. Brandt was said to be more a dreamer than a manager and was

personally haunted by depression. To counter any notions about being

sympathetic to Communism or soft on left-wing extremists, Brandt

implemented tough legislation that barred "radicals" from public

service ("Radikalenerlass"). Around 1973, West German security organizations received information that one of Brandt's personal assistants, Günter Guillaume,

was a spy for the East German intelligence services. Brandt was asked

to continue working as usual, and he agreed to do so, even taking a

private vacation with Guillaume. Guillaume was arrested on April 24,

1974, and many blamed Brandt for having a communist spy in his

inner circle. Thus disgraced, Brandt resigned from his position as the

Chancellor on May 6, 1974. However, Brandt remained in the Bundestag and as the Chairman of the Social Democrats through 1987. This espionage affair

is widely considered to have been just the trigger for Brandt's

resignation, not the fundamental cause. Brandt was dogged by scandals

about serial adultery, and reportedly also struggled with alcohol and

depression. There was also the economic fallout on West Germany of the 1973 oil crisis,

which almost seems to have been enough stress to finish off Brandt as

the Chancellor. As Brandt himself later said, "I was exhausted, for

reasons which had nothing to do with the process going on at the time." (Where

"the process" seems to have been the unfolding of the Guillaume

espionage scandal.) Guillaume had been an espionage agent for East Germany, who was supervised by Markus Wolf,

the head of the "Main Intelligence Administration" of the East German

Ministry for State Security. Herr Wolf has stated after the

reunification that the resignation of Brandt had never been intended,

and that the planting and handling of Guillaume had been one of the

largest mistakes of the East German secret services. Brandt was succeeded as the Chancellor of the Bundesrepublik by his fellow Social Democrat, Helmut Schmidt. For the rest of his life, Brandt remained suspicious that his fellow Social Democrat (and longtime rival) Herbert Wehner had been scheming for Brandt's downfall. However, evidence for this suspicion is scant.

After his term as the Chancellor, Brandt retained his seat in the Bundestag,

and he remained the Chairman of the Social Democratic Party through

1987. Beginning in 1987, Brandt stepped down to become the Honorary

Chairman of the party. Brandt was also a member of the European Parliament from 1979 to 1983. For sixteen years, Brandt was the president of the Socialist International (1976

– 92), during which period the number of Socialist International's

mainly European member parties grew until there were more than a

hundred socialist, social democratic, and labour political parties

around the world. For the first seven years, this growth in SI

membership had been prompted by the efforts of the Socialist

International's Secretary-General, the Swede Bernt Carlsson.

However, in early 1983, a dispute arose about what Carlsson perceived

as the SI president's authoritarian approach. Carlsson then rebuked

Brandt saying: "this is a Socialist International — not a German

International". Next, against some vocal opposition, Brandt decided to move the next Socialist International Congress from Sydney, Australia, to Portugal.

Following this SI Congress in April 1983, Brandt retaliated against

Carlsson by forcing him to step down from his position. However, the Austrian Prime Minister, Bruno Kreisky, argued on behalf of Brandt: "It is a question of whether it is better to be pure or to have greater numbers".

In

1977, Brandt was appointed as the chairman of the Independent

Commission for International Developmental Issues. This produced a

report in 1980, which called for drastic changes in the global attitude

towards development in the Third World. This became known as the Brandt Report.

In October 1979, Brandt met with the East German dissident, Rudolf Bahro, who had written The Alternative. Bahro and his supporters were attacked by the East German state security organization Stasi, headed by Erich Mielke,

for his writings, which had laid the theoretical foundation of a

leftist opposition to the ruling SED party and its dependent allies,

and which promoted new and changed parties. All of this is now

described as "change from within". Brandt had asked for Bahro's

release, and Brandt welcomed Bahro's theories, which advanced the

debate within his own Social Democratic Party. In late 1989, Brandt

became one of the first leftist leaders in West Germany to publicly

favor a quick reunification of

Germany, instead of some sort of two-state federation or other kind of

interim arrangement. Brandt's public statement "Now grows together what

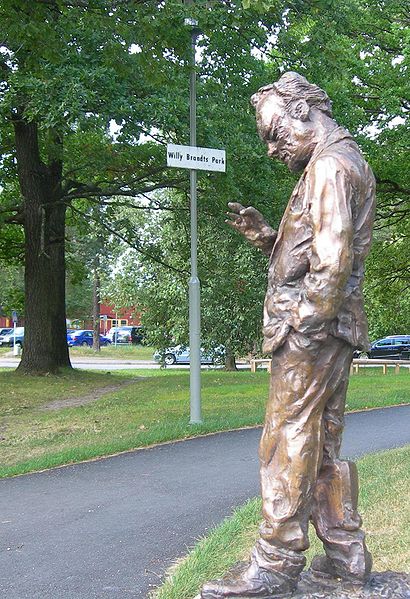

belongs together," was widely quoted in those days. One of Brandt's last public appearances was in flying to Baghdad, Iraq, to free Western hostages held by Saddam Hussein, following the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990. Brandt secured the release of a large number of them, and on November 9, 1990, his airplane landed with 174 freed hostages on board at the Frankfurt Airport. Willy Brandt died of colon cancer at his home in Unkel, a town on the Rhine River, on October 8, 1992, and was given a state funeral. He was buried at the cemetery at Zehlendorf in Berlin. When

the SPD moved its headquarters from Bonn back to Berlin in the

mid-1990s, the new headquarters was named the "Willy Brandt Haus". One

of the buildings of the European Parliament in Brussels was named after him in 2008. A private German-language secondary school in Warsaw, Poland, is named after Brandt. On 11 December 2009, Willy Brandt's name was attached to Berlin-Brandenburg International Airport.

Brandt's Ostpolitik led to a meltdown of the narrow majority Brandt's coalition enjoyed in the Bundestag. In October 1970, FDP deputies Erich Mende, Heinz Starke, and Siegfried Zoglmann crossed the floor to join the CDU. On 23 February 1972, SPD deputy Herbert Hupka, who was also leader of the Bund der Vertriebenen,

joined the CDU in disagreement with Brandt's reconciliatory efforts

towards the east. On 23 April 1972, Wilhelm Helms (FDP) left the

coalition ; the FDP politicians Knud von Kühlmann-Stumm and

Gerhard Kienbaum also declared that they would vote against Brandt;

thus, Brandt had lost his majority. On 24 April 1972 a vote of no

confidence was proposed and it was voted on three days later. Had this

motion passed, Rainer Barzel would

have replaced Brandt as Chancellor. To everyone's surprise, the motion

failed: Barzel got only 247 votes out of 260 ballots; for an absolute

majority, 249 votes would have been necessary. There were also 10 votes

against the motion and 3 invalid ballots. It was not revealed until

much later that two Bundestag members (Julius Steiner and Leo Wagner, both of the CDU/CSU) had been bribed by the East German Stasi to vote for Brandt.