<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Srīnivāsa Aiyangār Rāmānujan, 1887

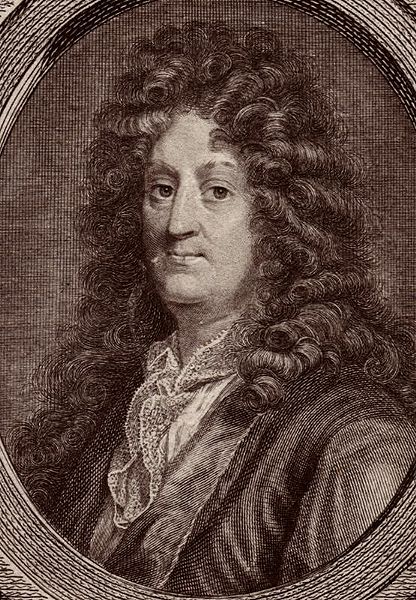

- Dramatist Jean Racine, 1639

- Founder and Governor of Georgia James Edward Oglethorpe, 1696

PAGE SPONSOR

Jean Racine (December 22, 1639 – April 21, 1699) was a French dramatist, one of the "Big Three" of 17th century France (along with Molière and Corneille), and one of the most important literary figures in the Western tradition. Racine was primarily a tragedian, though he did write one comedy.

Racine was born on 22 December 1639 in La Ferté-Milon (Aisne), in the former Picardy province in northern France. He was an orphan by the age of four (his mother died in 1641 and his father in 1643) and was raised by his grandparents. At the death of his grandfather, in 1649, his grandmother, Marie des Moulins, went to live in the convent of Port-Royal and took her grandson with her. He received a classical education at the Petites écoles de Port-Royal, a religious institution which would greatly influence other contemporary figures including Blaise Pascal. Port-Royal was run by followers of Jansenism, a theology condemned as heretical by the French bishops and the Pope. Racine's interactions with the Jansenists in his years at this academy would have great influence over him for the rest of his life. At Port-Royal, he excelled in his studies of the Classics and the themes of Greek and Roman mythology would play large roles in his future works. He was expected to study law at the Collège de Harcourt in Paris but, instead, found himself drawn to a more artistic lifestyle. Experimenting with poetry yielded high praise from France's greatest literary critic, Nicolas Boileau with whom Racine would later become great friends, and Boileau would often claim that he was behind the budding poet's work. He eventually took up residence in Paris where he became involved in theatrical circles.

His first play, Amasie, never reached the stage. On 20 June 1664, Racine's tragedy La Thébaïde ou les frères ennemis (The Thebans or the enemy Brothers) was produced by Molière's troupe at the Théâtre du Palais-Royal, in Paris. The following year, Molière also put on Racine's second play, Alexandre Le Grand. However, this play garnered such good feedback from the public that Racine secretly negotiated with a rival play company, the Hôtel de Bourgogne, to perform the play since they had a better reputation for performing tragedies. Thus, Alexandre premiered for the second time, by a different acting troupe, eleven days after its first showing. Molière could never forgive Racine for his betrayal, and Racine simply widened the rift between him and his former friend by seducing Molière's leading actress, Thérèse du Parc, into becoming his companion both professionally and personally. From this point on, all of Racine's secular plays were performed by the Hôtel de Bourgogne troupe.

Though both La Thébaide (1664) and its successor, Alexandre (1665), had classical themes, Racine was already entering into controversy and forced to field accusations that he was polluting the minds of his audiences. He broke all ties with Port-Royal, and proceeded with Andromaque (1667), which told the story of Andromache, widow of Hector, and her fate following the Trojan War. He was by now acquiring many rivals, including Pierre Corneille and his brother, Thomas Corneille. Tragedians often competed with alternative versions of the same plot: for example, Michel le Clerc produced an Iphigénie in the same year as Racine (1674), and Jacques Pradon also wrote a play about Phèdre (1677). The success of Pradon's work (the result of the activities of a claque) was one of the events which caused Racine to renounce his work as a dramatist at that time, even though his career up to this point was so successful that he was the first French author to live almost entirely on the money he earned from his writings. Others, including the historian W.H. Lewis, attribute his retirement from the theater to qualms of conscience.

However, one major incident which seems to have contributed to Racine's departure from public life was his implication in a court scandal of 1679. He got married at about this time to the pious Catherine de Romanet, and his religious beliefs and devotion to the Jansenist sect were revived. He and his wife eventually had two sons and five daughters. Around the time of his marriage and departure from the theater, Racine accepted a position as a royal historiographer in the court of King Louis XIV, alongside his friend Boileau. He kept this position in spite of the minor scandals he was involved in. In 1672, he was elected to the Académie française, eventually gaining much power over this organization. Two years later, he was bestowed the title of "treasurer of France", and he was later distinguished as an "ordinary gentleman of the king" (1690), and then as a secretary of the king (1696). Because of his flourishing career in the court, Louis XIV provided for his widow and children after his death. When at last he returned to the theatre, it was at the request of Madame de Maintenon, morganatic second wife of King Louis XIV, with the moral fables, Esther (1689) and Athalie (1691), both of which were based on Old Testament stories and intended for performance by the pupils of the school of the Maison royale de Saint-Louis in Saint-Cyr, (a commune neighboring Versailles, and now known as "Saint-Cyr l'École".)

Jean Racine died in 1699 from cancer of the liver. He requested to be buried in Port-Royal, but after Louis XIV had this site razed in 1710, his remains were moved to the Saint-Étienne-du-Mont church in Paris.

Tragedy shows how men fall from prosperity to disaster. The higher the position from which the hero falls, the greater, in a sense, is the tragedy; and not until Henrik Ibsen's time do we really get away from the convention of royal or otherwise illustrious protagonists. Except for the confidants, amongst whom only Narcisse and Œnone are of any importance, Racine describes the fate of kings, queens, princes and princesses, liberated from the constricting pressures of everyday life and able to speak and act without inhibition.

Greek

tragedy, from which Racine borrowed so plentifully, tended to assume

that humanity was under the control of gods indifferent to its

sufferings and aspirations. In the Œdipus Tyrannus Sophocles's

hero becomes gradually aware of the terrible fact that, however hard

his family have tried to avert the oracular prophecy, he has

nevertheless killed his father and married his mother and must now pay

the penalty for these unwitting crimes. The same awareness of a cruel

fate, that leads innocent men and women into sin and demands

retribution of the equally innocent children, pervades La Thébaïde, a play which itself deals with the legend of Œdipus. A Jansenist by birth and education, Racine was deeply influenced by its sense of fatalism. But, being a Christian, he can no longer assume, as did Æschylus and Sophocles,

that God is merciless in leading men to a doom which they do not

foresee. Instead, destiny becomes (at least, in the secular plays) the

uncontrollable frenzy of unrequited love. As already in the works of Euripides, the gods have become symbolic. Venus represents

the unquenchable force of sexual passion within the human being; but

closely allied to this – indeed, indistinguishable from it – is the

atavistic strain of monstrous aberration that had caused her mother Pasiphaë to mate with a bull and give birth to the Minotaur. Thus, in Racine the hamartía, which the thirteenth chapter of Aristotle’s Poetics had

declared a characteristic of tragedy, is not merely an action performed

in all good faith which subsequently has the direst consequences

(Œdipus's killing a stranger on the road to Thebes, and marrying the

widowed Queen of Thebes after solving the Sphinx's riddle), nor is it simply an error of judgment (as when Deianira, in the Hercules Furens of Seneca the Younger, kills her husband when intending to win back his love); it is a flaw of character. In

a second important respect Racine is at variance with the Greek pattern

of tragedy. His tragic characters are aware of, but can do nothing to

overcome, the blemish which leads them on to a catastrophe. And the

tragic recognition, or anagnorisis, of wrongdoing is not confined, as in the Œdipus Tyrannus,

to the end of the play, when the fulfilment of the prophecy is borne in

upon Œdipus; Phèdre realizes from the very beginning the

monstrousness of her passion, and preserves throughout the play a

lucidity of mind that enables her to analyse and reflect upon this

fatal and hereditary weakness. Hermione's situation is rather closer to

that of Greek tragedy. Her love for Pyrrhus is perfectly natural and is

not in itself a flaw of character. But despite her extraordinary

lucidity in analysing her violently fluctuating states of

mind, she is blind to the fact that the King does not really love her,

and this weakness on her part, which leads directly to the

tragic peripeteia, is the hamartía from which the tragic outcome arises. For

Racine love closely resembles a physiological disorder. It is a fatal

illness with alternating moods of calm and crisis, and with deceptive

hopes of recovery or fulfilment (Andromaque; Phèdre),

the final remission culminating in a quick death. His

main characters are monsters, and stand out in glaring contrast to the

regularity of the plays' structure and versification. The suffering

lover Hermione, Roxane or Phèdre is aware of nothing except her

suffering and the means whereby it can be relieved. Her love is not

founded upon esteem of the beloved and a concern for his happiness and

welfare, but is essentially selfish. In a torment of jealousy she tries

to relieve the “pangs of despised love” by having (or, in

Phèdre's case, allowing) him to be put to death, and thus

associating him with her own suffering. The depth of tragedy is reached

when Hermione realizes that Pyrrhus's love for Andromaque continues

beyond the grave, or when Phèdre contrasts the young lovers'

purity with her unnaturalness which should be hidden from the light of

day. Racine's most distinctive contribution to literature is his

conception of the ambivalence of love: “ne puis-je savoir si j'aime, ou

si je hais?” The

passion of these lovers is totally destructive of their dignity as

human beings, and usually kills them or deprives them of their reason.

Except for Titus and Bérénice, they are blinded by it to

all sense of duty. Pyrrhus casts off his fiancée in order to

marry a slave from an enemy country, for whom he is prepared to

repudiate his alliances with the Greeks. Oreste's duties as an

ambassador are subordinate to his aspirations as a lover, and he

finally murders the king to whom he has been sent. Néron's

passion for Junie causes him to poison Britannicus and thus, after

three years of virtuous government, to inaugurate a tyranny. The

characteristic Racinian framework is that of the eternal triangle, two

young lovers, a prince and a princess, being thwarted in their love by

a third person, usually a queen whose love for the young prince is

unreciprocated. Phèdre destroys the possibility of a marriage

between Hippolyte and Aricie. Bajazet and Atalide are prevented from

marrying by the jealousy of Roxane. Néron divides Britannicus

from Junie. In Bérénice the amorous couple are kept apart by considerations of state. In Andromaque the

system of unrequited passions borrowed from tragicomedy alters the

dramatic scheme, and Hermione destroys a man who has been her

fiancé, but who has remained indifferent to her, and is now

marrying a woman who does not love him. The young princes and princesses are agreeable, display varying degrees of innocence and

optimism and are the victims of evil machinations and the love/hatred

characteristic of Racine. The

king (Pyrrhus, Néron, Titus, Mithridate, Agamemnon,

Thésée) holds the power of life and death over the other

characters. Pyrrhus forces Andromaque to choose between marrying him

and seeing her son killed. After keeping his fiancée waiting in Epirus for

a year he announces his intention of marrying her, only to change his

mind almost immediately afterwards. Mithridate discovers Pharnace's

love for Monime by spreading a false rumour of his own death. By

pretending to renounce his fiancée he finds that she had

formerly loved his other son Xipharès. Wrongly informed that

Xipharès has been killed fighting Pharnace and the Romans, he

orders Monime to take poison. Dying, he unites the two lovers.

Thésée is a rather nebulous character, primarily

important in his influence upon the mechanism of the plot.

Phèdre declares her love to Hippolyte on hearing the false news

of his death. His unexpected return throws her into confusion and lends

substance to Œnone's allegations. In his all too human blindness he

condemns to death his own son on a charge of which he is innocent. Only

Amurat does not actually appear on stage, and yet his presence is

constantly felt. His intervention by means of the letter condemning

Bajazet to death precipitates the catastrophe. The

queen shows greater variations from play to play than anyone else, and

is always the most carefully delineated character. Hermione (for she,

rather than the pathetic and emotionally stable Andromaque, has a

rôle equivalent to that generally played by the queen) is young,

with all the freshness of a first and only love; she is ruthless in

using Oreste as her instrument of vengeance; and she is so cruel in her

brief moment of triumph that she refuses to intercede for Astyanax's

life. Agrippine, an ageing and forlorn woman, “fille, femme, sœur et

mère de vos maîtres”, who has stopped at nothing in order

to put her own son on the throne, vainly tries to reassert her

influence over Néron by espousing the cause of a prince whom she

had excluded from the succession. Roxane, the fiercest and bravest in

Racine's gallery of queens, has no compunction in ordering Bajazet's

death and indeed banishes him from her presence even before he has

finished justifying himself. Clytemnestre is gentle and kind, but quite

ineffectual in rescuing her daughter Iphigénie from the threat

of sacrifice. Phèdre, passive and irresolute, allows herself to

be led by Œnone; deeply conscious of the impurity of her love, she sees

it as an atavistic trait and a punishment of the gods; and she is so

consumed by jealousy that she can do nothing to save her beloved from

the curse. The

confidants' primary function is to obviate the need for monologues.

Only very rarely do they further the action. They invariably reflect

the character of their masters and mistresses. Thus, Narcisse and

Burrhus symbolize the warring elements of evil and good within the

youthful Néron. But Narcisse is more than a reflection: he

betrays and finally poisons his master Britannicus. Burrhus, on the

other hand, is the conventional “good angel” of the medieval morality play.

He is a much less colourful character than his opposite number. Œnone,

Phèdre's evil genius, persuades her mistress to tell Hippolyte

of her incestuous passion, and incriminates the young prince on

Thésée's unexpected return. Céphise, knowing how

deeply attached Pyrrhus is to her mistress, urges the despairing

Andromaque to make a last appeal to him on her son's behalf, and so

changes the course of the play. Unlike such plays as Hamlet and The Tempest,

in which a dramatic first scene precedes the exposition, a Racinian

tragedy opens very quietly, but even so in a mood of suspense. In Andromaque Pyrrhus's

unenviable wavering between Hermione and the eponymous heroine has been

going on for a year and has exasperated all three. Up to the time when Britannicus begins,

Néron has been a good ruler, a faithful disciple of Seneca and

Burrhus, and a dutiful son; but he is now beginning to show a spirit of

independence. With the introduction of a new element (Oreste's demand

that Astyanax should be handed over to the Greeks, Junie's abduction,

Abner's unconscious disclosure that the time to proclaim Joas has

finally come), an already tense situation becomes, or has become,

critical. In a darkening atmosphere a succession of fluctuating states

of mind on the part of the main characters brings us to the resolution

– generally in the fourth Act, but not always (Bajazet, Athalie)

– of what by now is an unbearable discordance. Hermione entrusts the

killing of Pyrrhus to Oreste; wavers for a moment when the King comes

into her presence; then, condemns him with her own mouth. No sooner has

Burrhus regained his old ascendancy over Néron, and reconciled

him with his half-brother, than Narcisse most skilfully overcomes the

emperor's scruples of conscience and sets him on a career of vice of

which Britannicus's murder is merely the prelude. By the beginning of

Act IV of Phèdre Œnone

has besmirched Hippolyte's character, and the Queen does nothing during

that Act to exculpate him. With the working-out of a situation usually

decided by the end of Act IV, the tragedies move to a swift conclusion.