<Back to Index>

- Egyptologist Jean François Champollion, 1790

- Writer Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, 1896

- Emperor and Autocrat of All the Russias Alexander I, 1777

PAGE SPONSOR

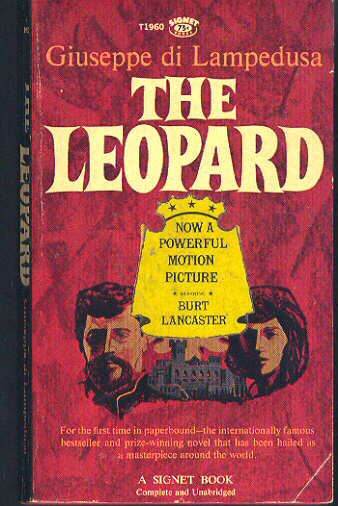

Giuseppe Tomasi, 11th Prince of Lampedusa (December 23, 1896 - July 23, 1957), was a Sicilian writer. He is most famous for his only novel, Il Gattopardo (first published posthumously in 1958, translated as The Leopard) which is set in Sicily during the Risorgimento. A taciturn and solitary man, he passed a great deal of his time reading and meditating, and used to say of himself, "I was a boy who liked solitude, who preferred the company of things to that of people."

Tomasi was born in Palermo to Giulio Maria Tomasi, Prince of Lampedusa and Duke of Palma di Montechiaro, and Beatrice Mastrogiovanni Tasca di Cutò. He became an only child after the death (from diphtheria) of his sister. He was very close to his mother, a strong personality who influenced him a great deal, especially because his father was rather cold and detached. As a child he studied in their grand house in Palermo with a tutor (including the subjects of literature and English), with his mother (who taught him French) and with a grandmother who read him the novels of Emilio Salgari. In the little theater of the house in Santa Margherita di Belice, where he spent long vacations, he first saw a performance of Hamlet, performed by a company of travelling players. His cousin was Fulco di Verdura.

Beginning in 1911, he attended the liceo classico in Rome and later in Palermo; he moved definitively to Rome in 1915 and enrolled in the faculty of Jurisprudence; however, that year he was drafted into the army, fought in the lost battle of Caporetto, and was taken prisoner by the Austro-Hungarian Army. He was held in a POW camp in Hungary, but succeeded in escaping and returning to Italy. After being mustered out of the army as a Lieutenant, he returned to Sicily, alternately resting there and travelling with his mother, and continuing his studies of foreign literature. It was during this time that he first drafted in his mind the ideas for his future novel The Leopard. Originally his plan was to have the entire novel occur over the course of one day, similar to the famous modernist novel by James Joyce, Ulysses.

In Riga, Latvia, in 1932, he married Alexandra Wolff von Stomersee, nicknamed "Licy", a Baltic German noblewoman and student of psychoanalysis. The marriage ceremony was celebrated in an Orthodox Church. They first lived with di Lampedusa's mother in Palermo, but soon the incompatibility between the two women drove Licy back to Latvia.

In 1934 his father died and he inherited his princely title. He was briefly called back to arms in 1940, but, as head of a hereditary agricultural plantation, was soon sent back home to take care of its affairs. He and his mother ultimately took refuge in Capo d'Orlando, where he was reunited with Licy; they survived the war, but their palace in Palermo did not.

After

his mother died in 1946, Di Lampedusa returned to live with his wife in

Palermo. In 1953 he began to spend time with a group of young

intellectuals, one of whom was Gioacchino Lanza Tomasi, a cousin, with whom he developed such a close relationship that, the following year, he legally adopted him. Tomasi di Lampedusa was often the guest of his cousin, the poet Lucio Piccolo, with whom he travelled in 1954 to San Pellegrino Terme to attend a literary awards ceremony, where he met, among others, Eugenio Montale and Maria Bellonci. It is said that it was upon returning from this trip that he commenced writing Il Gattopardo (The Leopard), which was finished in 1956. During his life, the novel was rejected by the two publishers to whom Tomasi submitted it. In 1957 Tomasi di Lampedusa was diagnosed with lung cancer; he died on July 23 in Rome. Following a requiem in the Basilica del Sacro Cuore di Gesu in Rome, he was buried in the Capuchin cemetery of Palermo. His novel was published the year after his death; Elena Croce had sent it to the writer Giorgio Bassani, who brought it to the attention of the Feltrinelli publishing house. Il Gattopardo was

quickly recognized as a great work of contemporary Italian literature.

In 1959 Tomasi di Lampedusa was posthumously awarded the prestigious Strega Prize for the novel. Il Gattopardo follows

the family of its title character, Sicilian nobleman Don Fabrizio

Corbera, Prince of Salina, through the events of the Risorgimento.

Perhaps the most memorable line in the book is spoken by Don Fabrizio's

nephew, Tancredi, urging unsuccessfully that Don Fabrizio abandon his

allegiance to the disintegrating Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and to ally himself with Guiseppe Garibaldi and the House of Savoy:

"Unless we ourselves take a hand now, they'll foist a republic on us.

If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change." The title is rendered in English as "The Leopard", but the Italian word gattopardo refers to the American ocelot or to the African serval. Il gattopardo may

be a reference to a wildcat that was hunted to extinction in Italy in

the mid 1800s — just as Don Fabrizio was dryly contemplating the decline

and indolence of the Sicilian aristocracy. The

novel was criticised around the time of its first publication by some

literary critics for its straightforward "old fashioned" realism, a

type of Stendhalian or Tolstoyan realism that particularly irritated

neo-realists such as Elio Vittorini and Alberto Moravia. However, the novel was very popular among so-called common readers, as well as with prestigious foreign intellectuals such as Louis Aragon and E.M. Forster. In 1963 Il Gattopardo was made into a film, directed by Luchino Visconti and starring Burt Lancaster, Alain Delon and Claudia Cardinale, which won the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival. Tomasi also wrote some lesser known works: I racconti (Stories, first published 1961), Le lezioni su Stendhal (Lessons on Stendhal, privately published in 1959, published in book form in 1977), and Invito alle lettere francesi del Cinquecento (Introduction to sixteenth-century French literature,

first published 1970). He also wrote "Joy and the Law", a common piece

of literature studied in high schools today. His perceptive

commentaries on English and other foreign literature make up a larger

part of his "Opere" than his fiction.