<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Charles Babbage, 1791

- Novelist Henry Valentine Miller, 1891

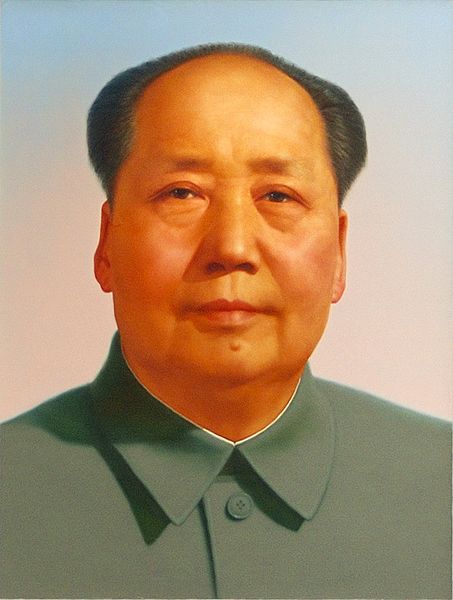

- 1st Chairman of the People's Republic of China Mao Zedong, 1893

PAGE SPONSOR

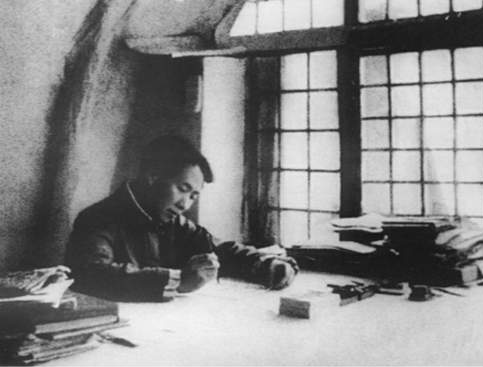

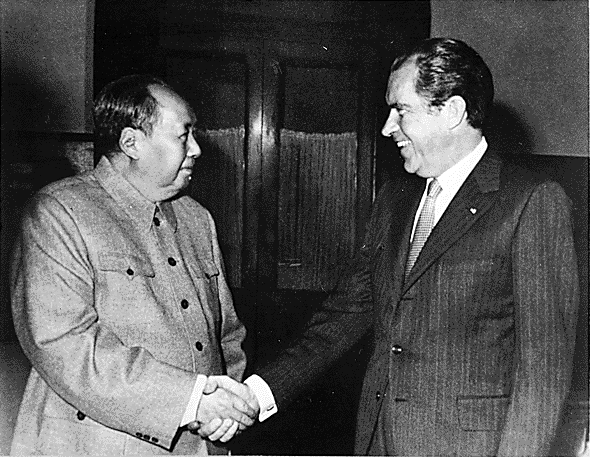

Mao Zedong (December 26, 1893 – September 9, 1976) was a Chinese revolutionary, political theorist and communist leader. He led the People's Republic of China (PRC) from its establishment in 1949 until his death in 1976. His theoretical contribution to Marxism-Leninism, military strategies, and his brand of Communist policies are now collectively known as Maoism.

Mao

remains a controversial figure to this day, with a contentious and

ever-evolving legacy. He is officially held in high regard in China as

a great revolutionary, political strategist, military mastermind, and

savior of the nation. Many Chinese also believe that through his

policies, he laid the economic, technological and cultural foundations

of modern China, transforming the country from an agrarian society into

a major world power. Additionally, Mao is viewed as a poet,

philosopher, and visionary, owing the latter primarily to the cult of personality fostered during his time in power. Mao's portrait continues to be featured prominently on Tiananmen and on all Renminbi bills. Conversely, Mao's social-political programs, such as the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, are blamed for costing millions of lives, causing severe famine and damage to the culture, society and economy of

China. Mao's policies and political purges from 1949 to 1976 are widely

believed to have caused the deaths of between 50 to 70 million people. Since Deng Xiaoping assumed power in 1978, many Maoist policies have been abandoned in favour of economic reforms. Mao is regarded as one of the most influential figures in modern world history, and named by Time Magazine as one of the 100 most important people of the 20th century. Mao was born on December 26, 1893, in Shaoshan,

Hunan province, China. His father was a poor peasant who had become a

wealthy farmer and grain dealer. At age 8 he began studying at the

village primary school, but left school at 13 to work on the family

farm. He later left the farm to continue his studies at a secondary

school in Changsha, the capital of Hunan province. When the Xinhai Revolution against the Qing Dynasty broke out in 1911 he joined the Revolutionary Army in Hunan. In the spring of 1912 the war ended, the Republic of China was founded and Mao left the army. He eventually returned to school, and in 1918 graduated from the First Provincial Normal School of Hunan. Following

his graduation, it is believed that Mao traveled with Professor Yang

Changji, his college teacher and future father-in-law, to Beijing in

1919. Professor Yang died in 1920 but prior to his death had held a

faculty position at Peking University, and at his recommendation, Mao worked as an assistant librarian at the University Library under the curatorship of Li Dazhao,

who would come to greatly influence Mao's future thought. Mao

registered as a part-time student at Beijing University and attended a

few lectures and seminars by intellectuals, such as Chen Duxiu, Hu Shi, and Qian Xuantong. During his stay in Shanghai, he engaged himself as much as possible in reading which introduced him to Communist theories. He married Yang Kaihui, Professor Yang's daughter and a fellow student, despite an existing marriage with Luo Yixiu arranged by his father at home, which Mao never acknowledged. In October 1930, the Kuomintang (KMT) captured Yang Kaihui as well as her son, Anying. The KMT imprisoned them both, and Anying was later sent to his relatives after the KMT killed his mother. At this time, Mao was living with He Zizhen, a co-worker and 17 year old girl from Yongxing, Jiangxi. Likely due to poor language skills (Mao never learned to speak Mandarin), he turned down an opportunity to study in France. On July 23, 1921, Mao, age 27, attended the first session of the National Congress of the Communist Party of China in

Shanghai. Two years later, he was elected as one of the five commissars

of the Central Committee of the Party during the third Congress

session. Later that year, Mao returned to Hunan at the instruction of

the CPC Central Committee and the Kuomintang Central Committee to organize the Hunan branch of the Kuomintang. In

1924, he was a delegate to the first National Conference of the

Kuomintang, where he was elected an Alternate Executive of the Central

Committee. In 1924, he became an Executive of the Shanghai branch of

the Kuomintang and Secretary of the Organization Department. For

a while, Mao remained in Shanghai, an important city that the CPC

emphasized for the Revolution. However, the Party encountered major

difficulties organizing labor union movements and building a

relationship with its nationalist ally, the KMT. The Party had become

poor, and Mao became disillusioned with the revolution and moved back

to Shaoshan. During his stay at home, Mao's interest in the revolution

was rekindled after hearing of the 1925 uprisings in Shanghai and

Guangzhou. His political ambitions returned, and he then went to

Guangdong, the base of the Kuomintang, to take part in the preparations

for the second session of the National Congress of Kuomintang. In

October 1925, Mao became acting Propaganda Director of the Kuomintang. In

early 1927, Mao returned to Hunan where, in an urgent meeting held by

the Communist Party, he made a report based on his investigations of

the peasant uprisings in the wake of the Northern Expedition. This is considered the initial and decisive step towards the successful application of Mao's revolutionary theories. Mao

had a strong interest in the political system, encouraged by his

father. His two most famous essays, both from 1937, 'On Contradiction'

and 'On Practice', are concerned with the practical strategies of a

revolutionary movement and stress the importance of practical,

grass-roots knowledge, obtained through experience. Both

essays reflect the guerilla roots of Maoism in the need to build up

support in the countryside against a Japanese occupying force and

emphasise the need to win over hearts and minds through 'education'.

The essays, reproduced later as part of the 'Red Book',

warn against the behaviour of the blindfolded man trying to catch

sparrows, and the 'Imperial envoy' descending from his carriage to

'spout opinions' . After

graduating from Hunan Normal School, the highest level of schooling

available in his province, Mao spent six months studying independently.

Mao was first introduced to communism while working at Peking University,

and in 1921 he attended the organizational meeting of the Communist

Party of China (or CPC). He first encountered Marxism while he worked

as a library assistant at Peking University. Other important influences on Mao were the Russian revolution and, according to some scholars, the Chinese literary works: Outlaws of the Marsh and Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Mao sought to subvert the alliance of imperialism and feudalism in

China. He thought the KMT to be both economically and politically

vulnerable and thus that the revolution could not be steered by

Nationalists. Throughout

the 1920s, Mao led several labour struggles based upon his studies of

the propagation and organization of the contemporary labour movements. However, these struggles were successfully subdued by the government, and Mao fled from Changsha, Hunan, after he was labeled a radical activist.

He pondered these failures and finally realized that industrial workers

were unable to lead the revolution because they made up only a small

portion of China's population, and unarmed labour struggles could not

resolve the problems of imperial and feudal suppression. Mao

began to depend on Chinese peasants who later became staunch supporters

of his theory of violent revolution. This dependence on the rural

rather than the urban proletariat to instigate violent revolution

distinguished Mao from his predecessors and contemporaries. Mao himself

was from a peasant family, and thus he cultivated his reputation among

the farmers and peasants and introduced them to Marxism. In 1927, Mao conducted the famous Autumn Harvest Uprising in

Changsha, as commander-in-chief. Mao led an army, called the

"Revolutionary Army of Workers and Peasants", which was defeated and

scattered after fierce battles. Afterwards, the exhausted troops were

forced to leave Hunan for Sanwan, Jiangxi, where Mao re-organized the

scattered soldiers, rearranging the military division into smaller

regiments. Mao also ordered that each company must have a party branch office with a commissar as

its leader who would give political instructions based upon superior

mandates. This military rearrangement in Sanwan, Jiangxi, initiated the

CPC's absolute control over its military force and has been considered

to have the most fundamental and profound impact upon the Chinese

revolution. Later, they moved to the Jinggang Mountains, Jiangxi. In

the Jinggang Mountains, Mao persuaded two local insurgent leaders to

pledge their allegiance to him. There, Mao joined his army with that of Zhu De, creating the Workers' and Peasants' Red Army of China, Red Army in short. Mao's tactics were strongly based on that of the Spanish Guerillas during the Napoleonic Wars. From 1931 to 1934, Mao helped establish the Soviet Republic of China and was elected Chairman of this small republic in the mountainous areas in Jiangxi. Here, Mao was married to He Zizhen. His previous wife, Yang Kaihui, had been arrested and executed in 1930, just three years after their departure. In

Jiangxi, Mao's authoritative domination, especially that of the

military force, was challenged by the Jiangxi branch of the CPC and

military officers. Mao's opponents, among whom the most prominent was

Li Wenlin, the founder of the CPC's branch and Red Army in Jiangxi,

were against Mao's land policies and proposals to reform the local

party branch and army leadership. Mao reacted first by accusing the

opponents of opportunism and kulakism and then set off a series of systematic suppressions of them. Under the direction of Mao, it is reported that horrible methods of torture took place and given names such as 'sitting in a sedan chair', 'airplane ride', 'toad-drinking water', and 'monkey pulling reins.' The wives of several suspects had their breasts cut open and their genitals burned. Short (2001) estimates that tens of thousands of suspected enemies, perhaps as many as 186,000, were killed during this purge. Critics accuse Mao's authority in Jiangxi of being secured and reassured through the revolutionary terrorism, or red terrorism. Mao, with the help of Zhu De,

built a modest but effective army, undertook experiments in rural

reform and government, and provided refuge for Communists fleeing the

rightist purges in the cities. Mao's methods are normally referred to

as Guerrilla warfare; but he himself made a distinction between

guerrilla warfare (youji zhan) and Mobile Warfare (yundong zhan).

Mao's

Guerrilla Warfare and Mobile Warfare was based upon the fact of the

poor armament and military training of the Red Army which consisted

mainly of impoverished peasants, who, however, were all encouraged by

revolutionary passions and aspiring after a communist utopia. Around 1930, there had been more than ten regions, usually entitled "soviet areas", under control of the CPC. The relative prosperity of "soviet areas" startled and worried Chiang Kai-shek,

chairman of the Kuomintang government, who waged five waves of

besieging campaigns against the "central soviet area." More than one

million Kuomintang soldiers were involved in these five campaigns, four

of which were defeated by the Red Army led by Mao. By June 1932 (the

height of its power), the Red Army had no less than 45,000 soldiers,

with a further 200,000 local militia acting as a subsidiary force. Under

increasing pressure from the KMT encirclement campaigns, there was a

struggle for power within the Communist leadership. Mao was removed

from his important positions and replaced by individuals (including Zhou Enlai) who appeared loyal to the orthodox line advocated by Moscow and represented within the CPC by a group known as the 28 Bolsheviks. Chiang,

who had earlier assumed nominal control of China due in part to the

Northern Expedition, was determined to eliminate the Communists. By

October 1934, he had them surrounded, prompting them to engage in the "Long March," a retreat from Jiangxi in the southeast to Shaanxi in

the northwest of China. It was during this 9,600 kilometer

(5,965 mile), year-long journey that Mao emerged as the top

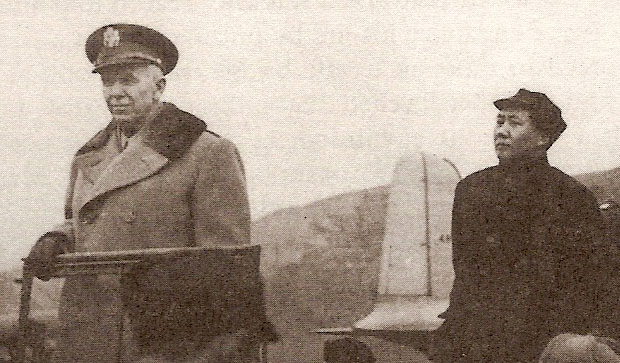

Communist leader, aided by the Zunyi Conference and the defection of Zhou Enlai to Mao's side. At this Conference, Mao entered the Standing Committee of the Politburo of the Communist Party of China. According to the standard Chinese Communist Party line, from his base in Yan'an, Mao led the Communist resistance against the Japanese in the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937 – 1945). However, Mao further consolidated power over the Communist Party in 1942 by launching the Shu Fan movement, or "Rectification" campaign against rival CPC members such as Wang Ming, Wang Shiwei, and Ding Ling. Also while in Yan'an, Mao divorced He Zizhen and married the actress Lan Ping, who would become known as Jiang Qing. During the Sino-Japanese War, Mao Zedong's military strategies, laid out in On Guerrilla Warfare were

opposed by both Chiang Kai-shek and the United States. The US regarded

Chiang as an important ally, able to help shorten the war by engaging

the Japanese occupiers in China. Chiang, in contrast, sought to build

the ROC army for the certain conflict with Mao's communist forces after

the end of World War II. This fact was not understood well in the US,

and precious lend-lease armaments continued to be allocated to the Kuomintang. In

turn, Mao spent part of the war (as to whether it was most or only a

little is disputed) fighting the Kuomintang for control of certain

parts of China. Both the Communists and Nationalists have been

criticised for fighting amongst themselves rather than allying against

the Japanese Imperial Army. Some argue, however, that the Nationalists

were better equipped and fought more against Japan. In 1944, the Americans sent a special diplomatic envoy, called the Dixie Mission, to the Communist Party of China. According to Edwin Moise, in Modern China: A History: After the end of World War II, the U.S. continued to support Chiang Kai-shek, now openly against the People's Liberation Army led by Mao Zedong in the civil war for

control of China. The U.S. support was part of its view to contain and

defeat world communism. Likewise, the Soviet Union gave quasi-covert

support to Mao (acting as a concerned neighbor more than a military

ally, to avoid open conflict with the U.S.) and gave large supplies of

arms to the Communist Party of China, although newer Chinese records

indicate the Soviet "supplies" were not as large as previously

believed, and consistently fell short of the promised amount of aid. In 1948, the People’s Liberation Army starved out the Kuomintang forces occupying the city of Changchun. At least 160,000 civilians are believed to have perished during the siege, which lasted from June until October. PLA lieutenant colonel Zhang Zhenglu, who documented the siege in his book White Snow, Red Blood, compared it to Hiroshima: “The casualties were about the same. Hiroshima took nine seconds; Changchun took five months.” On

January 21, 1949, Kuomintang forces suffered massive losses against

Mao's forces. In the early morning of December 10, 1949, PLA troops

laid siege to Chengdu, the last KMT-occupied city in mainland China, and Chiang Kai-shek evacuated from the mainland to Taiwan (Formosa) that same day. The

People's Republic of China was established on October 1, 1949. It was

the culmination of over two decades of civil and international war.

From 1954 to 1959, Mao was the Chairman of the PRC. During this period, Mao was called Chairman Mao or the Great Leader Chairman Mao. The

Communist Party assumed control of all media in the country and used it

to promote the image of Mao and the Party. The Nationalists under

General Chiang Kai-Shek were vilified as were countries such as the

United States of America and Japan. The Chinese people were exhorted to

devote themselves to build and strengthen their country through

Communist ideology. In his speech declaring the foundation of the PRC,

Mao is famously said to have announced: "The Chinese people have stood

up" (though whether he actually said it is disputed). Mao took up residence in Zhongnanhai, a compound next to the Forbidden City in

Beijing, and there he ordered the construction of an indoor swimming

pool and other buildings. Mao often did his work either in bed or by

the side of the pool, preferring not to wear formal clothes unless

absolutely necessary, according to Dr. Li Zhisui, his personal physician. (Li's book, The Private Life of Chairman Mao, is regarded as controversial, especially by those sympathetic to Mao.) In October 1950, Mao made the decision to send the People's Volunteer Army into

Korea and fought against the United Nations forces led by the U.S.

Historical records showed that Mao directed the PVA campaigns in the Korean War to the minute details. Along with Land reform,

during which significant numbers of landlords were beaten to death at

mass meetings organized by the Communist Party as land was taken from

them and given to poorer peasants, there was also the Campaign to Suppress Counter revolutionaries, which

involved public executions targeting mainly former Kuomintang

officials, businessmen accused of "disturbing" the market, former

employees of Western companies and intellectuals whose loyalty was

suspect. The U.S. State department in

1976 estimated that there may have been a million killed in the land

reform, 800,000 killed in the counter revolutionary campaign. Mao himself claimed that a total of 700,000 people were executed during the years 1949–53. However,

because there was a policy to select "at least one landlord, and

usually several, in virtually every village for public execution", the number of deaths range between 2 million and 5 million. In addition, at least 1.5 million people, perhaps as many as 4 to 6 million, were sent to "reform through labour" camps where many perished. Mao played a personal role in organizing the mass repressions and established a system of execution quotas, which were often exceeded. Nevertheless he defended these killings as necessary for the securing of power. Starting

in 1951, Mao initiated two successive movements in an effort to rid

urban areas of corruption by targeting wealthy capitalists and

political opponents, known as the three-anti/five-anti campaigns.

A climate of raw terror developed as workers denounced their bosses,

wives turned on their husbands, and children informed on their parents;

the victims often being humiliated at struggle sessions,

a method designed to intimidate and terrify people to the maximum. Mao

insisted that minor offenders be criticized and reformed or sent to

labor camps, "while the worst among them should be shot." These campaigns took several hundred thousand additional lives, the vast majority via suicide. In

Shanghai, people jumping to their deaths became so commonplace that

residents avoided walking on the pavement near skyscrapers for fear

that suicides might land on them. Some

biographers have pointed out that driving those perceived as enemies to

suicide was a common tactic during the Mao-era. For example, in his

biography of Mao, Philip Short notes that in the Yan'an Rectification Movement, Mao gave explicit instructions that "no cadre is to be killed," but in practice allowed security chief Kang Sheng to drive opponents to suicide and that "this pattern was repeated throughout his leadership of the People's Republic." Following

the consolidation of power, Mao launched the First Five-Year Plan

(1953–8). The plan aimed to end Chinese dependence upon agriculture in

order to become a world power. With the Soviet Union's

assistance, new industrial plants were built and agricultural

production eventually fell to a point where industry was beginning to

produce enough capital that China no longer needed the USSR's support.

The success of the First Five Year Plan was to encourage Mao to

instigate the Second Five Year Plan, the Great Leap Forward, in 1958.

Mao also launched a phase of rapid collectivization. The CPC introduced price controls as well as a Chinese character simplification aimed at increasing literacy. Large scale industrialization projects were also undertaken. Programs pursued during this time include the Hundred Flowers Campaign,

in which Mao indicated his supposed willingness to consider different

opinions about how China should be governed. Given the freedom to

express themselves, liberal and intellectual Chinese began opposing the

Communist Party and questioning its leadership. This was initially

tolerated and encouraged. After a few months, Mao's government reversed

its policy and persecuted those, totalling perhaps 500,000, who

criticized, as well as those who were merely alleged to have

criticized, the Party in what is called the Anti-Rightist Movement. Authors such as Jung Chang have alleged that the Hundred Flowers Campaign was merely a ruse to root out "dangerous" thinking. Others

such as Dr Li Zhisui have suggested that Mao had initially seen the

policy as a way of weakening those within his party who opposed him,

but was surprised by the extent of criticism and the fact that it began

to be directed at his own leadership. It

was only then that he used it as a method of identifying and

subsequently persecuting those critical of his government. The Hundred

Flowers movement led to the condemnation, silencing, and death of many

citizens, also linked to Mao's Anti-Rightist Movement, with death tolls

possibly in the millions. In January 1958, Mao Zedong launched the second Five-Year Plan known as the Great Leap Forward,

a plan intended as an alternative model for economic growth to the

Soviet model focusing on heavy industry that was advocated by others in

the party. Under this economic program, the relatively small

agricultural collectives which had been formed to date were rapidly

merged into far larger people's communes,

and many of the peasants ordered to work on massive infrastructure

projects and the small-scale production of iron and steel. Some private

food production was banned; livestock and farm implements were brought

under collective ownership. Under

the Great Leap Forward, Mao and other party leaders ordered the

implementation of a variety of unproven and unscientific new

agricultural techniques by the new communes. Combined with the

diversion of labor to steel production and infrastructure projects and

the reduced personal incentives under a commune system this led to an

approximately 15% drop in grain production in 1959 followed by further

10% reduction in 1960 and no recovery in 1961. In

an effort to win favor with their superiors and avoid being purged,

each layer in the party hierarchy exaggerated the amount of grain

produced under them and based on the fabricated success, party cadres

were ordered to requisition a disproportionately high amount of the

true harvest for state use primarily in the cities and urban areas but

also for export. The net result, which was compounded in some areas by

drought and in others by floods, was that the rural peasants were not

left enough to eat and many millions starved to death in the largest famine in human history.

This famine was a direct cause of the death of tens of millions of

Chinese peasants between 1959 and 1962. Further, many children who

became emaciated and malnourished during years of hardship and struggle

for survival, died shortly after the Great Leap Forward came to an end

in 1962. The

extent of Mao's knowledge as to the severity of the situation has been

disputed. According to some, most notably Dr. Li Zhisui, Mao was not

aware of anything more than a mild food and general supply shortage

until late 1959. "But

I do not think that when he spoke on July 2, 1959, he knew how bad the

disaster had become, and he believed the party was doing everything it

could to manage the situation" Jung Chang and Jon Halliday, in Mao: the Unknown Story,

alleged that Mao knew of the vast suffering and that he was dismissive

of it, blaming bad weather or other officials for the famine. "Although

slaughter was not his purpose with the Leap, he was more than ready for

myriad deaths to result, and hinted to his top echelon that they should

not be too shocked if they happened (438–439)." In Hungry Ghosts, Jasper Becker notes

that Mao was dismissive of reports he received of food shortages in the

countryside and refused to change course, believing that peasants were

lying and that rightists and kulaks were hoarding grain. He refused to open state granaries, and instead launched a series of "anti-grain concealment" drives that resulted in numerous purges and suicides. Other violent campaigns followed in which party leaders went from village to

village in search of hidden food reserves, and not only grain, as Mao

issued quotas for pigs, chickens, ducks and eggs. Many peasants accused

of hiding food were tortured and beaten to death. Whatever

the case, the Great Leap Forward led to millions of deaths in China.

Mao lost esteem among many of the top party cadres and was eventually

forced to abandon the policy in 1962, also losing some political power

to moderate leaders, notably Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping.

However, Mao and national propaganda claimed that he was only partly to

blame. As a result, he was able to remain Chairman of the Communist

Party, with the Presidency transferred to Liu Shaoqi. The

Great Leap Forward was a disaster for China. Although the steel quotas

were officially reached, almost all of it made in the countryside was

useless lumps of iron, as it had been made from assorted scrap metal in

home made furnaces with no reliable source of fuel such as coal.

According to Zhang Rongmei, a geometry teacher in rural Shanghai during

the Great Leap Forward: "We

took all the furniture, pots, and pans we had in our house, and all our

neighbors did likewise. We put all everything in a big fire and melted

down all the metal." Moreover,

most of the dams, canals and other infrastructure projects, which

millions of peasants and prisoners had been forced to toil on and in

many cases die for, proved useless as they had been built without the

input of trained engineers, whom Mao had rejected on ideological

grounds. The worst of the famine was steered towards enemies of the state, much like during the 1932–33 famine in the USSR. As Jasper Becker explains: "The most vulnerable section of China's population, around five per cent, were those whom Mao called 'enemies of the people'.

Anyone who had in previous campaigns of repression been labeled a

'black element' was given the lowest priority in the allocation of

food. Landlords, rich peasants, former members of the nationalist

regime, religious leaders, rightists, counter-revolutionaries and the

families of such individuals died in the greatest numbers." At the Lushan Conference in July/August 1959, several leaders expressed concern that the Great Leap Forward was not as successful as planned. The most direct of these was Minister of Defence and Korean War General Peng Dehuai.

Mao, fearing loss of his position, orchestrated a purge of Peng and his

supporters, stifling criticism of the Great Leap policies. Senior

officials who reported the truth of the famine to Mao were branded as

"right opportunists." A

campaign against right opportunism was launched and resulted in party

members and ordinary peasants being sent to camps where many would

subsequently die in the famine. Years later the CPC would conclude that

6 million people were wrongly punished in the campaign. There

is a great deal of controversy over the number of deaths by starvation

during the Great Leap Forward. Until the mid 1980s, when official

census figures were finally published by the Chinese Government, little

was known about the scale of the disaster in the Chinese countryside,

as the handful of Western observers allowed access during this time had

been restricted to model villages where they were deceived into

believing that Great Leap Forward had been a great success. There was

also an assumption that the flow of individual reports of starvation

that had been reaching the West, primarily through Hong Kong and

Taiwan, must be localized or exaggerated as China was continuing to

claim record harvests and was a net exporter of grain through the

period. Because Mao wanted to pay back early to the Soviets debts

totaling 1.973 billion yuan from 1960 to 1962, exports increased by 50%, and fellow Communist regimes in North Korea, North Vietnam and Albania were provided grain free of charge. Censuses

were carried out in China in 1953, 1964 and 1982. The first attempt to

analyse this data in order to estimate the number of famine deaths was

carried out by American demographer Dr Judith Banister and published in

1984. Given the lengthy gaps between the censuses and doubts over the

reliability of the data, an accurate figure is difficult to ascertain.

Nevertheless, Banister concluded that the official data implied that

around 15 million excess deaths incurred in China during 1958–61 and

that based on her modelling of Chinese demographics during the period

and taking account of assumed underreporting during the famine years,

the figure was around 30 million. The official statistic is 20 million

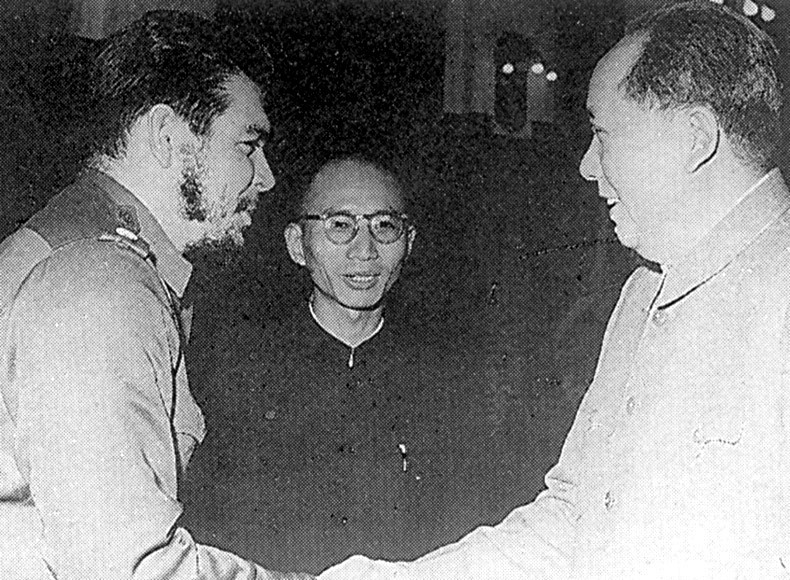

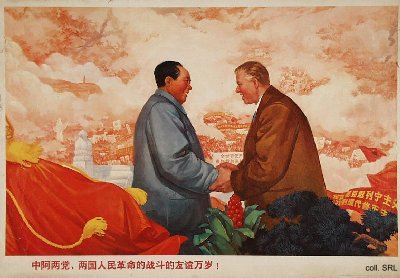

deaths, as given by Hu Yaobang. Yang Jisheng, a former Xinhua News Agency reporter who had privileged access and connections available to no other scholars, estimates a death toll of 36 million. Various other sources have put the figure between 20 and 46 million. On the international front, the period was dominated by the further isolation of China, due to start of the Sino-Soviet split which resulted in Khrushchev withdrawing

all Soviet technical experts and aid from the country. The split was

triggered by border disputes, and arguments over the control and

direction of world communism, and other disputes pertaining to foreign

policy. Most of the problems regarding communist unity resulted from

the death of Stalin and his replacement by Khrushchev. Stalin had established himself as the successor of "correct" Marxist thought well before Mao controlled the Communist Party of China, and therefore Mao never challenged the suitability of any Stalinist

doctrine (at least while Stalin was alive). Upon the death of Stalin,

Mao believed (perhaps because of seniority) that the leadership of the

"correct" Marxist doctrine would fall to him. The resulting tension

between Khrushchev (at the head of a politically/militarily superior

government), and Mao (believing he had a superior understanding of

Marxist ideology) eroded the previous patron-client relationship

between the CPSU and

CPC. In China, the formerly favourable Soviets were now denounced as

"revisionists" and listed alongside "American imperialism" as movements

to oppose. Partly surrounded by hostile American military bases (reaching from South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan), China was now confronted with a new Soviet threat

from the north and west. Both the internal crisis and the external

threat called for extraordinary statesmanship from Mao, but as China

entered the new decade the statesmen of the People's Republic were in

hostile confrontation with each other. At

a large Communist Party conference in Beijing in January 1962, called

the "Conference of the Seven Thousand," State President Liu Shaoqi

denounced the Great Leap Forward as responsible for widespread famine. The overwhelming majority of delegates expressed agreement, but Defense Minister Lin Biao staunchly defended Mao. A brief period of liberalization followed while Mao and Lin plotted a comeback. Liu and Deng Xiaoping rescued

the economy by disbanding the people's communes, introducing elements

of private control of peasant smallholdings and importing grain from

Canada and Australia to mitigate the worst effects of famine. Mao

was concerned with the nature of post 1949 China. He saw that the

revolution had replaced an old elite, with a new one. He was concerned

that those in power were becoming estranged from the people they were

supposed to serve. Corruption was also a concern. Mao thought that a

greater threat to China was not from forces outside of the Communist

Party, but from people from within who would subvert it and create a

new elite who would control the masses of the population, and not serve

them (capitalism from within). He thought that a renewal was required,

a revolution of culture that would unseat and unsettle the "ruling

class" and keep China in a state of 'perpetual revolution' that served

the interests of the majority, not a tiny elite. There are political aspects to this period as well. Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping's

prominence gradually became more powerful. Liu and Deng, then the State

President and General Secretary, respectively, had favored the idea

that Mao should be removed from actual power but maintain his

ceremonial and symbolic role, with the party upholding all of his

positive contributions to the revolution. They attempted to marginalize

Mao by taking control of economic policy and asserting themselves

politically as well. Many claim that Mao responded to Liu and Deng's

movements by launching the Cultural Revolution in 1966, although the case for this is perhaps overstated. Believing

that certain liberal bourgeois elements of society continued to

threaten the socialist framework, groups of young people known as the Red Guards struggled

against authorities at all levels of society and even set up their own

tribunals. Chaos reigned in many parts of the country, and millions

were persecuted, including a famous philosopher, Chen Yuen. Mao is said

to have ordered that no physical harm come to anyone, but that was not

always the case. During the Cultural Revolution, the schools in China

were closed and the young intellectuals living in cities were ordered

to the countryside to be "re-educated" by the peasants, where they

performed hard manual labor and other work. The

Revolution led to the destruction of much of China's traditional

cultural heritage and the imprisonment of a huge number of Chinese

citizens, as well as creating general economic and social chaos in the

country. Millions of lives were ruined during this period, as the

Cultural Revolution pierced into every part of Chinese life, depicted

by such Chinese films as To Live, The Blue Kite and Farewell My Concubine. It is estimated that hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, perished in the violence of the Cultural Revolution. When Mao was informed of such losses, particularly that people had been driven to suicide, he is alleged to have commented: "People who try to commit suicide — don't attempt to save

them! . . . China is such a populous nation, it is not

as if we cannot do without a few people." The authorities allowed the Red Guards to abuse and kill opponents of the regime. Said Xie Fuzhi, national police chief: "Don't say it is wrong of them to beat up bad persons: if in anger they beat someone to death, then so be it." As a result, in August and September 1966, there were 1,772 people murdered in Beijing alone. It was during this period that Mao chose Lin Biao,

who seemed to echo all of Mao's ideas, to become his successor. Lin was

later officially named as Mao's successor. By 1971, however, a divide

between the two men became apparent. Official history in China states

that Lin was planning a military coup or an assassination attempt on

Mao. Lin Biao died in a plane crash over the air space of Mongolia,

presumably on his way to flee China, probably anticipating his arrest.

The CPC declared that Lin was planning to depose Mao, and posthumously

expelled Lin from the party. At this time, Mao lost trust in many of

the top CPC figures. The highest-ranking Soviet Bloc intelligence

defector, Lt. Gen. Ion Mihai Pacepa described his conversation with Nicolae Ceauşescu who told him about a plot to kill Mao Zedong with the help of Lin Biao organized by KGB. In

1969, Mao declared the Cultural Revolution to be over, although the

official history of the People's Republic of China marks the end of the

Cultural Revolution in 1976 with Mao's death. In the last years of his

life, Mao was faced with declining health due to either Parkinson's disease or, according to Li Zhisui, motor neurone disease,

as well as lung ailments due to smoking and heart trouble. Some also

attributed Mao's decline in health to the betrayal of Lin Biao. Mao

remained passive as various factions within the Communist Party

mobilized for the power struggle anticipated after his death. This

period is often looked at in official circles in China and in the west

as a great stagnation or even of reversal for China. While many —

an estimated 100 million — did suffer, some

scholars, such as Lee Feigon and Mobo Gao, claim there were many great

advances, and in some sectors the Chinese economy continued to

outperform the west. They

actually go so far as to conclude that the Cultural Revolution period

actually laid the foundation for the spectacular growth that continues

in China. During the Cultural Revolution, China exploded its first

H-Bomb (1967), launched the Dong Fang Hong satellite (January 30,

1970), commissioned its first nuclear submarines and made various

advances in science and technology. Health care was free, and living

standards in the country side continued to improve. At

five o'clock in the afternoon of September 2, 1976, Mao suffered a

heart attack, far more severe than his previous two and affecting a

much larger area of his heart. X rays indicated that his lung infection

had worsened, and his urine output dropped to less than 300 cc a day.

Mao was awake and alert throughout the crisis and asked several times

whether he was in danger. His condition continued to fluctuate and his

life hung in the balance. Three

days later, on September 5, Mao's condition was still critical, and Hua

Guofeng called Jiang Qing back from her trip. She spent only a few

moments in Building 202 (where Mao was staying) before returning to her

own residence in the Spring Lotus Chamber. On

the afternoon of September 7, Mao took a turn for the worse. Jiang Qing

went to Building 202 where she learned the news. Mao had just fallen

asleep and needed the rest, but she insisted on rubbing his back and

moving his limbs, and she sprinkled powder on his body. The medical

team protested that the dust from the powder was not good for his

lungs, but she instructed the nurses on duty to follow her example

later. The next morning, September 8, she went again. She demanded the

medical staff to change Mao's sleeping position, claiming that he had

been lying too long on his left side. The doctor on duty objected,

knowing that he could breathe only on his left side, but she had him

moved nonetheless. Mao's

breathing stopped and his face turned blue. Jiang Qing left the room

while the medical staff put him on a respirator and performed emergency

cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Mao barely revived and Hua Guofeng urged

Jiang Qing not to interfere further with the doctors' work, as her

actions were detrimental to Mao's health and helped cause his death

faster. Mao's organs were failing and he was taken off the life support

a few minutes after midnight. September 9 was chosen because it was an

easy day to remember. Mao had been in poor health for several years and

had declined visibly for at least 6 months prior to his death. His body lay in state at the Great Hall of the People. A memorial service was held in Tiananmen Square on September 18, 1976. There was a three minute silence observed during this service. His body was later placed into the Mausoleum of Mao Zedong,

even though he had wished to be cremated and had been one of the first

high-ranking officials to sign the "Proposal that all Central Leaders be Cremated after Death" in November 1956.