<Back to Index>

- Chemist, Mineralogist and Zoologist Alexandre Brongniart, 1770

- Painter Carl Spitzweg, 1808

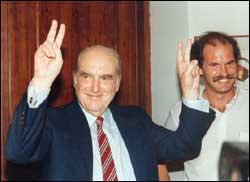

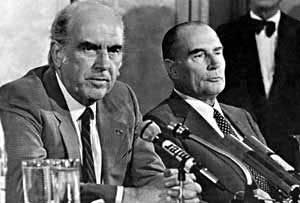

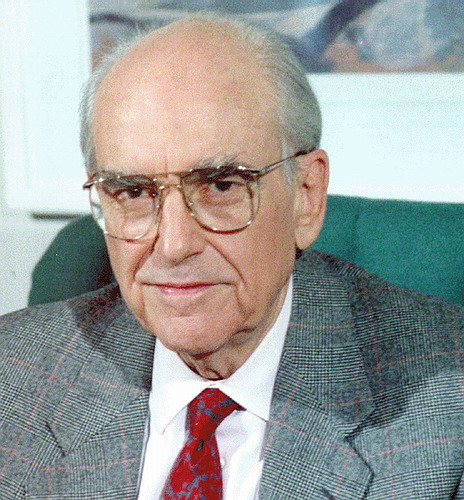

- Prime Minister of Greece Andreas Papandreou, 1919

Andreas Papandreou (Greek: Ανδρέας Παπανδρέου) (5 February 1919– 23 June 1996) was a Greek economist, a socialist politician and a dominant figure in Greek politics. He served two terms as Prime Minister of Greece (21 October 1981, to 2 July 1989, and 13 October 1993, to 22 January 1996). In 1999, Papandreou was posthumously awarded the Swedish Order of the Polar Star.

Papandreou was born on the island of Chios, Greece, the son of the leading Greek liberal politician George Papandreou. His mother, born Zofia (Sofia) Mineyko, was half Polish. Before university, he attended Athens College a leading private school in Greece. He attended the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens from 1937 till 1938 when, during the quasi-Fascist Metaxas dictatorship, he was arrested for purported Trotskyism. Following representations by his father, he was allowed to leave for the US.

In 1942, Papandreou enrolled at Harvard University, where he completed a doctorate in economics. In 1943, he joined America's war effort and volunteered for the US Navy where he served as a nurse at Bethesda Hospital for war wounded, and became a United States citizen.

He returned to Harvard in 1946 and served as a lecturer and associate

professor until 1947. He then held professorships at the University of Minnesota, Northwestern University, the University of California, Berkeley (where he was chair of the Department of Economics), Stockholm University and York University in Toronto, Canada. In 1948, he entered into a relationship with University of Minnesota journalism student Margaret Chant. After

Chant obtained a divorce and after his own divorce with Christina

Rasia, his first wife, Papandreou and Chant were married in 1951. They

had three sons and a daughter. Papandreou also had a daughter out of wedlock living in Sweden. Papandreou returned to Greece in 1959, where he headed an economic development research program, by invitation of Prime Minister Konstantinos Karamanlis.

In 1960, he was appointed Chairman of the Board of Directors and

General Director of the Athens Economic Research Center, and Advisor to

the Bank of Greece. In 1963, his father George Papandreou, head of the Center Union,

became Prime Minister of Greece. Andreas became his chief economic

advisor. He renounced his American citizenship and was elected to the Greek Parliament in

the Greek legislative election, 1964. He immediately became Minister to

the First Ministry of State (in effect, assistant Prime Minister). Papandreou

took publicly a neutral stand on the Cold War and wished for Greece to

be more independent from the USA. He also criticized the massive

presence of American military and intelligence in Greece, and sought to

remove senior officers with "anti-democratic tendencies" from the Greek

military. In 1965, while the "Aspida"

conspiracy within the Army, alleged by the political opposition to

involve Andreas personally, was being investigated, George Papandreou

moved to fire the defense minister and assume the post himself. King

Constantine refused to endorse this move and essentially forced George

Papandreou's resignation. Greece entered a period of political

polarisation and instability, which ended with the coup d'état of 21 April 1967. When the Greek Colonels led by Georgios Papadopoulos seized

power in April 1967, Andreas was incarcerated while his father George

Papandreou was put under house arrest. George Papandreou, already at

advanced age, died in 1968. Under American pressure, the military regime

released Andreas on condition that he leave the country. Papandreou

then moved to Sweden with his wife, four children, and mother. There he accepted a post at Stockholm University. In Paris, while in exile, Andreas Papandreou formed an "anti-dictatorship organization", the Panhellenic Liberation Movement (PAK),

and toured the world rallying opposition to the Greek military regime.

Despite his former American citizenship and academic career in the

United States, Papandreou held the Central Intelligence Agency responsible for the 1967 coup and became increasingly critical of the U.S. Government. In the early 1970s,

during the latter phase of the dictatorship in Greece, Papandreou,

along with most leading Greek politicians, in exile or in Greece,

opposed the process of political normalisation attempted by Georgios Papadopoulos and his appointed PM, Spyros Markezinis.

In August 6, 1974, Andreas Papandreou called an extraordinary meeting

of the National Congress of PAK in Winterthur, Switzerland, which

decided its dissolution without announcing it publicly. Papandreou returned to Greece after the fall of the junta in 1974, during metapolitefsi, and formed a new "radical" party, the Panhellenic Socialist Movement, or PASOK. Most of his former PAK companions, as well as members of other anti-dictatorial groups such as the Democratic Defense joined in the new party. He also testified in the first of the Greek Junta Trials about the alleged involvement of the junta with the CIA. At

that year's elections, PASOK received only 13.5% of the vote, but in

1977 it polled 25%, and Papandreou became Leader of the Opposition. At

the 1981 elections, PASOK won a landslide victory over the conservative New Democracy Party, and Papandreou became Greece's first socialist Prime Minister. In

office, Papandreou backtracked from much of his campaign rhetoric and

followed a more conventional approach. Greece did not withdraw from

NATO, United States troops and military bases were not ordered out of

Greece, and Greek membership in the European Economic Community continued.

In domestic politics, Papandreou's government carried through sweeping

reforms of social policy by expanding health care coverage (the

"National Health System" was instituted), promoting state-subsidized

tourism for lower-income families, and funding social establishments

for the elderly. In a move strongly opposed by the Greek Orthodox

Church, Papandreou introduced, for the first time in Greece, the

process of civil marriage. Also, under PASOK, the

Greek State appropriated real estate properties previously owned

by the Church. Papandreou introduced various reforms in the

administration and curriculum of the Greek educational system, allowing

students to participate in the election process for their professors

and deans in the university, and abolishing tenure. Papandreou

was comfortably re-elected in 1985 with 46% of the vote, but, in the

years to follow, his premiership became increasingly clouded by

controversy and scandal. In 1989, he divorced his wife Margaret Papandreou and married Dimitra Liani, while in the same year he was indicted by Parliament in connection with a $200M Bank of Crete embezzlement

scandal, and was accused of facilitating the embezzlement by ordering

state corporations to transfer their holdings to the Bank of Crete,

where the interest was allegedly skimmed off to benefit PASOK, and

possibly some of its highest functionaries. Following the many

repercussions of the so-called Koskotas scandal,

the 1989 elections produced a deadlock, leading to a prolonged

political crisis. Papandreou's PASOK's won 40% of the popular vote,

compared to the rival New Democracy's 46%, and, due to changes made in

electoral law one year before the elections by the then reigning PASOK

administration, New Democracy was not able to form a government. In the

wake of three consecutive elections between 1989 and 1990, the New

Democracy leader, Constantine Mitsotakis,

eventually received sufficient support to form a government. In January

1992, Papandreou himself was cleared of any wrongdoing in the Koskotas

scandal after a 7-6 vote in the specially convened High Court trial,

ordered by the Greek parliament, with the support of both main parties,

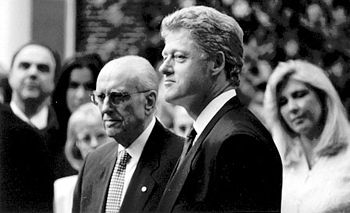

New Democracy and PASOK. Papandreou confounded his critics by

winning the next general elections of October 1993 ; however, his

fragile health kept him from exercising firm political leadership. He

was hospitalized with advanced heart disease and kidney failure on 20

November 1995 and finally retired from office on 16 January 1996. He

died on 23 June 1996, with his funeral procession producing an

outpouring of public emotion.