<Back to Index>

- Naturalist Charles Robert Darwin, 1809

- Architect Étienne-Louis Boullée, 1728

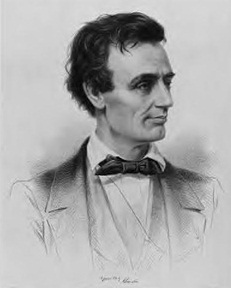

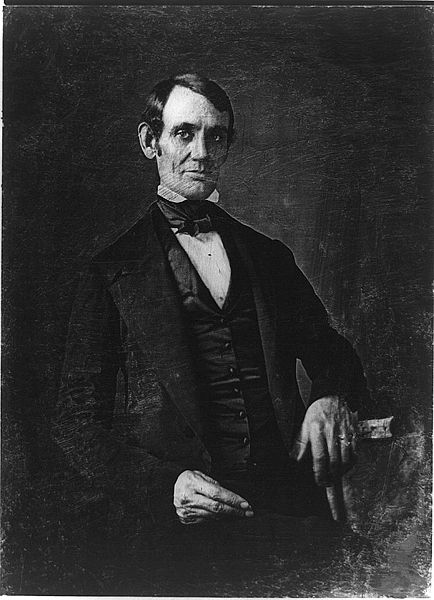

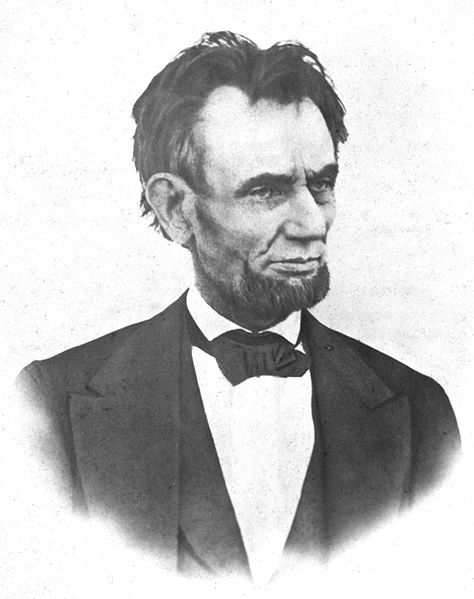

- 16th President of the United States Abraham Lincoln, 1809

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) served as the 16th President of the United States from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through its greatest internal crisis, the American Civil War, preserving the Union and ending slavery. Before his election in 1860 as the first Republican president, Lincoln had been a country lawyer, an Illinois state legislator, a member of the United States House of Representatives, and twice an unsuccessful candidate for election to the U.S. Senate. As an outspoken opponent of the expansion of slavery in the United States, Lincoln won the Republican Party nomination in 1860 and was elected president later that year. His tenure in office was occupied primarily with the defeat of the secessionist Confederate States of America in the American Civil War. He introduced measures that resulted in the abolition of slavery, issuing his Emancipation Proclamationin 1863 and promoting the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution. Six days after the large-scale surrender of Confederate forces under General Robert E. Lee, Lincoln became the first American president to be assassinated. Lincoln had closely supervised the victorious war effort, especially the selection of top generals, including Ulysses S. Grant.

Lincoln successfully defused the Trent affair, a war scare with Britain late in 1861. Under his leadership, the Union took control of the border slave states at the start of the war. Additionally, he managed his own reelection in the 1864 presidential election. Lincoln successfully rallied public opinion through his rhetoric and

speeches; his Gettysburg Address (1863) became an iconic symbol of the nation's duty. At the close of the war, Lincoln held a moderate view of Reconstruction, seeking to speedily reunite the nation through a policy of generous reconciliation. Lincoln has consistently been ranked by scholars as one of the greatest of all U.S. Presidents. Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, to Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks, two farmers, in a one-room log cabin on the 348-acre (1.4 km2) Sinking Spring Farm, in southeast Hardin County, Kentucky (now part of LaRue County), making him the first president born in the west. Lincoln was not given a middle name. His ancestor Samuel Lincoln had arrived in Hingham, Massachusetts from England in the 17th century. His grandfather, also named Abraham Lincoln, had moved to Kentucky, where he owned over 5,000 acres (20 km2), and was ambushed and killed by an Indian raid in 1786. Thomas

Lincoln was a respected citizen of rural Kentucky. He owned several

farms, including the Sinking Spring Farm, although he was not wealthy.

The family belonged to a Separate Baptists church,

which had high moral standards frowning on alcohol consumption and

dancing, and many church members were opposed to slavery. Abraham himself never joined their church, or any other church. In

1816, the Lincoln family left Kentucky to avoid the expense of fighting

for one of their properties in court, and made a new start in Perry County, Indiana (now in Spencer County).

Lincoln later noted that this move was "partly on account of slavery",

and partly because of difficulties with land deeds in Kentucky.

Abraham's father disapproved of slavery on religious grounds and

because it was hard to compete economically with farms operated by

slaves. Unlike land in the Northwest Territory, Kentucky never had a proper U.S. survey, and farmers often had difficulties proving title to their property. When Lincoln was nine, his mother, then 34 years old, died of milk sickness. Soon afterwards, his father remarried to Sarah Bush Johnston.

Lincoln and his stepmother were close; he called her "Mother" for the

rest of his life, but he became increasingly distant from his father. In 1830, fearing a milk sickness outbreak, the family settled on public land in Macon County, Illinois. The next year, when his father relocated the family to a new homestead in Coles County, Illinois, 22-year-old Lincoln struck out on his own, canoeing down the Sangamon River to the village of New Salem in Sangamon County. Later that year, hired by New Salem businessman Denton Offutt and accompanied by friends, he took goods from New Salem to New Orleans via flatboat on the Sangamon, Illinois and Mississippi rivers. Lincoln's

formal education consisted of about 18 months of schooling, but he was

largely self-educated and an avid reader. He was also skilled with an

axe and a talented local wrestler, the latter of which helped give him

confidence. Lincoln avoided hunting and fishing because he did not like killing animals, even for food. Lincoln's first love was Ann Rutledge.

He met her when he first moved to New Salem, and by 1835 they had

reached a romantic understanding. Rutledge, however, died on August 25,

probably of typhoid fever. Earlier,

in either 1833 or 1834, he had met Mary Owens, the sister of his friend

Elizabeth Abell, when she was visiting from her home in Kentucky. Late

in 1836, Lincoln agreed to a match proposed by Elizabeth between him

and her sister, if Mary ever returned to New Salem. Mary did return in

November 1836 and Lincoln courted her for a time; however they both had

second thoughts about their relationship. On August 16, 1837, Lincoln

wrote Mary a letter from Springfield, to which he had moved that April

to begin his law practice, suggesting he would not blame her if she

ended the relationship. She never replied, and the courtship was over. In 1840, Lincoln became engaged to Mary Todd, from a wealthy slave holding family based in Lexington, Kentucky. They met in Springfield in December 1839, and were engaged sometime around that Christmas. A

wedding was set for January 1, 1841, but the couple split as the

wedding approached. They later met at a party, and then married on

November 4, 1842, in the Springfield mansion of Mary's married sister. In 1844, the couple bought a house on Eighth and Jackson in Springfield, near Lincoln's law office. The Lincolns soon had a budding family, with the birth of son Robert Todd Lincoln in Springfield, Illinois on August 1, 1843, and second son Edward Baker Lincoln on March 10, 1846, also in Springfield. Robert,

however, would be the only one of the Lincolns' children to survive

into adulthood. Edward Lincoln died on February 1, 1850 in Springfield,

likely of tuberculosis. The Lincolns' grief over this loss was somewhat assuaged by the birth of William "Willie" Wallace Lincoln nearly eleven months later, on December 21. But Willie himself died of a fever at the age of eleven on February 20, 1862, in Washington, D.C., during President Lincoln's first term. The Lincolns' fourth son Thomas "Tad" Lincoln was born on April 4, 1853, and, although he outlived his father, died at the age of eighteen on July 16, 1871 in Chicago. Robert Lincoln eventually went on to attend Phillips Exeter Academy and Harvard College. His (and by extension, his father's) last known lineal descendant, Robert Todd Lincoln Beckwith, died December 24, 1985. The

death of the Lincolns' sons had profound effects on both Abraham and

Mary. Later in life, Mary Todd Lincoln found herself unable to cope

with the stresses of losing her husband and sons, and this eventually led Robert Lincoln to involuntarily commit her to a mental health asylum in 1875. Abraham

Lincoln himself was contemporaneously described as suffering from

"melancholy" throughout his legal and political life, a condition which

modern mental health professionals would now typically characterize as clinical depression. Lincoln began his political career in March 1832 at age 23 when he announced his candidacy for the Illinois General Assembly.

He made the decision based on self-confidence; he felt himself equal to

any man. He was esteemed by the residents of New Salem, but he didn't

have an education, powerful friends, or money. The centerpiece of his

platform was the undertaking of navigational improvements on the Sangamon River. Before the election he served as a captain in a company of the Illinois militia during the Black Hawk War,

although he never saw combat. Lincoln returned from the militia after a

few months and was able to campaign throughout the county before the

August 6 election. When the votes were

counted, Lincoln finished eighth out of thirteen candidates (only the

top four were elected), but he did manage to secure 277 out of the 300

votes cast in the New Salem precinct. In 1834, he won an election to the state legislature. He was labeled a Whig, but ran a bipartisan campaign. He then decided to become a lawyer, and began teaching himself law by reading Commentaries on the Laws of England. Admitted to the bar in 1837, he moved to Springfield, Illinois, that April, and began to practice law with John T. Stuart, Mary Todd's cousin, who let Lincoln have the run of his law library while studying to be a lawyer. With

a reputation as a formidable adversary during cross-examinations and

closing arguments, Lincoln became an able and successful lawyer. In

1841, Lincoln entered law practice with William Herndon, whom Lincoln thought "a studious young man". He served four successive terms in the Illinois House of Representatives as a representative from Sangamon County, affiliated with the Whig party. In 1837, he and another legislator declared that slavery was "founded on both injustice and bad policy" the first time he had publicly opposed slavery. Lincoln was a Whig, and since the early 1830s had strongly admired the policies and leadership of Henry Clay. The party favored economic expansion such as improving roads and increasing trade. In 1846, Lincoln was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, where he served one two-year term. As a House member, Lincoln was a dedicated Whig, showing up for most votes and giving speeches that echoed the party line. He used his office as an opportunity to speak out against the Mexican–American War, which he attributed to President Polk's desire for "military glory. Despite his admiration for Henry Clay, Lincoln was a key early supporter of Zachary Taylor's candidacy for the 1848 presidential election. When Lincoln's term ended, the incoming Taylor administration offered him the governorship of the Oregon Territory.

The territory leaned heavily Democratic, and Lincoln doubted they would

elect him as governor or as a senator after they were admitted to the

union, so he returned to Springfield. Back

in Springfield, Lincoln turned most of his energies to making a living

practicing law, handling "every kind of business that could come before

a prairie lawyer." His reputation grew and he appeared before the Supreme Court of the United States, arguing a case involving a canal boat that sank after hitting a bridge. Lincoln represented numerous transportation interests, such as the river barges and

the railroads. As a riverboat man, Lincoln had initially favored

riverboat interests, but ultimately he represented whoever hired him. Lincoln

appeared in front the of the Illinois Supreme Court 175 times, 51 times

as sole counsel, of which, 31 were decided in his favor. Lincoln's most notable criminal trial came in 1858 when he defended William "Duff" Armstrong, who was on trial for the murder of James Preston Metzker. The case is famous for Lincoln's use of judicial notice to

show an eyewitness had lied on the stand. After the witness testified

to having seen the crime in the moonlight, Lincoln produced a Farmers' Almanac to

show that the moon on that date was at such a low angle it could not

have produced enough illumination to see anything clearly. Based on

this evidence, Armstrong was acquitted. Lincoln returned to politics in response to the Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854), which expressly repealed the limits on slavery's extent as established by the Missouri Compromise (1820). Illinois Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, the most powerful man in the Senate, proposed popular sovereignty as

the solution to the slavery impasse, and incorporated it into the

Kansas–Nebraska Act. Douglas argued that in a democracy the people

should have the right to decide whether to allow slavery in their

territory, rather than have such a decision imposed on them by the

national Congress. In the October 16, 1854, "Peoria Speech", Lincoln outlined his position on slavery that he would repeat over the next six years on the route to the presidency. In late 1854, Lincoln decided to run for the United States Senate as a Whig. Despite leading in the first six rounds of voting in the state legislature, Lincoln instructed his backers to vote for Lyman Trumbull to prevent pro-Nebraska candidate Joel Aldrich Matteson from winning. Trumbull beat Matteson in the tenth round of voting. The

Whigs had been irreparably split by the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Drawing on remnants of the old Whig party, and on

disenchanted Free Soil, Liberty, and Democratic party members, he was

instrumental in forging the shape of the new Republican Party. At the Republican convention in 1856, Lincoln placed second in the contest to become the party's candidate for Vice-President. In 1857–58, Douglas broke with President Buchanan,

leading to a fight for control of the Democratic Party. Some eastern

Republicans even favored the reelection of Douglas in 1858, since he

had led the opposition to the Lecompton Constitution, which would have admitted Kansas as a slave state. Accepting the Republican nomination for Senate in 1858, Lincoln delivered his famous speech: "'A house divided against itself cannot stand.'

I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half

free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved — I do not expect the

house to fall — but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will

become all one thing, or all the other." The

speech created an evocative image of the danger of disunion caused by

the slavery debate, and rallied Republicans across the north. The

1858 campaign featured the Lincoln–Douglas debates, generally

considered the most famous political debate in American history. Though

the Republican legislative candidates won more popular votes, the

Democrats won more seats, and the legislature reelected Douglas to the

Senate.Nevertheless, Lincoln's speeches on the issue transformed him into a national political figure. On February 27, 1860, New York party leaders invited Lincoln to give a speech at Cooper Union to

group of powerful Republicans. In one of the most important speeches of

his career, Lincoln showed that he was a contender for the Republican's

presidential nomination. On May 9–10, 1860, the Illinois Republican State Convention was held in Decatur. At this convention, Lincoln received his first endorsement to run for the presidency. On May 18, at the 1860 Republican National Convention in Chicago,

Lincoln emerged as the Republican candidate on the third ballot.

Meanwhile, Douglas was selected as the candidate of the northern

Democrats, with Herschel Vespasian Johnson as

the vice-presidential candidate. Delegates from eleven slave states

walked out of the Democrat's convention, disagreeing with Douglas's

position on Popular sovereignty, and ultimately selected John C. Breckinridge as their candidate. As

Douglas stumped the country, Lincoln was the only one of the four major

candidates to give no speeches whatever. Instead he monitored the

campaign closely but relied on the enthusiasm of the Republican Party.

On November 6, 1860, Lincoln was elected as the 16th President of the United States, beating Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, John C. Breckinridge of the Southern Democrats, and John Bell of the new Constitutional Union Party.

He was the first Republican president, winning entirely on the strength

of his support in the North: he was not even on the ballot in ten

states in the South, and won only two of 996 counties in all the

Southern states. With the emergence of the Republicans as the nation's first major sectional party by the mid-1850s, the old Second Party System collapsed and a realignment created the Third Party System. It became the stage on which sectional tensions were

played out. Although little of the West–the focal point of sectional

tensions– was fit for cotton cultivation, Southern secessionists read

the political fallout as a sign that their power in national politics

was rapidly weakening. As Lincoln's election became more likely, secessionists made clear their intent to leave the Union. On December 20, 1860, South Carolina took the lead; by February 1, 1861, Florida, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas had followed. The seven states soon declared themselves to be a new nation, the Confederate States of America. The

upper South (Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee,

Kentucky, Missouri, and Arkansas) listened to, but initially rejected,

the secessionist appeal. President Buchanan and President-elect Lincoln refused to recognize the Confederacy. Attempts at compromise, such as the Crittenden Compromise which would have extended the Missouri line of 1820, were discussed. The Confederate States of America selected Jefferson Davis on February 9, 1861, as their provisional President. President-elect Lincoln evaded possible assassins in Baltimore, and on February 23, 1861, arrived in disguise in Washington, D.C. At

his inauguration on March 4, 1861, sharpshooters watched the inaugural

platform, while soldiers on horseback patrolled the surrounding area. In his first inaugural address,

Lincoln declared, "I hold that in contemplation of universal law and of

the Constitution the Union of these States is perpetual. Perpetuity is

implied, if not expressed, in the fundamental law of all national

governments." Also in his inaugural address, in a final attempt

to reunite the states and prevent certain war, Lincoln supported the

pending Corwin Amendment to

the Constitution, which had passed Congress the previous day. This

amendment, which explicitly protected slavery in those states in which

it already existed, was considered by Lincoln to be a possible way to

stave off secession. By the time Lincoln took office, the Confederacy was an established fact, and no leaders of the insurrection proposed rejoining the Union on any terms. Believing that a peaceful solution

was still possible, Lincoln decided to not take any action against the

South unless the Unionists themselves were attacked first. This finally happened in April 1861. On April 12, 1861, Union troops at Fort Sumter were fired upon and forced to surrender. On April 15, Lincoln called on the states to send detachments totaling 75,000 troops, to

recapture forts, protect the capital, and "preserve the Union", which

in his view still existed intact despite the actions of the seceding

states. These events forced the states to choose sides. Virginia declared its secession, after which the Confederate capital was moved from Montgomery to Richmond. North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas also voted for secession over the next two months. Missouri, Kentucky and Maryland threatened secession, but neither they nor the slave state of Delaware seceded. Lincoln urgently negotiated with state leaders there, promising not to interfere with slavery. The

war was a source of constant frustration for the president and occupied

nearly all of his time. He had a contentious relationship with General McClellan, who became general-in-chief of all the Union armies in the wake of the embarrassing Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run and after the retirement of Winfield Scott in late 1861.Despite

his inexperience in military affairs, Lincoln immediately took an

active part in determining war strategy. His priorities were twofold:

to ensure that Washington was

well defended; and to conduct an aggressive war effort that would

satisfy the demand in the North for prompt, decisive victory. McClellan, a youthful West Point graduate and railroad executive called back to active military service, took a more cautious approach. He took several months to plan and execute his Peninsula Campaign, with the objective of capturing Richmond by moving the Army of the Potomac by boat to the peninsula and

then traveling by land to Richmond. McClellan's delay concerned

Lincoln, as did his insistence that no troops were needed to defend

Washington, Lincoln insisted on holding some of McClellan's troops to

defend the capital, a decision McClellan blamed for the ultimate

failure of the Peninsula Campaign. McClellan, a conservative Democrat, was passed over for general-in-chief (that is, chief strategist) in favor of Henry Wager Halleck, after giving Lincoln hi sHarrison's Landing Letter, where he offered unsolicited political advice to Lincoln urging caution in the war effort. McClellan's letter incensed Radical Republicans, who successfully pressured Lincoln to appoint John Pope, a Republican, as head of the new Army of Virginia.

Pope complied with Lincoln's strategic desire to move toward Richmond

from the north, thus protecting the capital from attack. However, Pope

was soundly defeated at the Second Battle of Bull Run in the summer of 1862, forcing the Army of the Potomac to defend Washington for a second time. In response to his failure, Pope was sent to Minnesota to fight the Sioux. Despite

his dissatisfaction with McClellan's failure to reinforce Pope, Lincoln

restored him to command of all forces around Washington, to the dismay

of his cabinet (all save Seward), who wished McClellan gone. Two days after McClellan's return to command, General Lee's forces crossed the Potomac River into Maryland, leading to the Battle of Antietam (September 1862). The

ensuing Union victory, one of the bloodiest in American history,

enabled Lincoln to give notice that he would issue an Emancipation

Proclamation in January, but he relieved McClellan of his command after waiting for the conclusion of the 1862 midterm elections and appointed Republican Ambrose Burnside to head the Army of the Potomac. Burnside was politically neutral, which Lincoln desired, and for the most part supported the President's aims. Burnside

had promised to follow through on Lincoln's strategic vision for a

strong offensive against Lee and Richmond. After Burnside was

stunningly defeated at Fredericksburg in December, Joseph Hooker took command, despite his history of "loose talk" and criticizing former commanders. Hooker was routed by Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in May, 1863, but

continued to command his troops for roughly two months. Hooker did not

agree with Lincoln's desire to divide his troops, and possibly force

Lee to do the same, and tendered his resignation, which was accepted.

During the Gettysburg Campaign he was replaced by George Meade. Using

black troops and former slaves was official government policy after the

issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation. At first Lincoln was

reluctant to fully implement this program, but by the spring of 1863 he

was ready to initiate "a massive recruitment of Negro troops." In a

letter to Andrew Johnson, the military governor of Tennessee,

encouraging him to lead the way in raising black troops, Lincoln wrote,

"The bare sight of fifty thousand armed, and drilled black soldiers on

the banks of the Mississippi would end the rebellion at once." By

the end of 1863, at Lincoln's direction, General Lorenzo Thomas had

recruited twenty regiments of African Americans from the Mississippi

Valley. After

the Union victory at Gettysburg, Meade's failure to pursue Lee and

months of inactivity for the Army of the Potomac persuaded Lincoln that

a change was needed. McClellan was seeking the Democratic nomination

for President, and Lincoln worried that Grant might also have political

aspirations. Lincoln convinced himself that Grant didn't have political

aspirations, in the immediate at least, and made Ulysses S. Grant commander of the Union Army. Grant already had a solid string of victories in the Western Theater, including the battles of Vicksburg and Chattanooga. Responding to criticism of Grant, Lincoln replied, "I can't spare this man. He fights." Grant waged his bloody Overland Campaign in 1864 with a strategy of a war of attrition, characterized by high Union losses at battles such as the Wilderness and Cold Harbor, but by proportionately higher Confederate losses. The

high casualty figures alarmed the nation, and, after Grant lost a third

of his army, Lincoln asked what Grant's plans were. "I propose to fight

it out on this line if it takes all summer," replied Grant. Lincoln and

the Republican party mobilized support throughout the North, backed

Grant to the hilt, and replaced his losses. The Confederacy was out of replacements, so Lee's army shrank with every battle, forcing it back to trenches outside Petersburg. In April 1865, Lee's army finally crumbled under Grant's pounding, and Richmond fell. Lincoln

authorized Grant to target the Confederate infrastructure – such as

plantations, railroads, and bridges – hoping to destroy the South's

morale and weaken its economic ability to continue fighting. This

strategy allowed Generals Sherman and Sheridan to destroy plantations and towns in the Shenandoah Valley, Georgia, and South Carolina. The damage caused by Sherman's March to the Seathrough Georgia totaled more than $100 million by Sherman's own estimate. Lincoln

maintained that the powers of his administration to end slavery were

limited by the Constitution. He expected to cause the eventual

extinction of slavery by stopping its further expansion into any U.S.

territory, and by persuading states to accept compensated emancipation if

the state would outlaw slavery (an offer that took effect only in

Washington, D.C.). In July 1862, Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act,

which freed the slaves of anyone convicted of aiding the rebellion.

Although Lincoln believed it wasn't in Congress's remit to free any

slaves, he approved the bill. He felt freeing the slaves could only be

done by the Commander in Chief during wartime, and that signing the

bill would help placate those in Congress who wanted to do it through

legislation. In that month, Lincoln discussed a draft of the

Emancipation Proclamation with his cabinet. In it, he stated that "as a

fit and necessary military measure" on January 1, 1863, "all persons held as a slaves" in

the Confederate states will " thenceforward, and forever, be free." The Emancipation Proclamation,

announced on September 22, 1862 and put into effect on January 1, 1863,

freed slaves in territories not already under Union control. As Union

armies advanced south, more slaves were liberated until all of them in

Confederate territory (over three million) were freed. Lincoln later

said: "I never, in my life, felt more certain that I was doing right,

than I do in signing this paper." The proclamation made the abolition

of slavery in the rebel states an official war goal. Lincoln then threw

his energies into passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to permanently

abolish slavery throughout the nation. He

personally lobbied individual Congressmen for the Amendment, which was

passed by the Congress in early 1865, shortly before his death. A few days after the Emancipation was announced, thirteen Republican governors met at the War Governors' Conference; they supported the president's Proclamation, but suggested the removal of General George B. McClellan as commander of the Union's Army of the Potomac. For some time, Lincoln continued earlier plans to set up colonies for

the newly freed slaves. He commented favorably on colonization in the

Emancipation Proclamation, but all attempts at such a massive

undertaking failed. Although the Battle of Gettysburg was

a Union victory, it was also the bloodiest battle of the war and dealt

a blow to Lincoln's war effort. As the Union Army decreased in numbers

due to casualties, more soldiers were needed to replace the ranks.

Lincoln's 1863 military drafts were considered "odious" among many in

the north, particularly immigrants. The New York Draft Riots of July 1863 were the most notable manifestation of this discontent. Writing to Lincoln in September 1863, the Governor of Pennsylvania, Andrew Gregg Curtin, warned that political sentiments were turning against Lincoln and the war effort. Therefore,

in the fall of 1863, Lincoln's principal aim was to sustain public

support for the war effort. This goal became the focus of his address

at the Gettysburg battlefield cemetery on November 19. The Gettysburg Address is one of the most quoted speeches in United States history. After Union victories at Gettysburg, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga in 1863, overall victory seemed at hand, and Lincoln promoted Ulysses S. Grant General-in-Chief

on March 12, 1864. When the spring campaigns turned into bloody

stalemates, Lincoln supported Grant's strategy of wearing down Lee's Confederate

army at the cost of heavy Union casualties. With an election looming,

he easily defeated efforts to deny his renomination. At the Convention,

the Republican Party selected Andrew Johnson, a War Democrat from the Southern state of Tennessee, as his running mate to form a broader coalition. They ran on the new Union Party ticket uniting Republicans and War Democrats. Nevertheless,

Republicans across the country feared that Lincoln would be defeated.

Acknowledging this fear, Lincoln wrote and signed a pledge that, if he

should lose the election, he would still defeat the Confederacy before

turning over the White House: Lincoln

did not show the pledge to his cabinet, but asked them to sign the

sealed envelope. While the Democratic platform followed the Peace wing of the party and called the war a "failure," their candidate, General George B. McClellan,

supported the war and repudiated the platform. Lincoln provided Grant

with new replacements and mobilized his party to support Grant and win

local support for the war effort. Sherman's capture of Atlanta in

September ended defeatist jitters; the Democratic Party was deeply

split, with some leaders and most soldiers openly for Lincoln; the

Union party was united and energized, and Lincoln was easily reelected

in a landslide. He won all but three states, including 78% of the Union

soldiers' vote. On March 4, 1865, Lincoln delivered his second inaugural address,

his favorite of all his speeches.

Originally, John Wilkes Booth, a well-known actor and a Confederate spy from Maryland, had formulated a plan to kidnap Lincoln

in exchange for the release of Confederate prisoners. After attending

an April 11 speech in which Lincoln promoted voting rights for blacks,

an incensed Booth changed his plans and determined to assassinate the

president. Learning that the President and First Lady would be attending Ford's Theatre, he laid his plans, assigning his co-conspirators to assassinate Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William H. Seward. Without his main bodyguard Ward Hill Lamon, to whom he related his famous dream regarding his own assassination, Lincoln left to attend the play Our American Cousin on

April 14, 1865. As a lone bodyguard wandered, and Lincoln sat in his

state box (Box 7) in the balcony, Booth crept up behind the President

and waited for what he thought would be the funniest line of the play

("You sock-dologizing old man-trap"), hoping the laughter would muffle

the noise of the gunshot. When the laughter began, Booth jumped into

the box and aimed a single-shot, round-slug 0.44 caliber Deringer at

his head, firing at point-blank range. Major Henry Rathbone momentarily grappled with Booth but was cut by Booth's knife. Booth then leaped to the stage and shouted "Sic semper tyrannis!" (Latin: Thus always to tyrants) and escaped, despite a broken leg suffered in the leap. A twelve-day manhunt ensued, in which Booth was chased by Federal agents (under the direction of Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton). He was eventually cornered in a Virginia barn house and shot, dying of his wounds soon after. An army surgeon, Doctor Charles Leale, initially assessed Lincoln's wound as mortal. The President was taken across the street from the theater to the Petersen House, where he lay in a coma for nine hours before dying. Several physicians attended Lincoln, including U.S. Army Surgeon General Joseph K. Barnes of the Army Medical Museum.

Using a probe, Barnes located some fragments of Lincoln's skull and the

ball lodged 6 inches (15 cm) inside his brain. Lincoln never

regained consciousness and was pronounced dead at 7:22:10 a.m. April

15, 1865. He was the first president to be assassinated or to lie in state. Lincoln's body was carried by train in a grand funeral procession through several states on its way back to Illinois. While much of the nation mourned him as the savior of the United States, Copperheads celebrated the death of a man they considered a tyrant. The Lincoln Tomb in

Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield, is 177 feet (54 m) tall

and, by 1874, was surmounted with several bronze statues of Lincoln. To

prevent repeated attempts to steal Lincoln's body and hold it for

ransom, Robert Todd Lincoln had it exhumed and reinterred in concrete several feet thick in 1901.

Reconstruction

began during the war as Lincoln and his associates pondered questions

of how to reintegrate the Southern states and what to do with

Confederate leaders and the freed slaves. Lincoln led the "moderates"

regarding Reconstruction policy, and was usually opposed by the Radical

Republicans, under Thaddeus Stevens in the House and Charles Sumner and Benjamin Wade in

the Senate (though he cooperated with these men on most other issues).

Determined to find a course that would reunite the nation and not

alienate the South, Lincoln urged that speedy elections under generous

terms be held throughout the war in areas behind Union lines. His Amnesty Proclamation of

December 8, 1863, offered pardons to those who had not held a

Confederate civil office, had not mistreated Union prisoners, and would

sign an oath of allegiance. Critical decisions had to be made as state after state was reconquered. Of special importance were Tennessee, where Lincoln appointed Andrew Johnson as governor, and Louisiana,

where Lincoln attempted a plan that would restore statehood when 10% of

the voters agreed to it. The Radicals thought this policy too lenient,

and passed their own plan, the Wade-Davis Bill, in 1864. When Lincoln pocket vetoed the bill, the Radicals retaliated by refusing to seat representatives elected from Louisiana, Arkansas, and Tennessee. Near

the end of the war, Lincoln made an extended visit to Grant's

headquarters at City Point, Virginia. This allowed the president to

confer in person with Grant and Sherman about ending hostilities (as

Sherman managed a hasty visit to Grant from his forces in North

Carolina at the same time). Lincoln also was able to visit Richmond after it was taken by the Union forces and to make a public gesture of sitting at Jefferson Davis' own

desk, symbolically saying to the nation that the President of the

United States held authority over the entire land. He was greeted at

the city as a conquering hero by freed slaves. Lincoln arrived back in Washington on the evening of April 9, 1865, the day Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House in

Virginia. The war was effectively over. The other rebel armies

surrendered soon after, and there was no subsequent guerrilla warfare.

Lincoln's rhetoric defined the issues of the war for the nation, the world, and posterity. Lincoln

believed in the Whig theory of the presidency, which left Congress to

write the laws while he signed them; Lincoln exercised his veto power only four times, the only significant instance being his pocket veto of the Wade-Davis Bill. Other

important legislation involved two measures to raise revenues for the

Federal government: tariffs (a policy with long precedent), and a

Federal income tax (which was new). Lincoln

also presided over the expansion of the federal government's economic

influence in several other areas. The creation of the system of

national banks by the National Banking Acts of

1863, 1864, and 1865 allowed the creation of a strong national

financial system. In 1862, Congress created, with Lincoln's approval,

the Department of Agriculture, although that institution would not become a Cabinet-level department until 1889. The Legal Tender Act of 1862 established the United States Note, the first paper currency in United States history since the Continentals that were issued during the Revolution. This was done to increase the money supply to pay for fighting the war. In 1862, Lincoln sent a senior general, John Pope, to put down the "Sioux Uprising" in Minnesota. Presented with 303 death warrants for convicted Santee Dakota who

were accused of killing innocent farmers, Lincoln ordered a personal

review of these warrants, eventually approving 39 of these for execution. Abraham Lincoln is largely responsible for the institution of the Thanksgiving holiday in

the United States.