<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, 1788

- Composer Frédéric François Chopin, 1810

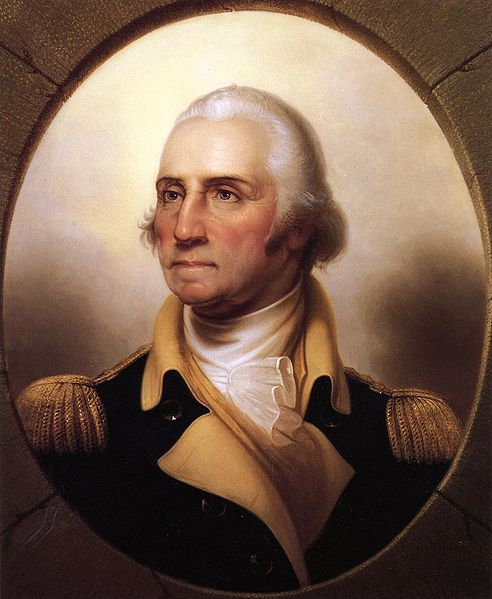

- First President of the United States George Washington, 1732

George Washington (February 22, 1732 [O.S. February 11, 1731] – December 14, 1799) was the commander of the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) and the first President of the United States of America (1789–1797). For his central role in the formation of the United States, he is often referred to as "the father of his country".

The Continental Congress appointed Washington commander-in-chief of the American revolutionary forces in 1775. The following year, he forced the British out of Boston, lost New York City, and crossed the Delaware River in New Jersey, defeating the surprised enemy units later that year. As a result of his strategy, Revolutionary forces captured the two main British combat armies at Saratoga and Yorktown. Negotiating with Congress, the colonial states, and French allies,

he held together a tenuous army and a fragile nation amid the threats

of disintegration and failure. Following the end of the war in 1783, King George III asked

what Washington would do next and was told of rumors that he'd return

to his farm; this prompted the king to state, "If he does that, he will

be the greatest man in the world." Washington did return to private

life and retired to his plantation at Mount Vernon. He presided over the Philadelphia Convention that drafted the United States Constitution in 1787 because of general dissatisfaction with the Articles of Confederation. Washington became President of the United States in 1789 and established many of the customs and usages of the new government's executive

department. He sought to create a nation capable of surviving in a

world torn asunder by war between Britain and France. His unilateral Proclamation of Neutrality of 1793 provided a basis for avoiding any involvement in foreign conflicts. He supported plans to build a strong central government by funding the national debt, implementing an effective tax system, and creating a national bank. Washington avoided the temptation of war and a decade of peace with Britain began with the Jay Treaty in 1795; he used his prestige to get it ratified over intense opposition from the Jeffersonians. Although never officially joining the Federalist Party, he supported its programs and was its inspirational leader. Washington's farewell address was

a primer on republican virtue and a stern warning against partisanship,

sectionalism, and involvement in foreign wars. Washington was awarded

the very first Congressional Gold Medal with the Thanks of Congress. Washington died in 1799, and the funeral oration delivered by Henry Lee stated that of all Americans, he was "first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen". George Washington was born on February 22, 1732 [O.S. February 11, 1731] the first child of Augustine Washington and his second wife, Mary Ball Washington, on their Pope's Creek Estate near present-day Colonial Beach in Westmoreland County, Virginia.

His father had four children by his first wife.

Moving to Ferry Farm in Stafford County at age six, George was educated in the home by his father and eldest brother. Washington's ancestors were from Sulgrave, England; his great-grandfather, John Washington, immigrated to Virginia in 1657. The

growth of tobacco as a commodity in Virginia could be measured by the

number of slaves imported to cultivate it. When Washington was born,

the population of the colony was 50 percent black, mostly enslaved Africans and African Americans. In his youth, Washington worked as a surveyor, and acquired what would become invaluable knowledge of the terrain around his native Colony of Virginia. His eldest brother's marriage into the powerful Fairfax family gained young George the patronage of Thomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron, the Proprietor of the Northern Neck, which encompassed some five million acres. In late July 1749, immediately following the establishment of the town of Alexandria, Virginia along the Potomac River, 17-year old George was commissioned as the first Surveyor of the newly created Culpeper County, Virginia in

the interior of the colony. This appointment was undoubtedly secured at

the behest of Lord Fairfax and his cousin (and resident land agent)

William Fairfax of Belvoir, who sat on the Governor's Council. Washington

embarked upon a career as a planter, which historians defined as those

who held 20 or more slaves. In 1748 he was invited to help survey Lord Fairfax's lands west of the Blue Ridge. In 1749, he was appointed to his first public office, surveyor of newly created Culpeper County. Through his half-brother, Lawrence Washington, he became interested in the Ohio Company, which aimed to exploit Western lands. In 1751, George and his half-brother traveled to Barbados, staying at Bush Hill House, hoping for an improvement in Lawrence's tuberculosis. This was the only time George Washington traveled outside what is now the United States. After Lawrence's death in 1752, George inherited part of his estate and took over some of Lawrence's duties as adjutant of the colony. In late 1752, Virginia's newly arrived Governor, Robert Dinwiddie,

divided command of the militia into four regions and George applied for

one of the commands, his only qualifications being his zeal and being

the younger brother of the former adjutant. Washington was appointed a

district adjutant general in the Virginia militia in 1752, which appointed him Major Washington at the age of 20. He was charged with training the militia in the quarter assigned to him. At age 21, in Fredericksburg, Washington became a Master Mason in the organization of Freemasons, a fraternal organization that was a lifelong influence. In December 1753, Washington was asked by Governor Dinwiddie to carry a British ultimatum to the French Canadians on the Ohio frontier. Washington assessed French military strength and intentions, and delivered the message to the French Canadians at Fort Le Boeuf in present day Waterford, Pennsylvania.

The message, which went unheeded, called for the French Canadians to

abandon their development of the Ohio country. In 1754, Dinwiddie commissioned Washington a Lieutenant Colonel and ordered him to lead an expedition to Fort Duquesne to drive out the French Canadians. With his American Indian allies led by Tanacharison, Washington and his troops ambushed a French Canadian scouting party of some 30 men, led by Joseph Coulon de Jumonville. Washington and his troops were subsequently overwhelmed at Fort Necessity by

a larger and better positioned French Canadian and Indian force, in

what was Washington's only military surrender. The terms of surrender

included a statement that Washington had assassinated Jumonville after

the ambush. Washington could not read French, and, unaware of what it

said, signed his name. Released

by the French Canadians, Washington returned to Virginia, where he was

cleared of blame for the defeat, but resigned because he did not like

the new arrangement of the Virginia Militia. In 1755, Washington was an aide to British General Edward Braddock on the ill-fated Monongahela expedition. This

was a major effort to retake the Ohio Country. While Braddock was

killed and the expedition ended in disaster, Washington distinguished

himself as the Hero of the Monongahela. Subsequent

to this action, Washington was given a difficult frontier command in

the Virginia mountains, and was rewarded by being promoted to colonel and named commander of all Virginia forces. In 1758, Washington participated as a Brigadier General in the Forbes expedition that prompted French evacuation of Fort Duquesne, and British establishment of Pittsburgh. Later

that year, Washington resigned from active military service and spent

the next sixteen years as a Virginia planter and politician. On January 6, 1759, Washington married the widow Martha Dandridge Custis. Surviving letters suggest that he may have been in love at the time with Sally Fairfax,

the wife of a friend. Some historians believe George and Martha were

distantly related. Nevertheless, George and Martha made a good

marriage, and together raised her two children from her previous

marriage. George and Martha never had any children together—his earlier

bout with smallpox followed, possibly, by tuberculosis may have made him sterile. The newlywed couple moved to Mount Vernon, where he took up the life of a planter and political figure. Washington

lived an aristocratic lifestyle—fox hunting was a favorite leisure

activity. Like most Virginia planters, he imported luxuries and other

goods from England and paid for them by exporting his tobacco crop.

Extravagant spending and the unpredictability of the tobacco market

meant that many Virginia planters of Washington's day were losing

money. (Thomas Jefferson, for example, would die deeply in debt.) Washington

began to pull himself out of debt by diversification. By 1766, he had

switched Mount Vernon's primary cash crop from tobacco to wheat, a crop

which could be sold in America, and diversified operations to include

flour milling, fishing, horse breeding, spinning, and weaving. During

these years, Washington concentrated on his business activities and

remained somewhat aloof from politics. Although he expressed opposition

to the 1765 Stamp Act,

the first direct tax on the colonies, he did not take a leading role in

the growing colonial resistance until after protests of the Townshend Acts (enacted in 1767) had become widespread. In May 1769, Washington introduced a proposal drafted by his friend George Mason,

which called for Virginia to boycott English goods until the Acts were

repealed. Parliament repealed the Townshend Acts in 1770, and, for

Washington at least, the crisis had passed. However, Washington

regarded the passage of the Intolerable Acts in 1774 as "an Invasion of our Rights and Privileges". In July 1774, he chaired the meeting at which the "Fairfax Resolves" were adopted, which called for, among other things, the convening of a Continental Congress. In August, Washington attended the First Virginia Convention, where he was selected as a delegate to the First Continental Congress. After fighting broke out in April 1775, Washington appeared at the Second Continental Congress in

military uniform, signaling that he was prepared for war. Washington

had the prestige, the military experience, the charisma and military

bearing, the reputation of being a strong patriot, and he was supported

by the South, especially Virginia. Although he did not explicitly seek

the office of commander and even claimed that he was not equal to it,

there was no serious competition. Congress created the Continental Army on June 14, 1775. Nominated by John Adams of Massachusetts, Washington was then appointed Major General and elected by Congress to be Commander-in-chief. Washington assumed command of the Continental Army in the field at Cambridge, Massachusettsin July 1775, during the ongoing siege of Boston.

Realizing his army's desperate shortage of gunpowder, Washington asked

for new sources. British arsenals were raided (including some in the Caribbean)

and some manufacturing was attempted; a barely adequate supply (about

2.5 million pounds) was obtained by the end of 1776, mostly from France. Washington reorganized the army during the long standoff, and forced the British to withdraw by putting artillery on Dorchester Heights overlooking the city. The British evacuated Boston and Washington moved his army to New York City. In August 1776, British General William Howe launched

a massive naval and land campaign designed to seize New York and offer

a negotiated settlement. The Continental Army under Washington engaged

the enemy for the first time as an army of the newly declared

independent United States at the Battle of Long Island, the largest battle of the entire war. His army's subsequent nighttime retreat across the East River without the loss of a single life or materiel has been seen by some historians as one of Washington's greatest military feats. This and several other British victories sent Washington scrambling out of New York and across New Jersey, which left the future of the Continental Army in doubt. On the night of December 25, 1776, Washington staged a counterattack, leading the American forces across the Delaware River to capture nearly 1,000 Hessians in Trenton, New Jersey. Washington followed up his victory at Trenton with another one at Princeton in

early January. British forces defeated Washington's troops in the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777. Howe outmaneuvered Washington and marched into Philadelphia unopposed on September 26. Washington's army unsuccessfully attacked the British garrison at Germantown in early October. Meanwhile, Burgoyne, out of reach from help from Howe, was trapped and forced to surrender his entire army at Saratoga, New York.

France responded to Burgoyne's defeat by entering the war, openly

allying with America and turning the Revolutionary War into a major

worldwide war. Washington's army camped at Valley Forge in

December 1777, staying there for the next six months. Over the winter,

2,500 men of the 10,000-strong force died from disease and exposure.

The next spring, however, the army emerged from Valley Forge in good

order, thanks in part to a full-scale training program supervised by Baron von Steuben, a veteran of the Prussian general staff. The British evacuated Philadelphia to New York in 1778 but Washington attacked them at Monmouth and

drove them from the battlefield. Afterwards, the British continued to

head towards New York. Washington moved his army outside of New York. In the summer of 1779 at Washington's direction, General John Sullivan carried out a decisive scorched earth campaign that destroyed at least forty Iroquois villages

throughout present-day central and upstate New York in retaliation for

Iroquois and Tory attacks against American settlements earlier in the

war. Washington delivered the final blow to the British in 1781, after a French naval victory allowed American and French forces to trap a British army in Virginia. The surrender at Yorktown on

October 17, 1781, marked the end of most fighting. Though known for his

successes in the war and of his life that followed, Washington suffered

many defeats before achieving victory. In March 1783, Washington used his influence to disperse a group of Army officers who had threatened to confront Congress regarding their back pay. By the Treaty of Paris (signed

that September), Great Britain recognized the independence of the

United States. Washington disbanded his army and, on November 2, gave

an eloquent farewell address to his soldiers. On November 25, the British evacuated New York City, and Washington and the governor took possession. At Fraunces Tavern on

December 4, Washington formally bade his officers farewell and on

December 23, 1783, he resigned his commission as commander-in-chief,

emulating the Roman general Cincinnatus.

He was an exemplar of the republican ideal of citizen leadership who

rejected power. During this period, there was no position of President

of the United States under the Articles of Confederation, the forerunner to the Constitution. Washington's retirement to Mount Vernon was short-lived. He made an exploratory trip to the western frontier in 1784, was persuaded to attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in

the summer of 1787, and was unanimously elected president of the

Convention. He participated little in the debates involved (though he

did vote for or against the various articles), but his high prestige

maintained collegiality and kept the delegates at their labors. The

delegates designed the presidency with Washington in mind, and allowed

him to define the office once elected. After the Convention, his

support convinced many, including the Virginia legislature, to vote for

ratification; the new Constitution was ratified by all 13 states. The Electoral College elected Washington unanimously in 1789, and again in the 1792 election; he remains the only president to have received 100% of the electoral votes. At his inauguration, he insisted on having Barbados Rum served. John Adams was elected vice president. Washington took the oath of office as the first President under the Constitution for the United States of America on April 30, 1789, at Federal Hall in New York City although, at first, he had not wanted the position. The 1st United States Congress voted

to pay Washington a salary of $25,000 a year—a large sum in 1789.

Washington, already wealthy, declined the salary, since he valued his

image as a selfless public servant. At the urging of Congress, however,

he ultimately accepted the payment, to avoid setting a precedent

whereby the presidency would be perceived as limited only to

independently wealthy individuals who could serve without any salary.

Washington attended carefully to the pomp and ceremony of office,

making sure that the titles and trappings were suitably republican and

never emulated European royal courts. To that end, he preferred the

title "Mr. President" to the more majestic names suggested. Washington

proved an able administrator. An excellent delegator and judge of

talent and character, he held regular cabinet meetings to debate issues

before making a final decision. In handling routine tasks, he was

"systematic, orderly, energetic, solicitous of the opinion of others

but decisive, intent upon general goals and the consistency of

particular actions with them." Washington reluctantly served a second term as

president. He refused to run for a third, establishing the customary

policy of a maximum of two terms for a president which later became law

by the 22nd Amendment to the Constitution. Washington

was not a member of any political party and hoped that they would not

be formed, fearing conflict and stagnation. His closest advisors formed

two factions, setting the framework for the future First Party System. Secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamilton had bold plans to establish the national credit and build a financially powerful nation, and formed the basis of the Federalist Party. Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, founder of the Jeffersonian Republicans, strenuously opposed Hamilton's agenda, but Washington favored Hamilton over Jefferson. The Residence Act of 1790,

which Washington signed, authorized the President to select the

specific location of the permanent seat of the government, which would

be located along the Potomac River. The Act authorized the President to

appoint three commissioners to survey and acquire property for this

seat. Washington personally oversaw this effort throughout

his term in office. In 1791, the commissioners named the permanent seat

of government "The City of Washington in the Territory of Columbia" to

honor Washington. In 1800, the Territory of Columbia became the District of Columbia when the federal government moved to the site according to the provisions of the Residence Act. In 1791, Congress imposed an excise on distilled spirits,

which led to protests in frontier districts, especially Pennsylvania.

By 1794, after Washington ordered the protesters to appear in U.S. district court, the protests turned into full-scale riots known as the Whiskey Rebellion. The federal army was too small to be used, so Washington invoked the Militia Act of 1792 to

summon the militias of Pennsylvania, Virginia, and several other

states. The governors sent the troops and Washington took command,

marching into the rebellious districts. There

was no fighting, but Washington's forceful action proved the new

government could protect itself. It also was one of only two times that

a sitting President would personally command the military in the field.

These events marked the first time under the new constitution that the

federal government used strong military force to exert authority over

the states and citizens. In 1793, the revolutionary government of France sent diplomat Edmond-Charles Genêt, called "Citizen Genêt," to America. Genêt issued letters of marque and reprisal to

American ships so they could capture British merchant ships. He

attempted to turn popular sentiment towards American involvement in thebFrench war against Britain by creating a network of Democratic-Republican Societies in

major cities. Washington rejected this interference in domestic

affairs, demanded the French government recall Genêt, and

denounced his societies. Hamilton and Washington designed the Jay Treaty to

normalize trade relations with Britain, remove them from western forts,

and resolve financial debts left over from the Revolution. John Jay negotiated

and signed the treaty on November 19, 1794. The Jeffersonians supported

France and strongly attacked the treaty. Washington and Hamilton,

however, mobilized public opinion and won ratification by the Senate by

emphasizing Washington's support. The British agreed to depart their

forts around the Great Lakes,

the Canadian-U.S. boundary was adjusted, numerous pre-Revolutionary

debts were liquidated, and the British opened their West Indies

colonies to American trade. Most importantly, the treaty delayed war

with Britain and instead brought a decade of prosperous trade with that

country. This angered the French and became a central issue in

political debates. Washington's

Farewell Address (issued as a public letter in 1796) was one of the

most influential statements of American political values. Drafted

primarily by Washington himself, with help from Hamilton, it gives

advice on the necessity and importance of national union, the value of

the Constitution and the rule of law, the evils of political parties,

and the proper virtues of a republican people. Washington's

public political address warned against foreign influence in domestic

affairs and American meddling in European affairs. He warned against

bitter partisanship in domestic politics and called for men to move

beyond partisanship and serve the common good. He

counseled friendship and commerce with all nations, but warned against

involvement in European wars and entering into long-term "entangling"

alliances. After

retiring from the presidency in March 1797, Washington returned to

Mount Vernon with a profound sense of relief. He devoted much time to farming. On December 18, 1799, a funeral was held at Mount Vernon, and Washington was interred in a tomb on the estate.

As

a colonial militia officer, albeit a high ranking one, Washington was

acutely conscious of the disparity between officers in the militia and the regular British Army establishment.

His eldest brother Lawrence had been fortunate to be awarded a

commission in the British Army, as "Captain in a Regiment of Foot", in

summer 1740, when the British Army raised a new regiment (the 61st Foot, known as Gooch's American Regiment) in the colonies, for service in the West Indies during the War of Jenkins' Ear. Each

colony was allowed to appoint its own company officers—the captains and

lieutenants—and signed commissions were distributed by Colonel William

Blakeney to the various governors. Fifteen years later, when General Braddock arrived in Virginia in 1755 with two regiments of regulars (the 44th and 48th Foot), Washington sought to obtain a commission, but none were available for purchase. Rather

than serve as a militia lieutenant colonel, where he would be outranked

by more junior officers in the regulars, Washington chose to serve in a

private capacity as aide-de-camp to the general; as an aide, he could

command British regulars. Following

Braddock's defeat, the British Parliament decided in November 1755 to

create a new Royal American Regiment of Foot—later renamed King's Royal Rifle Corps. Unlike the earlier "American Regiment" of 1740–42, all of the officers were recruited in England and Europe in early 1756.

Washington's

marriage to Martha, a wealthy widow, greatly increased his property

holdings and social standing. He acquired one-third of the

18,000 acre (73 km²) Custis estate upon his marriage,

and managed the remainder on behalf of Martha's children. He frequently

bought additional land in his own name. In addition, he was granted

land in what is now West Virginia as

a bounty for his service in the French and Indian War. By 1775,

Washington had doubled the size of Mount Vernon to 6,500 acres

(26 km2), and had increased

the slave population there to more than 100 persons. As a respected

military hero and large landowner, he held local office and was elected

to the Virginia provincial legislature, the House of Burgesses, beginning in 1758.

On July 4, 1798, Washington was commissioned by President John Adams to be Lieutenant General and Commander-in-chief of the armies raised or to be raised for service in a prospective war with France. He served as the senior officer of the United States Army between

July 13, 1798, and December 14, 1799. On

December 12, 1799, Washington spent several hours inspecting his farms

on horseback, in snow and later hail and freezing rain. He sat down to

dine that evening without changing his wet clothes. The next morning,

he awoke with a bad cold, fever, and a throat infection called quinsy that turned into acute laryngitis and pneumonia. Washington died on the evening of December 14, 1799, at his home aged 67.