<Back to Index>

- Anatomist Giovanni Battista Morgagni, 1682

- Painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1841

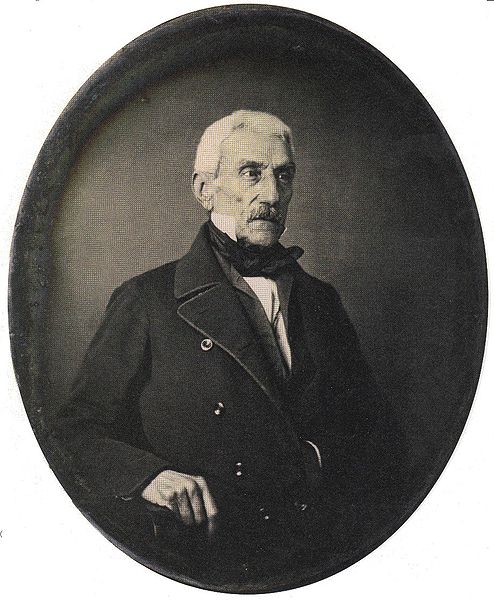

- General José Francisco de San Martín Matorras, 1778

José Francisco de San Martín Matorras, also known as José de San Martín (25 February 1778 – 17 August 1850), was an Argentine general and the prime leader of the southern part of South America's successful struggle for independence from Spain.

Born on 25 February 1778 in Yapeyú, Corrientes in Argentina, he left his mother country at the early age of seven and studied in an aristocratic school in Madrid, Spain, where he met and befriended Chilean Bernardo O'Higgins.

In 1808, after joining Spanish forces in their fight against the

French, and after participating in several battles such as the Battle of Bailén, José started making contact with South American supporters of independence from Spain. In 1812, he set sail for Buenos Aires from England, and offered his services to the United Provinces of South America (present-day Argentina). After the Battle of San Lorenzo of 1813, and some time on command of the Army of the North during 1814, he started to put into action his plan to defeat the Spanish forces that menaced the United Provinces from Upper Perú, making use of an alternative path to the Viceroyalty of Perú. This objective first involved the creation of a new army, the Army of the Andes, in the Province of Cuyo, Argentina. From there, he led the Crossing of the Andes to Chile, and prevailed over the Spanish forces at the Battle of Chacabuco and the Battle of Maipú (1818), thus liberating Chile from Royalist rule. Then he set sail to attack the Spanish stronghold of Lima, Perú, by sea. On 12 July 1821, after seizing partial control of Lima, San Martín was appointed Protector of Perú, and Peruvian independence was officially declared on 28 July 1821. A year later, after a closed-door meeting with fellow libertador Simón Bolívar at Guayaquil, Ecuador, on 22 July 1822, Bolívar took over the task of fully liberating Peru.

San Martín unexpectedly left the country and resigned the

command of his army, excluding himself from politics and the military,

and moved to France in 1824. The details of the 22 July meeting would

be a subject of debate by later historians. Together with Simón Bolívar, San Martín is regarded as one of the Liberators of Spanish South America. He is the national hero of Argentina. The Order of the Liberator General San Martin (Spanish: Orden del Libertador San Martín) in his honor is the highest decoration in Argentina. Son of Spaniard Juan de San Martin y Gómez, born in Cervatos de la Cueza on 12 February 1728, and wife Gregoria Matorras, he was born the fifth and last child in 25 February 1778 in Yapeyú, a small village in Corrientes, Argentina. His father was a Colonel in office as Lieutenant Governor of Yapeyú beginning in 1774. In 1781, the family moved to Buenos Aires. In

1785, his father was transferred again, this time to Spain. And so the

family moved to Spain, and San Martín enrolled in Madrid's Real

Seminario de Nobles where he studied from 1785. While at the Real

Seminario de Nobles he met and became friends with Bernardo O'Higgins. In

1789, aged eleven, San Martín left the Real Seminario de Nobles

and enrolled in the Regiment of Murcia, starting his military career as

a cadet in the Unidad de Infantería Murcesa (Murcian Infantry Unit). After joining the Regiment of Murcia, San Martín participated in several campaigns in Africa, fighting in Oran against the Moors in 1791 among other places. Later, by the end of the First Coalition of the French Revolutionary Wars in 1797, his rank was raised to Sub-Lieutenant for his actions against the French in the Pyrenees. On August of the same year, after several engagements, his regiment surrendered to British naval forces in 1798. Soon afterward, he continued to fight in southern Spain, mainly in Cádiz and Gibraltar with the rank of Second Captain of light infantry. He continued to fight Portugal on the side of Spain in the War of the Oranges in 1801, and was soon after promoted to captain in 1804. When the Peninsular War started in 1808, San Martín was assigned ayudante of the First Regiment Voluntarios de Campo Mayor.

After his actions against the French, he became Captain of the Regiment

of Borbon. On 19 July 1808, Spanish and French forces engaged in the Battle of Bailén, in which Spanish forces prevailed, allowing the Army of Andalucia to attack and seize Madrid.

For his actions during this battle, San Martín was decorated

with a gold medal, and his rank raised to Lieutenant Colonel. While in Spain, San Martín became acquainted with several criollos (creoles), and became aware of the independence movements in America. On 16 May 1811, he participated in the Battle of Albuera under the command of general William Carr Beresford. During the battle he met Scottish Lord MacDuff (James Duff, 4th Earl of Fife)

who introduced him to the lodges that were plotting the South American

independence efforts. San Martín requested resignation from the

Spanish army, which was granted. Throughout

his time serving in Spain he experienced hindrances and prejudices in

his career and life in general because he was born in the Americas.

Although he only lived there for a short time and had Spanish parents

his career and social mobility was limited. With the help of Lord MacDuff, San Martín obtained a passport to England where he met several criollos, American-born Spaniards like himself, who were part of the Logia de los Caballeros Racionales (Lodge of the Rational Knights) founded by the Venezuelan Francisco de Miranda. According to Argentine historian Felipe Pigna, San Martín was introduced to the Maitland Plan by members of the lodge founded by Miranda and Lord MacDuff. In 1812, San Martín set sail for Buenos Aires aboard the British frigate George Canning. Following his arrival in Buenos Aires on 9 March 1812, his rank of Lieutenant Colonel was recognized by the Triumvirate and he was thus entrusted with the creation of the Regiment of Mounted Grenadiers (Regimiento de Granaderos a Caballo), which would become the best-trained military arm of the revolution. In Córdoba, San Martín continued preparing his plan of attacking Lima — the Capital city of the Viceroyalty of Peru — through Chile.

He realized that it would be impossible to enter the large city without

having conquered the land to the south. To this end, he requested to be

appointed governor of the Province of Cuyo. Later, Juan Pueyrredón was

sent by the provisional government of the United Provinces of the

Río de la Plata, and gave San Martín full support on his Liberatory Campaign (Spanish: Campaña Libertadora). One

month after he took office, royalist forces defeated rebel forces under

Bernardo O'Higgins' command (O'Higgins fled to the Andes). During his governorship of Cuyo, he organized the Army of Cuyo. On 8 November 1814 he created the 11th Battalion of Infantry (Batallón Número 11 de Infantería) which included the Corps of Chile (Cuerpo de Chile), which was under command of Argentine Lieutenant Colonel Juan Gregorio de las Heras. On 1 August 1816, Pueyrredón renamed the army to Army of the Andes (Ejército de los Andes), appointed San Martín as its General in Chief, and gave the Army a national priority level. By the end of this difficult process, San Martin’s army had grown immensely. In September 1816, San Martín relocated his Army of the Andes to Plumerillo, in the northern part of Mendoza Province,

where he finished the details to start his crossing of the Andes. The

army was divided in two main columns and four minor ones, keeping the

decided paths in secret. On 18 January 1817, a main column parted with the artillery to Chile through Uspallata, under command of General Las Heras, reaching Las Cuevas on 1 February 1817. The second main column, led by San Martín, left on 19 January through Los Patos pass, and reached San Andrés de Tártaro on

8 February, where he was later joined by Las Heras, concluding the

first part of the crossing. By the time the main columns reunited, both

had already had minor skirmishes: the first column had fought royalists

in Potrerillos, while the forces led by San Martín had fought the Battles of Achupallas and Las Coimas. The crossing of the Andes was

extremely difficult and took 21 days due to high altitudes and low

temperature. It is considered a major feat in military history. After crossing the Andes and entering Chile, the Spanish royalist forces were taking positions in Mount Cuesta Vieja,

preparing themselves for the confrontation against the Army of the

Andes. By 10 February 1817, the Army of the Andes was in the Aconcagua valley,

and the Spanish royalist forces had not still taken full positions. San

Martín then took the initiative and hastened preparations for

his attack. Despite a severe attack of Rheumatoid arthritis,

San Martín commanded the battle, and seeing the Spanish forces

under numerical inferiority and considering the surprise factor,

developed a strategy for the Spanish forces to surrender, avoiding

bloodshed. The charge was a stalemate until Soler's division joined the

battle turning the odds in favor of the patriot side. After

the battle, the royalist forces had suffered five hundred casualties

and six hundred royalist soldiers had been taken prisoner. On the Army

of the Andes side, there were twelve killed and around one hundred

wounded. The army also gained new artillery and other weapons, besides

restoring the Chilean revolution. On

14 February 1817, San Martín and O'Higgins triumphally entered

Santiago, and on 18 February, in a meeting held in the town open hall,

San Martín was appointed Governor of Chile. San Martín

immediately resigned, thus O'Higgins was elected Supreme Director of

the State of Chile (Director Supremo del Estado de Chile). The United Army (Ejército Unido)

was created with Chilean and Argentine soldiers. The Chilean soldiers

were under O'Higgins command, while San Martín was General in

Chief of the whole United Army. Then

San Martín, in order to raise funds for a fleet, left for Buenos

Aires. After negotiating with Pueyrredón, a delegation was sent

to London to provide ships for a new fleet in the Pacific Ocean. Back

in Chile in the last days of 1817, San Martín sent a delegation

to Lima under the pretext of proposing to the Viceroy Joaquín de la Pezuela of Peru the regularization of the war and exchange of POWs.

The real purpose was to gain as much information as possible about the

enemy's plans. The delegation brought the news that a Spanish army

under General Mariano Osorio was about to set sail in four frigates to southern Chile. Despite

the success in the Battle of Chacabuco, and while leaving Santiago and

the northern Chile under patriot control, the royalist forces still had

strong presence in southern Chile. The men under Osorio's command

joined the royalist forces in the south by sea. The royalists also had

allied themselves with Mapuche native Americans. On 19 March 1818, the royalist forces concentrated and fortified in Talca with

around five thousand men under General Osorio, while the independent

forces of around seven thousand men formed by the United Army were

taking positions in the Cancha Rayada plains. San Martín, fearing an attack on his flank, ordered a change of position of the troops. Knowing

their disadvantage in number and cavalry, the Spanish General Mariano

Osorio was not eager to engage in battle, fortifying in Talca. However,

after a suggestion from Colonel José Ordóñez a

confrontation was decided upon, under Ordoñez' command. In a

bold move, Ordoñez made the kind of attack San Martín had

feared: circumventing the city and making a surprise attack at night

behind the vanguard where the patriot forces were still taking

positions. The surprise attack happened before the patriot army had

re-positioned itself, and was directed at the battalion under

O'Higgins command, near San Martín's position. Soon, the

vanguard soldiers dispersed, leaving O'Higgins in a bad position; his

horse was shot dead and he was wounded in one arm. In an

uncharacteristic move, instead of ordering retreat San Martín

held the position, which made more patriot soldiers flee under enemy

fire, leaving weapons and supplies behind. After the initial disorder,

however, he ordered retreat. The rear and reserves had already

re-positioned, somewhat withstanding the attack, but had no-one in

command (Colonel Hilarión de la Quintana had

left to headquarters to receive orders after the re-position and had

not yet returned). Las Heras took command, and led the men during the

retreat, while trying to recover as much artillery and weapons as

possible. San Martín and O'Higgins (who were also retreating at

full speed) were being closely chased by royalist forces. By

21 March 1818, the decimated patriot forces of around three and half

thousand men reunited in San Fernando, while news of the defeat reached

Santiago. Rumors of deaths of O'Higgins and San Martín were

spreading, and an exodus from Santiago to Mendoza started. After the sorpresa de Cancha Rayada (surprise

of Cancha Rayada), the royalist forces concentrated and marched towards

Santiago. On 4 April 1818, the United Army took positions in Loma

Blanca, near the Maipú plains. The army separated into three

divisions: Las Heras commanding the column on the right, Colonel Rudecindo Alvarado commanding the column on the left, and Quintana at the rear. O'Higgins (still wounded) was in charge of the reserves. The

royalist forces under General Osorio's command took defensive

positions, despite the convictions of some Colonels (among whom was

Ordoñez) that taking the offensive as in Cancha Rayada was the

best option. Around

11 am on the morning of 5 April 1818, the patriotic forces charged

against the royalist forces with devastating resolution: after the

sustained six-hour battle, the royalists were defeated. Osorio

attempted to retreat to a property called Lo Espejos (The Mirrors) but failing to reach it, fled to Talcahuano with around twelve hundred men, although virtually rendered useless as they had lost most, if not all, of their weapons. As a

result of the battle, the Spanish control over southern Chile ended,

and the independence declared on 12 February 1818 was partially

accomplished. Viceroy Pezuela considered southern Chile lost, and

Osorio set sail for Peru, leaving Colonel Juan Francisco Sánchez in charge of one thousand men in Talcahuano. Right

after the Battle of Maipú, San Martín left for Buenos

Aires in order to speed up the process of acquiring a fleet (and meet his wife and daughter

which he had not seen since the start of the Campaign of the Andes).

Once in Buenos Aires, after learning the fact that half a million pesos

would not be available for the project from Pueyrredón, San

Martín resigned as Commander of the Army under the pretext of

being prescribed by his doctor to take rest in Chile's hotsprings. The

resignation was not accepted and San Martín was granted a

license. After Supreme Director José Rondeau was defeated in the Battle of Cepeda, San Martín sent his resignation of the Army's command from Santiago to Rancagua,

where Colonel Las Heras had settled with the army, arguing that the

authority to which he had to report had ceased to exist, and thus his

own authority had expired. The officials of the army rejected his

resignation on the basis that the army's goal was to hasten the happiness of the country and the authority was given ultimately by the health of the people, something that was immutable and could not expire. On 20 August 1820, a fleet of eight warships and sixteen transport ships of the Chilean Navy, under the command of Thomas Alexander Cochrane, 10th Earl of Dundonald, set sail from Valparaíso to Paracas, southern Peru.

During

1812, he focused on training troops by following the modern warfare

techniques he had acquired during the Peninsular War. With Carlos María de Alvear and José Matias Zapiola, he also established the Logia Lautaro (Lautaro Lodge), an offspring in Buenos Aires of the independence lodges in London and Cádiz. On August of the same year, he married María de los Remedios de Escalada, a young woman from one of the local wealthy families. In October, when news of the victory of the Army of the North (Ejército del Norte) commanded by Manuel Belgrano reached

Buenos Aires, the Lautaro Lodge initiated political pressure, backed by

San Martín armed forces and popular demand, to impose its

candidates into government, thus forcing the First Triumvirate to an

end and initiating the Second Triumvirate with members Juan José Paso, Nicolás Rodríguez Peña, and Antonio Álvarez Jonte (Rodríguez

Peña and Álvarez Jonte were members of the lodge). This

new government strengthened the position held by the Army, and decided

to lay siege to Montevideo, which was controlled by loyalists to the Spanish Crown. On 7 December 1812, San Martín was promoted to Colonel. Although not technically a battle (in Spanish the battle is referred as Combate de San Lorenzo ("San Lorenzo Combat")), references in English language refer to the event as the "Battle of San Lorenzo". On 28 January 1813, San Martín with his Regiment of Mounted Grenadiers was sent to protect the Paraná River shore from the Spanish Fleet ships under command of General José Zavala.

On the morning of 3 February, the Spanish forces disembarked and fought

against San Martín in the Battle of San Lorenzo. During

the fight, San Martín's horse was shot dead and fell, trapping

one of San Martín's legs underneath the dead horse. This made

him an easy target, but Sergeant Juan Bautista Cabral helped

him extricate himself. While he was helping the Colonel, Cabral was

attacked himself, and died from his wounds after the battle. After the

battle, San Martín was promoted to General. This was San

Martín's first military action in South America. After the victories of Tucuman and Salta, the Army of the North, commanded by Manuel Belgrano, lost much ground after serious defeats at Vilcapugio (1 October) and Ayohuma (14

November 1813). The Triumvirate then decided to send San Martín

to the North with a small infantry army and his cavarly regiment. After joining the defeated Army of the North in Yatasto, he took command of it on January 1814, and Belgrano became second in command. During his command, the Army camped in Tucumán, where he started instructing the troops, created a new military school, and sent Colonel Martín Miguel de Güemes to fight against loyalists coming from Peru to gain time. However, after minor struggles in Salta and Jujuy, news of the victory of Commander Guillermo Brown against the royalists' navy, and the resulting blockade of Montevideo, made the loyalist forces from Peru retreat to regroup. During his command of the Army of the North, San Martín confirmed one of the reasons behind the Maitland Plan's scheme: royalist forces that came down from Upper Perú (roughly present day Bolivia)

were easily defeated by the independentist forces in the valleys of

Salta and Jujuy. But because of the geographical advantage, forces

attacking Upper Peru were easily defeated by the royalists for the very

same reasons.

On 26 July 1822, he met with Simón Bolívar at Guayaquil to plan the future of Latin America.

Most of the details of this meeting were secret at the time, and this

has made the event a matter of much debate among later historians. Some

believe that Bolívar's refusal to share command of the combined

forces made San Martín withdraw from Peru and resettle as a

farmer in Mendoza, Argentina. Another theory claims that San

Martín yielded to Bolívar's energy and avoided a

confrontation. Many argue that San Martin was a military genius but not

as charismatic a leader, or as politically ambitious, as Bolivar. In 1824, soon after his return to Argentina, his wife Remedios de Escalada de San Martín died. Then he moved to Europe with his daughter Mercedes, first to England, then to Brussels. To keep a neutral position during the 1830 Belgian Revolution he moved to Paris, where he contracted cholera. Cured but weakened, he bought a house and retired at Grand-Bourg, near Evry. His daughter married Mariano Antonio Severo de Balcarce, illegitimate son of Juan Manuel de Rosas, in Paris on 13 December 1832, and they had two daughters. In 1848, when the revolution started in Paris, he decided to move to London, but settled instead at Boulogne-sur-Mer, where he spent the remainder of his days. He

always excluded himself from every possible meddling at the internecine

wars of his home country, and refused several offers he had to do so.

The only ocasion in which he offered himself to return to Argentina was

at the time of the French Blockades of

1838 and 1845. In recognition of the succesful defense of Argentine

rights in those crises, he handed down his sword to Buenos Aires

Province Governor Juan Manuel de Rosas through his will. He died on 17 August 1850. In 1880 his remains were taken from Brunoy to Buenos Aires and reinterred in the Buenos Aires Cathedral.