<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Luitzen Egbertus Jan Brouwer, 1881

- Painter Carel Fabritius, 1622

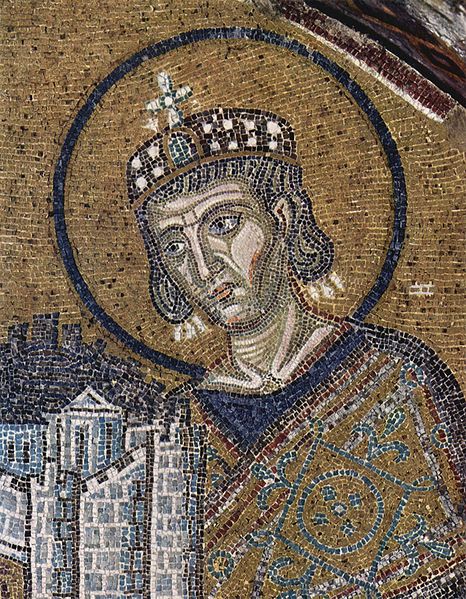

- Roman Emperor Caesar Flavius Valerius Aurelius Constantinus Augustus, 272

Caesar Flavius Valerius Aurelius Constantinus Augustus (27 February c. 272 – 22 May 337), commonly known in English as Constantine I, Constantine the Great, or (among Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic Christians) Saint Constantine was Roman emperor from 306, and the sole holder of that office from 324 until his death in 337. Best known for being the first Christian Roman emperor, Constantine reversed the persecutions of his predecessor, Diocletian, and issued (with his co-emperor Licinius) the Edict of Milan in 313, which proclaimed religious toleration throughout the empire.

The Byzantine liturgical calendar, observed by the Eastern Orthodox Church and Eastern Catholic Churches of Byzantine rite, lists both Constantine and his mother Helena as saints. Although he is not included in the Latin Church's list

of saints, which does recognize several other Constantines as saints,

he is revered under the title "The Great" for his contributions to Christianity. Constantine also transformed the ancient Greek colony of Byzantium into a new imperial residence, Constantinople, which would remain the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire for over one thousand years. As the emperor who empowered Christianity throughout the Roman Empire and moved the Roman capital to the banks of the Bosphorus, Constantine was a ruler of major historical importance, but he has always been a controversial figure. The

fluctuations in Constantine's reputation reflect the nature of the

ancient sources for his reign.

Constantine, named Flavius Valerius Constantinus, was born in the Moesian military city of Naissus (modern-day Niš, Serbia), Illyricum on the 27th of February of an uncertain year, probably near 272. His father was Flavius Constantius, a native of today Bulgaria (later Dacia Ripensis). Constantius was a tolerant and politically skilled man. He was an officer in the Roman army in 272, part of the Emperor Aurelian's imperial bodyguard. Constantius advanced through the ranks, earning the governorship of Dalmatia from Emperor Diocletian, another of Aurelian's companions from Illyricum, in 284 or 285. Constantine's mother was Helena, a Bithynian Greek of humble origin. It is uncertain whether she was legally married to Constantius or merely his concubine. In July 285, Diocletian declared Maximian, another colleague from Illyricum,

his co-emperor. Each emperor would have his own court, his own military

and administrative faculties, and each would rule with a separate praetorian prefect as chief lieutenant. Maximian ruled in the West, from his capitals at Mediolanum (Milan, Italy) or Augusta Treverorum (Trier, Germany), while Diocletian ruled in the East, from Nicomedia (İzmit, Turkey). The division was merely pragmatic: the Empire was called "indivisible" in official panegyric, and both emperors could move freely throughout the Empire. In 288, Maximian appointed Constantius to serve as his praetorian prefect in Gaul. Constantius left Helena to marry Maximian's stepdaughter Theodora in 288 or 289. Diocletian divided the Empire again in 293, appointing two Caesars (junior emperors) to rule over further subdivisions of East and West. Each would be subordinate to their respective Augustus (senior emperor) but would act with supreme authority in his assigned lands. This system would later be called the Tetrarchy. Diocletian's first appointee for the office of Caesar was Constantius; his second was Galerius, a native of Felix Romuliana (Illyria).

On 1 March, Constantius was promoted to the office of Caesar, and dispatched to Gaul to fight the rebels Carausius and Allectus. In spite of meritocratic overtones, the Tetrarchy retained vestiges of hereditary privilege, and

Constantine became the prime candidate for future appointment as Caesar

as soon as his father took the position. Constantine left the Balkans

for the court of Diocletian, where he lived as his father's heir

presumptive. Constantine received a formal education at Diocletian's court, where he learned Latin literature, Greek, and philosophy. The

cultural environment in Nicomedia was open, fluid and socially mobile,

and Constantine could mix with intellectuals both pagan and Christian.

He may have attended the lectures of Lactantius, a Christian scholar of

Latin in the city. Because

Diocletian did not completely trust Constantius—none of the Tetrarchs

fully trusted their colleagues—Constantine was held as something of a

hostage, a tool to ensure Constantius' best behaviour. Constantine was

nonetheless a prominent member of the court: he fought for Diocletian

and Galerius in Asia, and served in a variety of tribunates;

he campaigned against barbarians on the Danube in 296, and fought the

Persians under Diocletian in Syria (297) and under Galerius in

Mesopotamia (298–99). By late 305, he had become a tribune of the first order, a tribunus ordinis primi. Constantine

had returned to Nicomedia from the eastern front by the spring of 303,

in time to witness the beginnings of Diocletian's "Great Persecution", the most severe persecution of Christians in Roman history. In late 302, Diocletian and Galerius sent a messenger to the oracle of Apollo at Didyma with an inquiry about Christians. Constantine

could recall his presence at the palace when the messenger returned,

when Diocletian accepted his court's demands for universal persecution. On

23 February 303, Diocletian ordered the destruction of Nicomedia's new

church, condemned its scriptures to the flame, and had its treasures

seized. In the months that followed, churches and scriptures were

destroyed, Christians were deprived of official ranks, and priests were

imprisoned. On

1 May 305, Diocletian, as a result of a debilitating sickness taken in

the winter of 304–5, announced his resignation. In a parallel ceremony

in Milan, Maximian did the same. Constantius and Galerius were promoted to Augusti, while Severus and Maximin were appointed their Caesars respectively. Constantine and Maxentius were ignored. Constantine

recognized the implicit danger in remaining at Galerius' court, where

he was held as a virtual hostage. His career depended on being rescued

by his father in the west. Constantius was quick to intervene. In

the late spring or early summer of 305, Constantius requested leave for

his son, to help him campaign in Britain. After a long evening of

drinking, Galerius granted the request. Constantine's later propaganda

describes how Constantine fled the court in the night, before Galerius

could change his mind. By the time Galerius awoke the following morning, Constantine had fled too far to be caught. Constantine joined his father in Gaul, at Bononia (Boulogne) before the summer of 305. From Bononia they crossed the Channel to Britain and made their way to Eboracum (York), capital of the province of Britannia Secunda and

home to a large military base. Constantius had become severely sick over the course of his reign, and died on 25 July 306 in Eboracum (York). Before dying, he declared his support for raising Constantine to the rank of full Augustus. The Alamannic king Chrocus,

a barbarian taken into service under Constantius, then proclaimed

Constantine as Augustus. The troops loyal to Constantius' memory

followed him in acclamation. Gaul and Britain quickly accepted his rule; Iberia, which had been in his father's domain for less than a year, rejected it.

Constantine

sent Galerius an official notice of Constantius's death and his own

acclamation. Galerius

was put into a fury by the message but he was compelled to compromise: he granted Constantine the title "Caesar"

rather than "Augustus" (The latter office went to Severus instead). Constantine accepted the decision, knowing that it would remove doubts as to his legitimacy. Constantine's

share of the Empire consisted of Britain, Gaul, and Spain. He therefore

commanded one of the largest Roman armies, stationed along the important Rhine frontier. After his promotion to emperor, Constantine remained in Britain, and secured his control in the northwestern dioceses.

He completed the reconstruction of military bases begun under his

father's rule, and ordered the repair of the region's roadways. He soon left for Augusta Treverorum (Trier) in Gaul, the Tetrarchic capital of the northwestern Roman Empire. The Franks, after learning of Constantine's acclamation, invaded Gaul across the lower Rhine over the winter of 306–7. Constantine

drove them back beyond the Rhine and captured two of their kings,

Ascaric and Merogaisus. Constantine

began a major expansion of Trier. Constantine sponsored

many building projects across Gaul during his tenure as emperor of the

West, especially in Augustodunum (Autun) and Arelate (Arles).

Constantine followed his father in following a tolerant

policy towards Christianity. He decreed a formal end to persecution,

and returned to Christians all they had lost during the persecutions. Following

Galerius' recognition of Constantine as emperor, Constantine's portrait

was brought to Rome, as was customary. Maxentius mocked the portrait's

subject as the son of a harlot, and lamented his own powerlessness. Maxentius, jealous of Constantine's authority, seized the title of emperor on 28 October 306. Galerius refused to recognize him, but failed to unseat him. Galerius sent Severus against

Maxentius, but during the campaign, Severus' armies, previously under

command of Maxentius's father Maximian, defected, and Severus was

seized and imprisoned. Maximian,

brought out of retirement by his son's rebellion, left for Gaul to

confer with Constantine in late 307. He offered to marry his daughter Fausta to

Constantine, and elevate him to Augustan rank. In return, Constantine

would reaffirm the old family alliance between Maximian and

Constantius, and offer support to Maxentius' cause in Italy.

Constantine accepted, and married Fausta in Trier in late summer 307.

Constantine now gave Maxentius his meager support, offering Maxentius

political recognition. Constantine

remained aloof from the Italian conflict, however. Over the spring and

summer of 307, he had left Gaul for Britain to avoid any involvement in

the Italian turmoil; now,

instead of giving Maxentius military aid, he sent his troops against

Germanic tribes along the Rhine. In 308, he raided the territory of the Bructeri, and made a bridge across the Rhine at Colonia Agrippinensium (Cologne).

In 310, he marched to the northern Rhine and fought the Franks. When

not campaigning, he toured his lands advertising his benevolence, and

supporting the economy and the arts. His refusal to participate in the

war increased his popularity among his people, and strengthened his

power base in the West. Maximian

returned to Rome in the winter of 307–8, but soon fell out with his

son. In early 309, after a failed attempt to usurp Maxentius' title,

Maximian returned to Constantine's court. In

310, a dispossessed and power-hungry Maximian rebelled against

Constantine while Constantine was away campaigning against the Franks.

Maximian had been sent south to Arles with a contingent of

Constantine's army, in preparation for any attacks by Maxentius in

southern Gaul. He announced that Constantine was dead, and took up the

imperial purple. In spite of a large donative pledge to any who would

support him as emperor, most of Constantine's army remained loyal to

their emperor, and Maximian was soon compelled to leave. Constantine

soon heard of the rebellion, abandoned his campaign against the Franks,

and marched his army up the Rhine. At Cabillunum (Chalon-sur-Saône), he moved his troops onto waiting boats to row down the slow waters of the Saône to the quicker waters of the Rhone. He disembarked at Lugdunum (Lyon). Maximian fled to Massilia (Marseille),

a town better able to withstand a long siege than Arles. It made little

difference, however, as loyal citizens opened the rear gates to

Constantine. Maximian was captured and reproved for his crimes.

Constantine granted some clemency, but strongly encouraged his suicide.

In July 310, Maximian hanged himself. By the middle of 310 Galerius had become too ill to involve himself in imperial politics. His

final act survives: a letter to the provincials posted in Nicomedia on

30 April 311, proclaiming an end to the persecutions, and the

resumption of religious toleration. He died soon after the edict's proclamation, destroying what little remained of the tetrarchy. Maximin mobilized against Licinius, and seized Asia Minor. A hasty peace was signed on a boat in the middle of the Bosphorus. While Constantine toured Britain and Gaul, Maxentius prepared for war. He fortified northern Italy, and strengthened his support in the Christian community by allowing it to elect a new Bishop of Rome, Eusebius. Maxentius'

rule was nevertheless insecure. His early support dissolved in the wake

of heightened tax rates and depressed trade; riots broke out in Rome and Carthage; and Domitius Alexander was able to briefly usurp his authority in Africa. In

the summer of 311, Maxentius mobilized against Constantine while

Licinius was occupied with affairs in the East. He declared war on

Constantine, vowing to avenge his father's "murder". To prevent Maxentius from forming an alliance against him with Licinius, Constantine

forged his own alliance with Licinius over the winter of 311–12, and

offered him his sister Constantia in marriage. Maximin considered

Constantine's arrangement with Licinius an affront to his authority. In

response, he sent ambassadors to Rome, offering political recognition

to Maxentius in exchange for a military support. Maxentius accepted. Constantine's advisers and generals cautioned against preemptive attack on Maxentius. Constantine ignored all these cautions. Early in the spring of 312, Constantine crossed the Cottian Alps with a quarter of his army, a force numbering about 40,000. The first town his army encountered was Segusium (Susa, Italy),

a heavily fortified town that shut its gates to him. Constantine

ordered his men to set fire to its gates and scale its walls. He took

the town quickly. Constantine ordered his troops not to loot the town,

and advanced with them into northern Italy. At the approach to the west of the important city of Augusta Taurinorum (Turin, Italy), Constantine met a large force of heavily armed Maxentian cavalry. In the ensuing battle Constantine's

army encircled Maxentius' cavalry, flanked them with his own cavalry,

and dismounted them with blows from his soldiers' iron-tipped clubs.

Constantine's armies emerged victorious. Turin refused to give refuge to Maxentius' retreating forces, opening its gates to Constantine instead. Other

cities of the north Italian plain sent Constantine embassies of

congratulation for his victory. He moved on to Milan, where he was met

with open gates and jubilant rejoicing. Constantine rested his army in

Milan until mid-summer 312, when he moved on to Brixia (Brescia). Brescia's army was easily dispersed, and Constantine quickly advanced to Verona, where a large Maxentian force was camped. Ruricius Pompeianus, general of the Veronese forces and Maxentius' praetorian prefect, was in a strong defensive position, since the town was surrounded on three sides by the Adige.

Constantine sent a small force north of the town in an attempt to cross

the river unnoticed. Ruricius sent a large detachment to counter

Constantine's expeditionary force, but was defeated. Constantine's

forces successfully surrounded the town and laid siege. Ruricius

gave Constantine the slip and returned with a larger force to oppose

Constantine. Constantine refused to let up on the siege, and sent only

a small force to oppose him. In the desperately fought encounter that followed, Ruricius was killed and his army destroyed. Verona surrendered soon afterwards, followed by Aquileia, Mutina (Modena), and Ravenna. The road to Rome was now wide open to Constantine. Maxentius prepared for the same type of war he had waged against Severus and Galerius: he sat in Rome and prepared for a siege. He

still controlled Rome's praetorian guards, was well-stocked with

African grain, and was surrounded on all sides by the seemingly

impregnable Aurelian Walls. He ordered all bridges across the Tiber cut and left the rest of central Italy undefended; Constantine secured that region's support without challenge. Constantine progressed slowly along the Via Flaminia, allowing the weakness of Maxentius to draw his regime further into turmoil. On 28 October 312 Maxentius advanced north to meet Constantine in

battle. Maxentius

organized his forces—still twice the size of Constantine's—in long

lines facing the battle plain, with their backs to the river. Constantine

deployed his own forces along the whole length of Maxentius' line. He

ordered his cavalry to charge, and they broke Maxentius' cavalry. He

then sent his infantry against Maxentius' infantry, pushing many into

the Tiber where they were slaughtered and drowned. Constantine entered Rome on 29 October. He staged a grand adventus in the city, and was met with popular jubilation. He choose to honor the Senatorial Curia with a visit, where

he promised to restore its ancestral privileges and give it a secure

role in his reformed government: there would be no revenge against

Maxentius' supporters. In

response, the Senate acclaimed him as "the greatest Augustus". He

issued decrees returning property lost under Maxentius, recalling

political exiles, and releasing Maxentius' imprisoned opponents. In

the following years, Constantine gradually consolidated his military

superiority over his rivals in the crumbling Tetrarchy. In 313, he met Licinius in Milan to secure their alliance by the marriage of Licinius and Constantine's half-sister Constantia. During this meeting, the emperors agreed on the so-called Edict of Milan, officially granting full tolerance to "Christianity and all" religions in the Empire. The conference was cut short, however, when news reached Licinius that his rival Maximin had crossed the Bosporus and

invaded European territory. Licinius departed and eventually defeated

Maximinus, gaining control over the entire eastern half of the Roman

Empire. Relations between the two remaining emperors deteriorated,

though, and either in 314 or 316, Constantine and Licinius fought

against one another in the war of Cibalae, with Constantine being victorious. They clashed again in the Battle of Campus Ardiensis in 317, and agreed to a settlement in which Constantine's sons Crispus and Constantine II, and Licinius' son Licinianus were made caesars. In the year 320, Licinius reneged on the religious freedom promised by the Edict of Milan in 313 and began to oppress Christians anew. It became a challenge to Constantine in the west, climaxing in the great civil war of 324. Licinius, aided by Goth mercenaries, represented the past and the ancient Pagan faiths. Constantine and his Franks marched under the standard of the labarum,

and both sides saw the battle in religious terms. Supposedly

outnumbered, but fired by their zeal, Constantine's army emerged

victorious in the Battle of Adrianople. Licinius fled across the Bosphorus and appointed Martius Martinianus, the commander of his bodyguard, as Caesar, but Constantine next won the Battle of the Hellespont, and finally the Battle of Chrysopolis on 18 September 324. Licinius

and Martinianus surrendered to Constantine at Nicomedia on the promise

their lives would be spared: they were sent to live as private citizens

in Thessalonica and Cappadocia respectively, but in 325 Constantine

accused Licinius of plotting against him and had them both arrested and

hanged; Licinius's son (the son of Constantine's half-sister) was also

eradicated. Thus Constantine became the sole emperor of the Roman Empire.

Licinius' defeat represented the passing of old Rome, and the beginning of the role of the Eastern Roman Empire as a center of learning, prosperity, and cultural preservation. Constantine rebuilt the city of Byzantium, which was renamed Constantinopolis , and issued special commemorative coins in 330 to honor the event. Constantine built the new Church of the Holy Apostles on the site of a temple to Aphrodite. The capital would often be compared to the 'old' Rome as Nova Roma Constantinopolitana. Constantine

is perhaps best known for being the first Christian Roman emperor; his

reign was certainly a turning point for the Christian Church. Throughout

his rule, Constantine supported the Church financially, built

basilicas, granted privileges to clergy, promoted Christians to high office, and returned property

confiscated during the Diocletianic persecution. His most famous building projects include the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and Old Saint Peter's Basilica. In

326, Constantine made all holders of top

administrative positions senators; one could become a senator, either

by being elected praetor or (in most cases) by fulfilling a function of senatorial rank: from

then on, holding of actual power and social status were melded together

into a joint imperial hierarchy. The

Senate as a body remained devoid of any significant power;

nevertheless, the senators, who had been marginalized as potential

holders of imperial functions during the Third Century, could now

dispute such positions alongside more upstart bureaucrats. It must be noted that Constantine's reforms had to do only with the civilian administration: the military chiefs, who since the Crisis of the Third Century were mostly rank-and-file upstarts, remained outside the Senate, in which they were included only by Constantine's children.

After the runaway inflation of the third century, associated with the production of fiat money to pay for public expenses, Diocletian had tried to reestablish trustworthy minting of silver and billon coins.

Constantine forsook this conservative monetary policy, preferring

instead to concentrate on minting large quantities of good standard

gold pieces—the solidus,

72 of which made a pound of gold, the standard of silver and billon

pieces being further degraded to assure the possibility of keeping

fiduciary minting alongside a gold standard. Constantine

considered Constantinople as his capital and permanent residence. He

lived there for a good portion of his later life. He rebuilt Trajan's

bridge across the Danube, in hopes of reconquering Dacia,

a province that had been abandoned under Aurelian. In the late winter

of 332, Constantine campaigned with the Sarmatians against the Goths.

The weather and a lack of food did the Goths in; nearly one hundred

thousand died before they submitted to Roman lordship. In 334, after

Sarmatian commoners had overthrown their leaders, Constantine led a

campaign against the tribe. He won a victory in the war and extended

his control over the region, as remains of camps and fortifications in

the region indicate. Constantine resettled some Sarmatian exiles as

farmers in the Balkans and Italy, and conscripted the rest into the

army. Constantine took the title Dacius maximus in 336. In the last

years of his life Constantine made plans for a campaign against Persia.

In a letter written to the king of Persia, Shapur, Constantine had

asserted his patronage over Persia's Christian subjects and urged

Shapur to treat them well. The

letter is undatable. In response to border raids, Constantine sent

Constantius to guard the eastern frontier in 335. In 336, prince Narseh

invaded Armenia (a Christian kingdom since 301) and installed a Persian

client on the throne. Constantine then resolved to campaign against

Persia himself. He treated the war as a Christian crusade, calling for

bishops to accompany the army and commissioning a tent in the shape of

a church to follow him everywhere. Constantine planned to be baptized

in the Jordan River before

crossing into Persia. Persian diplomats came to Constantinople over the

winter of 336–7, seeking peace, but Constantine turned them away. The

campaign was called off however, when Constantine fell sick in the

spring of 337.

Constantine

did not patronize Christianity alone, however.

Constantine

had known death would soon come. Within the Church of the Holy

Apostles, Constantine had secretly prepared a final resting-place for

himself. It came sooner than he had expected. Soon after the Feast of Easter 337, Constantine fell seriously ill. He

left Constantinople for the hot baths near his mother's city of

Helenopolis (Altinova), on the southern shores of the Gulf of İzmit.

There, in a church his mother built in honor of Lucian the Apostle, he

prayed, and there he realized that he was dying. Seeking purification,

he became a catechumen, and attempted a return to Constantinople, making it only as far as a suburb of Nicomedia. He summoned the bishops, and told them of his hope to be baptized in the River Jordan,

where Christ was written to have been baptized. He requested the

baptism right away, promising to live a more Christian life should he

live through his illness. The bishops, Eusebius records, "performed the

sacred ceremonies according to custom". He chose the Arianizing bishop Eusebius of Nicomedia, bishop of the city where he lay dying, as his baptizer. In postponing his baptism, he followed one custom at the time which postponed baptism until old age or death. It was thought Constantine put off baptism as long as he did so as to be absolved from as much of his sin as possible. Constantine

died soon after at a suburban villa called Achyron, on the last day of

the fifty-day festival of Pentecost directly following Easter, on 22

May 337.