<Back to Index>

- Microbiologist Max Theiler, 1899

- Illustrator Georg Dionysius Ehret, 1708

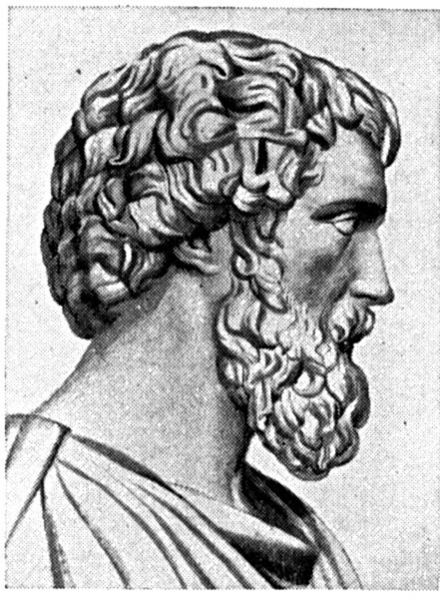

- Roman Emperor Marcus Didius Severus Julianus, 133

Marcus Didius Severus Julianus (January 30, 133/February 2 137 – June 1, 193) was briefly Roman Emperor from 28 March 193 to 1 June 193. He ascended the throne after buying it from the Praetorian Guard, who had assassinated his predecessor Pertinax. This led to the Roman Civil War of 193–197. Julianus was ousted and sentenced to death by his successor, Septimius Severus.

Julianus was born to Quintus Petronius Didius Severus and Aemilia Clara. Julianus's father came from a prominent family in Milan and his mother was an African woman, of Roman descent. Clara came from a family of consular rank. His brothers were Didius Proculus and Didius Nummius Albinus. His date of birth is given as January 30, 133 by Cassius Dio and February 2, 137 by the Historia Augusta. Didius Julianus was raised by Domitia Lucilla, mother of Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius. With Domitia's help, he was appointed at a very early age to the vigin tivirate, the first step towards public distinction. He married a Roman woman called Manlia Scantilla and about 153, Scantilla bore him a daughter and only child Didia Clara.

He held in succession the offices of Quaestor, and then Aedile, and then around 162 Julianus was named as Praetor. He was nominated to the command of the Legio XXII Primigenia in Mogontiacum (now Mainz). Starting in 170 he became praefectus of Gallia Belgica for five years. As reward for his skill and gallantry in repressing an insurrection among the Chauci, a tribe dwelling on the Elbe, he was raised to the consulship in 175, along with Pertinax. He further distinguished himself in a campaign against the Chatti, ruled Dalmatia and Germania Inferior, and then was made prefect charged with distributing money to the poor of Italy. About this time he was charged with having conspired against the life of Commodus, but had the good fortune to be acquitted, and to witness the punishment of his accuser. He also governed Bithynia, and succeeded Pertinax as the proconsul of Africa. After the initial confusion had subsided, the population did not tamely submit to the dishonour brought upon Rome. Whenever Julianus appeared in public he was saluted with groans, imprecations, and shouts of "robber and parricide." The mob tried to obstruct his progress to the Capitol, and even threw stones. When news of the public anger reached the generals in different parts of the empire, Pescennius Niger in Syria, Septimius Severus in Pannonia, and Clodius Albinus in Britain, each having three legions under his command, refused to recognize the authority of Julianus. Julianus declared Severus a public enemy because he was the nearest and therefore most dangerous foe. Deputies were sent from the Senate to persuade the soldiers to abandon him; a new general was nominated to supersede him, and a centurion dispatched to take his life. The Praetorian Guard, long strangers to active military operations, were marched into the Campus Martius, regularly drilled, and trained in the construction of fortifications and field works. Severus, however, having secured the support of Albinus by declaring him Caesar, progressed towards the city, made himself master of the fleet at Ravenna, defeated Tullius Crispinus, the Praetorian Prefect, who had been sent to halt his progress, and gained over to his cause the ambassadors sent to seduce his troops. The Praetorian Guard, lacking discipline, and sunk in debauchery and sloth, were incapable of offering any effectual resistance. Matters being desperate, Julianus now attempted negotiation, and offered to share the empire with his rival. But Severus ignored these overtures, and still pressed forwards, all Italy declaring for him as he advanced. At

last the Praetorians, having received assurances that they would suffer

no punishment, provided they would surrender the actual murderers of

Pertinax, seized the ringleaders of the conspiracy, and reported what

they had done to Silius Messala, the consul, by whom the Senate was summoned and informed of the proceedings. The Senate passed a motion proclaiming Severus emperor, awarding divine honours to Pertinax, and sentencing Julianus to death. Julianus was deserted by all except one of the prefects and his son-in-law, Repentinus. Julianus was killed in the palace by a soldier in the third month of his reign (1 June 193). Severus dismissed the Praetorian Guard and executed the soldiers who had killed Pertinax. According to Cassius Dio, who lived in Rome during the period, Julianus's last words were "But what evil have I done? Whom have I killed?" His body was given to his wife and daughter, who buried it in his great-grandfather's tomb, by the fifth milestone on the Via Labicana.

After

the murder of Pertinax (28 March 193), the Praetorian assassins

announced that the throne was to be sold to the man who would pay the

highest price. Titus Flavius Sulpicianus, prefect of the city,

father-in-law of the murdered emperor, being at that moment in the camp

to which he had been sent to calm the troops, began making offers, when Julianus, having been roused from a banquet by his wife and daughter, arrived in all haste, and being unable to gain admission, stood before the gate, and with a loud voice competed for the prize. As

the bidding went on, the soldiers reported to each of the two

competitors, the one within the fortifications, the other outside the

rampart, the sum offered by his rival. Eventually Sulpicianus promised

20,000 sesterces to every soldier, and Julianus fearing that Sulpicianus would gain the throne, immediately offered 25,000. The

guards immediately closed with the offer of Julianus, threw open the

gates, saluted him by the name of Commodus, and proclaimed him emperor. Threatened by the military, the Senate declared him emperor. His wife and his daughter both received the title Augusta.