<Back to Index>

- Chemist Sir Frederick Augustus Abel, 1827

- Painter Jean Baptiste Camille Corot, 1796

- Shahanshah of Persia Shah Ismail I, 1487

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (July 17, 1796 – February 22, 1875) was a French landscape painter and printmaker in etching. Corot was the leading painter of the Barbizon school of France in the mid-nineteenth century. He is a pivotal figure in landscape painting and his vast output simultaneously references the Neo-Classical tradition and anticipates the plein-air innovations of Impressionism.

Camille Corot was born in Paris in 1796, in a house at 125 Rue du Bac, now demolished. His family were bourgeois people — his father was a wigmaker and his mother a milliner — and unlike the experience of some of his artistic colleagues, throughout his life he never felt the want of money, as his parents made good investments and ran their businesses well. After his parents married, they bought the millinery shop where she had worked and he gave up his career as a wigmaker to run the business side of the shop. The store was a famous destination for fashionable Parisians and earned the family an excellent income. Corot was the middle of three children born to the family, who lived above their shop during those years.

Corot received a scholarship to study in Rouen, but left after having scholastic difficulties and entered a boarding school. He “was not a brilliant student, and throughout his entire school career he did not get a single nomination for a prize, not even for the drawing classes.” Unlike many masters who demonstrated early talent and inclinations toward art, before 1815 Corot showed no such interest. During those years he lived with the Sennegon family, whose patriarch was a friend of Corot’s father and who spent much time with young Corot on nature walks. It was in this region that Corot made his first paintings after nature. At nineteen, Corot was a “big child, shy and awkward. He blushed when spoken to. Before the beautiful ladies who frequented his mother’s salon, he was embarrassed and fled like a wild thing… Emotionally, he was an affectionate and well-behaved son, who adored his mother and trembled when his father spoke.” When Corot’s parents moved into a new residence in 1817, the twenty-one year old Corot moved into the dormer-windowed room on the third floor, which became his first studio as well.

With his father’s help he apprenticed to a draper, but he hated commercial life and despised what he called "business tricks”, yet he faithfully remained in the trade until he was 26, when his father consented to his adopting the profession of art. Later Corot stated, “I told my father that business and I were simply incompatible, and that I was getting a divorce.” The business experience proved beneficial, however, by helping him develop an aesthetic sense through his exposure to the colors and textures of the fabrics. Perhaps out of boredom, he turned to oil painting around 1821 and began immediately with landscapes. Starting in 1822 after the death of his sister, Corot began receiving a yearly allowance of 1500 francs which adequately financed his new career, studio, materials, and travel for the rest of his life. He immediately rented a studio on quai Voltaire.

During the period when Corot acquired the means to devote himself to art, landscape painting was on the upswing and generally divided into two camps: one ― historical landscape by Neoclassicists in Southern Europe representing idealized views of real and fancied sites peopled with ancient, mythological, and biblical figures; and two ― realistic landscape, more common in Northern Europe, which was largely faithful to actual topography, architecture, and flora, and which often showed figures of peasants. In both approaches, landscape artists would typically begin with outdoor sketching and preliminary painting, with finishing work done indoors. Highly influential upon French landscape artists in the early 19th century was the work of Englishmen John Constable and J.M.W. Turner, who reinforced the trend in favor of Realism and away from Neoclassicism.

For a short period between 1821–1822, Corot studied with Achille-Etna Michallon, a landscape painter of Corot’s age who was a protégé of the painter David and who was already a well-respected teacher. Michallon had a great influence on Corot’s career. Corot’s drawing lessons included tracing lithographs, copying three-dimensional forms, and making landscape sketches and paintings outdoors, especially in the forests of Fontainebleau, the seaports along Normandy, and the villages west of Paris such as Ville-d’Avray (where his parents had a country house). Michallon also exposed him to the principles of the French Neoclassic tradition, as espoused in the famous treatise of theorist Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes, and exemplified in the works of French Neoclassicists Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin, whose major aim was the representation of ideal Beauty in nature, linked with events in ancient times.

Though this school was on the decline, it still held sway in the Salon,

the foremost art exhibition in France attended by thousands at each

event. Corot later stated, “I made my first landscape from nature…under

the eye of this painter, whose only advice was to render with the

greatest scrupulousness everything I saw before me. The lesson worked;

since then I have always treasured precision.” After Michallon’s early death in 1822, Corot studied with Michallon’s teacher, Jean-Victor Bertin, among the best known Neoclassic landscape painters in France, who had Corot draw copies of lithographs of

botanical subjects to learn precise organic forms. Though holding

Neoclassicists in the highest regard, Corot did not limit his training

to their tradition of allegory set in imagined nature. His notebooks

reveal precise renderings of tree trunks, rocks, and plants which show

the influence of Northern realism. Throughout his career, Corot

demonstrated an inclination to apply both traditions in his work,

sometimes combining the two. With

his parents' support, Corot followed the well-established pattern of

French painters who went to Italy to study the masters of the Italian

Renaissance and to draw the crumbling monuments of Roman antiquity. A

condition by his parents before leaving was that he paint a

self-portrait for them, his first. Corot’s stay in Italy from 1825 to

1828 was a highly formative and productive one, during which he

completed over 200 drawings and 150 paintings. He

worked and traveled with several young French painters also studying

abroad who painted together and socialized at night in the cafes,

critiquing each other and gossiping. Corot learned little from the

Renaissance masters (though later he cited Leonardo da Vinci as his favorite painter) and spent most of his time around Rome and in the Italian countryside. The Farnese Gardens with its splendid views of the ancient ruins was a frequent destination, and he painted it at three different times of the day. The

training was particularly valuable in gaining an understanding of the

challenges of both the mid-range and panoramic perspective, and in

effectively placing man-made structures in a natural setting. He

also learned how to give buildings and rocks the effect of volume and

solidity with proper light and shadow, while using a smooth and thin

technique. Furthermore, placing suitable figures in a secular setting

was a necessity of good landscape painting, to add human context and

scale, and it was even more important in allegorical landscapes. To

that end Corot worked on figure studies in native costume as well as

nude. During winter, he spent time in a studio but returned to work outside as quickly as weather permitted. The

intense light of Italy posed considerable challenges, “This sun gives

off a light that makes me despair. It makes me feel the utter

powerlessness of my palette.” He learned to master the light and to paint the stones and sky in subtle and dramatic variation. It

was not only Italian architecture and light which captured Corot’s

attention. The late-blooming Corot was entranced with Italian females

as well, “They still have the most beautiful women in the world that I

have met….their eyes, their shoulders, their hands are spectacular. In

that, they surpass our women, but on the other hand, they are not their

equals in grace and kindness…Myself, as a painter I prefer the Italian

woman, but I lean toward the French woman when it comes to emotion.” In

spite of his strong attraction to women, he writes of his commitment to

painting, “I have only one goal in life that I want to pursue

faithfully: to make landscapes. This firm resolution keeps me from a

serious attachment. That is to say, in marriage…but my independent

nature and my great need for serious study make me take the matter

lightly.” During

the six-year period following his first Italian visit and his second,

Corot focused on preparing large landscapes for presentation at the Salon.

Several of his salon paintings were adaptations of his Italian oil

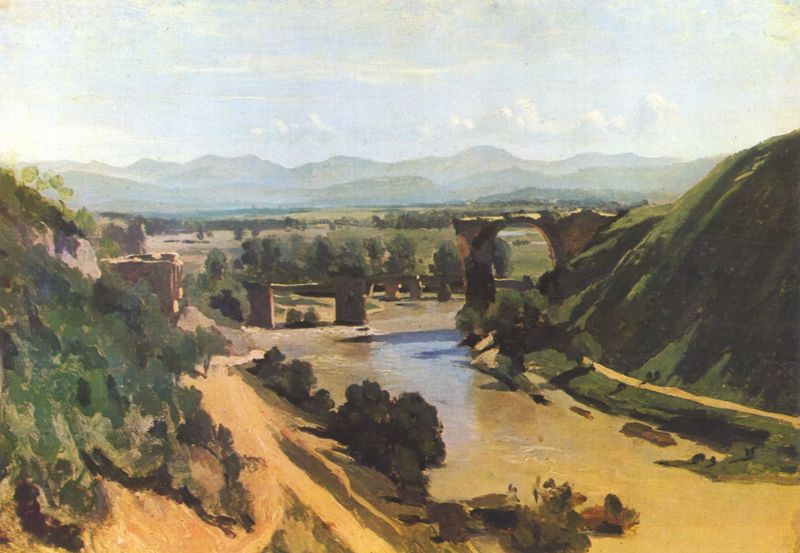

sketches reworked in the studio by adding imagined, formal elements consistent with Neoclassical principles. An example of this was his first Salon entry, View at Narni (1827),

where he took his quick, natural study of a ruin of a Roman aqueduct in

dusty bright sun and transformed it into a falsely idyllic pastoral

setting with giant shade trees and green lawns, a conversion meant to

appeal to the Neoclassical jurors. Many

critics have valued highly his plein-air Italian paintings for their

“germ of Impressionism”, their faithfulness to natural light, and their

avoidance of academic values, even though they were intended as studies. Several decades later, Impressionism revolutionized

art by a taking a similar approach — quick, spontaneous painting done in

the out-of-doors; however, where the Impressionists used rapidly

applied, un-mixed colors to capture light and mood, Corot usually mixed

and blended his colors to get his dreamy effects. When

out of the studio, Corot traveled throughout France, mirroring his

Italian methods, and concentrated on rustic landscapes. He returned to

the Normandy coast and to Rouen, the city he lived in as a youth. Corot

also did some portraits of friends and relatives, and received his

first commissions. His sensitive portrait of his niece, Laure Sennegon,

dressed in powder blue, was one of his most successful and was later

donated to the Louvre. He

typically painted two copies of each family portrait, one for the

subject and one for the family, and often made copies of his landscapes

as well. Corot exhibited one portrait and several landscapes at the Salon in 1831 and 1833. His

reception by the critics at the Salon was cool and Corot decided to

return to Italy, having failed to satisfy them with his Neoclassical themes.

During his two return trips to Italy,

he visited Northern Italy, Venice, and again the Roman countryside. In

1835, Corot created a sensation at the Salon with his biblical painting Agar dans le desert (Hagar

in the Wilderness), which depicted Hagar, Sarah’s handmaiden, and the

child Ishmael, dying of thirst in the desert until saved by an angel.

The background was likely derived from an Italian study. This

time, Corot’s unanticipated bold, fresh statement of the Neoclassical

ideal succeeded with the critics by demonstrating “the harmony between

the setting and the passion or suffering that the painter chooses to

depict in it.” He

followed that up with other biblical and mythological subjects but

those paintings did not succeed as well, as the Salon critics found him

wanting in comparisons with Poussin. In 1837, he painted his earliest surviving nude, The Nymph of the Seine.

Later, he advised his students “The study of the nude, you see, is the

best lesson that a landscape painter can have. If someone knows how,

without any tricks, to get down a figure, he is able to make a

landscape; otherwise he can never do it.” Through

the 1840s, Corot continued to have his troubles with the critics (many

of his works were flatly rejected for salon exhibition) nor were many

works purchased by the public. While recognition and acceptance by the

establishment came slowly, by 1845 Baudelaire led

a charge pronouncing Corot the leader in the “modern school of

landscape painting”. While some critics found Corot’s colors “pale” and

his work having “naive awkwardness”, Baudelaire astutely responded, “M.

Corot is more a harmonist than a colorist, and his compositions, which

are always entirely free of pedantry, are seductive just because of

their simplicity of color.” In 1846, the French government decorated him with the cross of the Légion d' Honneur and in 1848 he was awarded a second-class medal at the Salon, but he received little state patronage as a result. His

only commissioned work was a religious painting for a baptismal chapel

painted in 1847, in the manner of the Renaissance masters. Though the establishment kept holding back, other painters acknowledged Corot’s growing stature. In 1847, Delacroix noted

in his journal, “Corot is a true artist. One has to see a painter in

his own place to get an idea of his worth…Corot delves deeply into a

subject: ideas come to him and he adds while working; it’s the right

approach.” Upon

Delacroix’s recommendation, the painter Constant Dutilleux, bought a

Corot painting and began a long and rewarding relationship with the

artist, bringing him friendship and patrons. Corot’s public treatment dramatically improved after the Revolution of 1848, when he was admitted as a member of the Salon jury. He was promoted to an officer of the Salon in 1867. Having

forsaken any long-term relationships with women, Corot remained very

close to his parents even in his fifties. A contemporary said of him,

“Corot is a man of principle, unconsciously Christian; he surrenders

all his freedom to his mother…he has to beg her repeatedly to get

permission to go out…for dinner every other Friday.” Apart

from his frequent travels, Corot remained closely tethered to his

family until his parents died, then at last he gained the freedom to go

as he pleased. That freedom allowed him to take on students for informal sessions. Future Impressionist Camille Pissarro was briefly among them. Corot’s vigor and perceptive advice impressed his students. Charles Daubigny stated,

“He’s a perfect Old Man Joy, this Father Corot. He is altogether a

wonderful man, who mixes jokes in with his very good advice.” Another

student said of Corot, “the newspapers had so distorted Corot, putting

Theocritus and Virgil in his hands, that I was quite surprised to find

him knowing neither Greek nor Latin…His welcome is very open, very

free, very amusing: he speaks or listens to you while hopping on one

foot or on two; he sings snatches of opera in a very true voice”, but

he has a “shrewd, biting side carefully hidden behind his good nature.” By

the mid-1850s, Corot’s increasingly impressionistic style began to get

the recognition that fixed his place in French art. “M. Corot excels…in

reproducing vegetation in its fresh beginnings; he marvelously renders

the firstlings of the new world.” From the 1850s on, Corot painted many landscape souvenirs and paysages, dreamy imagined paintings of remembered locations from earlier visits painted with lightly and loosely dabbed strokes. In

the 1860s, Corot was still mixing peasant figures with mythological

ones, mixing Neoclassicism with Realism, causing one critic to lament,

“If M. Corot would kill, once and for all, the nymphs of his woods and

replace them with peasants, I should like him beyond measure.” In

reality, in later life his human figures did increase and the nymphs

did decrease, but even the human figures were often set in idyllic

reveries. In

later life, Corot’s studio was filled with students, models, friends,

collectors, and dealers who came and went under the tolerant eye of the

master, causing him to quip, “Why is it that there are ten of you

around me, and not one of you thinks to relight my pipe.” Dealers snapped up his works and his prices were often above 4,000 francs per painting. With

his success secured, Corot gave generously of his money and time. He

became an elder of the artists’ community and would use his influence

to gain commissions for other artists. In 1871 he gave £2000 for

the poor of Paris, under siege by the Prussians. During the actual Paris Commune he was at Arras with Alfred Robaut. In 1872 he bought a house in Auvers as a gift for Honoré Daumier, who by then was blind, without resources, and homeless. In 1875 he donated 10.000 francs to the widow of Millet in

support of her children. His charity was near proverbial. He also

financially supported the upkeep of a day center for children on rue

Vandrezanne in Paris. In later life, he remained a humble and modest

man, apolitical and happy with his luck in life, and held close the

belief that, “men should not puff themselves up with pride, whether

they are emperors adding this or that province to their empires or

painters who gain a reputation.” Despite

great success and appreciation among artists, collectors, and the more

generous critics, his many friends considered, nevertheless, that he

was officially neglected, and in 1874, a short time before his death,

they presented him with a gold medal. He died in Paris of a stomach disorder aged 78 and was buried at Père Lachaise. A number of followers called themselves Corot's pupils. The best known are Camille Pissarro, Eugène Boudin, Berthe Morisot, Stanislas Lépine, Antoine Chintreuil, François-Louis Français, Charles Le Roux, and Alexandre DeFaux.