<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel, 1784

- Painter Edward Hopper, 1882

- King of Castilla y León Philip I, 1478

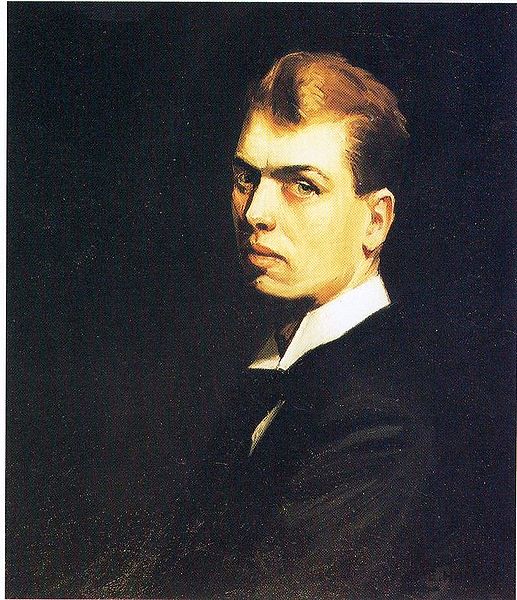

Edward Hopper (July 22, 1882 – May 15, 1967) was a prominent American realist painter and printmaker. While most popularly known for his oil paintings, he was equally proficient as a watercolorist and printmaker in etching. In both his urban and rural scenes, his spare and finely calculated renderings reflected his personal vision of modern American life.

Hopper was born in upper Nyack, New York, a yacht-building center on the Hudson River north of New York City. He was one of two children of a comfortably well-off, middle-class family. His parents, mostly of Dutch ancestry, were Garret Henry Hopper, a dry-goods merchant, and his wife Elizabeth Griffiths Smith. Though not as successful as his forebears, Garrett provided well for his two children with considerable help from his wife’s inheritance. He retired at age forty-nine. Edward and his only sister Marion attended both private and public schools. They were raised in a strict Baptist home. His father had a mild nature, and the household was dominated by women: Hopper's mother, grandmother, sister, and maid. Hopper was a good student in grade school and showed talent in drawing at age five. He readily absorbed his father’s intellectual tendencies and love of French and Russian culture. He also demonstrated his mother’s artistic heritage. Hopper’s parents encouraged his art and kept him amply supplied with materials, instructional magazines, and illustrated books. By his teens, he was working in pen-and-ink, charcoal, watercolor, and oil — drawing from nature as well as making political cartoons. In 1895, he created his first signed oil painting, Rowboat in Rocky Cove. It showed his early interest in nautical subjects. In his early self-portraits, Hopper tended to represent himself as skinny, ungraceful, and homely. Though a tall and quiet teenager, his prankish sense of humor found outlet in his art, sometimes in depictions of immigrants or of women dominating men in comic situations. Later in life, he depicted mostly women as figures in his paintings. In high school, he dreamed of being a naval architect, but after graduation he declared his intention to follow an art career. Hopper’s parents insisted that he study commercial art to have a reliable means of income. In developing his self-image and individualistic philosophy of life, Hopper was influenced by the writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson. He later said, “I admire him greatly…I read him over and over again.”

Hopper began art studies with a correspondence course in 1899. Soon, however, he transferred to the New York Institute of Art and Design. There he studied for six years, with teachers including William Merritt Chase, who instructed him in oil painting. Early on, Hopper modeled his style after Chase and French masters Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas. Sketching from live models proved a challenge and a shock for the conservatively raised Hopper. Another of his teachers, artist Robert Henri, taught life class. Henri encouraged his students to use their art to "make a stir in the world". He also advised his students, “It isn’t the subject that counts but what you feel about it” and “Forget about art and paint pictures of what interests you in life.” In this manner, Henri influenced Hopper, as well as notable future artists George Bellows and Rockwell Kent. He encouraged them to imbue a modern spirit in their work. Some artists in Henri's circle, including John Sloan, became members of “The Eight”, also known as the Ashcan School of American Art. Hopper's first existing oil painting to hint at his famous interiors was Solitary Figure in a Theater (c.1904). During his student years, he also painted dozens of nudes, still lifes, landscapes, and portraits, including his self-portraits.

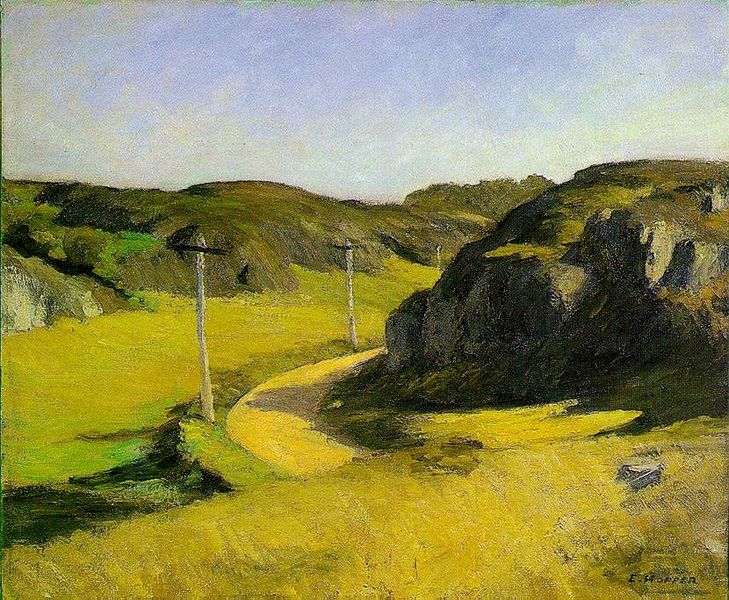

In 1905, Hopper landed a part-time job with an advertising agency, where he did cover designs for trade magazines. Much like famed illustrator N.C. Wyeth, Hopper came to detest illustration. He was bound to it by economic necessity until the mid-1920s. He

temporarily escaped by making three trips to Europe, each centered in

Paris, ostensibly to study the emerging art scene there. In fact,

however, he studied alone and seemed mostly unaffected by the new

currents in art. Later he said that he “didn’t remember having heard of Picasso at all.” He was highly impressed by Rembrandt, particularly his Night Watch, which he said was “the most wonderful thing of his I have seen; it’s past belief in its reality.” Hopper began painting urban and architectural scenes in a dark palette. Then he shifted to the lighter palette of the Impressionists before

returning to the darker palette with which he was comfortable. Hopper

later said, "I got over that and later things done in Paris were more

the kind of things I do now.” Hopper

spent much of his time drawing street and café scenes, and going

to the theater and opera. Unlike many of his contemporaries who

imitated the abstract cubist experiments, Hopper was attracted to realist art. Later, he admitted to no European influences other than French engraver Charles Méryon, whose moody Paris scenes Hopper imitated. After

returning from his last European trip, Hopper rented a studio in New

York City, where he struggled to define his own style. Reluctantly, he

returned to illustration. Being a free-lancer, Hopper was forced to

solicit for projects, and had to knock on the doors of magazine and

agency offices to find business. His

painting languished: “it’s hard for me to decide what I want to paint.

I go for months without finding it sometimes. It comes slowly.” His

fellow illustrator Walter Tittle described Hopper’s depressed emotional

state in sharper terms, seeing his friend “suffering…from long periods

of unconquerable inertia, sitting for days at a time before his easel

in helpless unhappiness, unable to raise a hand to break the spell.” In 1912, Hopper traveled to Gloucester, Massachusetts, to seek some inspiration and did his first outdoor paintings in America. He painted Squam Light, the first of many lighthouse paintings to come. In 1913, at the famous Armory Show, Hopper sold his first painting, Sailing (1911), which he painted over an earlier self-portrait. Hopper

was thirty-one, and though he hoped his first sale would lead to others

in short order, his career would not catch fire for many more years to

come. Shortly after his father’s death that same year, Hopper moved to the Greenwich Village section

of New York City, where he lived for the rest of his life. The

following year he received a commission to make some movie posters and

handle publicity for a movie company. Though

he did not like the illustration work, Hopper was a life-long devotee

of the cinema and the theatre, both of which became subjects for his

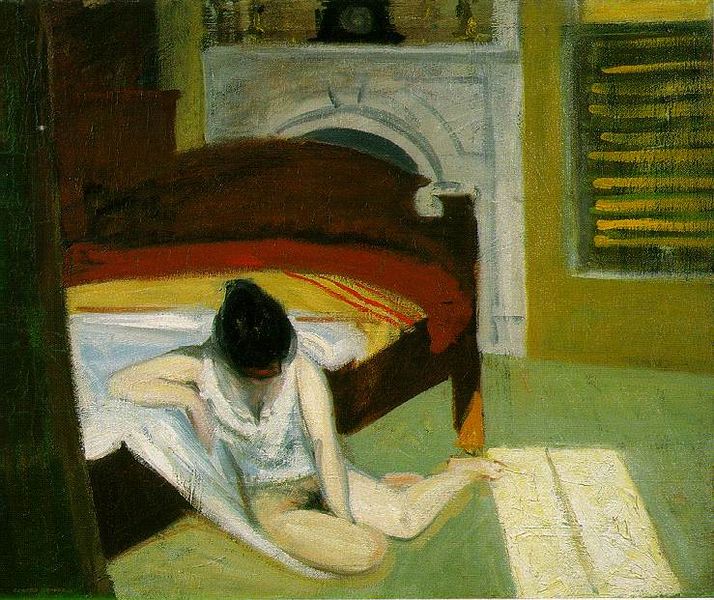

paintings. Each form influenced his compositional methods. At an impasse over his oil paintings, in 1915 Hopper turned to etching, producing about 70 works, many of urban scenes of both Paris and New York. He also produced some posters for the war effort, as well as continuing with occasional commercial projects. When he could, Hopper did some outdoor watercolors on visits to New England, especially at the art colonies at Ogunquit, Maine, and Monhegan Island. His etchings around 1920 began to get public recognition and expressed some of his later themes, as in Night on the El Train (couples in silence), Evening Wind (solitary female), and The Catboat (simple nautical scene). Two notable oil paintings of this time were New York Interior (1921) and New York Restaurant (1922). He also painted two of his many “window” paintings to come: Girl at the Sewing Machine and Moonlight Interior, that show a figure (clothed or nude) near or gazing out a window of an apartment or viewed from the outside looking in. By 1923, Hopper’s slow climb finally produced a breakthrough. He re-encountered his future wife Josephine Nivison, an artist and former student of Robert Henri, during a summer painting trip in Gloucester.

They were opposites: she was short, open, gregarious, sociable, and

liberal, while he was tall, secretive, shy, quiet, introspective, and

conservative. They

married a year later. She remarked famously, “Sometimes talking to

Eddie is just like dropping a stone in a well, except that it doesn’t

thump when it hits bottom.” She

subordinated her career to his and shared his reclusive life style. The

rest of their lives revolved around their spare walk-up apartment in

the city and their summers in South Truro on Cape Cod. She managed his career and his interviews, was his primary model, and was his life companion. With Nivison’s help, six of Hopper’s Gloucester watercolors were admitted to an exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum in 1923. One of them, The Mansard Roof, was purchased by the museum for its permanent collection for the sum of $100. The

critics generally raved about his work; one stated, “What vitality,

force and directness! Observe what can be done with the homeliest

subject.” Hopper sold all his watercolors at a one-man show the following year and finally decided to put illustration behind him. The

artist had demonstrated his ability to transfer his attraction to

Parisian architecture to American urban and rural architecture.

According to Boston Museum of Fine Arts curator Carol Troyen, "Hopper really liked the way these houses, with their turrets and towers and porches and mansard roofs and ornament cast wonderful shadows. He always said that his favorite thing was painting sunlight on the side of a house." At

forty-one, Hopper finally received the recognition he deserved. He

continued to harbor bitterness about his career, later turning down

appearances and awards. His

financial stability now secured, Hopper would live a simple, stable

life and continue creating art in his distinctive style for four more

decades. His Two on the Aisle (1927)

sold for a personal record $1,500, enabling Hopper to purchase an

automobile, which he used to make field trips to remote areas of New

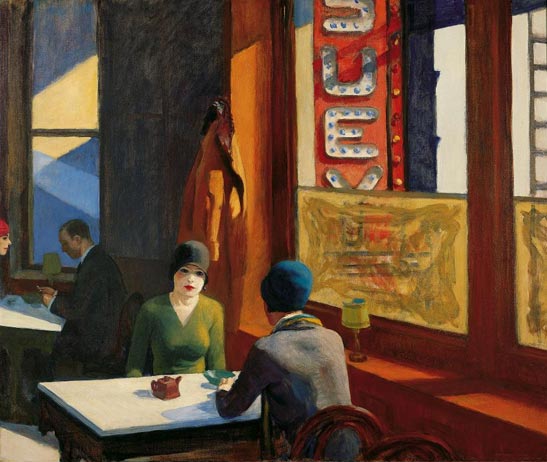

England. In 1929, he produced Chop Suey and Railroad Sunset. The following year, art patron Stephen Clark donated House by the Railroad (1925) to the Museum of Modern Art, the first oil painting it acquired for its collection. Hopper painted his last self-portrait in oil around 1930. Though she posed for

many of his paintings, Jo Hopper modeled for only one oil portrait, Jo Painting (1936). Hopper fared better than many other artists during the Great Depression. His stature took a sharp rise in 1931 when major museums, including the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, paid thousands of dollars for his works. He sold 30 paintings that year, including 13 watercolors. The following year he participated in the first Whitney Annual, and he continued to exhibit in every annual at the museum for the rest of his life. In 1933, the Museum of Modern Art gave Hopper his first large-scale retrospective. The

Hoppers built their summer house in South Truro in 1934. Hopper was

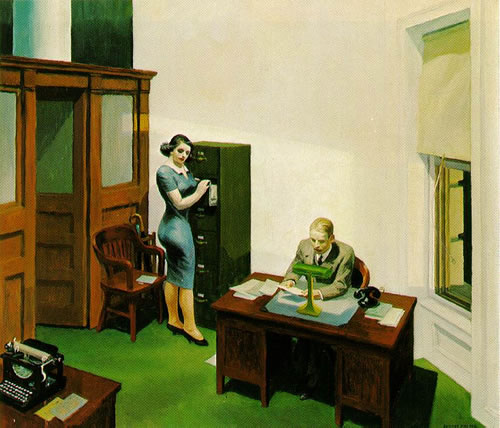

very productive through the 1930s and early 1940s, producing among many

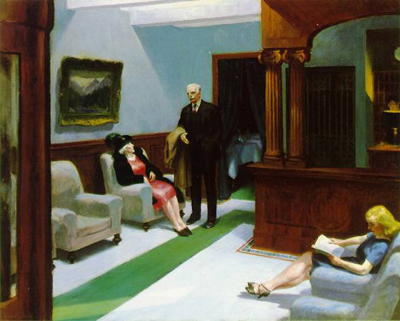

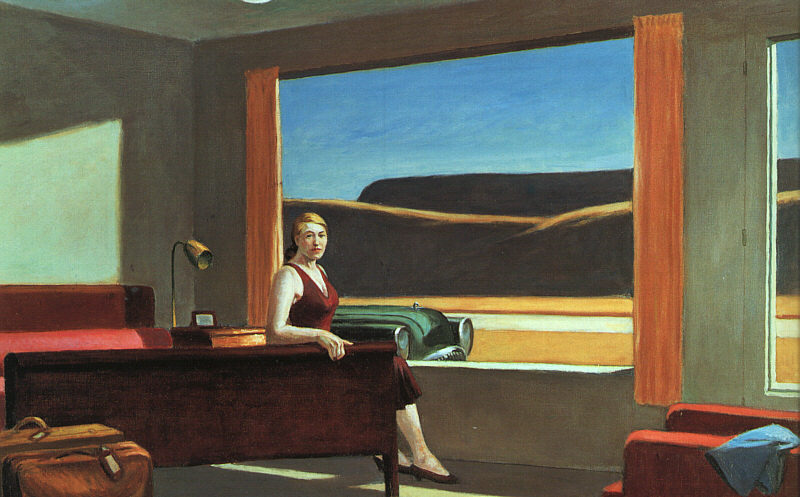

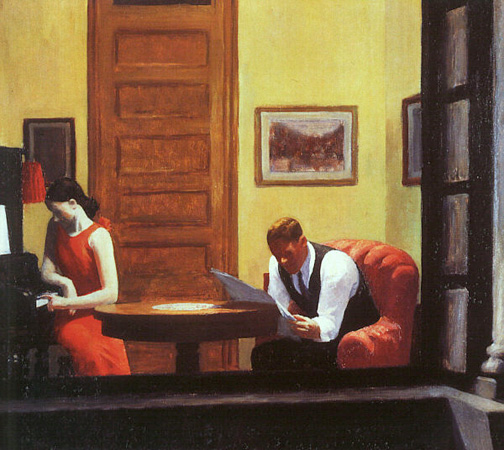

important works New York Movie (1939), Girlie Show (1941), Nighthawks (1942), Hotel Lobby (1943), and Morning in a City (1944).

During the late 1940s, however, he suffered a period of relative

inactivity. He admitted, “I wish I could paint more. I get sick of

reading and going to the movies.” In the two decades to come his health faltered, and he had several prostate surgeries and other medical problems. Nonetheless, in the 1950s and early 1960s, he created several more major works, including First Row Orchestra (1951); as well as Morning Sun and Hotel by a Railroad, both in 1952; and Intermission (1963). Edward Hopper died in his studio near Washington Square in New York City in 1967. His wife, who died 10 months later, bequeathed their joint collection of over three thousand works to the Whitney Museum of American Art. Other significant paintings by Hopper are held by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, The Des Moines Art Center, and the Art Institute of Chicago.