<Back to Index>

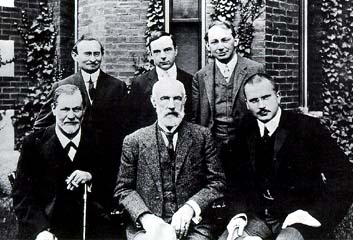

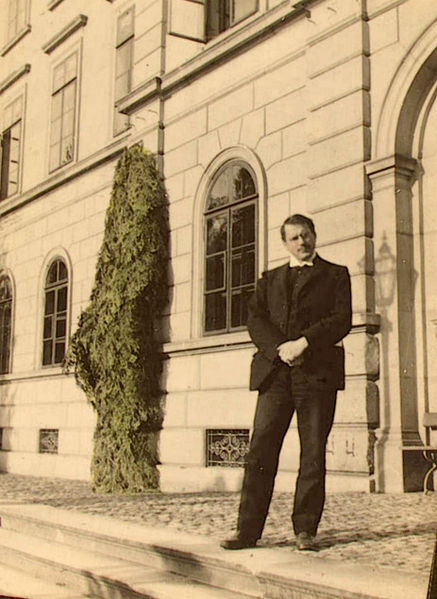

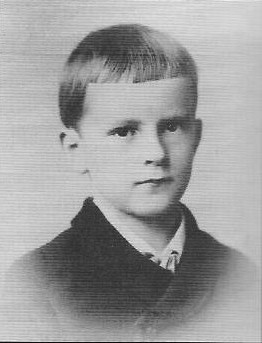

- Psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung, 1875

- Playwright George Bernard Shaw, 1856

- President of Mexico Mariano Arista, 1802

Carl Gustav Jung (26 July 1875 – 6 June 1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist, an influential thinker and the founder of analytical psychology (also known as Jungian psychology). Jung's approach to psychology has been influential in the field of depth psychology and in countercultural movements across the globe. Jung is considered as the first modern psychologist to state that the human psyche is "by nature religious" and to explore it in depth. He emphasized understanding the psyche through exploring the worlds of dreams, art, mythology, religion and philosophy. Though not the first to analyze dreams, he has become perhaps the most well known pioneer in the field of dream analysis. Although he was a theoretical psychologist and practicing clinician, much of his life's work was spent exploring other areas, including Eastern and Western philosophy, alchemy, astrology, sociology, as well as literature and the arts.

Jung emphasized the importance of balance and harmony. He cautioned that modern people rely too heavily on natural science and logical positivism and would benefit from integrating spirituality and appreciation of unconscious realms. He considered the process of individuation necessary for a person to become whole. This is a psychological process of integrating the conscious with the unconscious while still maintaining conscious autonomy. Individuation was the central concept of analytical psychology. Jungian ideas are not typically included in curriculum of most major universities' psychology departments, but are occasionally explored in humanities departments. Many pioneering psychological concepts were originally proposed by Jung, including the Archetype, the Collective Unconscious, the Complex, and synchronicity. A popular psychometric instrument, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), has been principally developed from Jung's theories.

Carl

Jung

was born Karle Gustav II Jung in Kesswil,

the Swiss canton (or county) of Thurgau,

as the fourth but only surviving child of Paul Achilles Jung and Emilie

Preiswerk. His father was a poor rural pastor in the Swiss Reformed

Church while his mother came from a wealthy and established

Swiss family. When

Jung

was six months old his father was appointed to a more prosperous

parish in Laufen.

Meanwhile, the tension between his parents was growing. An eccentric

and depressed woman, Emilie Jung spent much of the time in her own

separate bedroom, enthralled by the spirits that she said visited her

at night. Jung

had a better relationship with his father because he thought him to be

predictable and thought his mother to be very problematic. Although

during the day he also saw her as predictable, at night he felt some

frightening influences from her room. At night his mother became

strange and mysterious. Jung claimed that one night he saw a faintly

luminous and indefinite figure coming from her room, with a head

detached from the neck and floating in the air in front of the body.

His mother left Laufen for several months of hospitalization near Basel for

an unknown physical ailment. Young Carl Jung was taken by his father to

live with Emilie Jung's unmarried sister in Basel, but was later

brought back to the pastor's residence. Emilie's continuing bouts of

absence and often depressed mood influenced her son's attitude towards

women — one of "innate unreliability," a view that he later called the

"handicap I started off with" and that resulted in his

sometimes patriarchal views of women. After

three years of living in Laufen, Paul Jung requested a transfer and was

called to Kleinhüningen in 1879. The relocation brought Emilie

Jung in closer contact to her family and lifted her melancholy and

despondent mood.

A

solitary

and introverted child,

Jung was convinced from childhood that he had two personalities — a

modern Swiss citizen and a personality more at home in the eighteenth

century. "Personality

Number 1," as he termed it, was a typical schoolboy living in the era

of the time, while "Personality Number 2" was a dignified,

authoritative and influential man from the past. Although Jung was

close to both parents he was rather disappointed in his father's

academic approach to faith. A

number of childhood memories had made a life-long impression on him. As

a boy he carved a tiny mannequin into the end of the wooden ruler from

his pupil's pencil case and placed it inside the case. He then added a

stone which he had painted into upper and lower halves and hid the case

in the attic. Periodically he would come back to the mannequin, often

bringing tiny sheets of paper with messages inscribed on them in his

own secret language. This

ceremonial act, he later reflected, brought him a feeling of inner

peace and security. In later years he discovered that similarities

existed in this memory and the totems of native peoples like the

collection of soul-stones near Arlesheim,

or

the tjurungas of

Australia. This, he concluded, was an unconscious ritual that he did

not question or understand at the time, but which was practiced in a

strikingly similar way in faraway locations that he as a young boy had

no way of consciously knowing about. His findings on psychological

archetypes and

the collective unconscious were inspired in part by these experiences. Shortly

before

the

end of his first year at the Humanistisches Gymnasium in

Basel, at age twelve, he was pushed to the ground by another boy so

hard that he was for a moment unconscious (Jung later recognized that

the incident was his fault, indirectly). The thought then came to him

that "now you won't have to go to school any more." From

then on, whenever he started off to school or began homework, he

fainted. He remained at home for the next six months until he overheard

his father speaking worriedly to a visitor of his future ability to

support himself, as they suspected he had epilepsy.

With

little

money in the family, this brought the boy to reality and he

realized the need for academic excellence. He immediately went into his

father's study and began poring over Latin grammar.

He

fainted

three times, but eventually he overcame the urge and did not

faint again. This event, Jung later recalled, "was when I learned what a neurosis is." Jung

had

no

plans to study psychiatry, because it was held in contempt in

those days. But as he started studying his psychiatric textbook, he

became very excited when he read that psychoses are

personality diseases. Immediately he understood this was the field that

interested him the most. It combined both biological and spiritual

facts and this was what he was searching for. In

1895,

Jung studied medicine at the University of

Basel. In 1900, he worked in the Burghölzli,

a

psychiatric hospital in Zürich,

with Eugen Bleuler.

His

dissertation,

published in 1903, was titled "On the Psychology and

Pathology of So-Called Occult Phenomena." In 1906, he published Studies in Word

Association and

later sent a copy of this book to Sigmund Freud,

after

which a close friendship between these two men followed for some

six years. In 1912 Jung published Wandlungen

und

Symbole der Libido (known

in

English as Psychology of

the Unconscious)

resulting in a theoretical divergence between him and Freud and

consequently a break in their friendship, both stating that the other

was unable to admit he could possibly be wrong. After this falling-out,

Jung went through a pivotal and difficult psychological transformation,

which was exacerbated by news of the First World War. Henri

Ellenberger called

Jung's experience a "creative illness" and compared it to Freud's

period of what he called neurasthenia and hysteria. During

World War I Jung was drafted as an army doctor and soon made commandant

of an internment camp for British officers and soldiers. (Swiss

neutrality obliged the Swiss to intern personnel from either side of

the conflict who crossed their frontier to evade capture.) Jung worked

to improve the conditions for these soldiers stranded in neutral

territory; he encouraged them to attend university courses. In 1903,

Jung married Emma

Rauschenbach,

who came from a wealthy family in Switzerland. They had five children:

Agathe, Gret, Franz, Marianne, and Helene. The marriage lasted until

Emma's death in 1955, but he had more-or-less open relationships with

other women. The most well-known women with whom Jung is believed to

have had extramarital relationships were patient and friend Sabina Spielrein and Toni Wolff. Jung

continued to publish books until the end of his life, including Flying Saucers: A Modern

Myth of Things Seen in the Skies, which analyzed the archetypal

meaning and possible psychological significance of the reported

observations of UFOs. He also enjoyed a friendship

with an English Roman Catholic priest, Father Victor White,

who

corresponded with Jung after he had published his controversial Answer to Job.

Jung's

work on himself and his patients convinced him that life has a

spiritual purpose beyond material goals. Our main task, he believed, is

to discover and fulfill our deep innate potential, much as the acorn

contains the potential to become the oak, or the caterpillar to become

the butterfly. Based on his study of Christianity, Hinduism,

Buddhism, Gnosticism, Taoism,

and other traditions, Jung perceived that this journey of

transformation, which he called individuation,

is

at

the mystical heart of all religions. It is a journey to meet the

self and at the same time to meet the Divine. Unlike Sigmund Freud,

Jung thought spiritual experience was essential to our well-being.

In

1944 Jung published “Psychology and Alchemy,” where he analyzed the

alchemical symbols and showed a direct relationship to the

psychoanalytical process. He argued that the alchemical process was the

transformation of the impure soul (lead) to perfected soul (gold), and

a metaphor for the individuation process. Jung died

in 1961 at Küsnacht,

after

a short illness.