<Back to Index>

- Mathematician and Astronomer Johannes Müller von Königsberg (Regiomontanus), 1436

- Painter Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez, 1599

- First President of Indonesia Sukarno, 1901

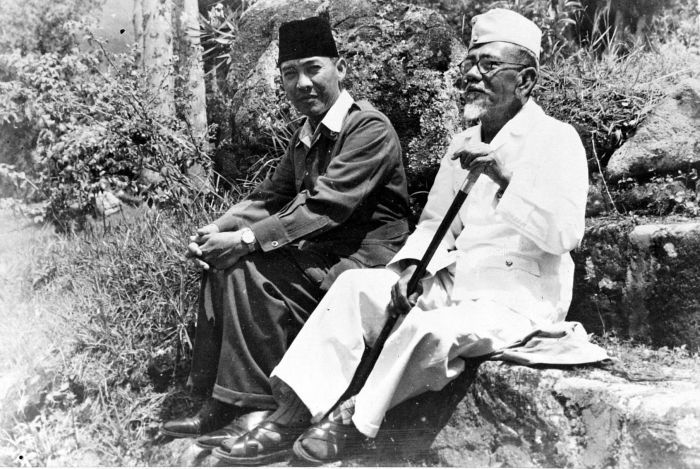

Sukarno, born Kusno Sosrodihardjo (6 June 1901 – 21 June 1970) was the first President of Indonesia. He helped the country win its independence from the Netherlands and was President from 1945 to 1967, presiding with mixed success over the country's turbulent transition to independence. Sukarno was forced out of power by one of his generals, Suharto, who formally became President in March 1967.

The

spelling "Sukarno" is frequently used in English as it is based on the

newer official spelling in Indonesia since 1947 but the older spelling Soekarno is

still frequently used, mainly because he signed his name in the old

spelling. Official Indonesian presidential decrees from the period

1947–1968, however, printed his name using the 1947 spelling. The Soekarno–Hatta International Airport which serves near Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia for example, still uses the older spelling. Indonesians also remember him as Bung Karno or Pak Karno. Like many Javanese people, he had only one name; in religious contexts, he was occasionally referred to as 'Achmed Sukarno'.

The son of a Javanese primary school teacher, an aristocrat named Raden Soekemi Sosrodihardjo and his Balinese wife named Ida Ayu Nyoman Rai from Buleleng regency, Sukarno was born as Kusno Sosrodihardjo in Blitar, East Java in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). Following Javanese custom, he was renamed after surviving a childhood illness. He was admitted into a Dutch-run school as a child. When his father sent him to Surabaya in 1916 to attend a secondary school, he met Tjokroaminoto, a future nationalist. In 1921 he began to study at the Technische Hogeschool (Technical Institute) in Bandung.

He studied civil engineering and focused on architecture. Atypically,

even among the colony's small educated elite, Sukarno was fluent in

several languages. In addition to the Javanese language of his childhood, he was a master of Sundanese, Balinese and of Indonesian, and especially strong in Dutch. He was also quite comfortable in German, English, French, Arabic, and Japanese, all of which were taught at his HBS. He was helped by his photographic memory and precocious mind. In

his studies, Sukarno was "intensely modern," both in architecture and

in politics. Sukarno interpreted these ideas in his dress, in his urban

planning for the capital (eventually Jakarta), and in his socialist politics, though he did not extend his taste for modern art to pop music; he had Koes Plus imprisoned

for their allegedly decadent lyrics despite his reputation for

womanising. For Sukarno, modernity was blind to race, neat and Western

in style, and anti-imperialist.

Sukarno became a leader of a pro-independence party, Partai Nasional Indonesia, when it was founded in 1927. He opposed imperialism and capitalism because he thought both systems worsened the life of Indonesian people. He also hoped that Japan would commence a war against the western powers and that Java could then gain its independence with Japan's aid. He was arrested in 1929 by Dutch colonial authorities and sentenced to two years in prison. By the time he was released, he had become a popular hero. He was arrested several times during the 1930s and was in exile when Japan occupied the archipelago in 1942. In early 1929, during the Indonesian National Revival, Sukarno and fellow Indonesian nationalist leader Mohammad Hatta (later Vice President), first foresaw a Pacific War and the opportunity that a Japanese advance on Indonesia might present for the Indonesian independence cause. In February 1942 Imperial Japan invaded the Dutch East Indies quickly overrunning outmatched Dutch forces who marched, bussed and trucked Sukarno three hundred kilometres to Padang, Sumatra. They intended keeping him prisoner, but abruptly abandoned him to save themselves. The Japanese had their own files on Sukarno and approached him with respect wanting to use him to organise and pacify the Indonesians. Sukarno on the other hand wanted to use the Japanese to free Indonesia: "The Lord be praised, God showed me the way; in that valley of the Ngarai I said: Yes, Independent Indonesia can only be achieved with Dai Nippon...For the first time in all my life, I saw myself in the mirror of Asia." Subsequently, indigenous forces across both Sumatra and Java aided the Japanese against the Dutch but would not cooperate in the supply of the aviation fuel which was essential for the Japanese war effort. Desperate for local support in supplying the volatile cargo, Japan now brought Sukarno back to Jakarta. He helped the Japanese in obtaining its aviation fuel and forced labor conscripts, called kerja paksa in Indonesian and Romusha in Japanese. Sukarno was lastingly ashamed of his role with the romusha. He also was involved with Peta and Heiho (Javanese volunteer army troops) via speeches broadcast on the Japanese radio and loud speaker networks across Java. By mid-1945 these units numbered around two million, and were preparing to defeat any Allied forces sent to re-take Java.

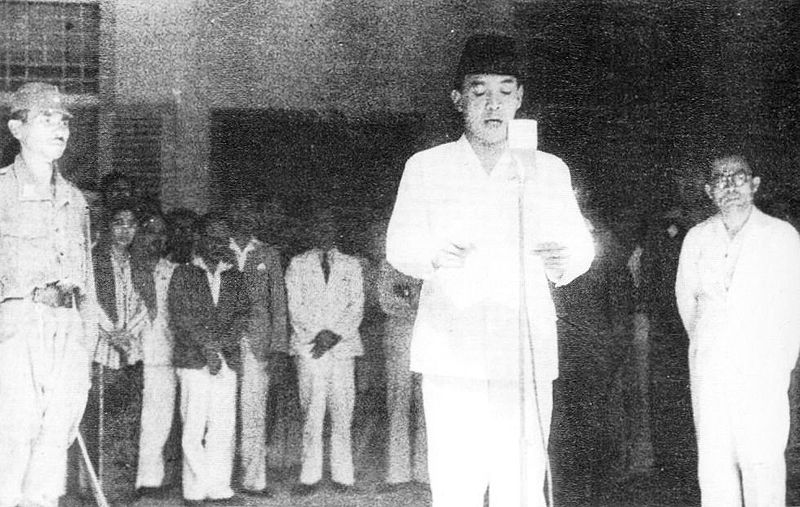

On November 10, 1943 Sukarno was decorated by the Emperor of Japan in Tokyo. He also became head of Badan Penyelidik Usaha Persiapan Kemerdekaan Indonesia (BPUPKI), the Japanese-organized committee through which Indonesian independence was later gained. On 7 September 1944, with the war going badly for the Japanese, Prime Minister Koiso promised independence for Indonesia, although no date was set. This announcement was seen, according to the U.S. official history, as immense vindication for Sukarno's apparent collaboration with the Japanese. The U.S. at the time considered Sukarno one of the "foremost collaborationist leaders." Following the Japanese surrender, Sukarno, Mohammad Hatta, and Dr. Radjiman Wediodiningrat were summoned by Marshal Terauchi, Commander-in-Chief of Japan's Southern Expeditionary Forces in Saigon. Sukarno initially hesitated in declaring Indonesia's independence. He and Mohammad Hatta were kidnapped by Indonesian youth groups to Rengasdengklok, west of Jakarta. Finally Sukarno and Hatta declared the independence of the Republic of Indonesia on August 17, 1945. Sukarno's vision for the 1945 Indonesian constitution comprised the Pancasila (Sanskrit—five principles). Sukarno's political philosophy, Marhaenism, was guided by elements of Marxism, nationalism and Islam. This is reflected in the Pancasila, in the order in which he originally espoused them in a speech on June 1, 1945:

- Nationalism (with a focus on national unity)

- Internationalism ('one nation sovereign amongst equals')

- Representative democracy (all significant groups represented)

- Social Justice (Marxist influenced)

- Theism (with a secular slant)

In the same speech, he argued that all of the principles of the nation could be summarized in the phrase gotong royong. The Indonesian parliament, founded on the basis of this original (and subsequently revised) constitution, proved all but ungovernable. This was due to irreconcilable differences between various social, political, religious and ethnic factions. Sukarno's government initially postponed the formation of a national army, for fear of antagonizing the Allied occupation forces and their doubt over whether they would have been able to form an adequate military apparatus to maintain control of seized territory. The various militia groups at that time were encouraged to join the BKR — Badan Keamanan Rakyat (The People's Security Organization) — itself a subordinate of the "War Victims Assistance Organization". It was only in October 1945 that the BKR was reformed into the TKR — Tentara Keamanan Rakyat (The People's Security Army) in response to the increasing Dutch presence in Indonesia. In the ensuing chaos between various factions and Dutch attempts to re-establish colonial control, Dutch troops captured Sukarno in December 1948, but were forced to release him after the ceasefire. He returned to Jakarta in December 28, 1949. At this time, Indonesia adopted a new federal constitution that made the country a federal state. This was replaced by another provisional constitution in 1950 that restored a unitary form of government. Both constitutions were parliamentary in nature, which limited presidential power. However, even with his formally reduced role, he commanded a good deal of moral authority as Father of the Nation.

Sukarno's

government was not universally accepted in Indonesia. Indeed, many

factions and regions attempted to separate themselves from his

government, and there were several internal conflicts even during the

period of armed insurgency against the Dutch. One such example is the leftist-backed coup attempt by elements of the military in Madiun, East Java in 1948, in which many supporters of communism were allegedly executed. There were further attempts of military coups against Sukarno in 1956, including the PRRI–Permesta rebellion in Sulawesi supported by the CIA, during which an American aviator, Allen Lawrence Pope, operating in support of the rebels was shot down and captured.

Sukarno resented his figurehead position and used the increasing disorder to intervene more in the country's political life. Claiming Western-style democracy was unsuitable for Indonesia, he called for a system of "guided democracy" based on what he called traditional Indonesian principles. The Indonesian way of deciding important questions, he argued, was by way of prolonged deliberation designed to achieve a consensus. He proposed a government based not only on political parties but on "functional groups" composed of the nation's basic elements, in which a national consensus could express itself under presidential guidance. During this later part of his presidency, Sukarno came to increasingly rely on the army and the support of the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI).

In the 1950s he increased his ties to the People's Republic of China and admitted more Communists into his government. He also began to accept increasing amounts of Soviet bloc military aid. This aid, however, was surpassed by military aid from the Eisenhower Administration, which worried about a leftward drift should Sukarno rely too much on Soviet bloc aid. However, Sukarno increasingly attempted to forge a new alliance called the "New Emerging Forces", as a counter to the old superpowers, whom he accused of spreading "Neo-Colonialism, Colonialism and Imperialism" (NEKOLIM). His political alliances gradually shifted towards Asian powers such as the PRC and North Korea. In 1961, this first president of Indonesia also found another political alliance, an organization, called the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM, in Indonesia known as Gerakan Non-Blok, GNB) with Egypt's President Gamal Abdel Nasser, India's Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Yugoslavia's President Josip Broz Tito, and Ghana's President Kwame Nkrumah, in an action called The Initiative of Five (Sukarno, Nkrumah, Nasser, Tito, and Nehru). This action was a movement to not give any favour to the two superpower blocs, who were involved in the Cold War. The Bandung Conference was held in 1955, with the goal of uniting developing Asian and African countries into a non-aligned movement to counter against the competing superpowers at the time. In order to increase Indonesia's prestige, Sukarno supported and won the bid for the 1962 Asian Games held in Jakarta. Many sporting facilities such as the Senayan sports complex (now Bung Karno Stadium), and supporting infrastructure were built to accommodate the games. There was political tension when the Indonesians refused the entry of delegations from Israel and Taiwan.

On November 30, 1957, an assassination attempt was made by a grenade attack against Sukarno when he was visiting a school in Cikini, Central Jakarta. Six children were killed, but Sukarno did not suffer any serious wounds. The perpetrators were members of the Darul Islam rebellious group, under the order of its leader Sekarmadji Maridjan Kartosuwirjo. In December he ordered the nationalization of 246 Dutch businesses. In February he began a crackdown on the PRRI rebels at Bukittinggi. These PRRI rebels, a mix of anti-communist and Islamic movements, received arms and aid from Western sources, including the CIA, until J. Allan Pope, an American pilot, was shot down after a bombing raid in northern Indonesia in 1958. The CIA sent arms to rebel movements on Sumatra as well as Sulawesi. The downing of this pilot, together with impressive victories of government forces against the PRRI, evoked a shift in US policy, leading to closer ties with Sukarno as well as Major General Abdul Haris Nasution, the head of the army and the most powerful anti-communist in the Jakarta government.

Sukarno

also established government control over media and book publishing as

well as laws discriminating against Chinese permanent residents (China

Totok). On July 5, 1959 he reestablished the 1945 constitution by presidential edict.

It established a presidential system which he believed would make it

easier to implement the principles of guided democracy. He called the

system Manifesto Politik or

Manipol — but was actually government by decree. He sent his opponents

to internal exile. In March 1960 Sukarno dissolved the elected Assembly

(Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat)

and replaced it with an appointed Assembly — the Gotong Royong

Parliament. In August Sukarno broke off diplomatic relations with the

Netherlands over Dutch New Guinea (West Papua.) After West Papua declared itself independent in December 1961, Sukarno ordered raids on West Irian (Dutch New Guinea). There were more assassination attempts when he visited Sulawesi in

1962. West Irian was brought under Indonesian authority in May 1963

under the Bunker Plan. In July of the same year People's Consultative

Assembly (Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat) proclaimed Sukarno as President for Life. Sukarno also opposed the British-supported Federation of Malaysia,

claiming that it was a neocolonial plot to advance British interests.

In spite of his political overtures, which was partly justified when

some political elements in British Borneo territories Sarawak and Brunei opposed the Federation plan and aligned themselves with Sukarno, Malaysia was proclaimed in September 1963. This led to the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation (Konfrontasi)

and the end of remaining US military aid to Indonesia. Sukarno withdrew

Indonesia from the UN membership in 1965 when, with US backing, the

nascent Federation of Malaysia took a seat of UN Security Council.

Sukarno's increasing illness was demonstrated when he collapsed in

public in August 9, 1965, and he was secretly diagnosed with kidney

disease.

On the night of 30 September 1965, six of Indonesia's most senior generals were killed by a movement calling themselves the "30 September Movement" (G30S) which claimed to be in control of the government. Major General Suharto, commander of the Army's strategic reserves, took control of the army the following morning. Suharto issued an ultimatum to the Halim Air Force Base, where the G30S had based themselves and where Sukarno (the reasons for his presence are unclear and were subject of claim and counter-claim), Air Marshal Omar Dhani and Aidit had gathered. By the following day, it was clear that the incompetently organised and poorly coordinated coup had failed. By 2 October, Suharto's faction was firmly in control of the army. Sukarno's obedience to Suharto's 1 October ultimatum to leave Halim is seen as changing all power relationships. Sukarno's fragile balance of power between the military, political Islam, communists, and nationalists that underlay his "Guided Democracy" was now collapsing. In early October, a military propaganda campaign began to sweep the country, successfully convincing both Indonesian and international audiences that it was a Communist coup, and that the murders were cowardly atrocities against Indonesian heroes. The PKI's denials of involvement had little effect. The army led a campaign to purge Indonesian society, government and armed forces of the communist party and other leftist organisations. Leading PKI members were immediately arrested, some summarily executed. The purge quickly spread from Jakarta to the rest of the country, and the worst massacres were in Java and Bali. The situation varied across the country; in some areas the army organised civilian groups and local militias, in other areas communal vigilante action preceded the army. The most widely accepted estimates are that at least half a million were killed. Many others were also imprisoned and for the next ten years people were still being imprisoned as suspects. It is thought that as many as 1.5m were imprisoned at one stage or another. As a result of the purge, one of Sukarno's three pillars of support, the Indonesian Communist Party, had been effectively eliminated by the other two, the military and political Islam, although of the two, the military were in the position of unchallenged power. The killings and the failure of his tenuous "revolution" distressed Sukarno and he tried unsuccessfully to maintain his influence appealing in a January 1966 broadcast for the country to follow him. Subandrio sought to create a Sukarnoist column (Barisan Sukarno), which was undermined by Suharto's pledge of loyalty to Sukarno and the concurrent instruction for all those loyal to Sukarno to announce their support for the army. In February, Sukarno reshuffled his cabinet, sacking Nasution as Defence Minister and abolishing his position of armed forces chief of staff, but Nasution refused to step down. On March 11, 1966, Suharto and his supporters in the military forced Sukarno to issue a Presidential Order called Supersemar (Surat Perintah Sebelas Maret — The March 11 Order), in which Sukarno gave orders to Suharto only to restore peace and order, not to transfer of power to him. After obtaining the Presidential Order, Suharto had the PKI declared illegal and the party was abolished. He also arrested many high ranking officials that were loyal to Sukarno on the charge of being PKI members and/or sympathizers, further reducing Sukarno's political power and influence. Sukarno was stripped of his presidential title by Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat Sementara (Provisional Peoples Representative Assembly) on March 12, 1967, led by his former ally, Nasution, and remained under house arrest until his death at age 69 in Jakarta in 1970. He was buried in Blitar, East Java, Indonesia. In recent decades, his grave has been a significant venue in the network of places that Javanese visit on ziarah and for some is of equal significance to those of the Wali Songo.

While

the semi-official version of the events of 1965–1966 claims that the

Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) ordered the murders of the six

generals, others blame Sukarno, and still others believe Suharto

orchestrated the assassinations to remove potential rivals for the

presidency.

Sukarno married Siti Utari circa 1920, and divorced her to marry Inggit Garnasih, who he divorced circa 1931 to marry Fatmawati. Without divorcing, Sukarno also married Hartini, and circa 1959 Dewi Sukarno. Other wives included Oetari, Kartini Manoppo, Ratna Sari, Haryati, Yurike Sanger, and Heldy Djafar. Megawati Sukarnoputri, who served as the fifth president of Indonesia, is his daughter by his wife Fatmawati.