<Back to Index>

- Ornithologist Hermann Schlegel, 1804

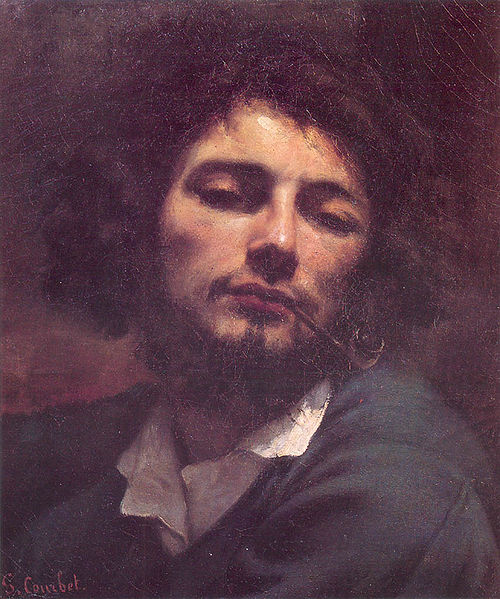

- Painter Jean Désiré Gustave Courbet, 1819

- Prince James Francis Edward Stuart, 1688

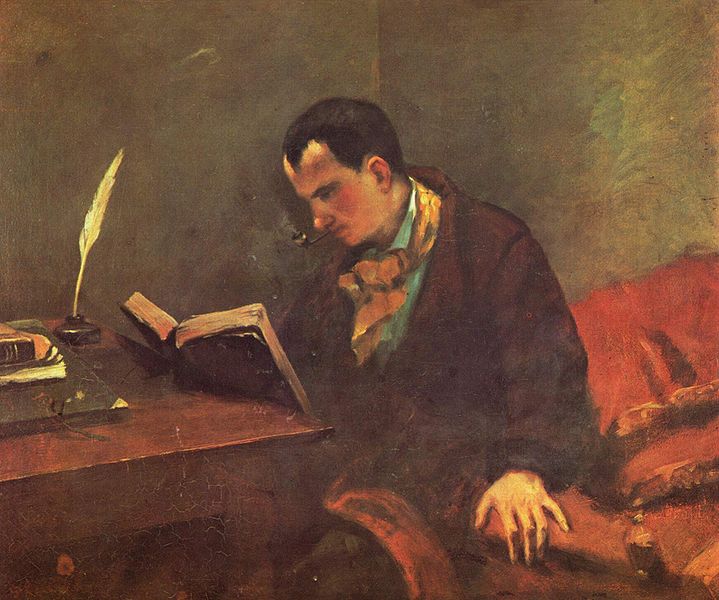

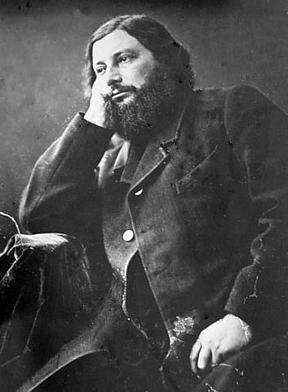

Jean Désiré Gustave Courbet (10 June 1819 – 31 December 1877) was a French painter who led the Realist movement in 19th-century French painting. The Realist movement bridged the Romantic movement (characterized by the paintings of Théodore Géricault and Eugène Delacroix), with the Barbizon School and the Impressionists. Courbet occupies an important place in 19th century French painting as an innovator and as an artist willing to make bold social commentary in his work.

Courbet was a painter of figurative compositions, landscapes, seascapes, and still-lifes.

He courted controversy by addressing social issues in his work, and by

painting subjects that were considered vulgar: the rural bourgeoisie

and peasantry, and the working conditions of the poor. His work

belonged neither to the predominant Romantic nor Neoclassical schools. History painting, which the Paris Salon esteemed

as a painter's highest calling, did not interest Courbet, who stated

that "the artists of one century [are] basically incapable of

reproducing the aspect of a past or future century ..." Instead, he believed that the only possible source for a living art is the artist's own experience. His work, along with the work of Honoré Daumier and Jean-François Millet, became known as Realism.

For Courbet realism dealt not with the perfection of line and form, but

entailed spontaneous and rough handling of paint, suggesting direct

observation by the artist while portraying the irregularities in nature. He depicted the harshness in life, and in so doing, challenged contemporary academic ideas of art. Courbet was born in 1819 to Régis and Sylvie Oudot Courbet in Ornans (Doubs).

Though a prosperous farming family, anti-monarchical feelings prevailed

in the household. (His maternal grandfather fought in the French Revolution.)

Courbet's sisters, Zoé, Zélie and Juliette, were his

first models for drawing and painting. After moving to Paris he

returned home to Ornans often to hunt, fish and find inspiration. He went to Paris in

1839, and worked at the studio of Steuben and Hesse. An independent

spirit, he soon left, preferring to develop his own style by studying

Spanish, Flemish and French painters and painting copies of their work. His first works were an Odalisque, suggested by the writing of Victor Hugo, and a Lélia, illustrating George Sand, but he soon abandoned literary influences for the study of real life. Among his paintings of the early 1840s are several self-portraits, Romantic in conception, in which the artist portrayed himself in various roles. These include the Self-Portrait with Black Dog (c. 1842–1844, accepted for exhibition at the Paris Salon of 1844), the theatrical Self-Portrait, also known as Desperate Man (c. 1843–45), Lovers in the Countryside (1844, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon), The Sculptor (1845), The Wounded Man (1844–1854, Musée d'Orsay, Paris), The Cellist, Self-Portrait (1847, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, shown at the Salon of 1848), and The Man with a Pipe (c. 1848–1849, Musée d'Orsay, Paris). Trips

to the Netherlands and Belgium in 1846–1847 strengthened Courbet's

belief that painters should portray the life around them, as Rembrandt, Hals, and the other Dutch masters had done. By 1848, he had gained supporters among the younger critics, the Neo-romantics and Realists, notably Champfleury. Courbet achieved greater recognition after the success of his painting After Dinner at Ornans at the Salon of 1849. This work, reminiscent of Chardin and Le Nain, earned Courbet a gold medal and was purchased by the state. The gold medal meant that his works would no longer require jury approval for exhibition at the Salon (an exemption Courbet enjoyed until 1857, when this rule was changed). In 1849 Courbet painted Stone-Breakers (destroyed in the British bombing of Dresden in 1945), which was admired by Proudhon as an icon of peasant life, and has been called "the first of his great works". Courbet

was inspired by a scene witnessed on the roadside, as he explained to

Champfleury and the writer Francis Wey: "It is not often that one

encounters so complete an expression of poverty and so, right then and

there I got the idea for a painting. I told them to come to my studio

the next morning." The Salon of 1850–1851 found him triumphant with Stone-Breakers, the Peasants of Flagey, and A Burial at Ornans. The Burial,

one of Courbet's most important works, records an event — the funeral of

his grand uncle — which he witnessed in September 1848. People who had

attended the funeral were used as models for the painting. Previously,

models had been used as actors in historical narratives; here Courbet

said that he "painted the very people who had been present at the

interment, all the townspeople". The result is a realistic presentation

of them, and of life, in Ornans. The

painting, which drew both praise and fierce denunciations from critics

and the public, is an enormous work, measuring 10 by 22 feet (3.1 by

6.6 meters), depicting a prosaic ritual on a scale which previously

would have been reserved for a religious or royal subject. According to

art historian Sarah Faunce, "In Paris the Burial was

judged as a work that had thrust itself into the grand tradition of

history painting, like an upstart in dirty boots crashing a genteel

party, and in terms of that tradition it was of course found wanting." Then too, the painting lacks the sentimental rhetoric that was expected in a genre work:

Courbet's mourners make no theatrical gestures of grief, and their

faces seemed more caricatured than ennobled. The critics accused

Courbet of a deliberate pursuit of ugliness. Eventually

the public grew more interested in the new Realist approach, and the

lavish, decadent fantasy of Romanticism lost popularity. The artist

well understood the importance of this painting; as Courbet said: "The Burial at Ornans was in reality the burial of Romanticism." Courbet became a celebrity, and was spoken of as a genius, a "terrible socialist", and a "savage". He

actively encouraged the public perception of him as an unschooled

peasant, while his ambition, his bold pronouncements to journalists,

and his insistence on depicting his own life in his art gave him a

reputation for unbridled vanity. Courbet associated his ideas of realism in art with anarchism,

and, having gained an audience, he promoted democratic and socialist

ideas by writing politically motivated essays and dissertations. His

familiar visage was the object of frequent caricature in the popular

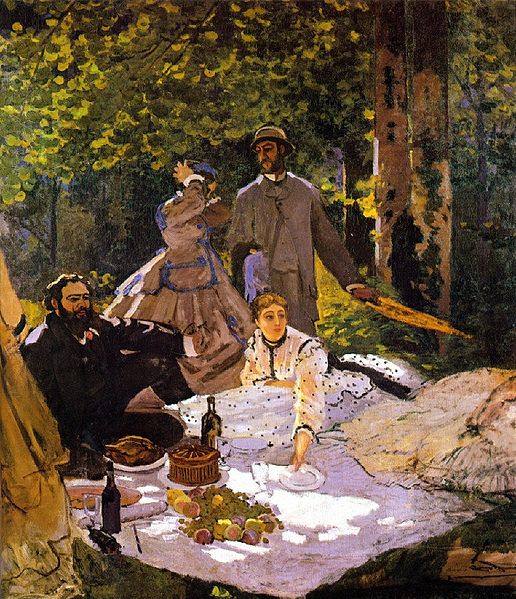

French press. During the 1850s Courbet painted numerous other figurative works using common folk and friends as his subjects, such as Village Damsels (1852), the Wrestlers (1853), Bathers (1853), The Sleeping Spinner (1853), and The Wheat Sifters (1854). In 1855, Courbet submitted fourteen paintings for exhibition at the Exposition Universelle. Three were rejected for lack of space, including A Burial at Ornans and his other monumental canvas The Artist's Studio. Refusing to be denied, Courbet took matters into his own hands: he displayed forty of his paintings, including The Artist's Studio, in his own adjacent gallery called The Pavillion of Realism, which was a temporary structure he erected next door to the official Salon like Exposition Universelle. Although artists like Eugène Delacroix were

ardent champions of his effort, the public came mostly out of curiosity

and to deride him. Attendance and sales were disappointing, but Courbet's status as a hero to the French avant-garde became assured. He was admired by the American James McNeill Whistler, and he became an inspiration to the younger generation of French artists including Édouard Manet and the Impressionist painters

many of whom were still in art school at the time. The painting itself

was recognized as a masterpiece by Delacroix, Baudelaire, and

Champfleury. It is an allegory of his life as a painter, seen as an

heroic venture, in which he is flanked by friends and admirers on the

right, and challenges and opposition to the left. Friends on the right

include the art critics Champfleury, and Charles Baudelaire, and art collector Alfred Bruyas.

On the left are figures (a priest, a prostitute, a grave digger, a

merchant, and others) who represent what Courbet described in a letter

to Champfleury as "the other world of trivial life, the people, misery,

poverty, wealth, the exploited and the exploiters, the people who live

off death." In the Salon of 1857 Courbet showed six paintings. These included the scandalousYoung Ladies on the Banks of the Seine (Summer), depicting two prostitutes under a tree, as well as the first of many

hunting scenes Courbet was to paint during the remainder of his life: Hind at Bay in the Snow and The Quarry. By exhibiting sensational works alongside hunting scenes of the sort that had brought popular success to the English painter Edwin Landseer, Courbet guaranteed himself "both notoriety and sales". During the 1860s, Courbet painted a series of increasingly erotic works such as Femme nue couchée. This culminated in The Origin of the World (L'Origine du monde) (1866), which depicts female genitalia and was not publicly exhibited until 1988, and Sleep (1866),

featuring two women in bed. The latter painting became the subject of a

police report when it was exhibited by a picture dealer in 1872. By

the 1870s Courbet had become well established as one of the leading

artists in France. On 14 April 1870, Courbet established a "Federation of Artists" (Fédération des artistes) for the free and uncensored expansion of art. The group's members included André Gill, Honoré Daumier, Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, Eugène Pottier, Jules Dalou, and Édouard Manet.

Until about 1861, Napoléon's regime exhibited authoritarian

characteristics, using press censorship to prevent the spread of

opposition, manipulating elections, and depriving the Parliament of the

right to free debate or any real power. In the decade of the 1860s,

however, Napoléon III made

more concessions to placate his liberal opponents. This change began by

allowing free debates in Parliament and public reports of parliamentary

debates, continued with the relaxation of press censorship, and

culminated in the appointment of the Liberal Émile Ollivier,

previously a leader of the opposition to Napoléon's regime, as

(effectively) Prime Minister in 1870. As a sign of appeasement to the

Liberals who admired Courbet, Napoleon III nominated him to the Legion of Honour in 1870. His refusal of the cross of the Legion of Honour offered

to him by Napoleon III angered those in power but made him immensely

popular with those who opposed the current regime, and in 1871 under

the revolutionary Paris Commune he

was placed in charge of all the Paris art museums and saved them from

looting mobs. However when the power shifted back to the old guard

Courbet found himself in an untenable political position. During the Paris Commune in 1871, Courbet proposed that the Vendôme column be disassembled and re-erected in the Hôtel des Invalides.

This

project was not adopted, but, on April 12, 1871, the dismantling of the

imperial symbol was voted, and the column taken down on May 8, with no

intentions of rebuilding it. The bronze plates were preserved. For his

insistence in executing the Communal decree for the destruction of the Vendôme Column, he was designated as responsible for the act and accordingly sentenced

on 2 September 1871 by a Versailles court martial to six months in

prison and a fine of 500 francs. During his incarceration, Courbet

painted several still-life compositions. In 1872 he depicted his

imprisonment in the Self-Portrait at Ste.-Pélagie. After the assault on the Paris Commune by Adolphe Thiers,

head of the new provisional national government, the decision was taken

to rebuild the column with its statue of Napoléon. In 1873, the

newly elected president Mac-Mahon wanted

to resurrect the Column, On his own previous proposition, Gustave

Courbet was singled out and condemned to pay the expenses. Unable to

pay, Courbet went into a self-imposed exile in Switzerland. He took

refuge in Switzerland to avoid bankruptcy. The next years he

participated quite actively in some regional and national exhibitions.

Observed by the intelligence service he enjoyed in the small Swiss art

world the dubious reputation as head of the “realist school” and

inspired younger artists like Auguste Baud-Bovy and Ferdinand Hodler. From this period date several paintings of trout, "hooked and bleeding from the gills", that have been interpreted as allegorical self-portraits of the exiled artist. On

4 May 1877, the estimate of the costs was finally established: 323,091

fr 68 cent. Courbet was allowed to pay the fine in yearly installments

of 10,000 francs for the next 33 years, until his 91st birthday. On 31

December 1877, a day before the payment of the first installment was

due, Courbet died, age 58, in La Tour-de-Peilz, Switzerland, of a liver disease aggravated by heavy drinking.