<Back to Index>

- Engineer David Bernard Steinman, 1886

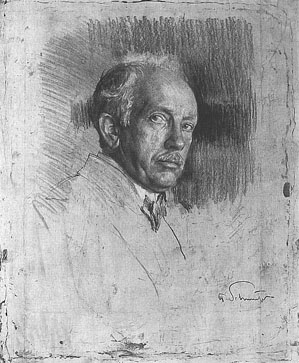

- Composer Richard Georg Strauss, 1864

- Member of Congress Jeannette Pickering Rankin, 1880

Richard Georg Strauss (11 June 1864 – 8 September 1949) was a German composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras, particularly of operas, Lieder and tone poems. Strauss was also a prominent conductor.

Strauss was born on 11 June 1864, in Munich, the son of Franz Strauss, who was the principal horn player at the Court Opera in Munich. In his youth, he received a thorough musical education from his father. He wrote his first music at the age of six, and continued to write music almost until his death. During his boyhood Strauss attended orchestra rehearsals of the Munich Court Orchestra, and he also received private instruction in music theory and orchestration from an assistant conductor there. In 1874 Strauss heard his first Wagner operas, Lohengrin and Tannhäuser. The influence of Wagner's music on Strauss's style was to be profound, but at first his musically conservative father forbade him to study it: it was not until the age of 16 that he was able to obtain a score of Tristan und Isolde. Indeed, in the Strauss household the music of Richard Wagner was considered inferior. Later in life, Richard Strauss said and wrote that he deeply regretted this.

In 1882 he entered Munich University, where he studied philosophy and art history, but not music. He left a year later to go to Berlin, where he studied briefly before securing a post as assistant conductor to Hans von Bülow, taking over from him at Meiningen when von Bülow resigned in 1885. His compositions at this time were indebted to the style of Robert Schumann or Felix Mendelssohn, true to his father's teachings. His Horn Concerto No. 1 (1882–1883) is representative of this period and is still regularly played.

Richard Strauss married soprano Pauline de Ahna on

10 September 1894. She was famous for being bossy, ill-tempered,

eccentric and outspoken, but the marriage, to all appearances, was

essentially happy and she was a great source of inspiration to him.

Throughout his life, from his earliest songs to the final Four Last Songs of 1948, he preferred the soprano voice to all others. Nearly every major operatic role that Strauss wrote is for a soprano. Strauss's style began to change when he met Alexander Ritter, a noted composer and violinist, and the husband of one of Richard Wagner's

nieces. It was Ritter who persuaded Strauss to abandon the conservative

style of his youth, and begin writing tone poems; he also introduced

Strauss to the essays of Richard Wagner and the writings of Arthur Schopenhauer. Strauss went on to conduct one of Ritter's operas, and later Ritter wrote a poem based on Strauss's own Death and Transfiguration (Tod und Verklärung). This newly found interest resulted in what is widely regarded as Strauss's first piece to show his mature personality, the tone poem Don Juan. Strauss went on to write a series of other tone poems, including Death and Transfiguration, 1888–1889), Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks (Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche, 1894–95), Thus Spoke Zarathustra (Also sprach Zarathustra, 1896), Don Quixote (1897), Ein Heldenleben (A Hero's Life, 1897–98), Sinfonia Domestica (Domestic Symphony, 1902–03) and An Alpine Symphony (Eine Alpensinfonie), (1911–1915). Around the end of the 19th century, Strauss turned his attention to opera. His first two attempts in the genre, Guntram in 1894 and Feuersnot in 1901 were considered obscene and were critical failures. However, in 1905 he produced Salome (based on the play by Oscar Wilde),

and the reaction was passionate and extreme. The première was a

major success, with the artists taking more than thirty-eight curtain

calls. When it opened at the Metropolitan Opera in

New York City, there was such a public outcry that it was closed after

just one performance. Doubtless, much of this was due to the subject

matter, and negative publicity about Wilde's "immoral" behavior.

However, some of the negative reactions may have stemmed from Strauss's

use of dissonance, rarely heard then at the opera house. Elsewhere the

opera was highly successful and Strauss reputedly financed his house in Garmisch-Partenkirchen completely from the revenues generated by the opera. Strauss's next opera was Elektra, which took his use of dissonance even further. It was also the first opera in which Strauss collaborated with the poet Hugo von Hofmannsthal.

The two would work together on numerous other occasions. For these

later works, however, Strauss moderated his harmonic language somewhat, with the result that works such as Der Rosenkavalier (1910) were great public successes. Strauss continued to produce operas at regular intervals until 1940. These included Ariadne auf Naxos (1912), Die Frau ohne Schatten (1918), Die ägyptische Helena (1927), and Arabella (1932), all in collaboration with Hofmannsthal; and Intermezzo (1923), for which Strauss provided his own libretto, Die schweigsame Frau (1934), with Stefan Zweig as librettist; Friedenstag (1936) and Daphne (1937) (libretto by Joseph Gregor and Zweig); Die Liebe der Danae (1940) (with Gregor) and Capriccio (libretto by Clemens Krauss) (1941). Strauss also made live-recording player piano music rolls for the Hupfeld system, all of which survive today. Strauss's

solo and chamber works include early compositions for piano solo in a

conservative harmonic style, many of which are lost; a rarely heard

string quartet (opus 2); the famous violin sonata in E flat which he

wrote in 1887; as well as a handful of late pieces. There are only six

works in his entire output dating from after 1900 which are for chamber

ensembles, and four are arrangements of portions of his operas. His

last chamber work, an Allegretto in E for violin and piano, dates from 1940. Much

more extensive was his output of works for solo instrument or

instruments with orchestra. The most famous include two horn concerti,

which are still part of the standard repertoire of most horn soloists; a concerto for violin; Burleske for piano and orchestra; the tone poem Don Quixote, for cello, viola and orchestra; a late oboe concerto (inspired by a request from an American soldier and oboist, John de Lancie,

whom he met after the war); and the Duet-Concertino for bassoon,

clarinet and orchestra, which was one of his last works (1947). Strauss

admitted that the Duet-Concertino had an extra-musical "plot", in which

the clarinet represented a princess and the bassoon a bear; when the

two dance together, the bear transforms into a prince. There is much controversy surrounding Strauss's role in Germany after the Nazi Party came to power. Some say that he was constantly apolitical, and never cooperated with the Nazis completely. Others point out that he was an official of the Third Reich. Several noted musicians disapproved of his conduct while the Nazis were in power, among them the conductor Arturo Toscanini, who famously said, "To Strauss the composer I take off my hat; to Strauss the man I put it back on again." In November 1933 Joseph Goebbels appointed him to the post of president of the Reichsmusikkammer,

the State Music Bureau. Strauss decided to keep his post but to remain

apolitical, a decision which has been criticized as naïve. While in this position he composed the Olympische Hymne for the 1936 Summer Olympics,

and also befriended some high-ranking Nazis. Evidently his intent was

to protect his daughter-in-law Alice, who was Jewish, from persecution. In 1935, Strauss was forced to resign his position as Reichsmusikkammer president, after refusing to remove from the playbill for Die schweigsame Frau the name of the Jewish librettist, his friend Stefan Zweig. He had written Zweig a supportive letter, insulting to the Nazis, which was intercepted by the Gestapo. By the time he conducted the Olympische Hymne at the Berlin Olympic Stadium in 1936, he was no longer president of the Reichsmusikkammer. His decision to produce Friedenstag in 1938, a one-act opera set in a besieged fortress during the Thirty Years' War –

essentially a hymn to peace and a thinly veiled criticism of the Third

Reich – during a time when an entire nation was preparing for war, has

been seen as extraordinarily brave. With

its contrasts between freedom and enslavement, war and peace, light and

dark, this work has been considered by some to be more related to Fidelio than to any of Strauss's other operas. Production ceased shortly after the outbreak of war in 1939. When his daughter-in-law Alice was placed under house arrest in Garmisch-Partenkirchen in 1938, Strauss used his connections in Berlin, for example the Berlin intendant Heinz Tietjen,

to secure her safety; in addition, there are also suggestions that he

attempted to use his official position to protect other Jewish friends

and colleagues. Unfortunately, Strauss left no specific records or commentary regarding his feeling about Nazi antisemitism,

so most of the reconstruction of his motivations during the period is

conjectural. While most of his actions during the 1930s were midway

between collaboration and dissidence, it was only in his music that the

dissident streak was, in retrospect, more obvious (such as in the

pacifist drama Friedenstag.). In 1942, Strauss moved with his family back to Vienna, where Alice and her children could be protected by Baldur von Schirach, the Gauleiter of

Vienna. Unfortunately, even Strauss was unable to protect his Jewish

relatives completely; in early 1944, while Strauss was away, Alice and

the composer's son were abducted by the Gestapo and imprisoned for two

nights. Only Strauss's personal intervention at this point was able to

save them and he was able to take the two of them back to Garmisch

where they remained under house arrest until the end of the war. Strauss completed the composition of Metamorphosen, a work for 23 solo strings, in 1945. It is now generally accepted that Metamorphosen was composed, specifically, to mourn the bombing of Strauss's favorite opera house, the Hoftheater in

Munich. Strauss called this "the greatest catastrophe that has ever

disturbed my life." However, some scholars suggest that the original

intention of the piece was to be a choral setting of Goethe's poem, Niemand wird sich selber kennen. In

April 1945, Strauss was apprehended by American soldiers at his

Garmisch estate. As he descended the staircase he announced to

Lieutenant Milton Weiss of the US Army, "I am Richard Strauss, the

composer of Rosenkavalier and Salome."

Lt. Weiss, who, as it happened, was also a musician, nodded in

recognition. Another musically knowledgeable American officer placed an

'Off limits' sign on the lawn to protect Strauss. The English playwright Ronald Harwood wrote Collaboration (2008), a play largely sympathetic of Strauss. Themes in this play interweave with Harwood's more ambiguous treatment of Wilhelm Furtwängler in Taking Sides (1995), and many of the characters and events are mentioned or figure in both plays. In 1948, Strauss wrote his last work, Four Last Songs for soprano and orchestra, reportedly with Kirsten Flagstad in

mind. She certainly gave the first performance and it was recorded, but

the quality of the recording is poor. It is available as a historic CD

release for enthusiasts. All his life he had produced lieder, but these are among his best known (alongside "Zueignung", "Cäcilie", "Morgen!" and "Allerseelen").

Compared to the work of younger composers, Strauss's harmonic and

melodic language was somewhat old-fashioned by this time. Nevertheless,

the songs and tone poems have always been popular with audiences and

performers. Strauss himself declared in 1947, "I may not be a

first-rate composer, but I am a first-class second-rate composer!" Richard Strauss died at the age of 85 on 8 September 1949, in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany. Georg Solti, who had arranged Strauss's 85th birthday celebration, also directed an orchestra during Strauss's burial.