<Back to Index>

- Chemist Lloyd Augustus Hall, 1894

- Sculptor Jacques François Joseph Saly, 1717

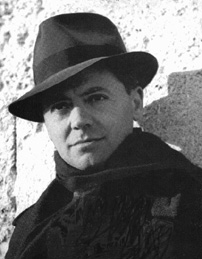

- Member of the French Resistance Jean Moulin, 1899

Jean Moulin (June 20, 1899 – July 8, 1943) was a high-profile member of the French Resistance during World War II. He is remembered today as an emblem of the Resistance primarily due to his courage and death at the hands of the Germans.

Moulin was born in Béziers, France, and enlisted in the French Army in 1918. After World War I, he resumed his studies and obtained a degree in law in 1924. He then entered the prefectural administration as chef de cabinet to the deputy of Savoie in 1922, then as sous préfet of Albertville, from 1925 to 1930. He was France's youngest sous préfet at the time.

He married Marguerite Cerruti in September 1926, but the couple divorced in 1928.

In 1930, he was the sous préfet of Châteaulin. During that time, he also drew political cartoons in the newspaper Le Rire under the pseudonym Romanin. He also became an illustrator for the poet Tristan Corbière's books, among others he made an etching for La Pastorale de Conlie, a book about the camp of Conlie where many Breton soldiers died in 1870. He also made friends with the Breton poets Saint-Pol-Roux in Camaret and Max Jacob in Quimper. He became France's youngest préfet in the Aveyron département, in the commune of Rodez, in January 1937.

During the Spanish Civil War, some believe he supplied arms from the Soviet Union to Spain.

A more commonly accepted version of events is that he supplied French

planes to the anti-fascist forces from his position within the Aviation

Ministry. In 1939, Moulin was appointed préfet of the Eure-et-Loir département. The Germans arrested him in June 1940 because he refused to sign a German document that falsely blamed Senegalese French Army troops for civilian massacres. In prison, he attempted suicide by

cutting his throat with a piece of broken glass. This left him with a

scar that he would often hide with a scarf — the image of Jean Moulin

remembered today. In November 1940, the Vichy government ordered all préfets to dismiss left-wing elected mayors of towns and villages. When Moulin refused, he was himself removed from office. He then lived in Saint-Andiol (Bouches-du-Rhône), and joined the French Resistance. Moulin reached London in September 1941 under the name Joseph Jean Mercier, and met General Charles de Gaulle, who asked him to unify the various resistance groups. On January 1, 1942, he parachuted into the Alpilles. Under the code names Rex and Max, he met with the leaders of the resistance groups: In his work in the Resistance, he was aided by his private administrative assistant Laure Diebold. In February 1943, Moulin went back to London, accompanied by Charles Delestraint, head of the new Armée secrète group. He left on March 21, 1943 with orders to form the Conseil national de la Résistance (CNR),

a difficult task since each resistance movement wanted to keep its

independence. The first meeting of the CNR took place in Paris on May 27, 1943. On June 21, 1943, Jean Moulin met with most of the Resistance leaders in the home of Doctor Frédéric Dugoujon in Caluire-et-Cuire, a suburb of Lyon. Moulin, Dugoujon, Henri Aubry (alias Avricourt and Thomas), Raymond Aubrac, Bruno Larat (alias Xavier-Laurent Parisot), André Lassagne (alias Lombard), Colonel Albert Lacaze, Colonel Emile Schwarzfeld (alias Blumstein) and René Hardy (alias Didot) were arrested. Interrogated in Lyon by Klaus Barbie, head of the Gestapo there, and later in Paris, Moulin never revealed anything to his captors. He eventually died near Metz,

probably due to injuries suffered either during the torture itself or

in a suicide attempt, as Barbie alleged. Moulin's biographer, Patrick

Marnham, supports the latter explanation, though it is widely believed

that Barbie personally beat Moulin to death. René Hardy was caught and released by the Gestapo. They followed him when he came to the meeting at the doctor's house. Some believe that this was a deliberate act of treason; others think René Hardy was simply reckless. Two trials concluded that he was innocent. A

recent TV film about the life and death of Jean Moulin depicted

René Hardy collaborating with the Gestapo, thus reviving the

controversy. The Hardy family attempted to bring a lawsuit against the

producers of the movie. There

have been many allegations in the post-war years that Moulin was a

Communist because some of his friends were. No hard evidence has ever

backed up this claim. Marnham looked into the allegations, but found no

evidence to support the accusation (though members of the party could

easily have seen him as a 'fellow traveler' due to his Communist

friends and support for the anti-fascist forces in Spain). As

préfet, Moulin even ordered the repression of Communist

'agitators' and went so far as to have police keep some under

surveillance. It

has also been suggested, principally in Marnham's biography, that

Moulin was betrayed by Communists. Marnham specifically points the

finger at Raymond Aubrac and possibly at his wife, Lucie Aubrac.

He makes the case that Communists did at times betray non-Communists to

the Gestapo and that Aubrac has been linked to harsh actions during the

purge of collaborators after the war. To

counteract the accusations leveled at Moulin, his personal secretary

during the war, Daniel Cordier, has written his own biography of his

former leader. Moulin was initially buried in Le Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. His ashes were later transferred to The Panthéon on December 19, 1964. The speech given by André Malraux, writer and minister of the Republic, upon the transfer of his ashes is one of the most famous speeches in French history. Today,

Jean Moulin is used in French education to illustrate civic virtues,

moral rectitude and patriotism. He is a symbol of the Resistance. Many

schools and a university (Lyon III), as well as innumerable streets,

squares and even a Paris tram station have been named after him. The Musée Jean Moulin commemorates his life and the Resistance. Jean Moulin is the third most popular name for a French Ecole primaire, Collège, and Lycée. Jean

Moulin became the most famous and honoured French Resistance fighter.

He is known by practically all French people, thanks to his famous

monochrome photo, with his hack and his fedora. Other martyrs of the

clandestine fight, such as Pierre Brossolette, Jean Cavaillès or Jacques Bingen, all of them organizers of the underground army, are overshadowed by his legend.