<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Wilhelm von Humboldt, 1767

- Architect Nicolai Eigtved, 1701

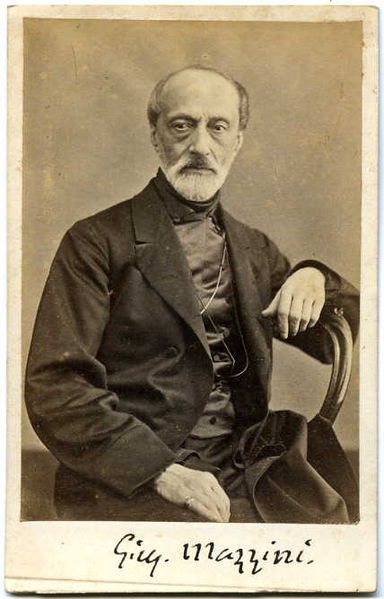

- Member of Triumvirate of the Roman Republic Giuseppe Mazzini, 1805

Giuseppe Mazzini (June 22, 1805 – March 10, 1872), the "Soul of Italy," was an Italian patriot, philosopher and politician. His efforts helped bring about the modern Italian state in place of the several separate states, many dominated by foreign powers, that existed until the 19th century. He also helped define the modern European movement for popular democracy in a republican state.

Mazzini was born in Genoa, then part of the Ligurian Republic, under the rule of the French Empire. His father, Giacomo, was a university professor who had adhered to Jacobin ideology; his mother, Maria Drago, was renowned for her beauty and religious fervour. Since a very early age, Mazzini showed good learning qualities (as well as a precocious interest towards politics and literature), and was admitted to the University at only 14, graduating in law in 1826, initially practicing as a "poor man's lawyer". He also hoped to become a historical novelist or a dramatist, and in the same year he wrote his first essay, Dell'amor patrio di Dante ("On Dante's Patriotic Love"), which was published in 1837. In 1828–29 he collaborated with a Genoese newspaper, L'indicatore genovese, which was however soon closed by the Piedmontese authorities.

In 1830 Mazzini traveled to Tuscany, where he became a member of the Carbonari, a secret association with political purposes. On October 31st of that year he was arrested at Genoa and interned at Savona.

During his imprisonment he devised the outlines of a new patriotic

movement aiming to replace the unsuccessful Carbonari. Although freed

in the early 1831, he chose exile instead of life confined into the

small hamlet which was requested of him by the police, moving to Geneva in Switzerland. In 1831 he went to Marseille, where he became a popular figure to the other Italian exiles. He lived in the apartment of Giuditta Bellerio Sidoli, a beautiful Modenese widow who would become his lover, and organized a new political society called La giovine Italia (Young

Italy). Young Italy was a secret society formed to promote Italian

unity. Mazzini believed that a popular uprising would create a unified

Italy, and would touch off a European-wide revolutionary movement. The group's motto was God and the People, and

its basic principle was the union of the several states and kingdoms of

the peninsula into a single republic as the only true foundation of

Italian liberty. The new nation had to be: "One, Independent, Free

Republic". The Mazzinian propaganda met some success in Tuscany, Abruzzi, Sicily, Piedmont and his native Liguria, especially among several military officers. Young Italy counted ca 60,000 adherents in 1833, with branches in Genoa and other cities. In that year Mazzini launched a first attempt of insurrection, which would spread from Chambéry (then part of the Kingdom of Sardinia), Alessandria, Turin and Genoa. However, the Savoy government discovered the plot before it could begin and many revolutionaries (including Vincenzo Gioberti)

were arrested. The repression was ruthless: 12 participants were

executed, while Mazzini's best friend and director of the Genoese

section of the Giovine Italia, Jacopo Ruffini, killed himself. Mazzini was tried in absence and sentenced to death. Despite

this setback (whose victims later created numerous doubts and

psychological strife in Mazzini), he organized another uprising for the

following year. A group of Italian exiles were to enter Piedmont from

Switzerland and spread the revolution there, while Giuseppe Garibaldi, who had recently joined the Giovine Italia, was to do the same from Genoa. However, the Piedmontese troops easily crushed the new attempt. On May 28, 1834 Mazzini was arrested at Solothurn,

and exiled from Switzerland. He moved to Paris, where he was again

imprisoned on July 5. He was released only after promising he would

move to England. Mazzini, together with a few Italian friends, moved in

January 1837 to live in London in very poor economic conditions. On April 30, 1837 Mazzini reformed the Giovine Italia in London, and on November 10 of the same year he began issuing the Apostolato popolare ("Apostleship of the People"). A succession of failed attempts at promoting further uprising in Sicily, Abruzzi, Tuscany and Lombardy-Venetia discouraged

Mazzini for a long period, which dragged on until 1840. He was also

abandoned by Sidoli, who had returned to Italy to rejoin her children.

The help of his mother pushed Mazzini to found several organizations

aimed at the unification or liberation of other nations, in the wake of Giovine Italia: Young Germany, Young Poland, Young Switzerland, which were under the aegis of Young Europe (Giovine Europa).

He also created an Italian school for poor people. From London he also

wrote an endless series of letters to his agents in Europe and South

America, and made friends with Thomas and Jane Welsh Carlyle.

The "Young Europe" movement also inspired a group of young Turkish army

cadets and students who, later in history, named themselves the "Young Turks". In 1843 he organized another riot in Bologna, which attracted the attention of two young officers of the Austrian Navy, Attilio and Emilio Bandiera. With Mazzini's support, they landed near Cosenza (Kingdom of Naples),

but were arrested and executed. Mazzini accused the British government

of having passed information about the expeditions to the Neapolitans,

and question was raised in the British Parliament. When it was admitted

that his private letters had indeed been opened, and its contents

revealed by the Foreign Office to the Neapolitan government, Mazzini

gained popularity and support among the British liberals, who were

outraged by such a blatant intrusion of the government into his private

correspondence. In 1847 he moved again to London, where he wrote a long "open letter" to Pope Pius IX,

whose apparently liberal reforms had gained him a momentary status as

possible paladin of the unification of Italy. The Pope, however, did

not reply. He also founded the People's International League. By March 8, 1848 Mazzini was in Paris, where he launched a new political association, the Associazione Nazionale Italiana. On April 7, 1848 Mazzini reached Milan, whose population had rebelled against the Austrian garrison and established a provisional government. The First Italian War of Independence, started by the Piedmontese king Charles Albert to

exploit the favourable circumstances in Milan, turned into a total

failure. Mazzini, who had never been popular in the city because he

wanted Lombardy to become a republic instead of joining Piedmont,

abandoned Milan. He joined Garibaldi's irregular force at Bergamo, moving to Switzerland with him. On February 9, 1849 a Republic was declared in Rome, with Pius IX forced to flee to Gaeta.

On February 9 of that year Mazzini reached the city, and was appointed

as "triumvir" of the new republic on March 29, becoming soon the true

leader of the government and showing good administrative capabilities

in social reforms. However, when the French troops called by the Pope

made clear that the resistance of the Republican troops, led by

Garibaldi, was in vain, on July 12, 1849 Mazzini set out for Marseille,

from where he moved again to Switzerland. Mazzini spent all of 1850

hiding from the Swiss police. In July he founded the association Amici di Italia (Friends of Italy) in London, to attract consensus towards the Italian liberation cause. Two failed riots in Mantua (1852) and Milan (1853)

were a crippling blow for the Mazzinian organization, whose prestige

never recovered. He later opposed the alliance signed by Savoy with

Austria for the Crimean War. Also vain was the expeditions of Felice Orsini in Carrara of 1853–54. In 1856 he returned to Genoa to organize a series of uprisings: the only serious attempt was that of Carlo Pisacane in Calabria,

which again met a dismaying end. Mazzini managed to escape the police,

but was condemned to death by default. From this moment on, Mazzini was

more of a spectator than a protagonist of the Italian Risorgimento,

whose reins were now strongly in the hands of the Savoyard monarch Victor Emmanuel II and his skilled prime minister, Camillo Benso, Conte di Cavour. The latter defined him as "Chief of the assassins". In 1858 he founded another journal in London, Pensiero e azione ("Thought

and Action"). Also there, on February 21, 1859, together with 151

republicans he signed a manifesto against the alliance between Piedmont

and the King of France which resulted in the Second War of Italian Independence and the conquest of Lombardy. On May 2, 1860 he tried to reach Garibaldi, who was going to launch his famous Expedition of the Thousand in southern Italy. In the same year he released Doveri dell'uomo ("Duties

of Man"), a synthesis of his moral, political and social thoughts. In

mid-September he was in Naples, then under Garibaldi's dictatorship,

but was invited by the local vice-dictator Giorgio Pallavicino to move away. In 1862 he again joined Garibaldi during his failed attempt to free Rome. In 1866 Venetia was ceded by France, who had obtained it from Austria at the end of the Austro-Prussian War, to the new Kingdom of Italy,

which had been created in 1861 under the Savoy monarchy. At this time

Mazzini was frequently in polemics with the course followed by the

unification of his country, and in 1867 he refused a seat in the

Italian Chamber of Deputies. In 1870, during an attempt to free Sicily,

he was arrested and imprisoned in Gaeta. He was freed in October due to

the amnesty conceded after the successful capture of Rome, and returned to London in mid-December. Giuseppe Mazzini died in Pisa in 1872. His funeral was held in Genoa, with 100,000 people taking part in it. Karl Marx, on an interview by R. Landor in 1871, said that Mazzini's ideas

represent "nothing better than the old idea of a middle-class

republic." Marx believed, especially after the Revolutions of 1848, that this alleged middle class point of view had become reactionary and the proletariat had nothing to do with it. Mazzini was an early advocate of a "United States of Europe" about a century before the European Union began to take shape. For him, European unification was a logical continuation of Italian unification.