<Back to Index>

- Engineer George Washington Goethals, 1858

- Sculptor Hiram Powers, 1805

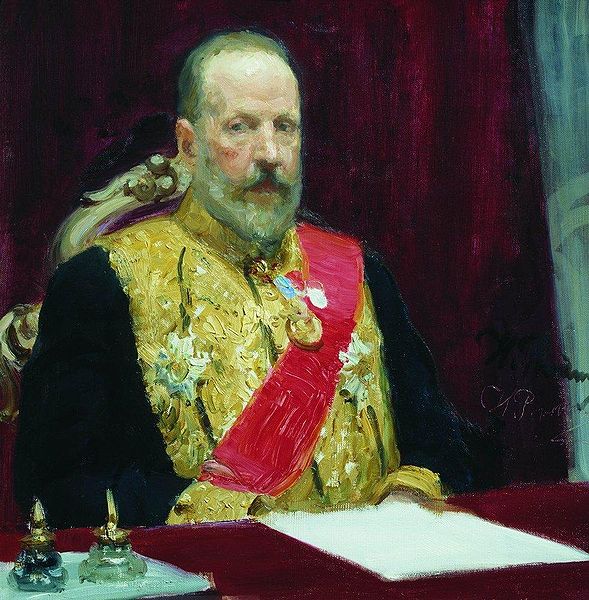

- 1st Prime Minister of Imperial Russia Count Sergei Yulyevich Witte, 1849

Count Sergei Yulyevich Witte (Russian: Сергей Юльевич Витте) (29 June 1849 - 13 March 1915), also known as Sergius Witte, was a highly influential policy-maker who presided over extensive industrialization within the Russian Empire. He served under the last two emperors of Russia. He was also the author of the October Manifesto of 1905, a precursor to Russia's first constitution, and Chairman of the Council of Ministers (Prime Minister) of the Russian Empire.

Witte's father Julius Witte came from a Lutheran Baltic German (originally Dutch) family and had been member of the knightage of the City of Pskov. He converted to Orthodoxy upon marriage with Witte's mother Catherine Fadeyev. Sergei Witte's maternal grandfather was Andrei Mikhailovich Fadeyev, a Governor of Saratov and Privy Councillor of the Caucasus, his grandmother was Princess Helene Dolgoruki, and the mystic Madame Blavatsky was his first cousin. He was born in Tiflis, Georgia and raised in the house of his mother's parents. He finished Gymnasium I in Chisinau and graduated from Novorossiysk University in Odessa with a degree in mathematics.

After

graduating he then spent the greater part of the 1870s and 1880s

involved in private enterprises, particularly the administration and

management of various railroad lines in Russia. Witte served as Russian Director

of Railway Affairs within the Finance Ministry from 1889 - 1891; and

during this period, he oversaw an ambitious program of railway

construction which included the building of the Trans-Siberian Railway. The Tsar appointed him acting Minister of Ways and Communications in 1892. Nicholas II transferred Witte to the position of chairman of the Committee of Ministers in 1905, a position he held until 1906. In

an attempt to keep up the modernization of the Russian economy Witte

called and oversaw the Special Conference on the Needs of the Rural

Industry. This conference was to provide recommendations for future

reforms and the data to justify those reforms. Witte's

opposition to Russian designs on Korea caused him to resign from

government in 1903. He returned to the forefront in 1905, however, when

he was called upon by the Tsar to negotiate an end to the Russo-Japanese War. He

was sent as the Russian Emperor's plenipotentiary and titled "his

Secretary of State and President of the Committee of Ministers of the

Emperor of Russia" along with Baron Roman Rosen, Master of the Imperial Court of Russia to the United States, where the peace talks were being held. Witte

is credited with negotiating brilliantly on Russia's behalf. Despite

losing dramatically on the battlefield, Russia lost very little in the

final settlement. For his efforts, Witte was created a Count. But the loss of the war would perhaps spell the beginning of the end of Imperial Russia. After

this diplomatic success, Witte was brought back into the governmental

decision-making process to help deal with the civil unrest following

the war and Bloody Sunday. He was appointed Chairman of the Council of Ministers, the equivalent of Prime Minister, in 1905. During the Russian Revolution of 1905, Witte advocated the creation of an elected parliament, the formation of a constitutional monarchy, and the establishment of a Bill of Rights through the October Manifesto.

Many of his reforms were put into place, but they failed to end the

unrest. This, and overwhelming victories by left-wing political parties

in Russia's first elected parliament, the State Duma, forced Witte to resign as Chairman of the Council of Ministers. Witte

continued in Russian politics as a member of the State Council but

never again obtained an administrative role in the government. Just

prior to the outbreak of World War I,

he urged that Russia stay out of the conflict. His warning that Europe

faced calamity if Russia became involved went unheeded, and he died

shortly afterwards. Witte's

reputation was burnished in the West when his memoirs were published in

1921. The original text of these memoirs are held in Columbia

University Library's Bakhmeteff Archive of Russian and East European

History and Culture.