<Back to Index>

- Optician Joseph von Fraunhofer, 1787

- Painter, Sculptor, Architect, Poet and Engineer Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, 1475

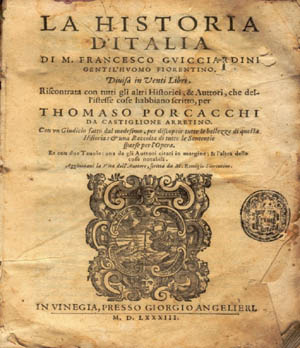

- Historian and Statesman Francesco Guicciardini, 1483

Francesco Guicciardini (March 6, 1483 - May 22, 1540) was an Italian historian and statesman. A friend and critic of Niccolò Machiavelli, he is considered one of the major political writers of the Italian Renaissance. Guicciardini is considered as the Father of Modern History, due to his use of government documents to verify his "History of Italy."

Guicciardini was born in Florence in the year 1483, when Marsilio Ficino held

him at the font of baptism. His family was illustrious and noble; and

his ancestors for many generations had held the highest posts of honor

in the state, as may be seen in his own genealogical Ricordi autobiografici e di famiglia.

After the usual education of a boy in grammar and elementary classical

studies, his father, Piero, sent him to the universities of Ferrara and Padua, where he stayed until the year 1505. The death of an uncle, who had occupied the see of Cortona with

great pomp, induced the young Guicciardini to hanker after an

ecclesiastical career. Guicciardini, whose motives were confessedly

ambitious, then turned his attention to law, and at the age of

twenty-three was appointed by the Signoria of Florence to read the Institutes in public. Shortly afterwards he engaged himself in marriage to Maria, daughter of Alamanno Salviati,

prompted, as he frankly tells us, by the political support which an

alliance with that great family would bring him. He was then practicing

at the bar, where he won so much distinction that the Signoria, in

1512, entrusted him with an embassy to the court of the King of Aragon, Ferdinand the Catholic. Thus

he entered on the real work of his life as a diplomat and statesman.

His conduct upon that legation was afterwards severely criticized; for

his political antagonists accused him of betraying the true interests

of the commonwealth, and using his influence for the restoration of the

exiled house of Medici to power. His Spanish correspondence

with the Signoria reveals the extraordinary power of observation and

analysis which was a chief quality of his mind. In 1513 Giovanni Medici, the son of Lorenzo the Magnificent, became Pope Leo X and

brought Florence under Papal control. This provided opportunities for

Florentines to enter Papal service, and in 1515 he began working for

the papacy. Leo X made him governor of Reggio in 1516 and Modena in 1517. This was the beginning of a long career for Guicciardini in Papal administration, first under Leo X, and then his successor, Clement VII. "He governed Modena and Reggio with conspicuous success," according to The Catholic Encyclopedia, and he was appointed to govern Parma. In that city, according to the Encyclopedia, "in the confusion that followed the pope's death, he distinguished himself by his defence of Parma against the French (1521)." In 1523 he was appointed viceregent of Romagna by Pope Clement VII ( 1478 – 1534). These high offices rendered Guicciardini the virtual master of the papal states beyond the Apennines,

during a period of great bewilderment and difficulty. The copious

correspondence relating to his administration has recently been

published. In 1526 Clement gave him still higher rank as lieutenant-general of the papal army. While holding this commission, he had the humiliation of witnessing from a distance the sack of Rome and the imprisonment of Clement, without being able to rouse the perfidious Duke of Urbino into

activity. The blame of Clement's downfall did not rest with him; for it

was merely his duty to attend the camp, and keep his master informed of

the proceedings of the generals. Guicciardini went to Florence, but by

1527 the Medici had been expelled from the city and a republic set up.

Because of his close ties to the Medici, Guicciardini was held suspect

in his native city, and he fled in 1529 to the Papal Court. In 1531 Guicciardini was advanced to the governorship of Bologna, the most important of all the papal lord-lieutenancies. This post he resigned in 1534 on the election of Paul III,

preferring to follow the fortunes of the Medici princes. It may here be

noticed that though Guicciardini served three popes through a period of

twenty years, or perhaps because of this, he hated the papacy with a

deep and frozen bitterness, attributing the woes of Italy to the

ambition of the church, and declaring he had seen enough of sacerdotal

abominations to make him a Lutheran.

The same discord between his private opinions and his public actions

may be traced in his conduct subsequent to 1534. As a political

theorist, Guicciardini believed that the best form of government was a

commonwealth administered upon the type of the Venetian constitution;

and we have ample evidence to prove that he had judged the tyranny of

the Medici at its true worth. Yet he did not hesitate to place his

powers at the disposal of the most vicious members of that house for

the enslavement of Florence. In 1527 he had been declared a rebel by

the Signoria on account of his well-known Medicean prejudices; and in

1530, deputed by Clement to punish the citizens after their revolt, he

revenged himself with a cruelty and an avarice that were long and

bitterly remembered. When, therefore, he returned to inhabit Florence in 1534, he did so as the creature of the dissolute Alessandro de Medici. Guicciardini pushed his servility so far as to defend this infamous despot at Naples in 1535, before the bar of Charles V,

from the accusations brought against him by the Florentine exiles. He

won his case; but in the eyes of all posterity he justified the

reproaches of his contemporaries, who describe him as a cruel, venal,

grasping seeker after power, eager to support a despotism for the sake

of honors, offices and emoluments secured for himself by a bargain with

the oppressors of his country. After the murder of Duke Alessandro in 1537, Guicciardini espoused the cause of Cosimo de Medici,

a boy addicted to field sports, and unused to the game of statecraft.

The wily old diplomatist hoped to rule Florence as grand vizier under

this inexperienced princeling. He was mistaken, however, in his

schemes, for Cosimo displayed the genius of his family for politics,

and coldly dismissed his would-be lord-protector. Guicciardini retired

in disgrace to his villa (at Arcetri), where he spent his last years in the composition of the Storia d'Italia. He died in 1540 without male heirs. His nephew, Lodovico Guicciardini, was also an historian particularly well-known for his 16th-century works on the Low Countries.