<Back to Index>

- Chemist Otto Hahn, 1879

- Poet João de Deus Ramos, 1830

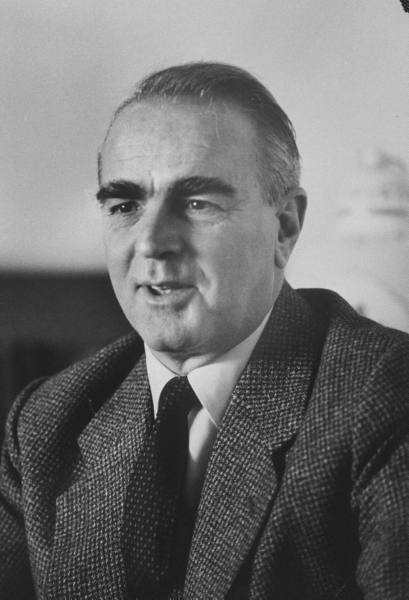

- President of the Hellenic Republic Konstantinos Karamanlis, 1907

Konstantinos or Constantine Karamanlis (Greek: Κωνσταντίνος Καραμανλής) (8 March 1907 - 23 April 1998) was a Prime Minister, President of Greece and a towering figure of Greek politics whose political career spanned much of the latter half of the 20th century.

He was born in the town of Proti, Macedonia, Ottoman Empire (now Greece). He became a Greek citizen in 1913, after Macedonia was united with Greece in the aftermath of the Second Balkan War. His father was Georgios Karamanlis, a teacher who fought during the Greek Struggle for Macedonia, in 1904–1908. After spending his childhood in Macedonia, he went to Athens to attain his degree in Law. He practised law in Serres, entered politics with the conservative People's Party and was elected Member of Parliament for the first time at the age of 28, in the Greek legislative election, 1936. Due to health problems, Karamanlis did not participate in the Greco-Italian War.

After World War II,

Karamanlis quickly rose through the ranks of Greek politics. His rise

was strongly supported by fellow party-member and close friend Lambros Eftaxias who served as Minister for Agriculture under the premiership of Konstantinos Tsaldaris. Karamanlis's first cabinet position was Minister for Employment in 1947 under the same administration. Karamanlis eventually became Minister of Public Works in the Greek Rally administration under Prime Minister Alexandros Papagos.

He won the admiration of the US Embassy for the efficiency with which

he built road infrastructure and administered American aid programs. When Alexandros Papagos died after a brief illness (1955), King Paul of Greece appointed the 48-year-old Karamanlis as Prime Minister. The King did so, thus bypassing Stephanos Stephanopoulos and Panagiotis Kanellopoulos,

the two senior Greek Rally politicians who were widely considered as

the heavyweights most likely to succeed Papagos. Karamanlis first

became prime minister in 1955, and reorganized the Greek Rally as the National Radical Union.

One of the first bills he promoted as Prime Minister, implemented the

extension of full voting rights to women, which stood dormant although

nominally approved in 1952. Karamanlis won three successive elections (1956,1958 and 1961). In

1959 he announced a five-year plan (1960–64) for the Greek economy,

emphasizing improvement of agricultural and industrial production,

heavy investment on infrastructure and the promotion of tourism. On the

international front, Karamanlis abandoned the government's previous

strategic goal for enosis (the unification of Greece and Cyprus) in favour of independence for Cyprus. In 1958, his government engaged in negotiations with the United Kingdom and Turkey, which culminated in the Zurich Agreement as a basis for a deal on the independence of Cyprus. In 1959 the plan was ratified in London by Makarios III. Max Merten was Kriegverwaltungsrat (military administration counselor) of the Nazi German occupation forces in Thessaloniki. He was convicted in Greece and sentenced to a 25 year term as a war criminal in 1959. On 3 November of that year, Merten benefited from an amnesty for war criminals, and was set free and extradited to the Federal Republic of Germany, after political and economic pressure from West Germany (which, at the time, hosted thousands of Greek economic immigrants). Merten's arrest also enraged Queen Frederica, a woman with German ties, who wondered whether "this is the way mister district attorney understands the development of German and Greek relations". In Germany, Merten was eventually acquitted from all charges due to "lack of evidence." On 28 September 1960 German newspapers Hamburger Echo and Der Spiegel published excerpts of Merten's deposition to the German authorities where Merten claimed that Karamanlis, the then Minister for the Interior Takos Makris and his wife Doxoula (whom he described as Karamanlis's niece) along with then Deputy Minister of Defense George Themelis were

informers during the Nazi occupation of Greece. Merten alleged that

Karamanlis and Makris were rewarded for their services with a business

in Thessaloniki which belonged to a Greek Jew sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp. He also alleged that he had pressured Karamanlis and Makris grant amnesty and release him from prison. Karamanlis

rejected the claims as unsubstantiated and absurd, and accused Merten

of attempting to extort money from him prior to making the statements.

Although Karamanlis never pressed charges against Merten,

charges were pressed in Greece against Der Spiegel by

Takos and Doxoula Makris and Themelis, and the magazine was found

guilty for slander in 1963. Merten's

accusations against Karamanlis were never corroborated in a court of

law. Karamanlis

as early as 1958 pursued an aggressive policy toward Greek membership

in the EEC. He considered Greece's entry into the EEC a personal dream

because he saw it as the fulfillment of what he called "Greece's

European Destiny". He personally lobbied European leaders, such as Germany's Konrad Adenauer and France's Charles de Gaulle followed by two years of intense negotiations with Brussels. His

intense lobbying bore fruit and on 9 July 1961 his government and the

Europeans signed the protocols of Greece's Treaty of Association with

the European Economic Community (EEC). The signing ceremony in Athens

was attended by top government delegations from the six-member bloc of

Germany, France, Italy, Belgium, Luxemburg and the Netherlands, a

precursor of the European Union. Economy Minister Aristidis Protopapadakis and Foreign Minister Evangelos Averoff were also present. German Vice-Chancellor Ludwig Erhard and Belgian Foreign Minister Paul-Henri Spaak, a European Union pioneer and a Karlspreis winner like Karamanlis, were among the European delegates. This

had the profound effect of ending Greece's economic isolation and

breaking its political and economic dependence on US economic and

military aid, mainly through NATO. Greece

became the first European country to acquire the status of associate

member of the EEC outside the six nation EEC group. In November 1962

the association treaty came into effect and envisaged the country's

full membership at the EEC by 1984, after the gradual elimination of

all Greek tariffs on EEC imports. A

financial protocol clause included in the treaty provided for loans to

Greece subsidised by the community of about $300 million between 1962

and 1972 to help increase the competitiveness of the Greek economy in

anticipation of Greece's full membership. The Community's financial aid

package as well as the protocol of accession were suspended during the

1967-74 junta years and Greece was expelled from the EEC. As well, during the dictatorship, Greece resigned its membership in the Council of Europe fearing embarrassing investigations by the Council, following torture allegations. Soon after returning to Greece during metapolitefsi Karamanlis reactivated his push for the country's full EEC membership in 1975 citing political and economic reasons. Karamanlis

was convinced that Greece's membership in the EEC would ensure

political stability in a nation having just undergone a transition from

dictatorship to Democracy. In

May 1979 he signed the full treaty of accession. Greece became the

tenth member of the EEC on 1 January 1981 three years earlier than the

original protocol envisioned and despite the freezing of the treaty of

accession during the junta (1967–1974) In the 1961 elections, the National Radical Union won 50.80 percent of the popular vote. On October 31, George Papandreou stated

that the electoral results were due to widespread vote-rigging and

fraud. Karamanlis replied electoral fraud, to the extent that it

happened, was masterminded by the Palace. Political tension escalated,

as Papandreou refused to recognize the Karamanlis government. On 14

November 1961 he initiated an "unrelenting struggle" ("ανένδοτο αγώνα")

against Karamanlis. Tension

between Karamanlis and the Palace escalated even further as Karamanlis

vetoed fundraising initiatives undertaken by Queen Frederika. On 17 June 1963 Karamanlis resigned the premiership after a disagreement with King Paul of Greece, and spent four months abroad. In the meantime the country was in turmoil following the assassination of Dr. Grigoris Lambrakis, a leftist member of Parliament, by right-wing extremists during a pro-peace demonstration in Thessaloniki. The opposition parties castigated Karamanlis as a moral accomplice to the assassination. In the 1963 election the National Radical Union, under his leadership, was defeated by the Center Union under George Papandreou. Disappointed with the result, Karamanlis fled Greece under the name Triantafyllides. He spent the next 11 years in self-imposed exile in Paris, France. Karamanlis was succeeded by Panagiotis Kanellopoulos as the ERE leader. On 21 April 1967, constitutional order was usurped by a coup d'état led by officers around Colonel George Papadopoulos.

The King accepted to swear in the military-appointed government as the

legitimate government of Greece, but launched an abortive counter-coup

to overthrow the junta eight months later. Constantine and his family then fled the country. Following

the invasion of Cyprus by the Turks, the dictators finally abandoned

Ioannides and his disastrous policies. On 23 July 1974, President

Phaedon Gizikis called a meeting of old guard politicians, including Panagiotis Kanellopoulos, Spiros Markezinis, Stephanos Stephanopoulos, Evangelos Averoff and

others. The heads of the armed forces also participated in the meeting.

The agenda was to appoint a national unity government that would lead

the country to elections. Former

Prime Minister Panagiotis Kanellopoulos was originally suggested as the

head of the new interim government. He was the interim Prime Minister

originally deposed by the dictatorship in 1967 and a distinguished

politician who had repeatedly criticized Papadopoulos and his

successor. Raging battles were still taking place in Cyprus' north when

Greeks took to the streets in all the major cities, celebrating the

junta's decision to relinquish power before the war in Cyprus could

spill all over the Aegean. But talks in Athens were going nowhere with Gizikis' offer to Panagiotis Kanellopoulos to form a government. Nonetheless, after all the other politicians departed without reaching a decision, Evangelos Averoff remained

in the meeting room and further engaged Gizikis. He insisted that

Karamanlis was the only political personality who could lead a

successful transition government, taking into consideration the new

circumstances and dangers both inside and outside the country. Gizikis

and the heads of the armed forces initially expressed reservations, but

they finally became convinced by Averoff's arguments. Admiral

Arapakis was the first, among the participating military leaders, to

express his support for Karamanlis. After

Averoff's decisive intervention, Gizikis decided to invite Karamanlis

to assume the premiership. Throughout his stay in France, Karamanlis

was a vocal opponent of the Regime of the Colonels, the military junta that

seized power in Greece in April 1967. Now he was called to end his self

imposed exile and restore Democracy. Athenians in the thousands went to the airport to greet him. Karamanlis was sworn-in as Prime Minister under President pro tempore Phaedon

Gizikis who remained in power in the interim, till December 1974, for

legal continuity reasons until a new constitution could be enacted

during metapolitefsi, and was subsequently replaced by duly elected

President Michail Stasinopoulos. During the inherently unstable first weeks of the metapolitefsi,

Karamanlis was forced to sleep aboard a yacht watched over by a

destroyer for the fear of a new coup. Karamanlis attempted to defuse

the tension between Greece and Turkey, which were on the brink of war over the Cyprus crisis, through the diplomatic route. Two successive conferences in Geneva, where the Greek government was represented by George Mavros, failed to avert a full-scale invasion and occupation of 37 percent of Cyprus by Turkey on 14 August 1974. The

steadfast process of transition from military rule to a pluralist

democracy proved successful. During this transition period of themetapolitefsi, Karamanlis legalized the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) that was banned decades ago. The legalization of the communist party was considered by many as a gesture of political inclusionism and rapprochement. At the same time he also freed all political prisoners and pardoned all political crimes against the junta. Following

through with his reconciliation theme he also adopted a measured

approach to removing collaborators and appointees of the dictatorship

from the positions they held in government bureaucracy, and declared that free elections would be held in November 1974, four months after the collapse of the Regime of the Colonels. In the 1974 elections, Karamanlis with his newly formed conservative party, named New Democracy obtained a massive parliamentary majority and was elected Prime Minister. The elections were soon followed by the 1974 plebiscite on the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of the Hellenic Republic,

the televised 1975 trials of the former dictators (who received death

sentences for high treason and mutiny that were later commuted to life

incarceration) and the writing of the 1975 constitution. In 1977, New Democracy again won the elections, and Karamanlis continued to serve as Prime Minister until 1980. Under Karamanlis's premiership, his government undertook numerous nationalizations in several sectors, including banking and transportation. Karamanlis's policies of economic statism, which fostered a large state-run sector, have been described by many as socialmania. Following his signing of the Accession Treaty with the European Economic Community (now the European Union) in 1979, Karamanlis relinquished the Premiership and was elected President of the Republic in 1980 by the Parliament, and

in 1981 he oversaw Greece's formal entry into the European Economic

Community as its tenth member. He served until 1985 then resigned and

was succeeded by Christos Sartzetakis. In

1990 he was re-elected President by a conservative parliamentary

majority (under the conservative government of then Prime Minister Konstantinos Mitsotakis) and served until 1995, when he was succeeded by Kostis Stephanopoulos. Karamanlis

retired in 1995, at the age of 88, having won 5 parliamentary

elections, and having spent 14 years as Prime Minister, 10 years as

President of the Republic, and a total of more than sixty years in

active politics. For his long service to democracy and as a pioneer of

European integration from the earliest stages of the European Union,

Karamanlis was awarded one of the most prestigious European prizes, the Karlspreis, in 1978. He bequeathed his archives to the Konstantinos Karamanlis Foundation, a conservative think tank he had founded and endowed.

Karamanlis died after a short illness in 1998, at the age of 91.