<Back to Index>

- Astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille, 1713

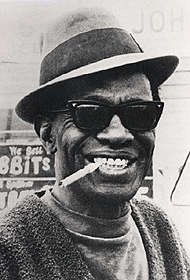

- Bluesman Sam "Lightnin'" Hopkins, 1912

- President of Poland Stanisław Wojciechowski, 1869

Sam "Lightnin’" Hopkins (March 15, 1912 — January 30, 1982) was a country blues guitarist, from Houston, Texas, United States.

Born in Centerville, Texas, Hopkins' childhood was immersed in the sounds of the blues and he developed a deeper appreciation at the age of 8 when he met Blind Lemon Jefferson at a church picnic in Buffalo, Texas. That day, Hopkins felt the blues was "in him" and went on to learn from his older (somewhat distant) cousin, country blues singer Alger "Texas" Alexander. Hopkins began accompanying Blind Lemon Jefferson on guitar in informal church gatherings. Jefferson supposedly never let anyone play with him except for young Hopkins, who learned much from and was influenced greatly by Blind Lemon Jefferson thanks to these gatherings. In the mid 1930s, Hopkins was sent to Houston County Prison Farm for an unknown offence. In the late 1930s Hopkins moved to Houston with Alexander in an unsuccessful attempt to break into the music scene there. By the early 1940s he was back in Centerville working as a farm hand.

Hopkins took a second shot at Houston in 1946. While singing on Dowling St. in Houston's Third Ward (which would become his home base) he was discovered by Lola Anne Cullum from the Los Angeles based record label, Aladdin Records. She convinced Hopkins to travel to L.A. where he accompanied pianist Wilson Smith. The duo recorded twelve tracks in their first sessions in 1946. An Aladdin Records executive decided the pair needed more dynamism in their names and dubbed Hopkins "Lightnin'" and Wilson "Thunder". Hopkins recorded more sides for Aladdin in 1947 but soon grew homesick. He returned to Houston and began recording for the Gold Star Records label. During the late 40s and 1950s Hopkins rarely performed outside Texas. However, he recorded prolifically. Occasionally traveling to the Mid-West and Eastern United States for recording sessions and concert appearances. It has been estimated that he recorded between 800 and 1000 songs during his career. He performed regularly at clubs in and around Houston, particularly in Dowling St. where he had first been discovered. He recorded his hits "T-Model Blues" and "Tim Moore's Farm" at Sugar Hill Recording Studios in Houston. By the mid to late 1950s his prodigious output of quality recordings had gained him a following among African Americans and blues music aficionados.

In 1959 Hopkins was contacted by folklorist Mack McCormick who hoped to bring him to the attention of the broader musical audience which was caught up in the folk revival. McCormick presented Hopkins to integrated audiences first in Houston and then in California. Hopkins debuted at Carnegie Hall on October 14, 1960 appearing alongside Joan Baez and Pete Seeger performing the spiritual Oh, Mary Don’t You Weep. In 1960, he signed to Tradition Records. Solid recordings followed including his masterpiece song "Mojo Hand" in 1960.

By the early 1960s Lightnin' Hopkins reputation as one of the most compelling blues performers was cemented. He had finally earned the success and recognition which were overdue. In 1968, Hopkins recorded the album Free Form Patterns backed by the rhythm section of psychedelic rock band the 13th Floor Elevators. Through the 1960s and into the 1970s Hopkins released one or sometimes two albums a year and toured, playing at major folk festivals and at folk clubs and on college campuses in the U.S. and internationally. He travelled widely in the United States, and overcame his fear of flying to join the 1964 American Folk Blues Festival; visit Germany and the Netherlands 13 years later; and play a six-city tour of Japan in 1978.

Filmmaker Les Blank captured the Texas troubadour's informal lifestyle most vividly in his acclaimed 1967 documentary, The Blues Accordin' to Lightnin' Hopkins.

Houston's poet-in-residence for 35 years, Hopkins recorded more albums than any other bluesman.

Hopkins died of esophageal cancer in Houston in 1982 at the age of 69.

A statue of Hopkins stands in Crockett, Texas. Hopkins' style was born from spending many hours playing informally without a backing band. His distinctive fingerstyle playing often included playing, in effect, bass, rhythm, lead, percussion, and vocals, all at the same time. He played both "alternating" and "monotonic" bass styles incorporating imaginative, often chromatic turnarounds and

single note lead lines. Tapping or slapping the body of his guitar

added rhythmic accompaniment. Much of Hopkins' music follows the

standard 12-bar blues template but his phrasing was very free and loose. Many of his songs were in the talking blues style,

but he was a powerful and confident singer. Lyrically his songs

chronicled the problems of life in the segregated south, bad luck in

love and other usual subjects of the blues idiom. He did however deal

with these subjects with humor and good nature. Many of his songs are

filled with double entendres and he was known for his humorous introductions. Some of his songs were of warning and sour prediction like Fast Life Woman: