<Back to Index>

- Physicist Jean Frédéric Joliot-Curie, 1900

- Painter Charles Marion Russell, 1864

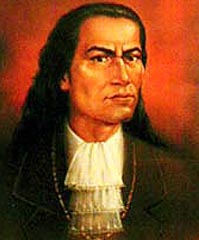

- Peru's Revolutionary Túpac Amaru II, 1742

Túpac Amaru II (José Gabriel Túpac Amaru; March 19, 1742 Tinta, Cusco, Peru – executed in Cusco May 18, 1781) was the leader of an indigenous uprising in 1780 against the Spanish in Peru. Although unsuccessful, he later became a mythical figure in the Peruvian struggle for independence and indigenous rights movement and an inspiration to a myriad of causes in Peru. He should not be confused with Túpac Katari who led a similar uprising in the region now called Bolivia at the same time.

Tupac Amaru II was born José Gabriel Condorcanqui in Tinta, in the province of Cuzco, and received a Jesuit education at the San Francisco de Borja School, although he maintained a strong identification with the indian population. He was a mestizo who claimed to be a direct descendant of the last Incan ruler Túpac Amaru. He had been honored by the Spanish authorities of Peru with the title of Marquis of Oropesa, a position that allowed him some voice and political leverage during Spanish rule. Between 1741 and 1780 Amaru II went into litigation with the Betancur family over the right of succesion of the Marquisate of Oropesa and lost the case. In 1760, he married Micaela Bastidas Puyucahua of Afro-Peruvian and Indigenous descent. Condorcanqui inherited the caciqueship, or hereditary chiefdom of Tungasuca and Pampamarca from his older brother, governing on behalf of the Spanish governor.

While the Spanish trusteeship labor system, or encomienda, had been abolished in 1720, most Indians at the time living in the Andean region of what is now Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia, who made up nine tenths of the population at the time, were still pushed into forced labor for what was legally labeled as public work projects. However, most natives worked under the supervision of a master either tilling soil, mining or working in textile mills. What little wage that was acquired by workers was heavily taxed and cemented Indian indebtedness to Spanish masters. The Catholic Church also had a hand in extorting these natives through collections for saints, masses for the dead, domestic and parochial work on certain days, forced gifts, etc. Those fortunate enough not to be subjugated to forced labor were subject to the Spanish provincial governors, or corregidores, who also heavily taxed any free natives, similarly ensuring their financial instability.

Condorcanqui interest in the Indian cause had been spurred by the re-reading of the Royal Commentaries of the Incas,

a romantic and heroic account of the history and culture of the ancient

Incas. The book was outlawed at the time by the Lima viceroy for fear

of it inspiring renewed interest in the lost Inca culture and inciting

rebellion.

The marquis' native pride coupled with his hate for the oppressors of

his people, caused José Gabriel to sympathize and frequently

petition for the improvement of Indian labor in the mills, farms and

mines; even using his own wealth to help alleviate the taxes and

burdens of the natives. After many of his requests for the alleviation

of the native Indian’s conditions fell to deaf ears, Condorcanqui

decided to organize a rebellion. He began to stall on collecting

reparto debts and tribute payments, for which the Tintan corregidor and

governor Antonio de Arriaga threatened

him with death. Feeling that his time was ripe, Condorcanqui changed

his name to Tupac Amaru II and declared his lineage to the last Incan

ruler Felipe Tupac Amaru. Túpac Amaru II's rebellion was

one of many indigenous Peruvian uprisings in the latter half of the

18th century, and its birth was marked by the capturing and killing of

Tintan corregidor and

governor Antonio de Arriaga on November 4, 1780. The event unfolded

after both Tupac Amaru II and the governor Arriaga attended a banquet

hosted by a priest. When

governor Arriaga left the party in a drunken state, Tupac Amaru II and

several of his allies captured him and forced him to write letters to a

large number of Hispanics and curacas. When about 200 of them gathered

within the next few days, Tupac Amaru II surrounded them with

approximately 4000 Indians. Claiming that he was acting under direct

Spanish royal orders, Amaru II gave Arriaga’s slave Antonio Oblitas the

privilege of executing him. A

platform in the middle of a local town plaza was erected, and the

initial attempt at hanging the corregidor failed after the noose had

snapped. He then ran for his life to try and reach a nearby church, but

was not quick enough to escape being successfully hanged at the second

attempt. After

the execution of the corregidor, Amaru II began his insurrection. He

organized an army of six thousand Indians who had abandoned their work

to join the revolt. As they marched towards Cuzco, the rebels occupied

the provinces of Quispicanchis, Tinta, Cotabambas, Calca, and Chumbivilcas. After years of living under oppression, the rebels looted the Hispanic houses and killed their Spanish oppressors. In

November 18, 1780, Cuzco dispatched over 1,300 Hispanic and Indian

loyalist troops. The two opposing forces clashed in the town of

Sangarara. (This battle would be recorded later as the Battle of Sangarara.)

It was an absolute victory for Amaru II and his native Indian rebels;

all of the 578 Hispanic soldiers were killed and the rebels took

possession of their weapons and supplies. The victory however, also

came with a price. The battle revealed that Amaru II was unable to

fully control his rebel followers, as they viciously slaughtered

without direct orders. Reports of such violence and the rebels'

insistence on the death of Hispanics eliminated any chances for a

support by the Creole class. The

victory achieved at Sangarara would be followed by a string of defeats.

The most critical defeat came in Amaru II’s failure to capture Cuzco,

which was fortified by a combined troop of loyalist Indians and

reinforcements from Lima. After subsequent skirmishes around the surrounding region, Amaru II and his rebels became surrounded between Tinta and Sangarara. A betrayal by two of his officers, colonel Ventura Landaeta and captain Francisco Cruz, sealed Amaru II’s defeat and capture.

Amaru

II was sentenced to a cruel execution. He was forced to bear witness to

the execution of his wife, his eldest son Hipólito, his uncle

Francisco, his brother-in-law Antonio Bastidas, and some of his

captains before his own death. He was sentenced to be tortured and

beheaded. Preceding his own beheading, Túpac Amaru II had his

tongue cut out and his limbs tied to four horses. Tupac Amaru was too

strong to be killed in this fashion. Due to this, the method chosen to

kill him was to behead him (as part of a failed attempt to quarter him)

on the main plaza in Cuzco, in the same place his

great-great-great-grandfather the last Inca Tupac Amaru had

been beheaded. When the revolt continued, the Spaniards executed the

remainder of his family, except his 12-year-old son Fernando, who had

been condemned to die with him, but was instead imprisoned in Spain for

the rest of his life. It is not known if any members of the Inca royal

family survived this final purge. Amaru's body parts were strewn across

the towns loyal to him, his houses were demolished, their sites strewn

with salt, his goods confiscated, his relatives declared infamous, and

all documents relating to his descent burnt. At

the same time, on May 18, 1781, Incan clothing and cultural traditions,

and self-identification as "Inca" were outlawed, along with other

measures to convert the population to Spanish culture and government

until Peru's independence as a republic. However, even after the death

of Amaru, Indian revolt still overtook much of Southern Peru ,

Bolivia and Argentina, as Indian revolutionaries captured Spanish towns

and beheaded many inhabitants. In one instance, an Indian army under

rebel leader Túpac Katari overtook the city of La Paz for

one hundred and nine days before Argentinean troops stepped in to

relieve the city. While Tupac Amaru II's rebellion was not a success,

it marked the first large-scale rebellion in the Spanish colonies and

inspired the revolt of many native Indians and mestizos in the

surrounding area. The rebellion gave the Natives a new state of mind,

and set the stage for their support of Bolivar forty years later. They

were now willing to join forces with anyone who opposed the hated

Spanish. For all his sacrifice he was proclamated King of America.