<Back to Index>

- Philosopher, Polymath and Writer Rabindranath Tagore, 1861

- Composer Johannes Brahms, 1833

- President of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Josip Broz Tito, 1892

Josip Broz Tito (Cyrillic script: Jосип Броз Тито; 7 or 25 May 1892 – 4 May 1980) was a Yugoslav revolutionary and statesman. He was Secretary-General (later President) of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (1939–80), and went on to lead the World War II Yugoslav resistance movement, the Yugoslav Partisans (1941–45). After the war, he was the authoritarian Prime Minister (1943–63) and later President (1953–80) of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY). From 1943 to his death in 1980, he held the rank of Marshal of Yugoslavia, serving as the supreme commander of the Yugoslav military, the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA).

Tito

was the chief architect of the "second Yugoslavia", a socialist

federation that lasted from World War II until 1991. Despite being one

of the founders of Cominform,

he was also the first (and the only successful) Cominform member to

defy Soviet hegemony. A backer of independent roads to socialism

(sometimes referred to as "national communism" or "Titoism"), he was one of the main founders and promoters of the Non-Aligned Movement,

and its first Secretary-General. As such, he supported the policy of

nonalignment between the two hostile blocs in the Cold War. Josip Broz was born in Kumrovec in the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia, a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He was the seventh child of Franjo and Marija Broz. His father, Franjo Broz, was a Croat, while his mother Marija (born Javeršek) was a Slovene. After spending part of his childhood years with his maternal grandfather in the village of Podsreda, in 1900 he entered the primary school (four classes) in Kumrovec, he failed the 2nd grade and graduated in 1905. In 1907, moving out of the rural environment, Broz started working as a machinist's apprentice in Sisak. There, he became aware of the labor movement and celebrated 1 May - Labour Day for the first time. In 1910, he joined the union of metallurgy workers and at the same time the Social-Democratic Party of Croatia and Slavonia. Between 1911 and 1913, Broz worked for shorter periods in Kamnik, Cenkovo, Munich, and Mannheim, where he worked for the Benz automobile factory; he then went to Wiener Neustadt, Austria, and worked as a test driver for Daimler. In the autumn of 1913, he was drafted into the Austro-Hungarian Army.

He was sent to a school for non-commissioned officers and became a

sergeant, serving in the 25th Croatian Regiment based in Zagreb. In May 1914, Broz won a silver medal at an army fencing competition in Budapest. At the outbreak of World War I in 1914, he was sent to Ruma, where he was arrested for anti-war propaganda and imprisoned in the Petrovaradin fortress. In January 1915, he was sent to the Eastern Front in Galicia to

fight against Russia. He distinguished himself as a capable soldier and

was recommended for military decoration, becoming the youngest Sergeant Major in the Austro-Hungarian Army. On Easter 25 March 1915, while in Bukovina, he was seriously wounded and captured by the Russians. After thirteen months at the hospital, Broz was sent to a work camp in the Ural Mountains where

prisoners selected him for their camp leader. In February 1917,

revolting workers broke into the prison and freed the prisoners. Broz

subsequently joined a Bolshevik group. In April 1917, he was arrested again but managed to escape and participate in the July Days demonstrations in Petrograd (Saint Petersburg) on 16–17 July 1917. On his way to Finland, Broz was caught and imprisoned in the Petropavlovsk fortress for three weeks. He was again sent to Kungur, but escaped from the train. He hid out with a Russian family in Omsk, Siberia where he met his future wife Pelagija Belousova. After the October Revolution, he joined a Red Guard unit in Omsk. Following a White counteroffensive, he fled to Kirgiziya and subsequently returned to Omsk, where he married Belousova. In the spring of 1918, he joined the Yugoslav section of the Russian Communist Party.

By June of the same year, Broz left Omsk to find work and support his

family, and was employed as a mechanic near Omsk for a year. In January

1920, he and his wife made a long and difficult journey home to

Yugoslavia where he arrived in September. Upon his return, Broz joined the Communist Party of Yugoslavia. The CPY's influence on the political life of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was

growing rapidly. In the 1920 elections the Communists won 59 seats in

the parliament and became the third strongest party. Winning numerous

local elections, they even gained a stronghold in the second-largest

city of Zagreb, electing Svetozar Delić for

mayor. The King's regime, however, would not tolerate the CPY and

declared it illegal. During 1920 and 1921 all Communist-won mandates

were nullified. Broz continued his work underground despite pressure on

Communists from the government. As 1921 began he moved to Veliko Trojstvo near Bjelovar and found work as a machinist. In 1925, Broz moved to Kraljevica where

he started working at a shipyard. He was elected as a union leader and

a year later he led a shipyard strike. He was fired and moved to

Belgrade, where he worked in a train coach factory in Smederevska Palanka.

He was elected as Workers Commissary but was fired as soon as his CPY

membership was revealed. Broz then moved to Zagreb, where he was

appointed secretary of Metal Workers Union of Croatia. In 1928, he

became the Zagreb Branch Secretary of the CPY. In the same year he was

arrested, tried in court for his illegal communist activities, and sent

to jail. During his five years at Lepoglava prison he met Moša Pijade who became his ideological mentor. After his release, he lived incognito and assumed a number of noms de guerre, among them "Walter" and "Tito". In 1934 the Zagreb Provincial Committee sent Tito to Vienna where

the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia had sought

refuge. He was appointed to the Committee and started to appoint allies

to him, among them Edvard Kardelj, Milovan Djilas, Aleksandar Rankovic, and Boris Kidric. In 1935, Tito traveled to the Soviet Union, working for a year in the Balkan section of Comintern. He was a member of the Soviet Communist Party and the Soviet secret police (NKVD). In 1936, the Comintern sent "Comrade Walter" (i.e. Tito) back to Yugoslavia to purge the Communist Party there. In 1937, Stalin had the Secretary-General of the CPY, Milan Gorkić, murdered in Moscow. Subsequently Tito was appointed Secretary-General of the still-outlawed CPY. On 6 April 1941, German, Italian, and Hungarian forces launched an invasion of Yugoslavia.

On April 10, Tito responded by forming a Military Committee within the

Central Committee of the Yugoslav Communist Party. Attacked from all

sides, the armed forces of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia quickly crumbled. On 17 April, after King Peter II and

other members of the government fled the country, the remaining

representatives of the government and military met with the German

officials in Belgrade. They quickly agreed to end military resistance.

On May 1, Tito issued a pamphlet calling on the people to unite in a

battle against the occupation. On 4 July 1941, after Germany launched the invasion of the Soviet Union - 22 June 1941 -- (Operation Barbarossa), Tito

called a Central committee meeting which named him military commander

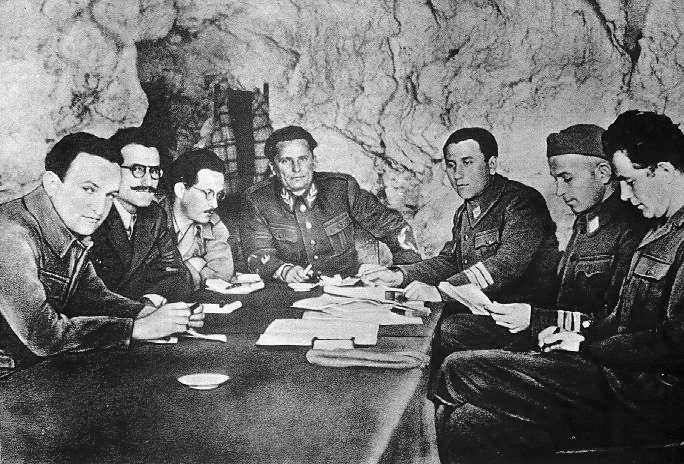

and issued a call to arms. That same day, Yugoslav Partisans formed the 1st Sisak Partisan Detachment, often named the first armed resistance unit in Europe (mostly consisting of Croats from the nearby city). Despite conflicts with the collaborating Chetnik movement, Tito's Partisans succeeded in liberating territory, such as the "Republic of Užice". In these liberated territories, the Partisans organized People's Committees to act as civilian government. The Anti-Fascist Council of National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ), which convened in Bihać on 26 November 1942 and in Jajce on

29 November 1943, was a representative body established by the

resistance in which Tito played a leading role. In the two sessions,

the resistance representatives established the basis for post-war

organization of the country, deciding on a federation of the Yugoslav

nations. In Jajce, Tito was named President of the National Committee

of Liberation. On

4 December 1943, while most of the country was still occupied by the

Axis, Tito proclaimed a provisional democratic Yugoslav government. However,

with the growing possibility of an Allied invasion in the Balkans, the

Axis began to divert more resources to the destruction of the Partisans

main force and its high command. This meant, among other things, a

concerted German effort to capture Josip Broz Tito personally. The

Germans came close to capturing or killing Tito on at least three

occasions: during the 1943 Battle of Neretva (Fall Weiss); during the subsequent Battle of Sutjeska (Fall Schwarz), in which he was wounded on 9 June, and on 25 May 1944, when he barely managed to evade the Germans after the Raid on Drvar (Operation Rösselsprung), anairborne assault outside his Drvar headquarters in Bosnia. After the Partisans managed to endure and avoid these intense Axis attacks between January and June 1943, and the extent of Chetnik collaboration became evident, Allied leaders switched their support from Draža Mihailović to Tito. King Peter II, American President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill joined Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin in officially recognizing Tito and the Partisans at the Tehran Conference.

This resulted in Allied aid being parachuted behind Axis lines to

assist the Partisans. On 17 June 1944 on the Dalmatian island of Vis, the Treaty of Vis (Viški sporazum) was signed in an attempt to merge Tito's government (the AVNOJ) with the government in exile of King Peter II. This treaty was also known as the Tito-Šubašić Agreement. As the leader of the Yugoslav forces, Tito was now personally a target for the Axis forces in occupied Yugoslavia. The Partisans were supported directly by Allied airdrops to their headquarters, with Brigadier Fitzroy Maclean playing a significant role in the liaison missions. The RAF Balkan Air Force was formed in June 1944 to control operations that were mainly aimed at aiding his forces. On 28 September 1944, the Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (TASS)

reported that Tito signed an agreement with the USSR allowing

"temporary entry of Soviet troops into Yugoslav territory" which

allowed the Red Army to

assist in operations in the northeastern areas of Yugoslavia. With

their strategic right flank secured by the Allied advance, the Partisans prepared and executed a massive general offensive which succeeded in breaking

through German lines and forcing a retreat beyond Yugoslav borders.

After the Partisan victory and the end of hostilities in Europe, all

external forces were ordered off Yugoslav territory. On 7 March 1945, the provisional government of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia (Demokratska Federativna Jugoslavija, DFY) was assembled in Belgrade by

Josip Broz Tito, while the provisional name allowed for either a

republic or monarchy. This government was headed by Tito as provisional

Yugoslav Prime Minister and included representatives from the royalist government-in-exile, among others Ivan Šubašić.

In accordance with the agreement between resistance leaders and the

government-in-exile, post-war elections were held to determine the form of government. In November 1945, Tito's pro-republican People's Front, led by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, won the elections with an overwhelming majority, the vote having been boycotted by monarchists. During

the period, Tito evidently enjoyed massive popular support due to being

generally viewed by the populace as the liberator of Yugoslavia. The

Yugoslav administration in the immediate post-war period managed to

unite a country that had been severely affected by ultra-nationalist

upheavals and war devastation, while successfully suppressing the

nationalist sentiments of the various nations in favor of tolerance,

and the common Yugoslav goal. After the overwhelming electoral victory,

Tito was confirmed as the Prime Minister and the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the DFY. The country was soon renamed the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia (FPRY) (later finally renamed into Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, SFRY). On 29 November 1945, King Peter II was formally deposed by the Yugoslav Constituent Assembly. The Assembly drafted a new republican constitution soon afterwards. Yugoslavia organized an army from the Partisan movement, the Yugoslav People's Army (Jugoslavenska narodna armija, or JNA) which was, for a period, considered the fourth strongest in Europe. The State Security Administration (Uprava državne bezbednostil sigurnosti/ varnosti, UDBA) was also formed as the new secret police, along with a security agency, the Department of People's Security (Organ Zaštite Naroda (Armije),

OZNA). Yugoslav intelligence was charged with imprisoning and bringing

to trial large numbers of Nazi collaborators; controversially, this

included Catholic clergymen due to the widespread involvement of Croatian Catholic clergy with the Ustaša regime. Draža Mihailović was found guilty of collaboration, high treason and war crimes and was subsequently executed by firing squad in July 1946. Prime Minister Josip Broz Tito met with the president of the Bishops' Conference of Yugoslavia, Aloysius Stepinac on

4 June 1945, two days after his release from imprisonment. The two

could not reach an agreement on the state of the Catholic Church. Under

Stepinac's leadership, the bishops' conference released a letter

condemning alleged Partisan war crimes in September, 1945. The

following year Stepinac was arrested and put on trial. In October 1946,

in its first special session for 75 years, the Vatican excommunicated

Tito and the Yugoslav government for sentencing Stepinac to 16 years in

prison on charges of assisting Ustaše terror and of supporting forced conversions of Serbs to Catholicism. Stepinac received preferential treatment in recognition of his status and

the sentence was soon shortened and reduced to house-imprisonment, with

the option of emigration open to the archbishop. At the conclusion of

the "Informbiro period", reforms rendered Yugoslavia considerably more

religiously liberal than the Eastern Bloc states. In

the first post war years Tito was widely considered a communist leader

very loyal to Moscow, indeed, he was often viewed as second only to

Stalin in the Eastern Bloc. Yugoslav forces shot down American aircraft

flying over Yugoslav territory, and relations with the West were

strained. In fact, Stalin and Tito had an uneasy alliance from the

start, with Stalin considering Tito too independent. Unlike

the other new communist states in east-central Europe, Yugoslavia

liberated itself from Axis domination, with limited direct support from

the Red Army.

Tito's leading role in liberating Yugoslavia not only greatly

strengthened his position in his party and among the Yugoslav people,

but also caused him to be more insistent that Yugoslavia had more room

to follow its own interests than other Bloc leaders who had more

reasons (and pressures) to recognize Soviet efforts in helping them

liberate their own countries from Axis control. This had already led to

some friction between the two countries before World War II was

even over. Although Tito was formally an ally of Stalin after World War

II, the Soviets had set up a spy ring in the Yugoslav party as early as

1945, giving way to an uneasy alliance. In the immediate aftermath of World War II, there occurred several armed incidents between Yugoslavia and the Western Allies. Following the war, Yugoslavia acquired the Italian territory of Istria as well as the cities of Zadar and Rijeka. Yugoslav leadership was looking to incorporate Trieste into

the country as well, which was opposed by the Western Allies. This led

to several armed incidents, notably air attacks of Yugoslav fighter

planes on U.S. transport aircraft, causing bitter criticism from the west. From 1945 to 1948, at least four US aircraft were shot down. Stalin

was opposed to these provocations, as he felt the USSR unready to face

the West in open war so soon after the losses of World War II. In

addition, Tito was openly supportive of the Communist side in the Greek Civil War, while Stalin kept his distance, having agreed with Churchill not

to pursue Soviet interests there. In 1948, motivated by the desire to

create a strong independent economy, Tito modeled his economic

development plan independently from Moscow, which resulted in a

diplomatic escalation followed by a bitter exchange of letters. The Soviet answer on 4 May admonished Tito and the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (CPY)

for failing to admit and correct its mistakes, and went on to accuse

them of being too proud of their successes against the Germans,

maintaining that the Red Army had saved them from destruction. Tito's

response on 17 May suggested that the matter be settled at the meeting

of the Cominform to be held that June. However, Tito did not attend the

second meeting of the Cominform,

fearing that Yugoslavia was to be openly attacked. At this point the

crisis nearly escalated into an armed conflict, as Hungarian and Soviet

forces were massing on the northern Yugoslav frontier. On

28 June, the other member countries expelled Yugoslavia, citing

"nationalist elements" that had "managed in the course of the past five

or six months to reach a dominant position in the leadership" of the

CPY. The expulsion effectively banished Yugoslavia from the

international association of socialist states, while other socialist

states of Eastern Europe subsequently underwent purges of alleged

"Titoists". Stalin took the matter personally – for once, and

attempted, unsuccessfully, to assassinate Tito on several occasions. In

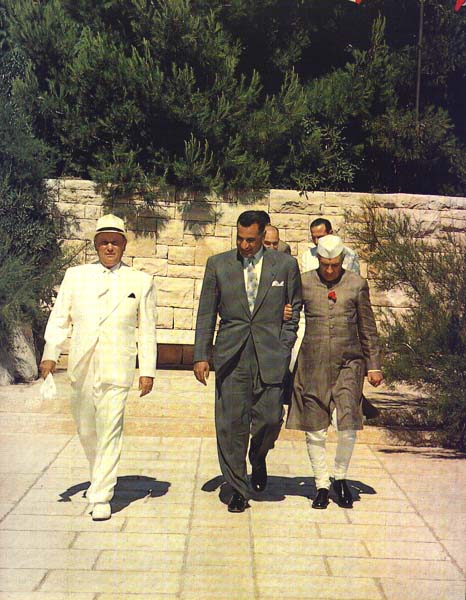

a correspondence between the two leaders, Tito openly wrote: However, Tito used the estrangement from the USSR to attain US aid via the Marshall Plan, as well as to involve Yugoslavia in the Non-Aligned Movement,

in which he assured a leading position for Yugoslavia. The event was

significant not only for Yugoslavia and Tito, but also for the global

development of socialism, since it was the first major split between

Communist states, casting doubt on Comintern's claims for socialism to

be a unified force that would eventually control the whole world, as

Tito became the first (and the only successful) socialist leader to

defy Stalin's leadership in the COMINFORM. This rift with the Soviet Union brought Tito much international recognition, but also triggered a period of instability often referred to as the Informbiro period. Tito's form of communism was labeled "Titoism" by Moscow, which encouraged purges against suspected "Titoites'" throughout the Eastern bloc. As a result of the split with the USSR the Yugoslavian government established a prison camp on the Croatian island of Goli Otok for

suspected pro-Soviet enemies of Tito and the CPY regime. In 1949, the

entire island was officially made into a high-security, top secret

prison and labor camp. Until 1956, throughout the Informbiro period, it

was used to incarcerate political prisoners. They included known and

alleged Stalinists, but also other Communist Party members or even

regular citizens accused of exhibiting any sort of sympathy or leanings

towards the Soviet Union. Some 10,000 people went through the camp.

There are many witness accounts of brutality by prison guards, officers

and staff. On 26 June 1950, the National Assembly supported a crucial bill written by Milovan Đilas and Tito about "self-management" (samoupravljanje): a type of independent socialism that experimented with profit sharing with

workers in state-run enterprises. On 13 January 1953, they established

that the law on self-management was the basis of the entire social

order in Yugoslavia. Tito also succeeded Ivan Ribar as

the President of Yugoslavia on 14 January 1953. After Stalin's death

Tito rejected the USSR's invitation for a visit to discuss

normalization of relations between the two nations. Nikita Khrushchev and

Nikolai Bulganin visited Tito in Belgrade in 1955 and apologized for

wrongdoings by Stalin's administration. Tito visited the USSR in 1956, which signaled to the world that animosity between Yugoslavia and USSR was easing. However,

the relationship between the USSR and Yugoslavia would reach another low in the late 1960s. On 7 April 1963, the country changed its official name to the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Reforms encouraged private enterprise and greatly relaxed restrictions on freedom of speech and religious expression. Broz subsequently went on a tour of the Americas. In Chile, two government ministers resigned over his visit to that country. Broz

spoke at the United Nations General Assembly in New York, with his

visit being protested by both Croat and Serb emigrants. US Senator Thomas Dodd subsequently

said Broz had "bloodied hands". In 1966 an agreement with the Vatican,

spawned by the death of Stepinac in 1960 and the decisions of the Second Vatican Council,

was signed according new freedom to the Yugoslav Roman Catholic Church,

particularly to teach the catechism and open seminaries. The agreement

also eased tensions, which had prevented the naming of new bishops in

Yugoslavia since 1945. Tito's new socialism met opposition from

traditional communists culminating in conspiracy headed by Aleksandar Ranković. In

the same year Tito declared that Communists must henceforth chart

Yugoslavia's course by the force of their arguments (implying a

granting of freedom of discussion and an abandonment of dictatorship). The state security agency (UDBA) saw its power scaled back and its staff reduced to 5000. On

1 January 1967, Yugoslavia was the first communist country to open its

borders to all foreign visitors and abolish visa requirements. In

the same year Tito became active in promoting a peaceful resolution of

the Arab-Israeli conflict. His plan called for Arabs to recognize the State

of Israel in exchange for territories Israel gained. In 1967, Tito offered Czechoslovak leader Alexander Dubček to fly to Prague on three hours notice if Dubček needed help in facing down the Soviets. In

1971, Tito was re-elected as President of Yugoslavia for the sixth

time. In his speech in front of the Federal Assembly he introduced 20

sweeping constitutional amendments that would provide an updated

framework on which the country would be based. The amendments provided

for a collective presidency, a 22 member body consisting of elected

representatives from six republics and two autonomous provinces. The

body would have a single chairman of the presidency and chairmanship

would rotate among six republics. When the Federal Assembly fails to

agree on legislation, the collective presidency would have the power to

rule by decree. Amendments also provided for stronger cabinet with

considerable power to initiate and pursue legislature independently

from the Communist Party. Džemal Bijedić was

chosen as the Premier. The new amendments aimed to decentralize the

country by granting greater autonomy to republics and provinces. The

federal government would retain authority only over foreign affairs,

defense, internal security, monetary affairs, free trade within

Yugoslavia, and development loans to poorer regions. Control of

education, healthcare, and housing would be exercised entirely by the

governments of the republics and the autonomous provinces. Tito's

greatest strength, in the eyes of the western communists, had been in

suppressing nationalist insurrections and maintaining unity throughout

the country. It was Tito's call for unity, and related methods, that

held together the people of Yugoslavia. This ability was put to a test

several times during his reign, notably during the so-called Croatian Spring (also referred to as masovni pokret, maspok, meaning "mass movement") when the government had to suppress both

public demonstrations and dissenting opinions within the Communist

Party. During the Spring, on 22 December 1971 in Rudo Broz allegedly said, "The Sava will flow upstream before the Croats get their own state". Despite this suppression, much of maspok's demands were later realised with the new constitution. On 16 May 1974, the new Constitution was passed, and Josip Broz Tito was named President for life. Tito

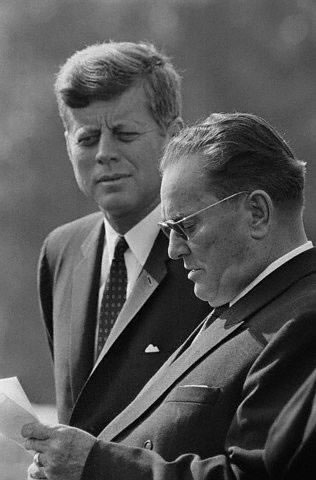

was notable for pursuing a foreign policy of neutrality during the Cold

War and for establishing close ties with developing countries. Tito's

strong belief in self-determination caused early rift with Stalin and

consequently, the Eastern Bloc.

His public speeches often reiterated that policy of neutrality and

cooperation with all countries would be natural as long as these

countries did not use their influence to pressure Yugoslavia to take

sides. Relations with the United States and Western European nations

were generally cordial. Yugoslavia

had a liberal travel policy permitting foreigners to freely travel

through the country and its citizens to travel worldwide. This was limited by most Communist countries. A number of Yugoslav citizens worked throughout Western Europe. After

the constitutional changes of 1974, Tito increasingly took the role of

senior statesman. His direct involvement in domestic policy and

governing was somewhat diminishing. On 7 January and again on 11 January 1980, Tito was admitted to the Medical Centre Ljubljana (in Ljubljana, SR Slovenia) with circulation problems in his legs. His left leg was amputated soon afterward due to a constricted artery. He died there from gangrene on 4 May 1980 at 3:05 pm. His funeral drew many world statesmen. Based on the number of attending politicians and state delegations, at the time it was the largest state funeral in history. They

included four kings, thirty-one presidents, six princes, twenty-two

prime ministers and forty-seven ministers of foreign affairs. They came

from both sides of the Cold War, from 128 different countries. At

the time of his death, speculation began about whether his successors

could continue to hold Yugoslavia together. Ethnic divisions and

conflict grew and eventually erupted in a series of Yugoslav wars a decade after his death. Tito was buried in a mausoleum in Belgrade, called Kuća Cveća (The House of Flowers) and numerous people visit the place as a shrine to "better times". The

gifts he received during his presidency are kept in the Museum of the

History of Yugoslavia (whose old names were "Museum 25 May," and

"Museum of the Revolution") in Belgrade. The collection includes works

of many world-notable artists, including original prints of Los Caprichos by Francisco Goya, and many others. The Government of Serbia has planned to merge the museum into the Museum of the History of Serbia. A popular explanation of the sobriquet claims that it is a conjunction of two Serbo-Croatian words, "ti" (meaning "you") and "to"

(meaning "that"). As the story goes, during the frantic times of his

command, he would issue commands with those two words, by pointing to

the person, and then the task. Tito is also an old, though uncommon, Croatian name, corresponding to Titus. Tito's biographer, Vladimir Dedijer, claimed that it came from the Croatian romantic writer, Tituš Brezovački,

but the name is very well known in Zagorje. Josip Broz in a hand

written note from 1958 (the note is kept in Archive of Communist Party

of Yugoslavia) confirmed that this name was very common in his region,

and it was the main reason for adopting it between 1934 and 1936.

Previously he used names Rudi (for domestic activities ) and Walter

(for international activities). However, Rodoljub Čolaković already used name Rudi too, so Josip Broz replaced it with Tito. Tito himself confirmed that he used the nickname "Walter", possibly after the German Walther PPK pistol. The

newest theory is from the Croatian journalist Denis Kuljiš. He got

information from a descendant of the Comintern spy Baturin, operating

in Istanbul in the thirties, about a code system that was used by the

latter. Josip Broz was one of his agents, and his secret nicknames were

allegedly always the names of pistols. According to Baturin, one of the

last nicknames was "TT", after the Soviet TT-30 pistol,

and Broz even signed a number of Communist Party documents with that

name after returning to Yugoslavia. Kuljiš believes that after a few

years "TT" (pronounced in Serbo-Croatian as "te te") became "Tito".

Tito also developed warm relations with Burma under U Nu, traveling to the country in 1955 and again in 1959, though he didn't receive the same treatment in 1959 from the new leader, Ne Win. Because

of its neutrality, Yugoslavia would often be rare among Communist

countries to have diplomatic relations with right-wing, anti-Communist governments. For example, Yugoslavia was the only communist country allowed to have an embassy in Alfredo Stroessner's Paraguay. However, one notable exception to Yugoslavia's neutral stance toward anti-communist countries was Chile under Augusto Pinochet; Yugoslavia was one of many left-wing countries which severed diplomatic relations with Chile after Allende was overthrown.