<Back to Index>

- Archaeologist Howard Carter, 1874

- Poet Dante Alighieri, 1265

- Leader of the Indian National Congress Gopal Krishna Gokhale, 1866

Dante Alighieri (May/June c.1265 – September 14, 1321), commonly known as Dante, was an Italian poet of the Middle Ages. The name Dante is, according to the words of Jacopo Alighieri, a hypocorism for Durante. In contemporary documents it is followed by the patronymic Alagherii or de Alagheriis; it was Boccaccio who popularized the form Alighieri.

His Divine Comedy, originally called Commedia by the author and later nicknamed Divina by Boccaccio, is often considered the greatest literary work composed in the Italian language and a masterpiece of world literature. In Italy he is known as "the Supreme Poet" (il Sommo Poeta) or just il Poeta. Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio are also known as "the three fountains" or "the three crowns". Dante is also called the "Father of the Italian language". The first biography written on him was by Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375), who wrote the Trattatello in laude di Dante.

The

exact date of Dante's birth is not known, although it is generally

believed to be around 1265. Dante claimed that his family descended from the ancient Romans (Inferno, XV, 76), but the earliest relative he could mention by name was Cacciaguida degli Elisei (Paradiso, XV, 135), of no earlier than about 1100. Dante's father, Alighiero di Bellincione, was a White Guelph who suffered no reprisals after the Ghibellines won the Battle of Montaperti in the mid 13th century. This suggests that Alighiero or his family enjoyed some protective prestige and status. Dante's family was prominent in Florence, with loyalties to the Guelphs, a political alliance that supported the Papacy and which was involved in complex opposition to the Ghibellines, who were backed by the Holy Roman Emperor.

The poet's mother was Bella degli Abati. She died when Dante was not

yet ten years old, and Alighiero soon married again, to Lapa di

Chiarissimo Cialuffi. It is uncertain whether he really married her, as

widowers had social limitations in these matters. This woman definitely

bore two children, Dante's brother Francesco and sister Tana (Gaetana).

When Dante was 12, he was promised in marriage to Gemma di Manetto

Donati, daughter of Messer Manetto Donati. Contracting marriages at

this early age was quite common and involved a formal ceremony,

including contracts signed before a notary. Dante had already fallen in love with another woman, Beatrice Portinari (known

also as Bice). Years after his marriage to Gemma, he met Beatrice

again. He had become interested in writing verse, and although he wrote

several sonnets to Beatrice, he never mentioned his wife Gemma in any

of his poems. Dante fought in the front rank of the Guelph cavalry at the battle of Campaldino (June 11, 1289). This victory brought forth a reformation of the Florentine constitution.

To take any part in public life, one had to be enrolled in one of "the

arts". So Dante entered the guild of physicians and apothecaries. In

following years, his name is frequently found recorded as speaking or

voting in the various councils of the republic. Dante

had several children with Gemma. As often happens with significant

figures, many people subsequently claimed to be Dante's offspring;

however, it is likely that Jacopo, Pietro, Giovanni and Antonia were

truly his children. Antonia became a nun with the name of Sister

Beatrice. Not much is known about Dante's education, and it is presumed he studied at home. It is known that he studied Tuscan poetry, at a time when the Sicilian School (Scuola poetica siciliana), a cultural group from Sicily, was becoming known in Tuscany. His interests brought him to discover the Occitan poetry of the troubadours and the Latin poetry of classical antiquity (with a particular devotion to Virgil). During the "Secoli Bui" (Dark Ages), Italy had become a mosaic of small states, Sicily being the largest one, at the time under Angevin rule, and as far (culturally and politically) from Tuscany as Occitania was:

the regions did not share a language, culture or easy communications.

Nevertheless, we can assume that Dante was a keen up-to-date

intellectual with international interests. When he was nine years old he met Beatrice Portinari,

daughter of Folco Portinari, with whom he fell in love "at first

sight", and apparently without even having spoken to her. He saw her

frequently after age 18, often exchanging greetings in the street, but

he never knew her well; he effectively set the example for the

so-called "courtly love".

It is hard now to understand what this love actually consisted of, but

something extremely important was happening within Italian culture. It

was in the name of this love that Dante gave his imprint to the "Dolce Stil Novo" (Sweet New Style) and would lead poets and writers to discover the themes of Love (Amore), which had never been so emphasized before. Love for Beatrice (as in a different manner Petrarch would

show for his Laura) would apparently be the reason for poetry and for

living, together with political passions. In many of his poems, she is

depicted as semi-divine, watching over him constantly. When Beatrice

died in 1290, Dante tried to find a refuge in Latin literature. The Convivio reveals that he had read Boethius's De consolatione philosophiae and Cicero's De amicitia. He then dedicated himself to philosophical studies at religious schools like the Dominican one in Santa Maria Novella. He took part in the disputes that the two principal mendicant orders (Franciscan and Dominican) publicly or indirectly held in Florence, the former explaining the doctrine of the mystics and of Saint Bonaventure, the latter presenting Saint Thomas Aquinas' theories. At 18, Dante met Guido Cavalcanti, Lapo Gianni, Cino da Pistoia and soon after Brunetto Latini; together they became the leaders of the Dolce Stil Novo. Brunetto later received a special mention in the Divine Comedy (Inferno, XV, 28), for what he had taught Dante. Nor speaking less on that account, I go With Ser Brunetto, and I ask who are His most known and most eminent companions. Some fifty poetical components by Dante are known (the so-called Rime, rhymes), others being included in the later Vita Nuova and Convivio. Other studies are reported, or deduced from Vita Nuova or the Comedy, regarding painting and music.

Dante, like most Florentines of his day, was embroiled in the Guelph-Ghibelline conflict. He fought in the battle of Campaldino (June 11, 1289), with the Florentine Guelphs against Arezzo Ghibellines, then in 1294 he was among the escorts of Charles Martel of Anjou (grandson

of Charles I of Naples more commonly called Charles of Anjou) while he

was in Florence. To further his political career, he became a

pharmacist. He did not intend to actually practice as one, but a law

issued in 1295 required that nobles who wanted public office had to be

enrolled in one of the Corporazioni delle Arti e dei Mestieri,

so Dante obtained admission to the apothecaries' guild. This profession

was not entirely inapt, since at that time books were sold from

apothecaries' shops. As a politician, he accomplished little, but he

held various offices over a number of years in a city undergoing

political unrest. After defeating the Ghibellines, the Guelphs divided into two factions: the White Guelphs (Guelfi Bianchi) -- Dante's party, led by Vieri dei Cerchi -- and the Black Guelphs (Guelfi Neri), led by Corso Donati.

Although initially the split was along family lines, ideological

differences rose based on opposing views of the papal role in

Florentine affairs, with the Blacks supporting the Pope and the Whites

wanting more freedom from Rome. Initially the Whites were in power and

expelled the Blacks. In response, Pope Boniface VIII planned a military occupation of Florence. In 1301, Charles de Valois, brother of Philip the Fair king of France, was expected to visit Florence because the Pope had appointed him peacemaker for Tuscany.

But the city's government had treated the Pope's ambassadors badly a

few weeks before, seeking independence from papal influence. It was

believed that Charles de Valois would eventually have received other

unofficial instructions. So the council sent a delegation to Rome to ascertain the Pope's intentions. Dante was one of the delegates. Boniface quickly dismissed the other delegates and asked Dante alone to remain in Rome. At the same time (November 1, 1301), Charles de Valois entered

Florence with Black Guelphs, who in the next six days destroyed much of

the city and killed many of their enemies. A new Black Guelph

government was installed and Messer Cante de' Gabrielli da Gubbio was appointed Podestà of

Florence. Dante was condemned to exile for two years, and ordered to

pay a large fine. The poet was still in Rome, where the Pope had

"suggested" he stay, and was therefore considered an absconder. He did

not pay the fine, in part because he believed he was not guilty, and in

part because all his assets in Florence had been seized by the Black

Guelphs. He was condemned to perpetual exile, and if he returned to

Florence without paying the fine, he could be burned at the stake. (The

city council of Florence finally passed a motion rescinding Dante's

sentence in June 2008.) He

took part in several attempts by the White Guelphs to regain power, but

these failed due to treachery. Dante, bitter at the treatment he

received from his enemies, also grew disgusted with the infighting and

ineffectiveness of his erstwhile allies, and vowed to become a party of

one. At this point, he began sketching the foundation for the Divine Comedy, a work in 100 cantos, divided into three books of thirty-three cantos each, with a single introductory canto. Dante went to Verona as a guest of Bartolomeo I della Scala, then moved to Sarzana in Liguria. Later, he is supposed to have lived in Lucca with Madame Gentucca, who made his stay comfortable (and was later gratefully mentioned in Purgatorio, XXIV, 37). Some speculative sources say that he was also in Paris between 1308 and 1310. Other sources, even less trustworthy, take him to Oxford. In 1310, the Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII of Luxembourg, marched 5,000 troops into Italy. Dante saw in him a new Charlemagne who

would restore the office of the Holy Roman Emperor to its former glory

and also re-take Florence from the Black Guelphs. He wrote to Henry and

several Italian princes, demanding that they destroy the Black Guelphs.

Mixing religion and private concerns, he invoked the worst anger of God

against his city, suggesting several particular targets that coincided

with his personal enemies. It was during this time that he wrote De Monarchia, proposing a universal monarchy under Henry VII, and the first two books of the Divine Comedy. In Florence, Baldo d'Aguglione pardoned

most of the White Guelphs in exile and allowed them to return; however,

Dante had gone too far in his violent letters to Arrigo (Henry VII), and he was not recalled. In

1312, Henry assaulted Florence and defeated the Black Guelphs, but

there is no evidence that Dante was involved. Some say he refused to

participate in the assault on his city by a foreigner; others suggest

that he had become unpopular with the White Guelphs too and that any

trace of his passage had carefully been removed. In 1313, Henry VII

died, and with him any hope for Dante to see Florence again. He

returned to Verona, where Cangrande I della Scala allowed

him to live in a certain security and, presumably, in a fair amount of

prosperity. Cangrande was admitted to Dante's Paradise (Paradiso, XVII, 76). In 1315, Florence was forced by Uguccione della Faggiuola (the

military officer controlling the town) to grant an amnesty to people in

exile, including Dante. But Florence required that as well as paying a

sum of money, these exiles would do public penance.

Dante refused, preferring to remain in exile. When Uguccione defeated

Florence, Dante's death sentence was commuted to house arrest, on

condition that he go to Florence to swear that he would never enter the

town again. Dante refused to go. His death sentence was confirmed and

extended to his sons. Dante still hoped late in life that he might be

invited back to Florence on honorable terms. For Dante, exile was

nearly a form of death, stripping him of much of his identity. He

addresses the pain of exile in Paradiso, XVII (55-60), where Cacciaguida, his great-great-grandfather, warns him what to expect.

Prince Guido Novello da Polenta invited him to Ravenna in 1318, and he accepted. He finished the Paradiso, and died in 1321 (at the age of 56) while returning to Ravenna from a diplomatic mission to Venice, possibly of malaria contracted there. Dante was buried in Ravenna at the Church of San Pier Maggiore (later called San Francesco). Bernardo Bembo, praetor of Venice in 1483, took care of his remains by building a better tomb. Eventually,

Florence came to regret Dante's exile, and made repeated requests for

the return of his remains. The custodians of the body at Ravenna

refused to comply, at one point going so far as to conceal the bones in

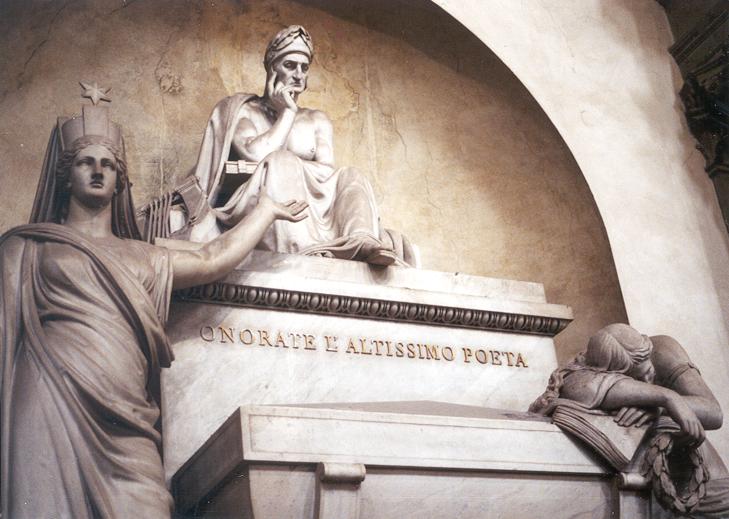

a false wall of the monastery. Nevertheless, in 1829, a tomb was built

for him in Florence in the basilica of Santa Croce. That tomb has been empty ever

since, with Dante's body remaining in Ravenna, far from the land he

loved so dearly. The front of his tomb in Florence reads Onorate l'altissimo poeta - which roughly translates as "Honour the most exalted poet". The phrase is a quote from the fourth canto of the Inferno,

depicting Virgil's welcome as he returns among the great ancient poets

spending eternity in Limbo. The continuation of the line, L'ombra sua torna, ch'era dipartita ("his spirit, which had left us, returns"), is poignantly absent from the empty tomb. In

2007, a reconstruction of Dante's face was completed in a collaborative

project. Artists from Pisa University and engineers at the University

of Bologna at Forli completed the revealing model, which indicated that

Dante's features were somewhat different than was once thought.