<Back to Index>

- Surgeon and Anatomist Edward Anthony Jenner, 1749

- Painter Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi (Sandro Botticelli), 1445

- King of Spain Alfonso XIII, 1886

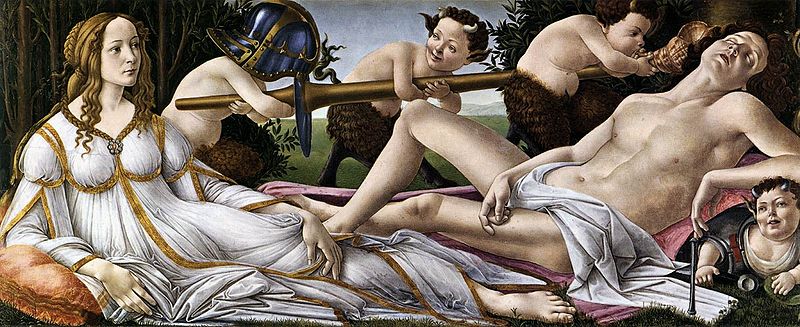

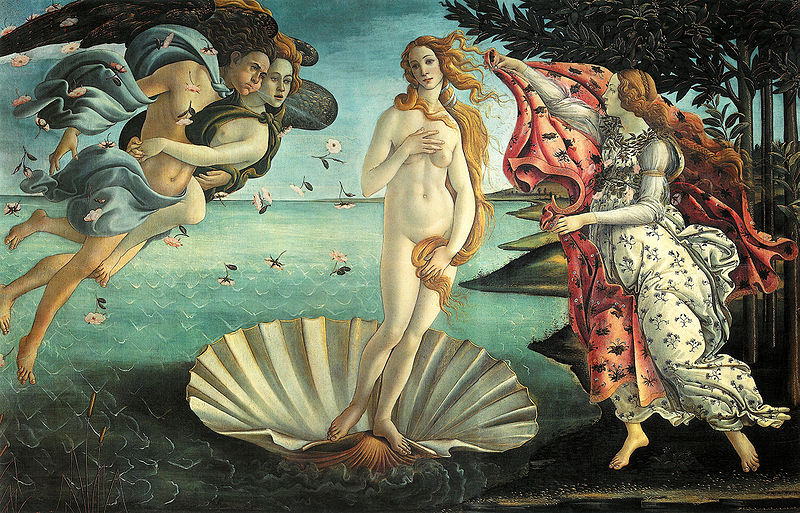

Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi, better known as Sandro Botticelli or Il Botticello ("The Little Barrel"; c. 1445 – May 17, 1510) was an Italian painter of the Florentine school during the Early Renaissance (Quattrocento). Less than a hundred years later, this movement, under the patronage of Lorenzo de' Medici, was characterized by Giorgio Vasari as a "golden age", a thought, suitably enough, he expressed at the head of his Vita of Botticelli. His posthumous reputation suffered until the late 19th century; since then his work has been seen to represent the linear grace of Early Renaissance painting, and The Birth of Venus and Primavera rank now among the most familiar masterpieces of Florentine art.

Details of Botticelli's life are sparse, but we know that he became an apprentice when he was about fourteen years old, which would indicate that he received a fuller education than did other Renaissance artists. He was born in the city of Florence. Vasari reported that he was initially trained as a goldsmith by his brother Antonio. Probably by 1462 he was apprenticed to Fra Filippo Lippi; many of his early works have been attributed to the elder master, and attributions continue to be uncertain. Influenced also by the monumentality of Masaccio's painting, it was from Lippi that Botticelli learned a more intimate and detailed manner. As recently discovered, during this time, Botticelli could have traveled to Hungary, participating in the creation of a fresco in Esztergom, ordered in the workshop of Fra Filippo Lippi by Vitéz János, then archbishop of Hungary.

By

1470 Botticelli had his own workshop. Even at this early date his work

was characterized by a conception of the figure as if seen in low

relief, drawn with clear contours, and minimizing strong contrasts of

light and shadow which would indicate fully modeled forms. The masterworks Primavera (c. 1482) and The Birth of Venus (c.

1485) were both seen by Vasari at the villa of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco

de' Medici at Castello in the mid-16th century, and until recently, it

was assumed that both works were painted specifically for the villa.

Recent scholarship suggests otherwise: the Primavera was painted for Lorenzo's townhouse in Florence, and The Birth of Venus was commissioned by someone else for a different site. By 1499, both had been installed at Castello. In these works, the influence of Gothic realism

is tempered by Botticelli's study of the antique. The complex meanings of these paintings continue to

receive widespread scholarly attention, mainly focusing on the poetry

and philosophy of humanists who were the artist's contemporaries. The Adoration of the Magi for Santa Maria Novella (c. 1475-1476, now at the Uffizi) contains the portraits of Cosimo de' Medici, his grandson Giuliano de' Medici, and Cosimo's son Giovanni. The quality of the scene was hailed by Vasari as one of Botticelli's pinnacles. In 1481, Pope Sixtus IV summoned Botticelli and other prominent Florentine and Umbrian artists to fresco the walls of the Sistine Chapel. The iconological program was the supremacy of the Papacy. Sandro's

contribution was moderately successful. He returned to Florence, and

"being of a sophistical turn of mind, he there wrote a commentary on a

portion of Dante and illustrated the Inferno which

he printed, spending much time over it, and this abstention from work

led to serious disorders in his living." Thus Vasari characterized the

first printed Dante (1481) with Botticelli's decorations; he could not imagine that the new art of printing might occupy an artist. In the mid-1480s Botticelli worked on a major fresco cycle with Perugino, Ghirlandaio, and Filippino Lippi, for Lorenzo the Magnificent's villa near Volterra; in addition he painted many frescoes in Florentine churches. In 1491 Botticelli served on a committee to decide upon a facade for the Florence Duomo.

In 1502 he was accused of sodomy, though charges were later dropped. In

1504 he was a member of the committee appointed to decide where Michelangelo's David would be placed. His later work, especially as seen in a series on the life of St. Zenobius,

witnessed a diminution of scale, expressively distorted figures, and a

non-naturalistic use of colour reminiscent of the work of Fra Angelico nearly a century earlier. In later life, Botticelli was one of Savonarola's followers, though the full extent of Savonarola's influence is uncertain. The story that he burnt his own paintings on pagan themes in the notorious "Bonfire of the Vanities"

is not told by Vasari, who nevertheless asserts that of the sect of

Savonarola "he was so ardent a partisan that he was thereby induced to

desert his painting, and, having no income to live on, fell into very

great distress. For this reason, persisting in his attachement to that

party, and becoming a Piagnone he

abandoned his work.". Botticelli biographer Ernst Steinman searched for

the artist's psychological development through his Madonnas. In the

"deepening of insight and expression in the rendering of Mary's

physiognomy", Steinman discerns proof of Savonarola's influence over

Botticelli. This means that the biographer needed to alter the dates of

a number of Madonnas to substantiate his theory; specifically, they are

dated ten years later than before. Steinman disagrees with Vasari's

assertion that Botticelli produced nothing after coming under the

influence of Girolamo Savonarola. Steinman believes the spiritual and

emotional Virgins rendered by Sandro follow directly from the teachings

of the Dominican monk. Earlier, Botticelli had painted an Assumption of the Virgin for

Matteo Palmieri in a chapel at San Pietro Maggiore in which, it was

rumored, both the patron who dictated the iconic scheme and the painter

who painted it, were guilty of unidentified heresy, a delicate requirement in such a subject. This is a common misconception based on an error by Vasari. The painting referred to, now in the National Gallery in London, is by the artist Botticini. Vasari confused their similar sounding names.

Botticelli never wed, and expressed a strong aversion to the idea of marriage, a prospect he claimed gave him nightmares. The popular view is that he suffered from unrequited love for Simonetta Vespucci, a married noblewoman. According to legend, she had served as the model for The Birth of Venus and

recurs throughout his paintings, despite the fact that she had died

years earlier, in 1476. Botticelli asked that when he die he be buried

at her feet in the Church of Ognissanti in Florence. His wish was carried out when he died some 34 years later, in 1510. Some modern historians have also examined other aspects of his sexuality. In 1938, Jacques Mesnil discovered

a summary of a charge in the Florentine Archives for November 16, 1502,

which read simply, "Botticelli keeps a boy". The painter would then

have been fifty-eight. Mesnil dismissed it as a customary slander by

which partisans and adversaries of Savonarola abused each other. Opinion remains divided on whether this is evidence of homosexuality. Many have firmly backed Mesnil, but others have cautioned against hasty dismissal of the charge.

Yet while speculating on the subject of his paintings, Mesnil

nevertheless concluded "woman was not the only object of his love".

Botticelli

was already little employed in 1502; after his death his reputation was

eclipsed longer and more thoroughly than that of any other major

European artist. His paintings remained in the churches and villas for which they had been created, his frescoes in the Sistine Chapel upstaged by Michelangelo's. British collector and art historian William Young Ottley however had brought Botticelli's The Mystical Nativity to

London with him in 1799 after buying it in Italy. After Ottley's death

its next purchaser allowed it to be exhibited in a major art exhibition

held in Manchester in 1857, The Art Treasures Exhibition,

where amongst many other art works it was viewed by more than a million

people. The first nineteenth century art historian to have looked with

satisfaction at Botticelli's Sistine frescoes was Alexis-François Rio. Through Rio, Anna Brownell Jameson and Charles Eastlake were alerted to Botticelli, but, while works by his hand began to appear in German collections, both the Nazarene movement and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood ignored him. Walter Pater created a literary picture of Botticelli, who was then taken up by the

Aesthetic movement. The first monograph on the artist was published in

1893; then, between 1900 and 1920 more books were written on Botticelli

than any other painter.