<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte, 1762

- Composer Johann Jakob Froberger, 1616

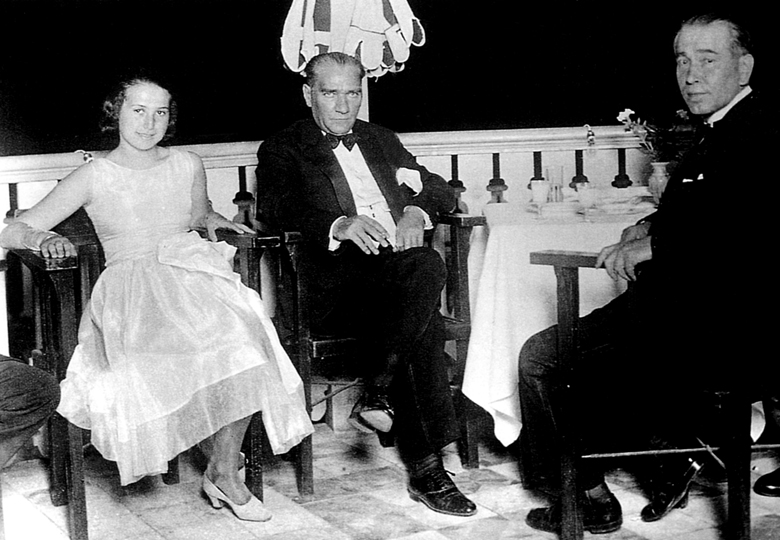

- President of Turkey Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, 1881

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (indeterminate, 1881–10 November 1938) was a Turkish army officer, revolutionary statesman, and founder of the Republic of Turkey as well as its first President. Also the spiritual leader of Turkish people, according to the value of his efforts and revolutions.

Atatürk became known as an extremely capable military officer by being the only undefeated Ottoman commander during World War I. Following the defeat of the Ottoman Empire, he led the Turkish national movement in the Turkish War of Independence. Having established a provisional government in Ankara, he defeated the forces sent by the Allies. His successful military campaigns led to the liberation of the country and to the establishment of Turkey. During his presidency, Atatürk embarked upon a program of political, economic, and cultural reforms. An admirer of the Age of Enlightenment, he sought to transform the former Ottoman Empire into a modern, democratic, and secular nation-state. The principles of Atatürk's reforms, upon which modern Turkey was established, are referred to as Kemalism.

Born as Mustafa, his second name Kemal (meaning Perfection or Maturity) was given to him by his mathematics teacher in recognition of his academic excellence. Mustafa's father was Albanian, and his mother was Macedonian. Mustafa’s mother was Zubeyde Hanim (1857-1923), a devout Muslim and "as fair as any Slav from beyond the Bulgarian frontier" with "fine white" skin and "eyes of a deep but clear light blue". In his early years, his mother encouraged Mustafa to attend a religious school, something he did reluctantly and only briefly. Later, he attended Şemsi Efendi school (a private school with a more secular curriculum) at the direction of his father. His parents wanted him to have education in a trade, but without consulting them, Atatürk took an entrance exam for a military junior high school in Thessaloniki (in Turkish, Selanik, which was an Ottoman city at that time) in 1893. In 1896, he enrolled into a military high school in the Ottoman city of Manastır (modern Bitola, North Macedonia). In 1899, he enrolled at the War College in Istanbul and graduated in 1902. He later graduated from the War Academy on 11 January 1905.

Following graduation, he was assigned to Damascus as a lieutenant. He joined a small secret revolutionary society of reformist officers called Vatan ve Hürriyet ("Motherland and Liberty"). In 1907, he was promoted to the rank of captain and assigned to Manastır. He joined the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP,

'Young Turks'). However, in later years he became known for his

opposition to, and frequent criticism of, policies pursued by the CUP

leadership. In 1908, he played a role in theYoung Turk Revolution which seized power from Abdülhamid II. In 1910, he took part in the Picardie army maneuvers in France.

In 1911, he worked at the Ministry of War for a short time. Later in

1911, he was posted to the Ottoman province of Trablusgarp (present-day Libya) to fight in the Italo-Turkish War. He returned to the capital in October 1912 following the outbreak of the Balkan Wars. During the First Balkan War, he fought against the Bulgarian army at Gallipoli and Bolayır on the coast of Thrace. In 1913, he was appointed military attaché to Sofia and promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel in 1914. In 1914, the Ottoman Empire entered European and Middle Eastern theatres of World War I on the side of the Central Powers. Mustafa Kemal was given the task of organizing and commanding the 19th Division attached to the Fifth Army during the Battle of Gallipoli.

Mustafa Kemal became the outstanding front-line commander after

correctly anticipating where the Allies would attack and holding his

position until they retreated. Following the Battle of Gallipoli,

Mustafa Kemal served in Edirne until 14 January 1916. He was then assigned to the command of the XVI Corps of the Second Army and sent to the Caucasus Campaign.

The massive Russian offensive had reached the Anatolian key cities. On

7 August, Mustafa Kemal rallied his troops and mounted a

counteroffensive. Two of his divisions captured not only Bitlis but the equally important town of Muş, greatly upsetting the calculations of the Russian Command. On 7 March 1917, Mustafa Kemal was promoted from the command of the XVI Corps to the overall command of the 2nd Army. The Russian Revolution erupted and the Caucasus front of the Czar's armies disintegrated. Mustafa Kemal had already left the region and was assigned to the command of the 7th Army at the Sinai and Palestine Campaign. He returned to Aleppo on

28 August 1918, and resumed command. Mustafa Kemal retreated towards

Jordan to establish a stronger defensive line against the British

forces that won against the German commander Liman von Sanders' troops at the Battle of Megiddo, whom Mustafa Kemal served under as commander of the ill-fated Ottoman Seventh Army. Afterwards he was appointed to the command of Thunder Groups Command (Turkish: Yıldırım Orduları Gurubu), replacing Liman von Sanders. Mustafa Kemal's position became the base line for the Armistice of Mudros. Kemal's

last active service in the Ottoman Army was organizing the return of

the troops who were left behind south of his line. Mustafa Kemal

returned to an occupied Constantinople (present-day Istanbul), the Ottoman capital, on 13 November 1918. Along the established lines of partitioning of the Ottoman Empire, British, Italian, French and Greek forces began to occupy Anatolia. The occupation of Constantinople along with the occupation of İzmir mobilized the establishment of the Turkish national movement and the Turkish War of Independence. Mustafa

Kemal's active participation in the national resistance movement began

with his assignment as a General Inspector to oversee the

demobilization of remaining Ottoman military units and nationalist

organizations. On 19 May 1919, he reached Samsun. His first goal was the establishment of an organized national resistance movement against the occupying forces. In June 1919, he and his close friends declared that the independence of the country was

in danger. He resigned from the Ottoman Army on 8 July and the Ottoman

government issued a warrant for his arrest. Later, he was condemned to

death. Mustafa Kemal called for a national election to establish a new Turkish Parliament that would have its seat in Ankara. On

12 February 1920, the last Ottoman Parliament gathered in the capital.

This parliament was dissolved by British forces after it declared the Misak-ı Milli ("National Pact"). Mustafa Kemal used this opportunity to establish the "Grand National Assembly" (GNA). On 23 April 1920, the GNA opened with Mustafa Kemal as the speaker. On 10 August 1920, the Ottoman Grand Vizier Damat Ferid Pasha signed the Treaty of Sèvres. It finalized the plans for the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire,

including the regions that Turkish nationals viewed as their heartland.

Mustafa Kemal insisted on complete independence and the safeguarding of

the interests of the Turkish majority on Turkish soil. He persuaded the

GNA to gather a National Army. The Army faced the Allied occupation

forces and fought on three fronts: in the Franco-Turkish, the Greco-Turkish and the Turkish-Armenian wars. After a series of initial battles during the Greco-Turkish war, the Greek army advanced as far as the Sakarya River, just eighty kilometers west of the GNA. On 5 August 1921, Mustafa Kemal was promoted to Commander in chief of the forces by GNA. The ensuing Battle of Sakarya was

fought from 23 August to 13 September 1921 and ended with the defeat of

the Greeks. The Allies, ignoring the extent of Kemal's successes, hoped

to impose a modified version of the Treaty of Sèvres as

a peace settlement on Ankara, but the proposal was rejected. In August

1922, Kemal launched an all-out attack on the Greek lines at Afyon karahisar, the Battle of Dumlupınar and finally the Turkish forces regained control of Smyrna (modern day Izmir) on September 9, 1922. On September 10, 1922, Mustafa Kemal sent a telegram to the League of Nations saying

that on account of the excited spirit of the Turkish population, the

Ankara Government would not be responsible for massacres. The Conference of Lausanne began on 21 November 1922. Turkish representative İsmet İnönü refused any proposal that would compromise Turkish sovereignty, major matters regarding the control of Turkish finances, the Capitulations, the Turkish Straits, justice, and the like. On 24 July 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne was signed. The final outcome of the independence war came with the proclamation of the Republic of Turkey on 29 October 1923. With

the establishment of the Republic of Turkey, efforts to modernise the

country started. The institutions and constitutions of Western states

such as France, Sweden, Italy, and Switzerland were analyzed and

adapted according to the needs and characteristics of the Turkish

nation. Highlighting the public's lack of knowledge regarding Kemal's

intentions, the public cheered: "We are returning to the days of the first caliphs". In order to establish reforms, Mustafa Kemal placed Fevzi Çakmak, Kazım Özalp and İsmet İnönü in

important political positions. Mustafa Kemal capitalized on his

reputation as an efficient military leader and spent the following

years, up until his death in 1938, instituting wide-ranging and

progressive political, economic, and social reforms. In doing so, he

transformed Turkish society from perceiving itself as Muslim subjects

of a vast Empire into citizens of a modern, democratic, and secular

nation-state. He

led wide-ranging reforms in social, cultural, and economical aspects.

As a result, the new Republic's backbone of legislative, judicial, and

economic structures was put in place with these reforms. Mustafa

Kemal created a banner to mark the changes between the old Ottoman and

the new Republican rule. Each change was symbolized as an arrow in this

banner. The new citizens of the Republic, who had been subjects of the

Ottoman Empire only a few years ago, carried this banner to remind them

of the major concepts of this new establishment. This defining ideology

of the Republic of Turkey is referred to as the "Six Arrows" or Kemalist ideology. Kemalist ideology is based on Mustafa Kemal's conception of realism and pragmatism. The

fundamentals of nationalism, populism and etatism were all defined

under the Six Arrows. These fundamentals were not new in world politics

or, indeed, among the elites of Turkey. What made them unique was that

these interrelated fundamentals were formulated specifically for

Turkey's needs. A good example is the definition and application of

secularism; the Kemalist secular state significantly differed from

predominantly Christian states. Mustafa

Kemal's private journal entries dated before the establishment of the

republic in 1923 show that he believed in the importance of the

sovereignty of the people. In forging the new republic, the Turkish

revolutionaries turned their back on the perceived corruption and

decadence of cosmopolitan Istanbul and its Ottoman heritage. For instance, they made Ankara the

country's new capital. A provincial town deep in Anatolia, it was

turned into the center of the independence movement. Ataturk wanted a

"direct government by the Assembly" and visualized a representative democracy, parliamentary sovereignty, where the National Parliament would be the ultimate source of power. But,

in the following years, he took the position that the country needed an

immense amount of reconstruction, and that "direct government by the

Assembly" could not survive in such an environment. The revolutionaries

regularly faced challenges from the supporters of the old Ottoman

regime, and also from the supporters of relatively new ideologies such

as communism and fascism. Mustafa Kemal saw the consequences of fascist and communist doctrines in the 1920s and 1930s and rejected both. He prevented the spread of totalitarian party rule which held sway in the Soviet Union, Germany and Italy. Some

perceived his opposition and silencing of these ideologies as a means

of eliminating competition; others believed it was a necessary means to

protect the young Turkish state from succumbing to the instability of

new ideologies and competing factions. The heart of the new republic was the GNA. The GNA was established during the Turkish War of Independence by Mustafa Kemal. The elections were free and an egalitarian electoral system that was based on a general ballot was used. The

role of deputies at the GNA was to be the voice of Turkish society by

expressing its political views and preferences. It had the right to

select and control both the government and the Prime Minister.

Initially, it also acted as a legislative power, controlled the

executive and, if necessary, acted as an organ of scrutiny under the Turkish Constitution of 1921. But the Turkish Constitution of 1924 set a loose separation of powers between the legislative and the executive organs of the state, whereas the separation of these two within the judiciary system

was a strict one. Mustafa Kemal, then the President, occupied a

powerful position in this political system. The single-party regime was

established de facto in

1925 after the adoption of the 1924 constitution. The only political

party of the GNA was the "Peoples Party", founded by Mustafa Kemal in

the initial years of the independence war. On 9 September 1923 it was

renamed the Republican People's Party (Turkish Cumhuriyeti Halk Partisı). Abolition of the Caliphate was

an important dimension in Mustafa Kemal's drive to reform the political

system and to promote the national sovereignty. By the consensus of the

Muslim majority in the early centuries the caliphate was the core

political concept of Sunni Islam. Abolishing the sultanate was

easier because the survival of the Caliphate at the time satisfied the

partisans of the sultanate. This produced a two-headed system with the

new republic on one side and an Islamic form of government with the

Caliph on the other side. Kemal and İnönü worried that "it

nourished the expectations that the sovereign would return under the

guise of Caliph..." Caliph Abdülmecid II was

elected after the abolishment of the sultanate (1922). The

caliph had his own personal treasury and also had a personal service

that included military personnel; Mustafa Kemal said that there was no

"religious" or "political" justification for this. He believed that

Caliph Abdülmecid II was following in the steps of the sultans in

domestic and foreign affairs: accepting and responding to foreign

representatives and reserve officers, and participating in official

ceremonies and celebrations. He wanted to integrate the powers of the

caliphate into the powers of the GNA. His initial activities began on 1

January 1924. He

acquired the consent of İnönü, Çakmak and Özalp

before the abolition of the caliphate. The caliph made a statement to

the effect that he would not interfere with political affairs. On 3 March 1924, the caliphate was officially abolished and

its powers within Turkey were transferred to the GNA. The debate as to

the validity of Turkey's unilateral abolition of the caliphate was

taken up by other Muslim nations in order to decide whether they should

confirm the Turkish action or appoint a new caliph. A

"Caliphate Conference" was held in Cairo in May 1926 and a resolution

was passed declaring the caliphate "a necessity in Islam", but failed

to implement this decision. Two other Islamic conferences were held in Mecca (1926) and Jerusalem (1931), but failed to reach a consensus. Turkey

did not accept the re-establishment of the caliphate and perceived it

as an attack to its basic existence; while Mustafa Kemal and the

reformists continued their own way. The

removal of the caliphate followed with an extensive effort to establish

the separation of governmental and religious affairs. Education was the

cornerstone in this effort. In 1923 there were three main horizontal

educational institutions. The first and most common institution was medreses (local

school) based on Arabic, the Qur'an and memorization. The second type

of institution was idadî and sultanî which were the

reformist schools of the Tanzimat era.

The last group was the colleges and minority schools in foreign

languages that used the latest teaching models in educating pupils. The

old medrese education was modernized. Mustafa

Kemal changed the classical Islamic education with a vigorously

promoted reconstruction of educational institutions along the line of

an enlightened pragmatism. Kemal linked educational reform to the liberation of the nation from dogma,

which he believed was more important than the Turkish war of

independence. In the summer of 1924 Mustafa Kemal invited American

educational reformer John Dewey to Anakara to advise him for the reforms and recommendations. His public education reforms

aimed to prepare citizens for roles in public life through increasing

the public literacy. He wanted to institute compulsory primary education for

both girls and boys; since then this effort has been an ongoing task

for the republic. He pointed out that one of the main targets of education in Turkey had to be raising a generation nourished with what he called the "public culture". The state schools established a common curriculum which became known as the "unification of education." Unification

of education was put into force on 3 March 1924 by the Law on

Unification of Education (No. 430). With the new law, education became

inclusive, organized and operated on a deliberate model of the civil

community. It established a contemporary route to the traditional

social structure by causing contemporary citizen consciousness. In this

new design all schools submitted their curriculum to the "Ministry of National Education".

It was a government agency modeled after other ministries of education

of its time. Concurrently, the republic abolished the two ministries

and subordinated the clergy to the department of religious affairs. The change was one of the foundations of secularism in Turkey.

The unification of education under one curriculum was the end of

"clerics or clergy of the Ottoman Empire". It was not the end of

religious schools in Turkey which were moved to higher education until

consequent governments pulled them back to secondary education after Mustafa Kemal's death. Beginning in the fall of 1925 Mustafa Kemal encouraged the Turks to wear modern European attire. He

was determined to force the abandonment of the sartorial traditions of

the Middle East and finalize a series of dress reforms, which were

originally started by Mahmud II. The fez was established by Sultan Mahmud II in 1826 as part of the Ottoman Empire's modernization effort. The Hat Law of 1925 introduced the use of Western-style hats instead of the fez. Mustafa Kemal first made the hat compulsory to civil servants. The guidelines for the proper dressing of students and state employees

(anyone in public space controlled by the state) were passed during his

lifetime; many civil servants adopted the hat willingly. In 1925

Mustafa Kemal wore his "Panama hat" during a public appearance in Kastamonu,

one of the most conservative towns in Anatolia, to explain that the hat

was the headgear of civilized nations. The last part of reform on dress

emphasized the need to wear modern Western suits and Derby-style hats

instead of antiquated religion-based clothing such as the veil and

turban in the Law Relating to Prohibited Garments of 1934. Even

though he personally promoted modern dress for women, Mustafa Kemal

never made specific reference to women’s clothing in the law. In the

social conditions of the period, he believed that women would adapt to

the new way at their own will. He was frequently photographed on public

business with his wife Lâtife Uşaklıgil,

who covered her head in accordance with Islamic tradition. He was also

frequently photographed on public business with women wearing modern

Western clothes. But it was Atatürk's adopted daughters like Sabiha Gökçen and Afet İnan who

provided the real role model for the Turkish women of the future. On 30 August 1925, Mustafa Kemal's view on religious insignia used outside places of worship was introduced in his Kastamonu speech. On September 2 the government issued a decree closing down all Sufi orders and the tekkes. Mustafa Kemal ordered their dervish lodges to be converted to museums, such as Mevlana Museum in

Konya. The institutional expression of Sufism became illegal in Turkey;

a politically neutral form of Sufism, functioning as social

associations, was permitted to exist. The

abolition of the caliphate and other cultural reforms were met with

fierce opposition. The conservative elements were not happy and they

launched attacks on the Kemalist reformists. In 1924, while the "Issue of Mosul" was on the table, Sheikh Said Piran began to organize the Sheikh Said Rebellion. Sheikh Said Piran was a wealthy Kurdish hereditary chieftain (Tribal chief) of a local Naqshbandi order.

Piran emphasized the issue of religion; he not only opposed the

abolition of the Caliphate, but also the adoption of civil codes based

on Western models, the closure of religious orders, the ban on

polygamy, and the new obligatory civil marriage. Piran stirred up his

followers against the policies of the government, which he considered

to be against Islam. In an effort to restore Islamic law, Piran's

forces moved through the countryside, seized government offices and

marched on the important cities of Elazığ and Diyarbakır. Members

of the government saw the Sheikh Said Rebellion as an attempt at a

counter-revolution. They urged immediate military action to prevent its

spread. The "Law for the Maintenance of Public Order" was passed to

deal with the rebellion on 4 March 1925. It gave the government

exceptional powers and included the authority to shut down subversive

groups (The law was eventually repealed on 4 March 1929). There

were also parliamentarians in the GNA who were not happy with these

changes. There were so many members who were denounced as opposition

sympathizers at a private meeting of the Republican People's Party (CHP) that Mustafa Kemal expressed his fear of being among the minority in his own party. He decided not to purge this group. After a censure motion gave the chance to have a breakaway group, Kazım Karabekir,

along with his friends, established such a group on 17 October 1924.

The censure became a confidence vote at the CHP for Mustafa Kemal. On 8

November the motion was rejected by 148 votes to 18, and 41 votes were

absent. CHP held all but one seat in the parliament. After the majority of the CHP chose him Mustafa

Kemal said, "the Turkish nation is firmly determined to advance

fearlessly on the path of the republic, civilization and progress". On 17 November 1924, the breakaway group officially established the Progressive Republican Party (PRP) with 29 deputies and the first multi-party system began. The PRP's economic program suggested liberalism, in contrast to the state socialism of CHP, and its social program was based on conservatism in contrast to the modernism of

CHP. Leaders of the party strongly supported the Kemalist revolution in

principle, but had different opinions on the cultural revolution and

the principle of secularism. The

RPR was not against Mustafa Kemal's main positions as declared in its

program. The program supported the main mechanisms for establishing

secularism in the country and the civic law, or as stated, "the needs

of the age" (article 3) and the uniform system of education (article

49). These principles were set by the leaders at the onset. The only legal opposition became a home for all kinds of differing views. During 1926, a plot to assassinate Mustafa Kemal was uncovered in İzmir.

It originated with a former deputy who had opposed the abolition of the

Caliphate and had a personal grudge. The trail turned from an inquiry

of the planners of this attempt to an investigation carried out

ostensibly to uncover subversive activities and actually used to

undermine those with differing views regarding Kemal's cultural

revolution. The sweeping investigation brought before the tribunal a

large number of political opponents, including Karabekir, the leader of

PRP. A number of surviving leaders of the Committee of Union and Progress, who were at best second-rank in the Turkish movement, including Cavid, Ahmed Şükrü, and Ismail Canbulat were found guilty of treason and hanged. During

these investigations there was a link that was uncovered among the

members of the PRP to the Sheikh Said Rebellion. The PRP was dissolved

following the outcomes of the trial. The pattern of organized

opposition, however, was broken. This action was the only broad

political purge during Atatürk's presidency. Mustafa Kemal's

saying, "My mortal body will turn into dust, but the Republic of Turkey

will last forever," was regarded as a will after the assassination

attempt. In

the years following 1926, Mustafa Kemal introduced a radical departure

from previous reformations established by the Ottoman Empire. For

the first time in history, Islamic law was clearly separated from the

secular law of the nation and confined to its religious domain. On March 1, 1926 the Turkish penal code was passed. It was modeled after the Italian Penal Code. On October 4, 1926, Islamic courts were closed. Establishing the civic law needed time, so Kemal delayed the inclusion of the principle of laïcité until February 5, 1937. Ottoman practice discouraged the social interaction between men and women aligned with the Islamic practice of sex segregation.

Mustafa Kemal began to develop the concepts of his social reforms very

early, as was evident in his personal journal. He and his staff

constantly discussed issues like abolishing the veiling of women and

the integration of women to social life. Mustafa

Kemal needed a new civil code to establish his second major step of

giving freedom to women. The first part was the education of girls and

was established with the unification of education. On October 4, 1926,

the new Turkish civil code passed. It was modeled after the Swiss Civil Code.

Under the new code, women gained equality with men in such matters as

inheritance and divorce. Mustafa Kemal did not consider gender a factor

in social organization. According to his view, society marched towards

its goal with all its women and men together. He believed that it was

scientifically impossible for him to achieve progress and to become

civilized if the gender separation continued as in Ottoman times. In 1927, advocated by Mustafa Kemal, the State Art and Sculpture Museum (Turkish: Ankara Resim ve Heykel Müzesi)

opened its doors. The museum highlighted the art of sculpture, which

had hardly been practiced in Turkey owing to the Islamic tradition of

avoiding idolatry. Kemal believed that "culture is the foundation of

the Turkish Republic." and

described modern Turkey's ideological thrust as "a creation of

patriotism blended with a lofty humanist ideal." He included both his

own nation's creative legacy and what he saw as the admirable values of

global civilization. The pre-Islamic culture of the Turks became the subject of extensive research, and particular emphasis was laid upon the fact that, long before the Seljuk and Ottoman civilizations, the Turks have had a rich culture. He instigated the policy of studying the Anatolian civilizations such as the Phrygians and Lydians, foremost of which being the Sumerians and Hittites. To link the cultural signatures of the past into public attention, he personally named the "Sümerbank" (1932) after the Sumerians, and the "Etibank" (1935) after the Hittites. He also stressed the folk arts of the countryside as a wellspring of Turkish creativity. On November 1, 1928, Mustafa Kemal introduced the Turkish alphabet as a replacement for Arabic script and

as a solution to the literacy problem. Literate citizens of the country

comprised as little as 10% of the population at the time. Dewey noted

that learning how to read and write in Turkish with Arabic script took

roughly three years with rather strenuous methods at the elementary

level. They used the Ottoman Language written in Arabic script with Arabic and Persian loan vocabulary. The creation of the new Turkish alphabet as a variant of the Latin alphabet was undertaken by the Language Commission (Turkish: Dil Encümeni) with the initiative of Mustafa Kemal. The tutelage was received from an Ottoman-Armenian calligrapher. The first Turkish newspaper using

the new alphabet was published on December 15, 1928. Kemal himself

actively encouraged people and made many trips to the countryside in

order to teach the new alphabet. The adaptation to the new alphabet was

very quick. Beginning in 1932, the People's Houses (Turkish: Halk Evleri)

opened throughout the country. The older population of Turkey received

help at People's Houses. There were congresses for discussing the

issues of copyright, public education and scientific publishing.

Literacy reform was also supported by strengthening the private

publishing sector with a new law on copyrights. Mustafa Kemal promoted modern teaching methods at the primary education level, and Dewey took a place of honour. Dewey

presented a paradigmatic set of recommendations designed for developing

societies that are moving towards modernity in his "Report and

Recommendation for the Turkish educational system." Mustafa

Kemal constantly tried to generate media to propagate modern education

during this period. He instigated official education meetings called

"Science Boards" and "Education Summits." The quality of education,

training issues and certain basic educational principles were discussed

at these meetings. On

August 11, 1930, Mustafa Kemal decided to try a multiparty movement

once again and asked Ali Fethi Okyar to establish a new party. He

insisted on the protection of secular reforms. The brand-new Liberal Republican Party succeeded

all around the country. Without the establishment of a real political

spectrum, once again, the party became the center to opposition of

Atatürk's reforms, particularly in regard to the role of religion

in public life. On December 23, 1930, a chain of violent incidents

occurred, starting with the rebellion of Islamic fundamentalists in Menemen, a small town in the Aegean region. This so-called Menemen Incident was considered a serious threat against secular reforms. In

November 1930, Ali Fethi Okyar dissolved his own party after seeing the

rising fundamentalist threat. Mustafa Kemal never succeeded in

establishing a long lasting multi-party parliamentary system. A more

lasting multi-party period of the Republic of Turkey began in 1945. In 1950 the RPP released the majority position to the Democratic Party. There are arguments that Kemal did not promote direct democracy by dominating the country with his single party rule. The reason behind the failed experiments with pluralism during

this period was that not all groups in the country had agreed to a

minimal consensus regarding shared values (mainly secularism) and

shared rules for conflict resolution. In response to such criticisms,

Mustafa Kemal's biographer Andrew Mango said:

"between the two wars, democracy could not be sustained in many

relatively richer and better-educated societies. Atatürk's

enlightened authoritarianism left a reasonable space for free private

lives. More could not have been expected in his lifetime." Even though, at times, he did not appear to be a democrat in his actions, he always supported the idea of eventually building a civil society;

a system of totality of voluntary civic and social organizations and

institutions that form the basis of a functioning society as opposed to

the force-backed structures of the state.

Beginning in 1932, several hundred "People's Houses" (Turkish: Halk Evi)

and "People's Rooms" (Halk Odası) across the country allowed greater

access to a wide variety of artistic activities, sports, and other

cultural events. The visual and the plastic arts, whose developers had, on occasion, been arrested by some Ottoman officials claiming that the depiction of the human form was idolatry,

were now highly encouraged and supported by Atatürk. Many museums

were opened, architecture began to follow modern trends, and classical Western music, opera, and ballet, as well as the theatre, also took greater hold. Book and magazine publications increased as well, and the film industry began to grow. In 1932, the first Qur'an in the Turkish language was read in front of the public. Mustafa Kemal commissioned Elmalılı Hamdi Yazır for a Qur'an translation. Yazir authored the tafsir "Hak Dini Kur'an Dili." His highest goal in the religious field was the translation of the Qur'an into Turkish. He wanted to "teach religion in Turkish to Turkish people who had been practicing Islam without understanding it for centuries" The Turkish Qur'an was fiercely opposed by religious people. It was only in 1935 that the version read in public found its way to print. Mustafa

Kemal believed that the understanding of religion was too important to

be left to a small group of people. This included the central religious text of

Islam. Mustafa Kemal's objective was to make the Qu'ran accessible and

modern. By 1936, the Qur'an had already been translated into 102

languages. There is a debate if Mustafa Kemal's Turkish Qur'an is the first. There was a polyglot Qu'ran written in Arabic, Persian, Turkish and Latin in the tetrapla style. This version of the Qu'ran was prepared by savant Andrea Acolutho of Bernstadt and printed at Berlin in 1701. Arguments

concentrate on the previous rare translations, besides being rare, if

able to be comprehended by common Turkish people as some used a variant

of the Turkish language the Ottoman Turkish language. On December 5, 1934, Turkey moved to grant full political rights to women. It was well before several other European nations. The equal rights of women in marriage had already been established in the earlier Turkish civil code. However, the change was not easy; in the 1935 elections there were only 18 female MPs out of a total of 395 representatives. Atatürk's foreign policy was aligned with his motto, "peace at home and peace in the world." a perception of peace linked to his project of civilization and modernization. The

base and the expected outcomes of Kemal's policies depended on the

power of the parliamentary sovereignty (justice, moral superiority, and

social structure of the nation) that was established by the Republic. The

Turkish War of Independence was the last time Atatürk used his

military might in dealing with other countries. Foreign issues were

resolved by peaceful methods during his presidency. The "Issue of Mosul" was one of the first foreign affairs-related controversies of the new Republic. It was a dispute with the United Kingdom over the control of the Mosul Province. During the Mesopotamian campaign,

General Marshall followed the British War Office's instruction that

"every effort was to be made to score as heavily as possible on the

Tigris before the whistle blew" and captured Mosul three days after the

signature of the Armistice of Mudros (30 October 1918). In 1920, the Misak-ı Milli,

which consolidated the "Turkish lands" based on a common past, history,

concept of morals and laws, declared that the Mosul Province was a part

of the historic Turkish heartland. The British were in a precarious

situation with the Issue of Mosul, and were adopting almost equally desperate measures to protect their interests. The Iraqi revolt against the British was put down by the RAF Iraq Command during the summer of 1920. Presumably, from a British perspective, if Mustafa

Kemal Atatürk succeeded in securing stability on his side, he

would have turned his attention to recovering Mosul and penetrate into

Mesopotamia, where the native population would probably join him. Thus,

an insurgent and hostile Muslim nation would be brought up to the very

gates of India. In 1923, Mustafa Kemal tried to persuade the GNA that

accepting the arbitration of the League of Nations at the Treaty of Lausanne over

the Mosul did not mean giving up Mosul, but rather waiting for a time

when Turkey might be stronger. The artificially drawn border had an

unsettling effect on both sides of the population. Later, it was

claimed that Turkey began where the oil ends as the border was drawn by

the British geophysicists based on the oil reserves. Atatürk did

not want this separation. The

British Foreign Secretary attempted to disclaim any existence of oil in

the Mosul area. On 23 January 1923, Lord Curzon argued that the

existence of oil was no more than hypothetical. However, according to Armstrong, "England wanted oil. Mosul and Kurds were the key." While three inspectors from the League of Nations Committee were sent to the region to oversee the situation in 1924, the Sheikh Said rebellion,

beginning in 1924 and escalating until 1927, broke out to establish a

new government positioned to cut Turkey's link to Mesopotamia. The

relationship between the rebels and Britain was questioned. British

assistance was sought after the rebels realised that the rebellion, or

its expected outcome, could not stand by itself. In

1925, the League of Nations formed a three-member committee to study

the case while the Sheikh Said Rebellion was on the rise. Partly

because of the continuing uncertainties along the northern frontier

(present-day northern Iraq), the committee recommended that the region

should be connected to Iraq with the condition that the UK would hold

the British Mandate of Mesopotamia.

By the end of March 1925, the necessary troop movements were completed,

and the whole area of the Sheikh Said rebellion was encircled. As

a result of these maneuvers, the revolt was put down. Britain, Iraq and

Kemal made a treaty on 5 June 1926, which mostly followed the decisions

of the League Council. In 1926, Kemal faced growing opposition to his

reform policies, a continuing precarious economic situation, and a

defeat in the Mosul issue. A large section of the Kurdish population

and the Iraqi Turkmen were

left on the other side of the border. The Sheikh Said Rebellion

hastened both the imposition of the Republican Party and the speed of

Atatürk's reforms. In 1925, the population was largely illiterate

and disparate. Turkey was in ruins, reconstruction was difficult,

poverty was everywhere and people were in pain, which easily fed

separatist violence. Mustafa

Kemal attributed the rebellion to certain notables rather than a

section of the population, who had been found guilty by the courts

(kanunen mucrim olan bazi muteneffizan) and who used the mask of

religion to conceal the interests of landlords, feudal tribal leaders

and other "reactionaries" on 7 March 1925. Mustafa Kemal wanted positive relations with his country's northern neighbor. He signed the Treaty of Moscow with Soviet Russia.

The relations were cordial but had a distinct character of the common

interests. The basic character of their relationship during Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's leadership of the independence war was based on the fact that they were fighting against a common enemy: Britain and the West. He cooperated with the Soviets during the war of independence in order to establish the new state. These

cordial relations were tested during the Issue of Mosul. Curzon

insisted during the Lausanne Conference (1923) that Mosul belonged to

Iraq, and it would be under the British Mandate of Mesopotamia.

In 1923, Kemal refused to accept this position, and on the same day

signed a non-aggression and security pact with Soviet Russia in Paris.

This pact remained in effect until it was unilaterally abrogated by the

Soviet Union in 1945. The Soviet War Minister Kliment Voroshilov was invited to the tenth year celebrations by Mustafa Kemal. Kemal

explained his position regarding the realization of his plan for a

Balkan Federation economically uniting Turkey, Greece, Romania,

Yugoslavia and Bulgaria. The visit was historically important, as no

member of the Politburo or Steering Committee of Moscow's ruling Communist Party had ventured outside the Soviet Union since it was founded. During

the second half of the 1930s, Mustafa Kemal tried to establish a closer

relationship with Britain in an effort to improve relations with the

West. Franklin D. Roosevelt quoted the Foreign Affairs Minister of the Soviet Union, Maxim Litvinov:

"Litvinov told me that the most valuable and interesting leader in the

world does not live in Europe but beyond the Straits in Ankara and that

he was the President of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal." The post-war leader of Greece, Eleftherios Venizelos, was also determined to establish normal relations between the two states. The war had devastated the lands of Western Anatolia, and the financial burden of Ottoman Muslim refugees from

Greece brought obstacles to the rapprochement. Venizelos moved forward

with the agreement despite accusations of making too many concessions

on the issues of the naval armaments, and the properties of the Ottoman

Greeks from Turkey according to the Treaty of Lausanne. Similarly,

Kemal resisted the pressures of historic emnities or atrocity-mongering

between the societies. In spite of Turkish animosity against the

Greeks, Kemal showed acute sensitivity to even the slightest allusion

to these tensions. Greece renounced all its claims over Turkish territory and the two

sides concluded an agreement on 30 April 1930. On 25 October, Venizelos

visited Turkey, and signed a treaty of friendship. Venizelos even forwarded Atatürk's name for the 1934 Nobel Peace Prize. Even after his fall from power, Greco-Turkish relations remained cordial. Indeed, Venizelos' successor Panagis Tsaldaris came to visit Atatürk in September 1933 and signed a more comprehensive agreement, called the Entente Cordiale, a stepping stone for the Balkan Pact. Mustafa Kemal was implementing his reforms, when he found cooperation with Afghanistan. Afghanistan was in the midst of a reformation period under Amanullah Khan. Afghan Foreign Minister Mahmud Tarzi was a follower of Mustafa Kemal's domestic policy. He encouraged Amanullah Khan in

social and political reform but urged that reforms should be gradually

built upon the basis of a strong government. During the late 1920s,

Anglo-Afghan relations soured over British fears of an Afghan-Soviet

friendship. On 20 May 1928, Anglo-Afghan politics gained a positive

perspective, when Amanullah Khan and the Queen were received by Mustafa

Kemal in Istanbul. This meeting was followed by a Turkey-Afghanistan

Friendship and Cooperation pact on 22 May 1928. Mustafa Kemal supported

Afghanistan's integration into international organizations. In 1934

Afghanistan's relations with the international community gained a huge

boost when it joined the League of Nations. In 1937, King Zahir Shah became

a signatory of the Treaty of Saadabad. Mahmud Tarzi received Mustafa

Kemal's personal support until he died on 22 November 1933 in Istanbul. Mustafa Kemal and Reza Shah had a common approach regarding British imperialism and

its influence in their region. This climate created a slow but

continuous rapprochement between Ankara and Tehran. Both governments

sent diplomatic missions and messages of friendship to each other

during the Turkish war of independence. The

policy of the Ankara government in this period was to give moral

support in order to assure Iranian independence and territorial

integrity. The relations were strained after the abolishment of the Caliphate. Iran's Shi'a clergy did

not accept Kemal's position. Iranian religious power centers perceived

the real motive behind Atatürk's reforms was to undermine the

power of the clergy. An

admirer of Mustafa Kemal and close student of his reforms, Reza Shah

followed the same type of modernization efforts. By the mid-1930s, Reza

Shah's efforts had caused intense dissatisfaction to the clergy throughout Iran, thus widening the gap between religion and government. Mustafa Kemal feared the occupation and dismemberment of Iran as a multi-ethnic/multi-tribal society by Russia or Great Britain. Like

Mustafa Kemal, Reza Shah wanted to secure Iran's borders. Reza Shah

visited him in 1934. In 1935 the draft of what would become the

Saadabad Pact was paragraphed in Geneva, but the signing of it was

delayed because of the border dispute between Iran and Iraq. Iran challenged the validity of both the Treaty of Erzerum and the Constantinople Protocol in 1934. On 8 July 1937, the Saadabad Pact was signed at Tehran by

Turkey, Iraq, Iran and Afghanistan. The signatories undertook to

preserve their common frontiers, to consult together in all matters of

common interest and to commit no aggression against one another’s

territory. The treaty united common points between the Afghan king’s

call for greater Oriental-Middle Eastern Cooperation, Reza Shah's goal

in securing relations with Turkey that would help Iran free herself

from Soviet and British influence, and Mustafa Kemal's foreign policy

based on common interest to secure stability in the region. The

immediate outcome was to deter Mussolini from adventures in the region. On July 24 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne included the Lausanne Straits Agreement. The Lausanne Straits Agreement stated that the Dardanelles should

remain open to all commercial vessels: seizure of foreign war vessels

was subject to certain limitations during peacetime, and, even as a

neutral state, Turkey could not limit any military passage during

wartime. The Lausanne Straits Agreement stated that the waterway was to

be demilitarized, the management of the waterway to be left to the

Straits Commission. The demilitarized zone heavily restricted Turkey's

domination and sovereignty over the Straits. The defence of Istanbul was impossible without having the sovereignty over the water that passed through it. In

March 1936, Hitler's reoccupation of the Rhineland gave Mustafa Kemal

the opportunity to resume full control over the Straits. "The situation

in Europe", he declared "is highly appropriate for such a move. We

shall certainly achieve it". Tevfik Rüştü Aras,

who was the foreign minister, initiated a move to revise the Straits'

regime. Aras claimed that he was directed by the President, rather than

his Prime Minister, Ismet Inönü. Inōnü was worried about

harming the relations with Britain, France, and Balkan neighbors over

the Straits. However, the signatories agreed to join the conference,

since unlimited military passage had become unfavorable to Turkey with

the changes in world politics. Mustafa Kemal demanded that the members

of the Turkish Foreign Office devise a solution that would transfer

full control over the waterway to Turkey. Until

the early 1930s, Turkey followed a modern neutral foreign policy with

the West by developing joint friendship and neutrality agreements.

These bilateral agreements were aligned with Mustafa Kemal's worldview.

By the end of 1925, Turkey had signed fifteen joint agreements with

Western states. In

the early 1930s, changes and developments in world politics required

Turkey to make multilateral agreements to improve its security. Mustafa

Kemal strongly believed that a close cooperation between the Balkan

states based on the principle of equality would have an important

effect on European politics. These states had been ruled by the Ottoman

Empire for centuries, and had formed a powerful force. While the

origins of the Balkan agreement may date back as far as 1925, the

Balkan Pact came to being in the mid-1930s. Several important

developments in the Balkan Peninsula and in Europe helped the original

idea to materialize. In inter-Balkan relations, improvements in the

Turkish-Greek alliance and the rapprochement between Bulgaria and

Yugoslavia are worth mentioning. The Balkan Pact was

negotiated by Mustafa Kemal with Greece, Romania, and Yugoslavia. This

mutual-defence agreement intended to guarantee the signatories'

territorial integrity and political independence against attack by

another Balkan state such as Bulgaria or Albania. It countered the

increasingly aggressive foreign policy of fascist Italy and the effect

of a potential Bulgarian alignment with Nazi Germany. He thought of the

Balkan Pact as a medium of balance in the relations with the European

countries. Mustafa

Kemal was particularly anxious to establish a region of security and

alliances in the west of Turkey and in Balkan Europe, which would

extend as far as Dobruja. It

was signed by GNA on Feb 28. The Greek and Yugoslav Parliaments

ratified the agreement a few days later. The unanimously ratified

Balkan pact became a reality on 18 May 1935 and lasted until 1940. The

Balkan Pact turned out to be an ineffective organization for reasons

that were beyond Atatürk’s control. What he wanted to prevent with

the Balkan Pact was realized by Bulgaria’s attempt to put the Dobruja

issue into the agenda after a series of international events ended with

the Italian invasion of Albania on 7 April 1939. These conflicts spread rapidly, ending with World War II.

The goal of Atatürk, to protect southeast Europe, failed with the

dissolution of the pact. Turkish Prime-Minister Ismet Inonu was

very conscious of foreign policy issues. During the second half of the

1930s, Atatürk tried to form a closer relationship with Britain.

The given risks of this policy change put the two men at odds. The

Hatay issue and the Lyon agreement were two important developments in

foreign policy that played a significant role in the severing of

relations between Atatürk and Ismet. In 1936 Atatürk raised the "Issue of Hatay" at the League of Nations. Hatay was based on the old administrative unit of the Ottoman Empire called the Sanjak of Alexandretta.

On behalf of the League of Nations, the representatives of France, the

United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Belgium and Turkey prepared a

constitution for Hatay, which established it as an autonomous sanjak within Syria. Despite some inter-ethnic violence, in the midst of 1938 an

election was conducted by the local legislative assembly. The cities of Antakya (Antioch) and İskenderun (Alexandretta) joined Turkey in 1939.

Mustafa

Kemal instigated economic policies not just to develop small and large

scale businesses, but also to create social strata (industrial bourgeoisie along with the peasantry of

Anatolia) that were virtually non-existent during the Ottoman Empire.

The primary problem faced by the politics of his period was the lag in

the development of political institutions and social classes which

would steer such social and economic changes. Mustafa Kemal's vision regarding early Turkish economic policy was apparent during the İzmir Economic Congress of 1923 which was established before the signing of the Lausanne Treaty. The initial choices of Mustafa Kemal's economic policies were a reflection of the realities of his period. After World War I,

due to the lack of any real potential investors to open private sector

factories and develop industrial production, Kemal's activities

regarding the economy included the establishment of many state-owned

factories for agriculture, machinery, and textile industries. Mustafa Kemal and İsmet İnönü had

a national vision in their pursuit of the state controlled economical

polices. Kemal and İsmet wanted to knit the country together, eliminate

the foreign control of the economy, and improve communications.

Istanbul, a trading port with international foreign enterprises, was

deliberately abandoned and resources were channeled to other,

relatively less developed cities, in order to establish a more balanced

development throughout the country. For Mustafa Kemal, as for his supporters, tobacco remained wedded to his policy in the pursuit of economic independence. Turkish tobacco was an important industrial crop, while its cultivation and manufacture were French monopolies under capitulations of the Ottoman Empire.

The tobacco and cigarette trade was controlled by two French companies:

the "Regie Compagnie interessee des tabacs de l'empire Ottoman" and

"Narquileh tobacco." The Ottoman Empire gave the tobacco monopoly to the Ottoman Bank as a limited company under the "Council of the Public Debt".

Regie, as part of the Council of the Public Debt, had control over

production, storing, and distribution (including export) with an

unchallenged price control. Consequently, Turkish farmers were

dependent on the company for their livelihood. In 1925, this company was taken over by the state and named "Tekel". The control of tobacco was the biggest achievement of the Kemalist political machinery's "nationalization"

of the economy for a country that did not produce oil. They accompanied

this achievement with the development of the cotton industry, which

peaked during the early 1930s. Cotton was the second biggest industrial

crop in Turkey. In 1924, with the initiative of Mustafa Kemal, the first Turkish bank İş Bankası was

established. He was the first member of İş Bankası. The bank was a

response to the growing need for a truly national establishment and the

birth of a banking system which was capable of backing up economic

activities, managing funds accumulated as a result of policies

providing savings incentives and, where necessary, extending resources

which could trigger industrial impetus. In 1927, Turkish State Railways was established. Because Mustafa Kemal considered the development of a national rail network as

another important step in industrialization, it was given high

priority. This institution developed an extensive railway network in a

very short time. In 1927, Kemal also ordered the integration of road

construction goals into development plans. The road network consisted

of 13,885 km of ruined surface roads, 4.450 km of stabilized

roads, and 94 bridges. In 1935, a new entity was established under the

government called "Sose ve Kopruler Reisligi" which would be the

driving force of new roads after the World War II. However, in 1937 the

22,000 km of roads in Turkey were mainly a system to aid the

railways. The young republic, like the rest of the world, found itself in a deep economic crisis during the Great Depression.

Mustafa Kemal reacted to conditions of this period by moving toward

integrated economic polices, and establishing a central bank to control

exchange rates. However, Turkey could not finance essential imports;

its currency was shunned and zealous revenue officials seized the

meager possessions of peasants who could not pay their taxes. In 1929, Mustafa Kemal signed a treaty that resulted in the restructuring of the nation's debt with the Ottoman Public Debt Administration.

He did not fault the Ottoman debt. He had to deal with the turbulent

economic issues of the Great Depression along with the payment of the

high debt known as the Ottoman public debt.

Until the early 1930s, Turkish private business could not acquire

exchange credits. It was impossible to integrate the Turkish economy

without a solution to this problem. This increased the credibility of

the new Republic. In 1931, Mustafa Kemals's intention to establish the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey was realized. The main intention behind the bank was to have control over the exchange rate. The Ottoman Bank's role during its initial years as a central bank was slowly ceased. Later specialized banks such as the Sümerbank (1932) and the Etibank (1935) were founded. From the political economy perspective,

Mustafa Kemal had to face the same problems which all countries faced:

political upheaval. The establishment of a new party with a different

economic perspective was needed. He asked Ali Fethi Okyar to fulfill

this need. The Liberal Republican Party (August,

1930) came out with a liberal program and proposed that state

monopolies should be ended, foreign capital should be attracted, and

that state investment should be curtailed. Mustafa Kemal supported

İnönü's point of view: "it is impossible to attract foreign

capital for essential development." In 1931, he proclaimed: "In the

economic area ...the programme of the party is statism." However, the effect of free republicans was felt strongly and state intervention became more moderate, more akin to a form of state capitalism. One of his radical left-wing supporters, Yakup Kadri Karaosmanoğlu from the Kadro (The Cadre) movement, claimed that Mustafa Kemal found a third way between capitalism and socialism. The

first (1929-1933) and second five year economic plans were performed

under the supervision of Mustafa Kemal. The first five year economic

plan promoted consumer substitution industries. However, these economic

plans changed drastically with the death of Kemal and the rise of World War II. Subsequent governments took measures that harmed the economic productivity of Turkey in various ways. The

achievements of the 1930s were credited to early (1920s) implementation

of the economic system based on the national policies of Mustafa Kemal

and his team. In

1931, Mustafa Kemal watched the first national aircraft MMV-1. He

realized the important role of aviation. In his words, "the future lies

in the skies". Turkish Aeronautical Association was founded in February 16, 1925 by his directive. He

ordered the establishment of the Turkish Aircraft Association Lottery.

Instead of the traditional raffle prizes, this new lottery paid money

prizes. The major part of its income was transferred to establish a new

factory. The income from this lottery was used in funding aviation

projects. Mustafa Kemal did not see the flight of the first Turkish

military aircraft built at the factory. Operational American Curtiss Hawk fighters were being produced soon after his death and before the onset of World War II. In 1932, liberal economist Celal Bayar became the Minister of Economy at Mustafa Kemal's request and served until 1937. During

this period, the country moved toward mixed economy with first private

initiatives. Textile, sugar, paper and steel factories (financed by a

loan from England) were the private sectors of the period. Besides

these government owned power plants, banks, and insurance companies

were established. In 1935, the first Turkish cotton print factory

"Nazilli Calico print

factory" opened. Cotton planting was promoted to furnish raw material

for future factory settlements, part of the industrialization process. One of the centers for factory settlements was Nazilli. Nazilli become a major center beginning with the establishment of cotton mills and was followed by a calico print factory by 1935. On 25 October 1937, Mustafa Kemal appointed Celal Bayar as

the prime minister of the 9th government. Integrated economic policies

reached their peak with the signing of the 1939 Treaty with Britain and

France. This signaled a turning point in Turkish history. It was the first step towards an alliance with the "West". Celal

Bayar served as prime minister until Mustafa Kemal's death. The

differences of opinion between Inönü (state control) and

Celal Bayar (liberal) came to the forefront after İnönü

became president in 1938. On 25 January 1939, Prime Minister Bayar

resigned. Mustafa

Kemal supported the establishment of the automobile industry. He wanted

it to become a center in the region. The motto of the Turkish automobile association was: "The Turkish driver is a man of the most exquisite sensitivities." During 1935, Turkey was becoming an industrial society on the Western European model set out by Atatürk. At

the time of his death, most regions of Turkey had viable micro-economic

stability and some macro economic stability. These signs of sound

economic policies were marked by the first-ever emergence of local

banks. However, the gap between Mustafa Kemal’s goals and the

achievements of the socio-political structure of the country was not

closed. On 29 January 1923, Mustafa Kemal married Latife Uşaklıgil; they were divorced on August 5, 1925. He

never remarried. During his lifetime, Atatürk adopted seven

daughters and a son. In his leisure time, he enjoyed reading and

writing (books and a personal journal), horseback riding, chess, and

swimming. He was also an avid dancer and enjoyed both the waltz and

traditional Zeybek folk dances. During 1937, indications that Atatürk's health was worsening started to appear. In early 1938, while he was on a trip to Yalova, he suffered from a serious illness. He went to İstanbul for treatment, where he was diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver due to heavy alcohol consumption. During

his stay in İstanbul, he made an effort to keep up with his regular

lifestyle for a while. He died on 10 November 1938, at the age of 57,

in the Dolmabahçe Palace, where he spent his last days. The

clock in the bedroom where he died is still set to the time of his

death, 9:05 in the morning. Atatürk's funeral called forth both

sorrow and pride in Turkey, and seventeen countries sent special

representatives, while nine contributed with armed detachments to the cortège. Mustafa Kemal's remains were originally laid to rest in the Ethnography Museum of Ankara, and transferred on 10 November 1953, 15 years after his death, in a 42-ton sarcophagus, to a mausoleum that overlooks Ankara, Anıtkabir. In his will,

he donated all of his possessions to the Republican People's Party,

providing that the yearly interest of his funds would be used to look

after his sister Makbule and his adopted children, and fund the higher

education of the children of İsmet İnönü. The remainder of

this yearly interest was willed to the Turkish Language Association and the Turkish Historical Society.

On July 20 1936, the Montreux Convention was

signed, with the participation of Bulgaria, Great Britain, Australia,

France, Japan, Romania, the Soviet Union, Turkey, Yugoslavia and

Greece. It became the primary instrument, a legal cornerstone, that

governed the passage of commercial and war vessels through the

Dardanelles Strait. It was ratified by the GNAT

on 31 July 1936. It went into effect on 9 November 1936, and is still valid today.