<Back to Index>

- Philosopher John Stuart Mill, 1806

- Novelist Honoré de Balzac, 1799

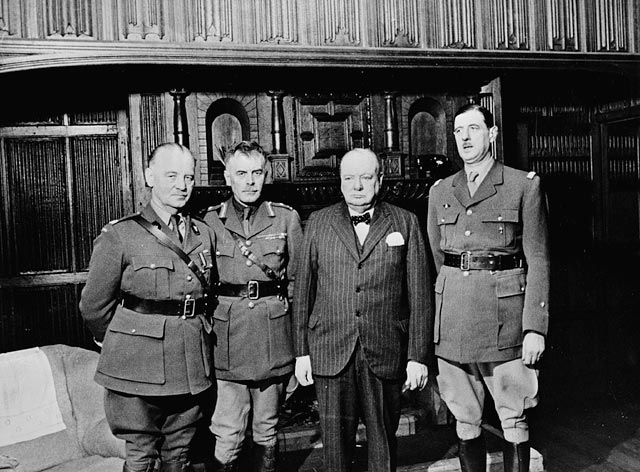

- Prime Minister of the Republic of Poland Władysław Eugeniusz Sikorski, 1881

Władysław Eugeniusz Sikorski (May 20, 1881 – July 4, 1943) was a Polish military and political leader. He was born in Tuszów Narodowy, a village in the present-day Subcarpathian Voivodeship of south-eastern Poland, which at the time was part of Austria-Hungary, one of Poland's three partitioners. Prior to World War I,

he established and participated in several underground organizations

that promoted the cause of Polish independence. He fought with

distinction in the Polish Legions during World War I, and later in the newly created Polish Army during the Polish-Soviet War (1919 to 1921). In that war he played a prominent role in the decisive Battle of Warsaw, when Soviet forces, expecting an easy final victory, were surprised and routed by the Polish counterattack. In the early years of the Second Polish Republic, Sikorski held government posts including prime minister (1922 to 1923) and minister of military affairs (1923 to 1924). Following Józef Piłsudski's May Coup (1926) and the installation of the Sanacja government,

he fell out of favor with the new regime. Up until, and throughout

1939, he remained in the opposition, and wrote several books on the art

of warfare and on Polish foreign relations. During World War II he became Prime Minister of the Polish Government in Exile, Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Armed Forces, and a vigorous advocate of the Polish cause on the diplomatic scene. He supported the reestablishment of diplomatic relations between Poland and the Soviet Union, which had been severed after the Soviet alliance with Germany in the 1939 invasion of Poland. In April 1943, however, Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin broke off Soviet-Polish diplomatic relations following Sikorski's request that the International Red Cross investigate the Katyń massacre. In July 1943, Sikorski was killed in a plane crash into the sea immediately on takeoff from Gibraltar. The exact circumstances of his death remain in dispute, which has given rise to conspiracy theories, however, investigators have concluded that Sikorski's injuries were consistent with a plane crash. Sikorski was born in Tuszów Narodowy, Galicia, at the time Austro-Hungarian Empire. His father was Tomasz Sikorski, of impoverished Polish nobility (bearing Clan Kopaszyna coat-of-arms and apparently descended from it); his mother was Emilia Habrowska. In 1898 he joined Konarski's High School in Rzeszów,

but his mother later interrupted his studies there and sent him to a

teacher's seminar. In 1902 he passed a final high school exam in Lwów. Starting that year, young Sikorski studied engineering at the Lwów Polytechnic, specializing in road and bridge construction. After graduation he worked for the Galician administration in the petroleum industry. In 1906 Sikorski volunteered for a year's service in the Austro-Hungarian army and attended the Austrian Military School, obtaining an officer's diploma and becoming a reserves second lieutenant (podporucznik rezerwy). In 1909 he married Olga Helena Zubrzewska. In 1907 Sikorski joined the underground Polish Socialist Party (Polska Partia Socjalistyczna), which was intent on securing Polish independence. It was then that he met Józef Piłsudski. Having a military education, he lectured other activists on military tactics. In 1908, in Lwów, Sikorski—together with Marian Kukiel, Walery Sławek, Kazimierz Sosnkowski, Witold Jodko-Narkiewicz and Henryk Minkiewicz—organized the secret Combat Association (Związek Walki Czynnej), directed at organizing an uprising against the Russian Empire, one of Poland's three partitioners. In 1910, likewise in Lwów, Sikorski organized a Riflemen's Association (Związek Strzelecki) and became responsible for military organization within the Commission of Confederated Independence Parties (Komisja Skonfederowanych Stronnictwo Niepodległościowych).

Upon the outbreak of World War I in 1914, he became chief of the military department in the Supreme National Committee (Naczelny Komitet Narodowy) and remained in this post until 1916. Later, as a commissioner of the Polish Legions in Kraków, he was responsible for recruitment to the Legions, an army created by Józef Piłsudski to liberate Poland from Russian and,

ultimately, Austro-Hungarian and German rule. The Legions initially

fought in alliance with Austro-Hungary against Russia. From 1916 there

was growing tension between Sikorski, who advocated cooperation with

Austro-Hungary, and Piłsudski, who felt that Austro-Hungary and Germany

had betrayed the trust of the Polish people. In June 1917 Piłsudski

refused Austro-Hungarian orders to swear loyalty to the

Austro-Hungarian emperor (the "oath crisis", kryzys przysięgowy) and was interned at the fortress of Magdeburg,

while Sikorski returned to the Austro-Hungarian Army. Although in 1918

Sikorski came to agree with Piłsudski (and soon joined Piłsudski in

internment), from then on the two great Polish leaders would drift

farther apart. In

1918 the Russian, Austro-Hungarian and German empires collapsed, and

Poland once again became independent, but the borders of the Second Polish Republic were not stable. On the east they would be determined in escalating conflicts among Polish, Ukrainian, Lithuanian and Soviet forces in what culminated in the Polish-Soviet War (1919–1921). After participating in the Polish-Ukrainian War, where troops under his command secured Przemyśl, in the opening phase of the Polish-Soviet War, Władysław Sikorski, now commander of the Polish Army in the Galicia region, took part in the liberation of Lwów and Przemyśl. Later Sikorski commanded the Polesie Group during Poland's Kiev offensive in early 1920. He had a good working relationship with French General Maxime Weygand of the Interallied Mission to Poland. In April 1920 the Red Army of Russia's new Soviet regime pushed back the Polish forces and invaded Poland. Subsequently Sikorski failed to hold the Brest fortress, but then distinguished himself commanding the Polish 5th Army (the Lower Vistula front) during the Battle of Warsaw.

At that time the Soviet forces, expecting an easy final victory, were

surprised and crippled by the Polish counter-attack. During that battle

(sometimes referred to as "the Miracle at the Vistula") Sikorski

stopped the Bolshevik advance north of Warsaw and gave Józef Piłsudski the

time he needed for his counter-offensive; for his valorous achievements

Sikorski received the highest Polish military decoration, the order of Virtuti Militari. After the Battle of Warsaw, Sikorski commanded the 3rd Army during the latter stages of the Battle of Lwów and the Battle of Zamość, and then after the battle of Niemen advanced with his forces toward Latvia and deep into Belarus. The Poles defeated the Soviets, and the Polish-Soviet Treaty of Riga (March 1921) gave Poland substantial areas of Belarus and Ukraine (Kresy).

Sikorski's fame was enhanced as he became known to the Polish public as

one of the heroes of the Polish-Soviet War. He would describe his role

in the war in a 1923 book, Nad Wisłą i Wkrą (At the Wisła and Wkra Rivers). In April 1921 Sikorski succeeded Piłsudski as commander-in-chief of the Polish Armed Forces, and became chief of the Polish General Staff. Between 1922 and 1925 he held high government offices. After the assassination of President of Poland Gabriel Narutowicz, the Marshal of the Sejm (the Polish parliament), Maciej Rataj, appointed Sikorski prime minister. From December 18, 1922, to May 26, 1923, Sikorski served as Prime Minister and also as Minister of Internal Affairs,

and was even considered as possible President. During his brief tenure

as prime minister, he became popular with the Polish public and carried

out essential reforms in addition to guiding the country's foreign

policy in a direction that gained the approval and cooperation of the League of Nations and tightened Polish-French cooperation. He obtained recognition for Poland's eastern frontiers from the UK, France and the United States. From 1923 to 1924 he held the post of Chief Inspector of Infantry (Generalny Inspektor Piechoty). From February 1924 to 1925, under Prime Minister Władysław Grabski, he was Minister of Military Affairs and guided the modernization of the Polish military; he also created the Korpus Ochrony Pogranicza. His proposal, however, to increase the powers of the Minister of Military Affairs while reducing those of the Chief Inspector of the Armed Forces met with sharp disapproval from Piłsudski, who at that time was gathering many opponents of the government. From 1925 to 1928 Sikorski commanded Military Corps District (Okręg Korpusu) VI in Lwów. A democrat and supporter of the Sejm, Sikorski maintained his neutrality during Józef Piłsudski's May coup d'état in 1926, which was supported by most of the military. In due course, as a semi-dictatorial Sanacja regime was

established, Sikorski joined the anti-Piłsudski opposition. In 1928 he

was dismissed by Piłsudski from public service and transferred into the

reserves. In 1936, together with several prominent Polish politicians (Wincenty Witos, Ignacy Paderewski, and General Józef Haller) he joined the Front Morges, an anti-Sanacja political grouping. Sikorski largely withdrew from politics, spending much of his time in Paris, France, and working with the French Ecole Superieure de Guerre (war college). On the basis of his experiences in the Polish-Soviet War, he wrote a book on the future of maneuver warfare, Przyszła wojna – jej możliwości i charakter oraz związane z nimi zagadnienia obrony kraju (War in the Future: Its Possibilities and Character and Associated Questions of National Defense,

Polish and French editions 1934, English edition 1943), foreseeing the

scale of the next World War and advancing ideas similar to the German

concept of Blitzkrieg ("lightning war"). Alongside France's Charles de Gaulle and Russia's Mikhail Tukhachevski, he may be considered one of the pioneers of Blitzkrieg theory.

While the book received little attention in Poland, it was closely

studied in other countries, especially Soviet Russia. During this period, he wrote several other books and many articles, foreseeing, among other things, the rapid militarization of Germany and the deleterious effects of Western appeasement policies.

As the international situation deteriorated, Sikorski returned to

Poland in 1938, hoping to be of more active service to his country. When Poland was invaded by Germany in September 1939, Sikorski was refused a military command by the Polish Commander in Chief, Marshal Edward Rydz-Śmigły. Sikorski escaped through Romania to Paris, where on September 28 he joined Władysław Raczkiewicz and Stanisław Mikołajczyk in a Polish government-in-exile, becoming from September 30 the Polish prime ministers in exile. He

preserved the continuity of his country’s government and was respected

and recognized by the population of occupied Poland. During his years

as prime minister in exile, Sikorski personified the hopes and dreams

of millions of Poles, as reflected in the saying, "When the sun is

higher, Sikorski is nearer" (Polish: "Gdy słoneczko wyżej, to Sikorski bliżej"). On November 7 he became Commander in Chief and General Inspector of the Armed Forces (Naczelny Wódz i Generalny Inspektor Sił Zbrojnych). His

government was recognized by the western Allies, as Poland, even with

its territories occupied, still commanded substantial armed forces: the Polish Navy had sailed to Britain, and many thousands of Polish troops had escaped via Romania and Hungary or across the Baltic Sea.

Those routes would be used until the end of the war by both interned

soldiers and volunteers from Poland, who jocularly called themselves

"Sikorski's tourists" and embarked on their dangerous journeys, braving

death or imprisonment in concentration camps if caught by the Germans or their allies. With the steady flow of recruits, the new Polish Army was soon reassembled in France and in French-mandated Syria. In 1940 the Polish Highland Brigade took part in the Battle of Narvik (Norway), and two Polish divisions participated in the defense of France, while a Polish motorized brigade and two infantry divisions were in process of forming. A Polish Independent Carpathian Brigade was created in French-mandated Syria, to which many Polish troops had escaped from Romania. The Polish Air Force in

France comprised 86 aircraft in four squadrons. One and a half of the

squadrons were fully operational, while the rest were in various stages

of training. At that time Poland was the third most powerful Ally, with

some 84,000 soldiers in France alone. Although many Polish personnel had died in the fighting or had been interned in Switzerland following the fall of France, General Sikorski refused French Marshal Philippe Pétain's proposal of capitulation to Germany. On June 19, 1940, Sikorski met with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and promised that Polish forces would fight alongside the British until final victory. Sikorski and his government moved to London and were able to evacuate many Polish troops to Britain. After the signing of a Polish-British Military Agreement on August 5, 1940, they proceeded to build up and train the Polish Armed Forces. Experienced Polish pilots took part in the Battle of Britain, where the Polish 303 Fighter Squadron achieved the highest number of kills of any Allied squadron. After the creation of the pro-German Vichy government in

France and the ensuing split of French forces, the Polish Army in the

United Kingdom and the Middle East became the second largest Allied

army after that of the United Kingdom. Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union ("Operation

Barbarossa") in June 1941, General Sikorski was among the first to

realize that the complexion of the war had drastically changed.

Strongly encouraged by British Foreign Office diplomat Anthony Eden, Sikorski on July 30, 1941, opened negotiations with the Soviet ambassador to London, Ivan Maisky, to re-establish diplomatic relations between Poland and the Soviet Union, which had been broken off after the Soviet invasion of Poland in September 1939. Later that year, Sikorski went to Moscow with a diplomatic mission (including the future Polish ambassador to Moscow, Stanisław Kot, and chief of the Polish Military Mission in the Soviet Union, General Zygmunt Szyszko-Bohusz). Sikorski was the architect of the agreement reached by the Polish Government with the Soviet Union (the Sikorski-Maisky Pact of August 17, 1941), confirmed by Joseph Stalin in December of that year. Stalin agreed to invalidate the September 1939 Soviet-German partition of Poland, declare the Russo-German Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939 null

and void, and release tens of thousands of Polish prisoners-of-war held

in Soviet camps. Pursuant to an agreement between the Polish

government-in-exile and Stalin, the Soviets granted "amnesty" to many Polish citizens, from whom a 75,000-strong army (the Polish II Corps) was formed under General Władysław Anders and later evacuated to the Middle East,

where Britain faced a dire shortage of military forces. The whereabouts

of thousands more Polish officers, however, would remain unknown for

two more years, and this would weigh heavily on both Polish-Soviet

relations and on Sikorski's fate. Nonetheless,

Sikorski soon realized that the Soviet Union had plans for Polish

territories, which would be unacceptable to Polish public. The Soviets

began their diplomatic offensive after their first major military

victory in the Battle of Moscow. In January 1942 the Soviets through diplomatic channels revealed their claims to the city of Lwow. On January 26, British diplomat Stafford Cripps informed General Sikorski that while Stalin planned to extend Polish borders to the west, by giving Poland Germany’s East Prussia, he also wanted to considerably push Poland’s eastern frontier westwards, along the lines of the Versailles concept of the Curzon Line. Sikorksi's

stance on eastern borders was not inflexible; in a memo to US President

Roosevelt in December 1942 he anticipated losses in the east and

proposed that the Polish-German border should be pushed much further to

the west, with Poland occupying "the zone up to the Oder and Lusatian

Neisse with bridegeheads on the left bank". This

position alienated the US-Polish community; labelled as an appeaser by

some groups and striving for support from Roosevelt, he issued a

statement in December 1942 that the war was "not about borders." Sikorski met with British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden in

January 1942 to discuss Poland's future. He linked its security with

that of Europe as a whole, and proposed the creation of a new

Polish-Lithuanian union, to be governed by an English prince. He also

stated that "It is quite impossible...for Poland to continue to

maintain 3.5 million Jews after the war. Room must be found for them

elsewhere." In

1943 the fragile relations between the Soviet Union and the Polish

government-in-exile finally reached their breaking point when, on April

13, the Germans announced the discovery of the bodies of 4,000 Polish

officers who had been murdered by the Soviets and buried in Katyn

Forest, near Smolensk, Russia. Stalin claimed that the atrocity had been carried out by the Germans, while Nazi propaganda orchestrated by Joseph Goebbels successfully exploited the Katyn massacre to drive a wedge between Poland, the Western Allies and the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union/Russia didn't acknowledge its responsibility for this and similar massacres of Polish officers until the 1990s. When Sikorski refused to accept the Soviet explanation and requested an investigation by the International Red Cross on April 16, the Soviets accused the government-in-exile of cooperating with Nazi Germany and broke off diplomatic relations on April 26. At that time the intentions of the Soviet Union become clear: Stalin wanted the recognition of his recent annexation of the Baltic states, and redrawing the Polish-Soviet border at the Curzon Line, which the government-in-exile would never accept, as it would mean the loss of about a third of Poland's territory. The Soviets were able to sever relations with the Polish government-in-exile by exploiting controversy over

an atrocity which they had themselves committed against Polish forces.

They were also able to clear the way for a postwar communist-sponsored

Polish government (PKWN)

which would yield compliantly to Soviet demands. Stalin soon began a

campaign for recognition by the Western Allies of a Soviet-backed

Polish government led by Wanda Wasilewska, a dedicated communist with a seat in the Supreme Soviet, with General Zygmunt Berling, commander of the 1st Polish Army in Russia, as commander-in-chief of all Polish armed forces. On July 4, 1943, while Sikorski was returning from an inspection of Polish forces deployed in the Middle East, he was killed, together with his daughter, his Chief of Staff, Tadeusz Klimecki, and seven others, when his plane, a Liberator II, serial AL523, crashed into the sea 16 seconds after takeoff from Gibraltar Airport at

23:07 hours. Only the pilot Eduard Prchal (1911-84) survived the crash.

Sikorski was subsequently buried in a brick-lined grave at the Polish

War Cemetery in Newark-on-Trent, England. On September 17, 1993, his remains were exhumed and transferred to the royal crypts at Wawel Castle in Kraków, Poland. Other than to confirm the identity of the remains, no forensic examination was made. On July 2, 2008 Cardinal Stanisław Dziwisz gave consent for the exhumation of

Sikorski's remains from their grave in Krakow. An exhumation was

necessary to investigate the circumstances of how Sikorski died, in

spite of the account provided by the British Government. In January 2009 Polish investigators concluded that there was no evidence Sikorski was murdered. General

Sikorski's death marked a turning point for Polish influence amongst

the Anglo-American allies. No Pole after him would have much sway with

the Allied politicians. Sikorski had been the most prestigious leader of the Polish exiles and his death was a severe setback for the Polish cause. In some ways it was also convenient for the western Allies, who were finding the Polish question a stumbling-block to preserving good relations with Stalin. After

the Soviets had broken off diplomatic relations with Sikorski's

government in April 1943, in May and June Stalin had recalled several

Soviet ambassadors for "consultations": Maxim Litvinov from Washington, Gusev from Montreal, Ivan Maisky from London. In June, Stalin had also initiated secret negotiations with Germany (via the Bulgarian embassy

in Moscow), which had led the western Allies to speculate about the

possibility of the Soviets making a separate peace with Germany. While

Churchill had been publicly supportive of Sikorski's government,

reminding Stalin of his pact with Nazi Germany in 1939 and their joint attack on Poland,

in secret consultations with Roosevelt he admitted that some

concessions would have to be made by Poland to appease the powerful

Soviets. The Polish-Soviet crisis was beginning to threaten cooperation

between the western Allies and the Soviet Union at a time when the

Poles' importance to the western Allies, essential in the first years

of the war, was beginning to fade with the entry into the conflict of

the military and industrial giants, the Soviet Union and the United

States. The Allies had no intention of allowing Sikorski's successor, Stanisław Mikołajczyk, to threaten the alliance with the Soviets. Poland was not represented at the Tehran, Yalta or Potsdam conferences. Only

four months after Sikorski's death, in November 1943, at Tehran,

Churchill and Roosevelt agreed with Stalin that the whole of Poland

east of the "Curzon Line" would be ceded to the Soviets, even if it

were contrary to the Atlantic Charter. In the summer of 1944, as the Polish Government in London had warned all along, the Soviet Government sponsored a Committee of National Liberation in Poland, which the Red Army was

now "liberating." The Committee was recognized by the Soviet Government

as the only legitimate authority in Poland, while Mikołajczyk’s

Government in London, was termed by the Soviets an "illegal and

self-styled authority." At the Potsdam conference in 1945, Churchill

and Stalin settled the details of a new Polish Provisional Government

in which the London Polish government-in-exile would have only minor

influence, further diminished by the Red Army's support for the Polish communists. In the People's Republic of Poland, Sikorski's historic role, like that of all the adherents of the London government, would be minimized and distorted by propaganda,

and those loyal to the government-in-exile would be liable to

imprisonment and even execution. Memory of General Sikorski was

preserved both in Poland and abroad, by organizations like the Sikorski Institute. The Polish government-in-exile would continue in existence until the end of communist rule in Poland in 1990, when Lech Wałęsa became the first post-communist President of Poland (some argue Gen. W. Jaruzelski was the first post-communist President). In 2003, the Polish parliament (Sejm) declared the year (60th anniversary of Sikorski's death) to be the "Year of General Sikorski". He is commemorated in London's Portland Place with a larger than life statue.