<Back to Index>

- Physicist Yves André Rocard, 1903

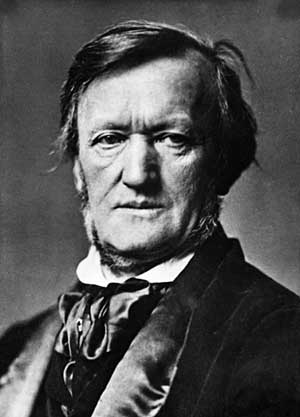

- Composer Wilhelm Richard Wagner, 1813

- Politician Giacomo Matteotti, 1885

Wilhelm Richard Wagner (22 May 1813 – 13 February 1883) was a German composer, conductor, theatre director and essayist, primarily known for his operas (or "music dramas", as they were later called). Unlike most other opera composers, Wagner wrote both the music and libretto for every one of his works.

Wagner's compositions, particularly those of his later period, are notable for contrapuntal texture, rich chromaticism, harmonies and orchestration, and elaborate use of leitmotifs:

musical themes associated with particular characters, locales or plot

elements. Wagner pioneered advances in musical language, such as

extreme chromaticism and quickly shifting tonal centres, which greatly

influenced the development of European classical music. He transformed musical thought through his idea of Gesamtkunstwerk ("total

artwork"), the synthesis of all the poetic, visual, musical and

dramatic arts, epitomized by his monumental four-opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen (1876). To try to stage these works as he imagined them, Wagner built his own opera house, the Bayreuth Festspielhaus. Wilhelm Richard Wagner was born at No. 3 ('The House of the Red and White Lions'), the Brühl, in Leipzig on 22 May 1813, the ninth child of Carl Friedrich Wagner, who was a clerk in the Leipzig police service. Wagner's father died of typhus six

months after Richard's birth, following which Wagner's mother, Johanna

Rosine Wagner, began living with the actor and playwright Ludwig Geyer,

who had been a friend of Richard's father. In August 1814 Johanna

Rosine married Geyer, and moved with her family to his residence in Dresden. For the first 14 years of his life, Wagner was known as Wilhelm Richard Geyer.

Wagner may later have suspected that Geyer was his biological father,

and furthermore speculated incorrectly that Geyer was Jewish. Geyer's

love of the theatre was shared by his stepson, and Wagner took part in

his performances. In his autobiography, Wagner recalled once playing

the part of an angel. The boy Wagner was also hugely impressed by the

Gothic elements of Weber's Der Freischütz.

In late 1820, Wagner was enrolled at Pastor Wetzel's school at

Possendorf, near Dresden, where he received some piano instruction from

his Latin teacher. He could not manage a proper scale but preferred

playing theatre overtures by ear. Geyer died in 1821, when Richard was

eight. Consequently, Wagner was sent to the Kreuz Grammar School in

Dresden, paid for by Geyer's brother. The young Wagner entertained

ambitions as a playwright, his first creative effort (listed as 'WWV 1') being a tragedy, Leubald begun at school in 1826, which was strongly influenced by Shakespeare and Goethe. Wagner was determined to set it to music; he persuaded his family to allow him music lessons. By

1827, the family had moved back to Leipzig. Wagner's first lessons in

composition were taken in 1828–1831 with Christian Gottlieb

Müller. In January 1828 he first heard Beethoven's 7th Symphony and then, in March, Beethoven's 9th Symphony performed in the Gewandhaus. Beethoven became his inspiration, and Wagner wrote a piano transcription of the 9th Symphony, piano sonatas and orchestral overtures. In 1829 he saw the dramatic soprano Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient on

stage, and she became his ideal of the fusion of drama and music in

opera. In his autobiography, Wagner wrote, "If I look back on my life

as a whole, I can find no event that produced so profound an impression

upon me." Wagner claimed to have seen Schröder-Devrient in the

title role of Fidelio; however, it seems more likely that he saw her performance as Romeo in Bellini's I Capuleti e i Montecchi. He enrolled at the University of Leipzig in 1831 where he became a member of the Studentenverbindung Corps Saxonia Leipzig. He also took composition lessons with the cantor of Saint Thomas church, Christian Theodor Weinlig.

Weinlig was so impressed with Wagner's musical ability that he refused

any payment for his lessons, and arranged for one of Wagner's piano

works to be published. A year later, Wagner composed his Symphony in C major, a Beethovenesque work which gave him his first opportunity as a conductor in 1832. He then began to work on an opera, Die Hochzeit (The Wedding), which he never completed. In 1833, Wagner's older brother Karl Albert managed to obtain Richard a position as choir master in Würzburg. In the same year, at the age of 20, Wagner composed his first complete opera, Die Feen (The Fairies). This opera, which clearly imitated the style of Carl Maria von Weber, would go unproduced until half a century later, when it was premiered in Munich shortly after the composer's death in 1883. Meanwhile, Wagner held brief appointments as musical director at opera houses in Magdeburg and Königsberg, during which he wrote Das Liebesverbot (The Ban on Love), based on Shakespeare's Measure for Measure. This second opera was staged at Magdeburg in

1836, but closed before the second performance, leaving the composer

(not for the last time) in serious financial difficulties. On 24 November 1836, Wagner married the actress Christine Wilhelmine "Minna" Planer. In June 1837 they moved to the city of Riga, then in the Russian Empire,

where Wagner became music director of the local opera. A few weeks

afterwards, Minna ran off with an army officer who then abandoned her,

penniless. Wagner took Minna back; however, this was but the first

debacle of a troubled marriage that would end in misery three decades

later. By

1839, the couple had amassed such large debts that they fled Riga to

escape from creditors (debt would plague Wagner for most of his life).

During their flight, they and their Newfoundland dog, Robber, took a stormy sea passage to London, from which Wagner draw the inspiration for The Flying Dutchman (which was based on a sketch by Heinrich Heine). The Wagners spent 1839 to 1842 in Paris, where Richard made a scant living writing articles and arranging operas by other composers, largely on behalf of the Schlesinger publishing house. He also completed Rienzi and The Flying Dutchman during this time. Wagner completed writing his third opera, Rienzi, in 1840. Largely through the agency of Giacomo Meyerbeer, it was accepted for performance by the Dresden Court Theatre (Hofoper) in the German state of Saxony. Thus in 1842, the couple moved to Dresden, where Rienzi was

staged to considerable acclaim. Wagner lived in Dresden for the next

six years, eventually being appointed the Royal Saxon Court Conductor.

During this period, he staged The Flying Dutchman and Tannhäuser, the first two of his three middle-period operas. The Wagners' stay at Dresden was brought to an end by Richard's involvement in leftist politics. A nationalist movement was gaining force in the independent German States,

calling for constitutional freedoms and the unification of the weak

princely states into a single nation. Richard Wagner played an

enthusiastic role in this movement, receiving guests at his house who

included his colleague August Röckel, who was editing the radical

left-wing paper Volksblätter, and the Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin. Widespread discontent against the Saxon government came to a head in April 1849, when King Frederick Augustus II of Saxony dissolved Parliament and rejected a new constitution pressed upon him by the people. The May Uprising broke out, in which Wagner played a minor supporting role. The incipient revolution was quickly crushed by an allied force of Saxon and Prussian troops, and warrants were issued for the arrest of the revolutionaries. Wagner had to flee, first to Paris and then to Zürich. Röckel and Bakunin failed to escape and endured long terms of imprisonment. Wagner spent the next twelve years in exile. He had completed Lohengrin before the Dresden uprising, and now wrote desperately to his friend Franz Liszt to have it staged in his absence. Liszt, who proved to be a friend indeed, eventually conducted the premiere in Weimar in August 1850. Nevertheless,

Wagner found himself in grim personal straits, isolated from the German

musical world and without any income to speak of. Before leaving

Dresden, he had drafted a scenario that would eventually become his

mammoth cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen. He initially wrote the libretto for a single opera, Siegfrieds Tod (Siegfried's Death)

in 1848. After arriving in Zürich he expanded the story to include

an opera about the young Siegfried. He completed the cycle by writing

the libretti for Die Walküre and Das Rheingold and

revising the other libretti to agree with his new concept. Meanwhile,

his wife Minna, who had disliked the operas he had written after Rienzi, was falling into a deepening depression. Finally, he himself fell victim to erysipelas,

which made it difficult for him to continue writing. Wagner's primary

published output during his first years in Zürich was a set of

notable essays: The Art-Work of the Future (1849), in which he described a vision of opera as Gesamtkunstwerk, or "total artwork", in which the various arts such as music, song, dance, poetry, visual arts, and stagecraft were unified; Judaism in Music (1850), a tract directed against Jewish composers; and Opera and Drama (1851), which described ideas in aesthetics that he was putting to use on the Ring operas. By 1852 Wagner had completed the libretto of the four Ring operas, and he began composing Das Rheingold in November 1853, following it immediately with Die Walküre in 1854. He then began work on the third opera, Siegfried in 1856, but finished only the first two acts before deciding to put the work aside to concentrate on a new idea: Tristan und Isolde. Wagner had two independent sources of inspiration for Tristan und Isolde. The first came to him in 1854, when his poet friend Georg Herwegh introduced him to the works of the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer.

Wagner would later call this the most important event of his life. His

personal circumstances certainly made him an easy convert to what he

understood to be Schopenhauer's philosophy, a deeply pessimistic view

of the human condition. He would remain an adherent of Schopenhauer for

the rest of his life, even after his fortunes improved. One

of Schopenhauer's doctrines was that music held a supreme role amongst

the arts. He claimed that music is the direct expression of the world's

essence, which is blind, impulsive will. Wagner quickly embraced this

claim, which must have resonated strongly despite its direct

contradiction with his own arguments, in Opera and Drama, that

music in opera had to be subservient to the cause of drama. Wagner

scholars have since argued that this Schopenhauerian influence caused

Wagner to assign a more commanding role to music in his later operas,

including the latter half of the Ring cycle,

which he had yet to compose. Many aspects of Schopenhauerian doctrine

undoubtedly found their way into Wagner's subsequent libretti. For

example, the self-renouncing cobbler-poet Hans Sachs in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg,

generally considered Wagner's most sympathetic character, is a

quintessentially Schopenhauerian creation (despite being based on a

real person). Schopenhauer asserted that goodness and salvation result

from renunciation of the world and turning against and denying one's

own will. Wagner's second source of inspiration was the poet-writer Mathilde Wesendonck,

the wife of the silk merchant Otto Wesendonck. Wagner met the

Wesendoncks in Zürich in 1852. Otto, a fan of Wagner's music,

placed a cottage on his estate at Wagner's disposal. By 1857, Wagner

had become infatuated with Mathilde. Though

Mathilde seems to have returned some of his affections, she had no

intention of jeopardising her marriage, and kept her husband informed

of her contacts with Wagner. Nevertheless, the affair inspired Wagner to put aside his work on the Ring cycle (which would not be resumed for the next twelve years) and began work onTristan und Isolde, based on the Arthurian love story Tristan and Iseult. The

uneasy affair collapsed in 1858, when Minna intercepted a letter from

Wagner to Mathilde. After the resulting confrontation, Wagner left

Zürich alone, bound for Venice. The following year, he once again moved to Paris to oversee production of a new revision of Tannhäuser, staged thanks to the efforts of Princess Pauline von Metternich. The premiere of the Paris Tannhäuser in 1861 was an utter fiasco, due to disturbances caused by members of the Jockey Club.

Further performances were cancelled, and Wagner hurriedly left the

city. In 1861, the political ban against Wagner in Germany was lifted,

and the composer settled in Biebrich, Prussia, where he began work on Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Despite the failure of Tannhäuser in Paris, the possibility that Der Ring des Nibelungen would

never be finished and Wagner's unhappy personal life, this opera is by

far his sunniest work. Wagner's second wife Cosima would later write,

"when future generations seek refreshment in this unique work, may they

spare a thought for the tears from which the smiles arose." In 1862,

Wagner finally parted with Minna, though he (or at least his creditors)

continued to support her financially until her death in 1866. Between 1861 and 1864 Wagner tried to have Tristan und Isolde produced in Vienna.

Despite over 70 rehearsals the opera remained unperformed, and gained a

reputation as being "unplayable", which further added to Wagner's

financial woes. Wagner's fortunes took a dramatic upturn in 1864, when King Ludwig II assumed the throne of Bavaria at the age of 18. The young king, an ardent admirer of Wagner's operas since childhood, had the composer brought to Munich. He settled Wagner's considerable debts, and made plans to have his new operas produced. Wagner also began to dictate his autobiography, Mein Leben, at the King's request. After grave difficulties in rehearsal, Tristan und Isolde premiered at the National Theatre in Munich on 10 June 1865, the first Wagner premiere in almost 15 years. The conductor of this premiere was Hans von Bülow, whose wife Cosima had

given birth in April that year to a daughter, named Isolde, the child

not of von Bülow but of Wagner. Cosima was 24 years younger than

Wagner and was herself illegitimate, the daughter of the Countess Marie d'Agoult who had left her husband for Franz Liszt.

Liszt disapproved of his daughter seeing Wagner, though the two men

were friends. The indiscreet affair scandalized Munich, and to make

matters worse, Wagner fell into disfavour amongst members of the court,

who were suspicious of his influence on the king. In December 1865,

Ludwig was finally forced to ask the composer to leave Munich. He

apparently also toyed with the idea of abdicating in order to follow

his hero into exile, but Wagner quickly dissuaded him. Ludwig installed Wagner at the villa Tribschen, beside Switzerland's Lake Lucerne. Die Meistersinger was

completed at Tribschen in 1867, and premièred in Munich on 21

June the following year. In October, Cosima finally convinced Hans von

Bülow to grant her a divorce, but not before having two more

children with Wagner, another daughter, named Eva, after the heroine of Meistersinger and a son Siegfried, named for the hero of the Ring.

Minna Wagner had died the previous year and so Richard and Cosima were

now able to marry. The wedding took place on 25 August 1870. On

Christmas Day of that year, Wagner presented the Siegfried Idyll for Cosima's birthday. The marriage to Cosima lasted to the end of Wagner's life. Wagner, settled into his newfound domesticity, turned his energies toward completing the Ring cycle. At Ludwig's insistence, "special previews" of the first two works of the cycle, Das Rheingold and Die Walküre, were performed at Munich, but Wagner wanted the complete cycle to be performed in a new, specially-designed opera house. In 1871, he decided on the small town of Bayreuth as the location of his new opera house. The Wagners moved there the following year, and the foundation stone for the Bayreuth Festspielhaus ("Festival Theatre") was laid. In order to raise funds for the construction, "Wagner Societies"

were formed in several cities, and Wagner himself began touring Germany

conducting concerts. However, sufficient funds were raised only after

King Ludwig stepped in with another large grant in 1874. Later that

year, the Wagners moved into their permanent home at Bayreuth, a villa

that Richard dubbed Wahnfried ("Peace/freedom from delusion/madness", in German). The Festspielhaus finally opened in August 1876 with the premiere of the Ring cycle and has continued to be the site of the Bayreuth Festival ever since. Following the first Bayreuth festival Wagner spent a great deal of time in Italy where he began work on Parsifal,

his final opera. The composition took four years, during which he also

wrote a series of increasingly reactionary essays on religion and art. Wagner completed Parsifal in

January 1882, and a second Bayreuth Festival was held for the new

opera. Wagner was by this time extremely ill, having suffered through a

series of increasingly severe angina attacks. During the sixteenth and final performance of Parsifal on 29 August, he secretly entered the pit during Act III, took the baton from conductor Hermann Levi, and led the performance to its conclusion. After the Festival, the Wagner family journeyed to Venice for the winter. On 13 February 1883, Richard Wagner died of a heart attack at Ca' Vendramin Calergi, a 16th century palazzo on the Grand Canal.

His body was returned to Bayreuth and buried in the garden of the Villa

Wahnfried. Franz Liszt's memorable piece for pianoforte solo, La lugubre gondola, evokes the passing of a black-shrouded funerary gondola bearing Richard Wagner's remains over the Grand Canal.