<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Oswald Arnold Gottfried Spengler, 1880

- Author Gilbert Keith Chesterton, 1874

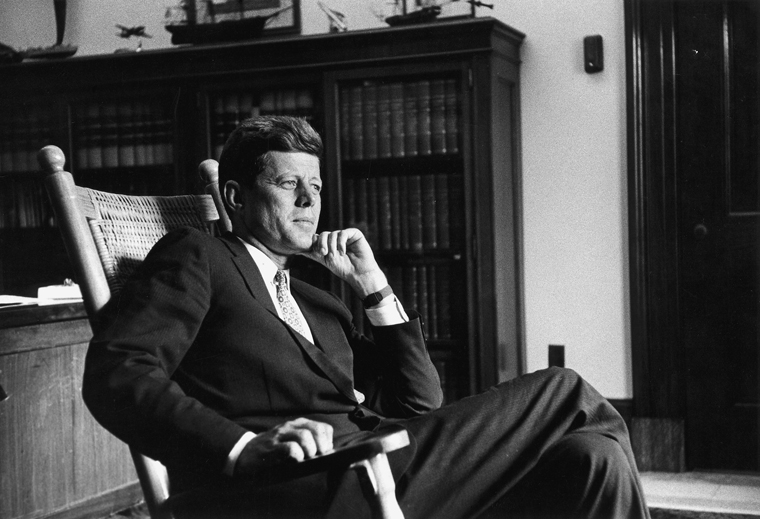

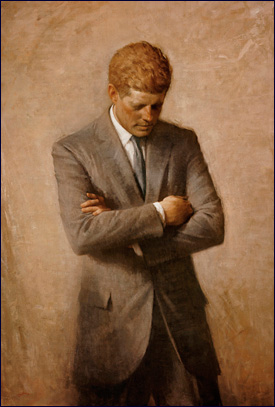

- 35th President of the United States John Fitzgerald "Jack" Kennedy, 1917

John Fitzgerald "Jack" Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK, was the 35th President of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963.

After Kennedy's military service as commander of the Motor Torpedo Boat PT-109 during World War II in the South Pacific, his aspirations turned political. With the encouragement and grooming of his father, Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr., Kennedy represented Massachusetts's 11th congressional district in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1947 to 1953 as a Democrat, and served in the U.S. Senate from 1953 until 1960. Kennedy defeated then Vice President and Republican candidate Richard Nixon in the 1960 U.S. presidential election, one of the closest in American history. He was the second-youngest President (after Theodore Roosevelt), the first President born in the 20th century, and the youngest elected to the office, at the age of 43. Kennedy is the first and only Catholic and the first Irish American president, and is the only president to have won a Pulitzer Prize. Events during his administration include the Bay of Pigs Invasion, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the building of the Berlin Wall, the Space Race, the African American Civil Rights Movement and early stages of the Vietnam War. Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, in Dallas, Texas. Lee Harvey Oswald was charged with the crime but was shot and killed two days later by Jack Ruby before he could be put on trial. The FBI, the Warren Commission, and the House Select Committee on Assassinations concluded that Oswald was the assassin, with the HSCA allowing for the probability of conspiracy based on disputed acoustic evidence. The event proved to be an important moment in U.S. history because of its impact on the nation and the ensuing political repercussions. Today, Kennedy continues to rank highly in public opinion ratings of former U.S. presidents. Kennedy was born at 83 Beals Street in Brookline, Massachusetts on Tuesday, May 29, 1917, at 3:00 p.m., the second son of Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr., and Rose Fitzgerald; Rose, in turn, was the eldest child of John "Honey Fitz" Fitzgerald, a prominent Boston political figure who was the city's mayor and a three-term member of Congress. Kennedy lived in Brookline for his first ten years of life. He attended Brookline's public Edward Devotion School from kindergarten through the beginning of 3rd grade, then Noble and Greenough Lower School and its successor, the Dexter School, a private school for boys, through 4th grade. In September 1927, Kennedy moved with his family to a rented 20-room mansion in Riverdale, Bronx, New York City, then two years later moved five miles (8 km) northeast to a 21-room mansion on a six-acre estate in Bronxville, New York,

purchased in May 1929. He was a member of Scout Troop 2 at Bronxville

from 1929 to 1931 and was to be the first Boy Scout to become President. Kennedy spent summers with his family at their home in Hyannisport, Massachusetts, also purchased in 1929, and Christmas and Easter holidays with his family at their winter home in Palm Beach, Florida, purchased in 1933. In his primary school years, he attended Riverdale Country School,

a private school for boys in Riverdale, for 5th through 7th grade. For

8th grade in September 1930, the 13-year old Kennedy was sent fifty

miles away to Canterbury School, a lay Roman Catholic boarding school for boys in New Milford, Connecticut. In late April 1931, he had appendicitis requiring an appendectomy, after which he withdrew from Canterbury and recuperated at home. In September 1931, Kennedy was sent to The Choate School (now Choate Rosemary Hall), an elite boys boarding school in Wallingford, Connecticut, for his 9th through 12th grade years. His older brother Joe Jr.,

was already at Choate, two years ahead of him, a football star and

leading student in the school. Jack thus spent his first years at

Choate in his brother's shadow. He reacted with rebellious behavior

that attracted a coterie. Their most notorious stunt was to explode a

toilet seat with a powerful firecracker. In the ensuing chapel assembly

the autocratic headmaster, George St. John, brandished the toilet seat

and spoke of certain "muckers" who would "spit in our sea." The defiant

Jack Kennedy took the cue and named his group "The Muckers Club."

Kennedy remained close friends to the end of his life with several of

his Choate fellows, including especially Kirk LeMoyne "Lem" Billings.

Throughout his years at Choate, Kennedy was beset by health problems,

culminating in 1934 with his emergency hospitalization at Yale-New Haven Hospital from January until March. In June 1934 he was admitted to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and diagnosed with colitis. When Kennedy graduated from Choate in June 1935 his superlative in The Brief, the school yearbook (of which he had been business manager), was "Most likely to Succeed." In September 1935, he sailed on the SS Normandie on his first trip abroad with his parents and his sister Kathleen to London with the intent of studying for a year with Professor Harold Laski at the London School of Economics (LSE)

as his elder brother Joe had done. Mystery surrounds his time at LSE

and there is uncertainty about how long he spent there before returning

to America. In October 1935, Kennedy enrolled late and spent six weeks

at Princeton University. He was then hospitalized for two months' observation for possible leukemia at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in

Boston in January and February 1936. He recuperated at the Kennedy

winter home in Palm Beach in March and April, spent May and June

working as a ranch hand on a 40,000-acre (160 km²) cattle ranch outside Benson, Arizona, and in July and August raced sailboats at the Kennedy summer home in Hyannisport. In September 1936 he enrolled as a freshman at Harvard College,

where he produced that year's annual Freshman Smoker, called by a

reviewer "an elaborate entertainment, which included in its cast

outstanding personalities of the radio, screen and sports world." He tried out for the football, golf, and swimming teams. He earned a spot on the varsity swim team. He resided in Winthrop House during

his sophomore through senior years, again following two years behind

his elder brother, Joe. In early July 1937, Kennedy took his convertible, sailed on the SS Washington to

France, and spent ten weeks driving with a friend through France,

Italy, Germany, Holland, and England. In late June 1938, Kennedy sailed

with his father and his brother Joe on the SS Normandie to spend July working with his father, recently appointed U.S. Ambassador to the Court of St. James's by President Roosevelt, at the American embassy in London, and August with his family at a villa near Cannes. From February through September 1939, Kennedy toured Europe, the Soviet Union, the Balkans,

and the Middle East to gather background information for his Harvard

senior honors thesis. He spent the last ten days of August in Czechoslovakia and Germany before returning to London on September 1, 1939, the day Germany invaded Poland. On September 3, 1939, Kennedy and his family were in attendance at the Strangers Gallery of the House of Commons to

hear speeches in support of the United Kingdom's declaration of war on

Germany. Kennedy was sent as his father's representative to help with

arrangements for American survivors of the SS Athenia, before flying back to the U.S. on Pan Am's Dixie Clipper from Foynes, Ireland to Port Washington, New York on his first transatlantic flight at the end of September. In 1940, Kennedy completed his thesis, "Appeasement in Munich," about British participation in the Munich Agreement. He initially intended his thesis to be private, but his father encouraged him to publish it as a book. He graduated cum laude from Harvard with a degree in international affairs in June 1940, and his thesis was published in July 1940 as a book entitled Why England Slept, and became a bestseller. From September to December 1940, Kennedy was enrolled and audited classes at the Stanford Graduate School of Business.

In early 1941, he helped his father complete the writing of a memoir of

his three years as an American ambassador. In May and June 1941,

Kennedy traveled throughout South America.

In the spring of 1941, Kennedy volunteered for the U.S. Army, but was rejected, mainly because of his troublesome back. Nevertheless, in September of that year, the U.S. Navy accepted him, because of the influence of the director of the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI), a former naval attaché to Joseph Kennedy. As an ensign, Kennedy served in the office which supplied bulletins and briefing information for the Secretary of the Navy. It was during this assignment that the attack on Pearl Harbor occurred. He attended the Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps and Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron Training Center before being assigned for duty in Panama and eventually the Pacific theater. He participated in various commands in the Pacific theater and earned the rank of lieutenant, commanding a patrol torpedo (PT) boat. On August 2, 1943, Kennedy's boat, the PT-109, was taking part in a nighttime patrol near New Georgia in the Solomon Islands when it was rammed by the Japanese destroyer Amagiri. Kennedy was thrown across the deck, injuring his already troubled back. Nonetheless, Kennedy gathered his men together and swam, towing a badly-burned crewman by using a life jacketstrap he clenched in his teeth. He towed the wounded man to an island and later to a second island from where his crew was subsequently rescued. For these actions, Kennedy received the Navy and Marine Corps Medal. In October 1943, Kennedy took command of Motor Torpedo Boat PT-59 which was converted from a torpedo boat to a gunboat. On the night of November 2, 1943, the PT-59 and PT-236 took part in the rescue of ambushed Marines on Choiseul Island. Later,

Kennedy was honorably discharged in early 1945, just a few months

before Japan surrendered. Kennedy's other decorations in World War II

included the Purple Heart, American Defense Service Medal, American Campaign Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with two bronze service stars, and the World War II Victory Medal. The incident of the PT-109 was

popularized when he became president and would be the subject of

several magazine articles, books, comic books, TV specials, and a

feature length movie, making the PT-109 one of the most famous U.S. Navy ships of the war. Scale models and even a G.I. Joe figure

based on the incident were still being produced in the 2000s. The

coconut which was used to scrawl a rescue message given to Solomon Islander scouts who found him was kept on his presidential desk and is still at the John F. Kennedy Library. During

his presidency, Kennedy privately admitted to friends that he didn't

feel that he deserved the medals he had received, because the PT-109 incident

had been the result of a botched military operation that had cost the

lives of two members of his crew. When later asked by a reporter how he

became a war hero, Kennedy (known for a sense of humor) joked: "It was

involuntary. They sank my boat." In May 2002, a National Geographic expedition led by Robert Ballard, found what is believed to be the wreckage of the PT-109 in the Solomon Islands. After

World War II, Kennedy had considered the option of becoming a

journalist before deciding to run for political office. Prior to the

war, he had not strongly considered becoming a politician as a career,

because his family, especially his father, had already pinned its

political hopes on his elder brother. Joseph, however, was killed in

World War II, giving John seniority. When in 1946 U.S. Representative James Michael Curley vacated

his seat in an overwhelmingly Democratic district to become mayor of

Boston, Kennedy ran for the seat, beating his Republican opponent by a

large margin. He was a congressman for six years but had a mixed voting

record, often diverging from President Harry S. Truman and the rest of the Democratic Party. In 1952, he defeated incumbent Republican Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. for the U.S. Senate. Kennedy married Jacqueline Lee Bouvier on September 12, 1953. Charles L. Bartlett, a journalist, introduced the pair at a dinner party. Kennedy

underwent several spinal operations over the following two years,

nearly dying (in all he received the Roman Catholic Church's last rites four times during his life) and was often absent from the Senate. During his convalescence in 1956, he published Profiles in Courage,

a book describing eight instances in which U.S. Senators risked their

careers by standing by their personal beliefs. The book was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Biography in 1957. From the time of publication, there have been rumors that this work was actually coauthored by his close adviser Ted Sorensen, who had joined his Senate office staff in 1953 and would serve as a speechwriter for Kennedy until his death. In May 2008, Sorensen confirmed these rumors in his autobiography. In the 1956 presidential election, presidential nominee Adlai Stevenson left the choice of a Vice Presidential nominee to the Democratic convention, and Kennedy finished second in that balloting to Senator Estes Kefauver of

Tennessee. Despite this defeat, Kennedy received national exposure from

that episode that would prove valuable in subsequent years. The Civil Rights Act of 1957 was put forward by President Eisenhower but he "conceded" there were aspects of it he didn't understand. This led Southern senators to "emasculate" his bill. Kennedy voted against letting the bill bypass the Senate Judiciary Committee, which was led by Senator James Eastland,

a segregationist from Mississippi. Kennedy argued procedure should be

followed and the bill could be voted on in the full Senate after a

motion to discharge by the committee, but his vote was seen by some as appeasement of Southern opponents. Kennedy

voted for Title III of the proposed act, which would have given the

Attorney General injunctive powers, but Lyndon Johnson agreed to let

the provision die as a compromise measure. After

consulting two Harvard legal scholars, Kennedy voted for Title IV, the

"Jury Trial Amendment", which in cases of criminal contempt called for

conviction by jury. Many civil rights advocates at the time criticized

the vote as one that would lead to rendering the Act too weak. A compromise final bill which Kennedy supported was passed in September. Staunch segregationists such as senators James Eastland and John McClellan and Mississippi Governor James P. Coleman were early supporters of Kennedy's presidential campaign. In

1958, Kennedy was re-elected to a second term in the United States

Senate, defeating his Republican opponent, Boston lawyer Vincent J.

Celeste, by a wide margin. Senator Joseph McCarthy was a friend of the Kennedy family: Joseph Kennedy, Sr. was a leading McCarthy supporter; Robert F. Kennedy worked for McCarthy's subcommittee, and McCarthy dated Patricia Kennedy.

In 1954, when the Senate was poised to condemn McCarthy, John Kennedy

drafted a speech calling for McCarthy's censure, but never delivered

it. When on December 2, 1954, the Senate rendered its highly publicized

decision to censure McCarthy, Senator Kennedy was in the hospital.

Though absent, Kennedy could have "paired" his vote against that of

another senator, but chose not to; neither did he ever indicate then

nor later how he would have voted. The episode damaged Kennedy's

support in the liberal community, especially with Eleanor Roosevelt, as late as the 1956 and 1960 elections.

On January 2, 1960, Kennedy officially declared his intent to run for President of the United States. In the Democratic primary election, he faced challenges from Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota and Senator Wayne Morse of Oregon. Kennedy defeated Humphrey in Wisconsin and West Virginia and Morse in Maryland and Oregon, although Morse's candidacy is often forgotten by historians. He also defeated token opposition (often write-in candidates) in New Hampshire, Indiana, and Nebraska. In West Virginia, Kennedy visited a coal mine and talked to mine workers to win their support; most people in that conservative, mostly Protestant state

were deeply suspicious of Kennedy's Roman Catholicism. His victory in

West Virginia cemented his credentials as a candidate with broad

popular appeal. At the Democratic Convention, he gave the well-known "New Frontier" speech, which represented the changes America and the rest of the world would be going through. With Humphrey and Morse out of the race, Kennedy's main opponent at the convention in Los Angeles was Senator Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas. Adlai Stevenson,

the Democratic nominee in 1952 and 1956, was not officially running but

had broad grassroots support inside and outside the convention hall.

Senator Stuart Symington of Missouri was also a candidate, as were several favorite sons.

On July 13, 1960, the Democratic convention nominated Kennedy as its

candidate for President. Kennedy asked Johnson to be his Vice

Presidential candidate, despite opposition from many liberal delegates

and Kennedy's own staff, including Robert Kennedy. He needed Johnson's

strength in the South to win what was considered likely to be the closest election since 1916. Major issues included how to get the economy moving again, Kennedy's Roman Catholicism, Cuba, and whether the Soviet space

and missile programs had surpassed those of the U.S. To address fears

that his Roman Catholicism would impact his decision-making, he

famously told the Greater Houston Ministerial Association on September

12, 1960, "I am not the Catholic candidate for President. I am the

Democratic Party candidate for President who also happens to be a

Catholic. I do not speak for my Church on public matters — and the

Church does not speak for me." Kennedy

also brought up the point of whether one-quarter of Americans were

relegated to second-class citizenship just because they were Roman

Catholic. In September and October, Kennedy debated Republican candidate and Vice President Richard Nixon in the first televised U.S. presidential debates in U.S. history. During these programs, Nixon, nursing an injured leg and sporting "five o'clock shadow",

looked tense and uncomfortable, while Kennedy appeared relaxed, leading

the huge television audience to deem Kennedy the winner. Radio

listeners, however, either thought Nixon had won or that the debates

were a draw. Nixon

did not wear make-up during the initial debate, unlike Kennedy. The

debates are now considered a milestone in American political

history—the point at which the medium of television began to play a

dominant role in national politics. After

the first debate Kennedy's campaign gained momentum and he pulled

slightly ahead of Nixon in most polls. On Tuesday, November 8, Kennedy

defeated Nixon in one of the closest presidential elections of the

twentieth century. In the national popular vote Kennedy led Nixon by

just two-tenths of one percent (49.7% to 49.5%), while in the Electoral College he won 303 votes to Nixon's 219 (269 were needed to win). Another 14 electors from Mississippi and Alabama refused to support Kennedy because of his support for the civil rights movement; they voted for Senator Harry F. Byrd, Sr. of Virginia.

John F. Kennedy was sworn in as the 35th President at noon on January 20, 1961. In his inaugural address he

spoke of the need for all Americans to be active citizens, famously

saying, "Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do

for your country." He also asked the nations of the world to join

together to fight what he called the "common enemies of man: tyranny,

poverty, disease, and war itself." In closing, he expanded on his

desire for greater internationalism:

"Finally, whether you are citizens of America or citizens of the world,

ask of us here the same high standards of strength and sacrifice which

we ask of you."

President

Kennedy's foreign policy was dominated by American-Soviet relations.

Much foreign policy revolved around proxy interventions in the context

of the early stage Cold War. John F. Kennedy gave a speech at Saint Anselm College on

May 5, 1960, regarding America's conduct in the new realities of the

emerging Cold War. Kennedy's speech detailed how American foreign

policy should be conducted towards African nations, noting a hint of

support for modern African nationalism by saying that "For we, too,

founded a new nation on revolt from colonial rule".

Prior to Kennedy's election to the presidency, the Eisenhower Administration created a plan to overthrow the Fidel Castro regime in Cuba. Central to such a plan, which was structured and detailed by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) with approval from the US Military but with minimal input from the United States Department of State, was the arming of a counter-revolutionary insurgency composed of anti-Castro Cubans. U.S.-trained Cuban insurgents, led by CIA paramilitary officers from the Special Activities Division, were to invade Cuba and instigate an uprising among the Cuban people in

hopes of removing Castro from power. On April 17, 1961, Kennedy ordered

the previously planned invasion of Cuba to proceed. With support from

the CIA, in what is known as the Bay of Pigs Invasion, 1,500

U.S.-trained Cuban exiles, called "Brigade 2506," returned to the

island in the hope of deposing Castro. However, Kennedy ordered the

invasion to take place without U.S. air support. By April 19, 1961, the

Cuban government had captured or killed the invading exiles, and

Kennedy was forced to negotiate for the release of the 1,189 survivors.

The failure of the plan originated in a lack of dialog among the

military leadership, a result of which was the complete lack of naval

support in the face of organized artillery troops on the island who

easily incapacitated the exile force as it landed on the beach. After

twenty months, Cuba released the captured exiles in exchange for $53

million worth of food and medicine. Furthermore, the incident made

Castro wary of the U.S. and led him to believe that another invasion

would occur. The Cuban Missile Crisis began on October 14, 1962, when American U-2 CIA spy planes took

photographs of a Soviet intermediate-range ballistic missile site under

construction in Cuba. The photos were shown to Kennedy on October 16,

1962. The United States would soon be posed with a serious nuclear

threat. Kennedy faced a dilemma: if the U.S. attacked the sites, it might lead to nuclear war with the U.S.S.R.,

but if the U.S. did nothing, it would endure the threat of nuclear

weapons being launched from close range. Because the weapons were in

such proximity, the U.S. might have been unable to retaliate if they

were launched pre-emptively. Another consideration was that the U.S.

would appear to the world as weak in its own hemisphere. Many

military officials and cabinet members pressed for an air assault on

the missile sites, but Kennedy ordered a naval quarantine in which the

U.S. Navy inspected all ships arriving in Cuba. He began negotiations

with the Soviets and ordered the Soviets to remove all defensive

material that was being built on Cuba. Without doing so, the Soviet and

Cuban peoples would face naval quarantine. A week later, he and Soviet

Premier Nikita Khrushchev reached a basically cordial, lasting

agreement. Khrushchev agreed to remove the missiles subject to U.N.

inspections if the U.S. publicly promised never to invade Cuba and

quietly removed US missiles stationed in Turkey. Following this crisis,

which brought the world closer to nuclear war than at any point before

or since, Kennedy was more cautious in confronting the Soviet Union. Arguing that "those who make peaceful revolution impossible, will make violent revolution inevitable," Kennedy sought to contain communism in Latin America by establishing the Alliance for Progress, which sent foreign aid to troubled countries in the region and sought greater human rights standards in the region. He worked closely with Governor of Puerto Rico Luis Muñoz Marín for the development of the Alliance of Progress, as well as developments in the autonomy of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. As one of his first presidential acts, Kennedy asked Congress to create the Peace Corps. Through this program, Americans volunteer to help underdeveloped nations in areas such as education, farming, health care, and construction. The extent of Kennedy's involvement in Vietnam remained classified until the release of the Pentagon Papers in 1971. In

Southeast Asia, Kennedy followed Eisenhower's lead by using limited

military action as early as 1961 to fight the Communist forces led by Ho Chi Minh.

Proclaiming a fight against the spread of Communism, Kennedy enacted

policies providing political, economic, and military support for the

unstable French-installed South Vietnamese government,

which included sending 16,000 military advisors and U.S. Special Forces

to the area. Kennedy also authorized the use of free-fire zones, napalm, defoliants, and jet planes. U.S.

involvement in the area escalated until Lyndon Johnson, his successor,

directly deployed regular U.S. forces for fighting the Vietnam War. By

July 1963, Kennedy faced a crisis in Vietnam: despite increased U.S.

support, the South Vietnamese military was only marginally effective

against pro-Communist Viet Minh and Viet Cong forces. Regarding Ngo Dinh Diem,

the Roman Catholic President of South Vietnam, as insufficiently

anti-Communist, the U.S. gave secret assurances of non-interference for

an impending coup d'état. On

November 1, 1963, South Vietnamese generals overthrew the Diem

government, arresting and soon killing Diem (though the circumstances

of his death were obfuscated). Kennedy sanctioned Diem's overthrow. One

reason to support the coup was a fear that Diem might negotiate a

neutralist coalition government which included Communists, as had

occurred in Laos in 1962. Dean Rusk, Secretary of State, remarked "This kind of neutralism…is tantamount to surrender." During

his time in office, Kennedy increased the number of U.S. military in

Vietnam from 800 to 16,300. It remains a point of some controversy

among historians whether or not Vietnam would have escalated to the

point it did had Kennedy served out his full term and been re-elected

in 1964. Fueling the debate are statements made by Kennedy and Johnson's Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara that Kennedy was strongly considering pulling out of Vietnam after the 1964 election. In the film "The Fog of War",

not only does McNamara say this, but a tape recording of Lyndon Johnson

confirms that Kennedy was planning to withdraw from Vietnam, a position

Johnson states he strongly disapproved of. Additional

evidence is Kennedy's National Security Action Memorandum (NSAM) 263,

dated October 11, 1963, which ordered withdrawal of 1,000 military

personnel by the end of 1963. Nevertheless,

given the stated reason for the overthrow of the Diem government, such

action would have been a policy reversal, but Kennedy was generally

moving in a less hawkish direction in the Cold War since his acclaimed

speech about World Peace at American University the previous June 10, 1963. According

to historian Lawrence Freedman, regarding Kennedy's statements about

withdrawing from Vietnam, it was, "less of a definite decision than a

working assumption, based on a hope for stability rather than an

expectation of chaos". After

Kennedy's assassination, the new President Lyndon B. Johnson

immediately reversed his predecessor's order to withdraw 1,000 military

personnel by the end of 1963 with his own NSAM 273 on November 26, 1963.

On

June 10, 1963, Kennedy delivered the commencement address at American

University in Washington, D.C., proclaiming that "The United States, as

the world knows, will never start a war. We do not want a war. We do

not now expect a war," but cautioning that, "We shall be prepared if

others wish it. We shall be alert to try to stop it. But we shall also

do our part to build a world of peace where the weak are safe and the

strong are just." Under simultaneous and opposing pressures from the Allies and the Soviets, Germany was divided. The Berlin Wall separated West and East Berlin, the latter being under the control of the Soviets. On June 26, 1963, Kennedy visited West Berlin and gave a public speech criticizing communism. Kennedy used the construction of the Berlin Wallas an example of the failures of communism: "Freedom has many difficulties and democracy is not perfect, but we have never had to put a wall up to keep our people in." The speech is known for its famous phrase "Ich bin ein Berliner". Nearly five-sixths of the population was on the street when Kennedy said the famous phrase. He remarked to aides afterwards: "We'll never have another day like this one."

Troubled by the long-term dangers of radioactive contamination and nuclear weapons proliferation, Kennedy pushed for the adoption of a Limited or Partial Test Ban Treaty,

which prohibited atomic testing on the ground, in the atmosphere, or

underwater, but did not prohibit testing underground. The United

States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union were the initial

signatories to the treaty. Kennedy signed the treaty into law in August

1963.

On the occasion of his visit to the Republic of Ireland in 1963, President Kennedy joined with Irish President Éamon de Valera to

form The American Irish Foundation. The mission of this organization

was to foster connections between Americans of Irish descent and the

country of their ancestry. Kennedy furthered these connections of

cultural solidarity by accepting a grant of armorial bearings from the Chief Herald of Ireland.

Kennedy had near-legendary status in Ireland, due to his ancestral ties

to the country. Irish citizens who were alive in 1963 often have very

strong memories of Kennedy's momentous visit. He also visited the original cottage at Dunganstown, near New Ross,

where previous Kennedys had lived before emigrating to America, and

said: "This is where it all began …" On December 22, 2006, the Irish Department of Justice released

declassified police documents that indicated that Kennedy was the

subject of three death threats during this visit. Though these threats

were determined to be hoaxes, security was heightened. Kennedy ended a period of tight fiscal policies, loosening monetary policy to keep interest rates down and encourage growth of the economy. Kennedy

presided over the first government budget to top the $100 billion mark,

in 1962, and his first budget in 1961 led to the country's first

non-war, non-recession deficit. The

economy, which had been through two recessions in three years and was

in one when Kennedy took office, accelerated notably during his brief

presidency. Despite low inflation and interest rates, GDP had grown by

an average of only 2.2% during the Eisenhower presidency (scarcely more

than population growth at the time), and had declined by 1% during

Eisenhower's last twelve months in office. Stagnation

had taken a toll on the nation's labor market, as well: unemployment

had risen steadily from under 3% in 1953 to 7%, by early 1961.

The

economy turned around and prospered during the Kennedy administration.

GDP expanded by an average of 5.5% from early 1961 to late 1963, while inflation remained steady at around 1% and unemployment began to ease; industrial production rose by 15% and motor vehicle sales leapt by 40%. This

rate of growth in GDP and industry continued until around 1966, and has

yet to be repeated for such a sustained period of time. As President, Kennedy oversaw the last pre-Furman federal execution, and, as of 2008, the last military execution. Governor of Iowa Harold Hughes, a death penalty opponent, personally contacted Kennedy to request clemency for Victor Feguer, who was sentenced to death by a federal court in Iowa, but Kennedy turned down the request and Feguer was executed on March 15, 1963. Kennedy commuted a death sentence imposed by military court on seaman Jimmie Henderson on February 12, 1962, changing the penalty to life in prison. On March 22, 1962, Kennedy signed into law HR5143 (PL87-423), abolishing the mandatory death penalty for first degree murder in the District of Columbia,

the only remaining jurisdiction in the United States with a mandatory

death sentence for first degree murder, replacing it with life

imprisonment with parole if the jury could not decide between life

imprisonment and the death penalty, or if the jury chose life

imprisonment by a unanimous vote. The death penalty in the District of Columbia has not been applied since 1957, and has now been abolished. The turbulent end of state-sanctioned racial discrimination was one of the most pressing domestic issues of Kennedy's era. The United States Supreme Court had ruled in 1954 in Brown v. Board of Education that racial segregation in

public schools was unconstitutional. However, many schools, especially

in southern states, did not obey the Supreme Court's judgment.

Segregation on buses, in restaurants, movie theaters, bathrooms, and

other public places remained. Kennedy supported racial integration and civil rights, and during the 1960 campaign he telephoned Coretta Scott King, wife of the jailed Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr.,

which perhaps drew some additional black support to his candidacy. John

and Robert Kennedy's intervention secured the early release of King

from jail. In September 1962, James Meredith tried to enroll at the University of Mississippi,

but he was prevented from doing so by white students and other

Mississippians. Robert Kennedy, then Attorney General, responded by

sending some 400 U.S. Marshals, while President Kennedy reluctantly sent about 3,000 federal troops after the situation on campus turned violent. Riots at

the campus left two dead and dozens injured. Meredith finally enrolled

in his first class. Kennedy also assigned federal marshals to protect Freedom Riders. As

President, Kennedy initially believed the grass roots movement for

civil rights would only anger many Southern whites and make it even

more difficult to pass civil rights laws through Congress, which was

dominated by conservative Southern Democrats, and he distanced himself

from it. As a result, many civil rights leaders viewed Kennedy as

unsupportive of their efforts. On June 11, 1963, President Kennedy intervened when Alabama Governor George Wallace blocked the doorway to the University of Alabama to stop two African American students, Vivian Malone and James Hood, from enrolling. George Wallace moved aside after being confronted by federal marshals, Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach and the Alabama National Guard. That evening Kennedy gave his famous civil rights address on national television and radio. Kennedy proposed what would become the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Kennedy signed the executive order creating the Presidential Commission on the Status of Women in 1961. Commission

statistics revealed that women were also experiencing discrimination.

Their final report documenting legal and cultural barriers was issued

in October 1963, a month before Kennedy's assassination. In 1963, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, who hated civil-rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. and viewed him as an upstart troublemaker, presented the Kennedy Administration with allegations that some of King's close confidants and advisers were communists. Concerned that the allegations, if made public, would derail the Administration's civil rights initiatives, Robert Kennedy warned

King to discontinue the suspect associations, and later felt compelled

to issue a written directive authorizing the FBI to wiretap King and

other leaders of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, King's civil rights organization. Although Kennedy only gave written approval for limited wiretapping of King's phones "on a trial basis, for a month or so",

Hoover extended the clearance so his men were "unshackled" to look for

evidence in any areas of King's life they deemed worthy. The wire tapping continued through June 1966 and was revealed in 1968. Due to a recession, Kennedy used the power of federal agencies to influence US Steel not to institute a price increase. The Wall Street Journal wrote that the administration had set prices of steel "by naked power, by threats, by agents of the state security police." Yale law professor Charles Reich wrote in The New Republic that the administration had violated civil liberties by calling a grand jury to indict US Steel so quickly.

John F. Kennedy initially proposed an overhaul of American immigration policy that later was to become the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, sponsored by Kennedy's brother Senator Edward Kennedy.

It dramatically shifted the source of immigration from Northern and

Western European countries towards immigration from Latin America and

Asia and shifted the emphasis of selection of immigrants towards

facilitating family reunification. Kennedy

wanted to dismantle the selection of immigrants based on country of

origin and saw this as an extension of his civil rights policies. Kennedy was eager for the United States to lead the way in the space race. Sergei Khrushchev says

Kennedy approached his father, Nikita, twice about a "joint venture" in

space exploration — in June 1961 and autumn 1963. On the first occasion,

the Soviet Union was far ahead of America in terms of space technology.

Kennedy first announced the goal for landing a man on the Moon in speaking to a Joint Session of Congress on May 25, 1961. Kennedy later made a speech at Rice University on

September 12, 1962, in which he said "No nation which expects to be the

leader of other nations can expect to stay behind in this race for

space." and "We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the

other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard." On

the second approach to Khrushchev, the Ukrainian was persuaded that

cost-sharing was beneficial and American space technology was forging

ahead. The U.S. had launched a geostationary satellite and Kennedy had asked Congress to approve more than $25 billion for the Apollo Project.

Construction of the Kinzua Dam flooded 10,000 acres (4,047 ha) of Seneca nation land that they occupied under the Treaty of 1794, and forced approximately 600 Seneca to relocate to the northern shores upstream of the dam at Salamanca, New York.

Kennedy was asked by the American Civil Liberties Union to intervene

and halt the project but he declined citing a critical need for flood

control. He did express concern for the plight of the Seneca, and

directed government agencies to assist in obtaining more land, damages,

and assistance to help mitigate their displacement. President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas, at 12:30 p.m. Central Standard Time on November 22, 1963, while on a political trip to Texas to smooth over factions in the Democratic Party between liberals Ralph Yarborough and Don Yarborough (no relation) and conservative John Connally. He

was shot once in the upper back and was killed with a final shot to the

head. He was pronounced dead at 1:00 p.m. Only 46, President Kennedy

died younger than any U.S. president to date. Lee Harvey Oswald,

an employee of the schoolbook depository from which the shots were

suspected to have been fired, was arrested on charges of the murder of

a local police officer and was subsequently charged with the

assassination of Kennedy. He denied shooting anyone, claiming he was a patsy, but was killed by Jack Ruby on

November 24, before he could be indicted or tried. Ruby was then

arrested and convicted for the murder of Oswald. Ruby successfully

appealed his conviction and death sentence but became ill and died of

cancer while the date for his new trial was being set. President Johnson created the Warren Commission — chaired by Chief Justice Earl Warren — to

investigate the assassination, which concluded that Oswald was the lone

assassin. The results of this investigation are disputed by many. On

November 25, 1963, John F. Kennedy's body was buried in a small plot,

(20 ft. by 30 ft.), in Arlington National Cemetery. Over a

period of 3 years, (1964–1966), an estimated 16 million people had

visited his grave. On March 14, 1967, Kennedy's body was moved to a

permanent burial plot and memorial at Arlington National Cemetery. The funeral was officiated by Father John J. Cavanaugh. The honor guard at JFK`s graveside was the 37th Cadet Class of the Irish Army.

JFK was greatly impressed by the Irish Cadets on his last official

visit to the Republic of Ireland, so much so that Jackie Kennedy

requested the Irish Army to be the honor guard at the funeral. Kennedy's wife, Jacqueline and their two deceased minor children were buried with him later. His brother, Senator Robert Kennedy, was buried nearby in June 1968. In August 2009 his brother, Senator Edward M. Kennedy, was also buried near his two brothers. JFK's grave is lit with an "Eternal Flame." Kennedy and William Howard Taft are the only two U.S. Presidents buried at Arlington.

In 1963, the Kennedy administration backed a coup against the government of Iraq headed by General Abdel Karim Kassem, who five years earlier had deposed the Western-allied Iraqi monarchy. The CIA helped the new Ba'ath Party government led by Abdul Salam Arif in ridding the country of suspected leftists and Communists. In a Baathist bloodbath,

the government used lists of suspected Communists and other leftists

provided by the CIA, to systematically murder untold numbers of Iraq's

educated elite — killings in which Saddam Hussein himself

is said to have participated. The victims included hundreds of doctors,

teachers, technicians, lawyers, and other professionals as well as

military and political figures. According to an op-ed in the New York Times, the U.S. sent arms to the new regime, weapons later used against the same Kurdish insurgents the U.S. supported against Kassem and then abandoned him. American and UK oil and other interests, including Mobil, Bechtel, and British Petroleum, were conducting business in Iraq.

Kennedy called his domestic program the "New Frontier". It ambitiously promised federal funding for education, medical care for

the elderly, economic aid to rural regions, and government intervention

to halt the recession. Kennedy also promised an end to racial discrimination. In 1963, he proposed a tax reform which included income tax cuts,

but this was not passed by Congress until 1964, after his death. Few of

Kennedy's major programs passed Congress during his lifetime, although,

under his successor Johnson, Congress did vote them through in 1964–65.

Khrushchev

agreed to a joint venture in late 1963, but Kennedy was assassinated

before the agreement could be formalized. On July 20, 1969, almost six

years after JFK's death, Project Apollo's goal was finally realized

when men landed on the Moon.