<Back to Index>

- Physician Crawford Williamson Long, 1815

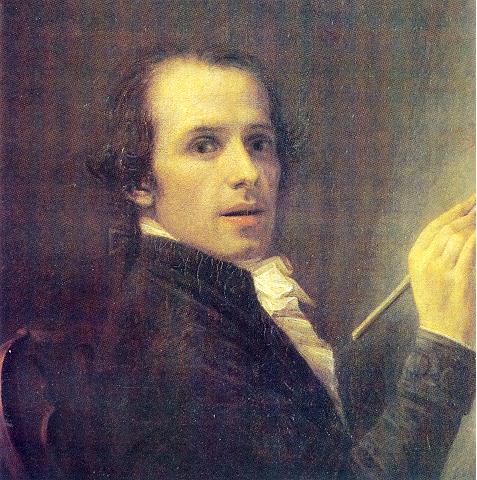

- Sculptor Antonio Canova, 1757

- 1st Minister of Education Ivan Ivanovich Shuvalov, 1727

PAGE SPONSOR

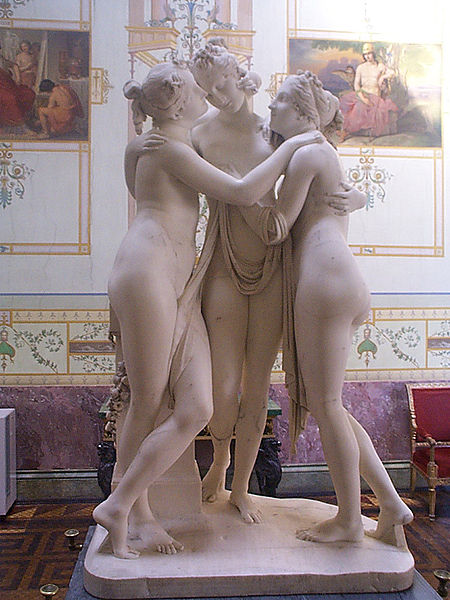

Antonio Canova (1 November 1757 – 13 October 1822) was a Venetian sculptor who became famous for his marble sculptures that delicately rendered nude flesh. The epitome of the neoclassical style, his work marked a return to classical refinement after the theatrical excesses of Baroque sculpture.

Antonio Canova was born in Possagno, a village of the Republic of Venice situated amid the recesses of the hills of Asolo, where these form the last undulations of the Venetian Alps, as they subside into the plains of Treviso. At three years of age Canova was deprived of both parents, his father dying and his mother remarrying. Their loss, however, was compensated by the tender solicitude and care of his paternal grandfather and grandmother, the latter of whom lived to experience in her turn the kindest personal attention from her grandson, who, when he had the means, gave her an asylum in his house at Rome. His father and grandfather followed the occupation of stone-cutters or minor statuaries; and it is said that their family had for several ages supplied Possagno with members of that calling. As soon as Canova's hand could hold a pencil, he was initiated into the principles of drawing by his grandfather Pasino. The latter possessed some knowledge both of drawing and of architecture, designed well, and showed considerable taste in the execution of ornamental works. He was greatly attached to his art; and upon his young charge he looked as one who was to perpetuate, not only the family name, but also the family profession. The early years of Canova were passed in study. The bias of his mind was to sculpture, and the facilities afforded for the gratification of this predilection in the workshop of his grandfather were eagerly improved. In his ninth year he executed two small shrines of Carrara marble, which are still extant. Soon after this period he appears to have been constantly employed under his grandfather. Amongst those who patronized the old man was the patrician family Falier of Venice, and by this means young Canova was first introduced to the senator of that name, who afterwards became his most zealous patron.

Between the younger son, Giuseppe Falier, and the artist a friendship commenced which terminated only with life. The senator Falier was induced to receive him under his immediate protection. It has been related by an Italian writer and since repeated by several biographers, that Canova was indebted to a trivial circumstance - the moulding of a lion in butter - for the warm interest which Falier took in his welfare. The anecdote may or may not be true. By his patron Canova was placed under Bernardi, or, as he is generally called by filiation, Giuseppe Torretto, a sculptor of considerable eminence, who had taken up a temporary residence at Pagnano, one of Asolo's boroughs in the vicinity of the senator's mansion. This took place whilst Canova was in his thirteenth year; and with Torretto he continued about two years, making in many respects considerable progress. This master returned to Venice, where he soon afterwards died; but by the high terms in which he spoke of his pupil to Falier, the latter was induced to bring the young artist to Venice, whither he accordingly went, and was placed under a nephew of Torretto. With this instructor he continued about a year, studying with the utmost assiduity.

After the termination of this engagement he began to work on his own account, and received from his patron an order for a group, Orpheus and Eurydice. The first figure, which represents Eurydice in flames and smoke, in the act of leaving Hades,

was completed towards the close of his sixteenth year. It was highly

esteemed by his patron and friends, and the artist was now considered

qualified to appear before a public tribunal. The

kindness of some monks supplied him with his first workshop, which was

the vacant cell of a monastery. Here for nearly four years he labored

with the greatest perseverance and industry. He was also regular in his

attendance at the academy, where he carried off several prizes. But he

relied far more on the study and imitation of nature. A large portion

of his time was also devoted to anatomy, which science was regarded by

him as the secret of the art. He likewise frequented places of public

amusement, where he carefully studied the expressions and attitudes of

the performers. He formed a resolution, which was faithfully adhered to

for several years, never to close his eyes at night without having

produced some design. Whatever was likely to forward his advancement in

sculpture he studied with ardour. On archaeological pursuits he

bestowed considerable attention. With ancient and modern history he

rendered himself well acquainted and he also began to acquire some of

the continental languages. Three

years had now elapsed without any production coming from his chisel. He

began, however, to complete the group for his patron, and the Orpheus which

followed evinced the great advance he had made. The work was

universally applauded, and laid the foundation of his fame. Several

groups succeeded this performance, amongst which was that of Daedalus and Icarus,

the most celebrated work of his noviciate. The terseness of style and

the faithful imitation of nature which characterized them called forth

the warmest admiration. His merits and reputation being now generally

recognized, his thoughts began to turn from the shores of the Adriatic to the banks of the Tiber, for which he set out at the commencement of his twenty-fourth year. Before

his departure for Rome, his friends had applied to the Venetian senate

for a pension, to enable him to pursue his studies without

embarrassment. The application was ultimately successful. The stipend

amounted to three hundred ducats (about 60 pounds per annum), and was

limited to three years. Canova had obtained letters of introduction to

the Venetian ambassador, the Cavaliere Zulian, and enlightened and

generous protector of the arts, and was received in the most hospitable

manner. His

arrival in Rome, on 28 December 1780, marks a new era in his life. It

was here he was to perfect himself by a study of the most splendid

relics of antiquity, and to put his talents to the severest test by a

competition with the living masters of the art. The result was equal to

the highest hopes cherished either by himself or by his friends. The

work which first established his fame at Rome was Theseus Vanquishing the Minotaur, now in the collections of the Victoria & Albert Museum, in London.

The figures are of the heroic size. The victorious Theseus is

represented as seated on the lifeless body of the monster. The

exhaustion which visibly pervades his whole frame proves the terrible

nature of the conflict in which he has been engaged. Simplicity and

natural expression had hitherto characterized Canova's style; with

these were now united more exalted conceptions of grandeur and of

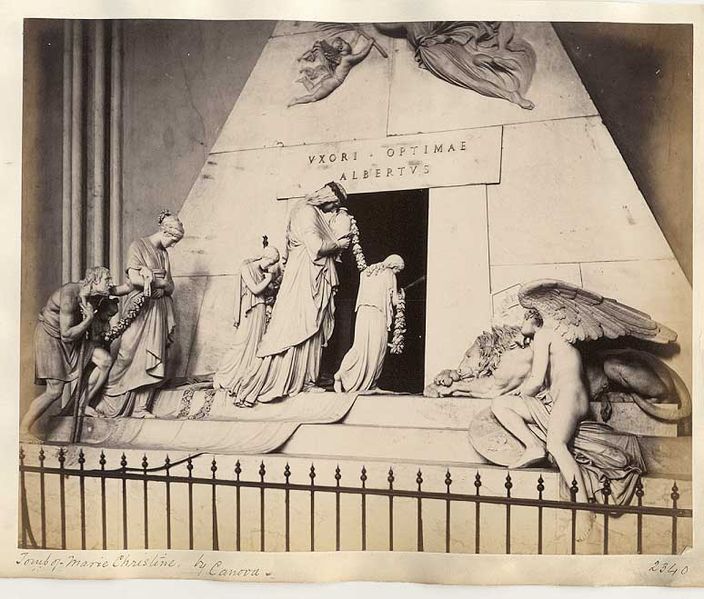

truth. The Theseus was regarded with fervent admiration. Canova's next undertaking was a monument in honor of Clement XIV;

but before he proceeded with it he deemed it necessary to request

permission from the Venetian senate, whose servant he considered

himself to be, in consideration of the pension. This he solicited, in

person, and it was granted. He returned immediately to Rome, and opened

his celebrated studio close to the Via del Babuino. He spent about two

years of unremitting toil in arranging the design and composing the

models for the tomb of the pontiff. After these were completed, other

two years were employed in finishing the monument, and it was finally

opened to public inspection in 1787. The work, in the opinion of

enthusiastic dilettanti, stamped the author as the first artist of modern times. After five years of incessant labor, he completed another cenotaph, to the memory of Clement XIII, which raised his fame still higher. Works now came rapidly from his chisel. Amongst these is Psyche,

with a butterfly, which is placed on the left hand, and held by the

wings with the right. This figure, which is intended as a

personification of man's immaterial part, is considered as in almost

every respect the most faultless and classical of Canova's works. In

two different groups, and with opposite expression, the sculptor has

represented Cupid with

his bride; in the one they are standing, in the other recumbent. These

and other works raised his reputation so high that the most flattering

offers were sent to him from the Russian court to induce him to remove

to St Petersburg, but these were declined, although many of his finest works made their way to the Hermitage Museum.

"Italy", says he, in writing of the occurrence to a friend, "Italy is

my country - is the country and native soil of the arts. I cannot leave

her; my infancy was nurtured here. If my poor talents can be useful in

any other land, they must be of some utility to Italy; and ought not

her claim to be preferred to all others?" Numerous

works were produced in the years 1795-1797, of which several were

repetitions of previous productions. One was the celebrated group

representing the Parting of Venus and Adonis. This famous production was sent to Naples. The French Revolution was

now extending its shocks over Italy; and Canova sought obscurity and

repose in his native Possagno. Thither he retired in 1798, and there he

continued for about a year, principally employed in painting, of which

art also he had some knowledge. Events in the political world having

come to a temporary lull, he returned to Rome; but his health being

impaired from arduous application, he took a journey through a part of Germany,

in company with his friend Prince Rezzonico. He returned from his

travels much improved, and again commenced his labors with vigour and

enthusiasm.

The

events which marked the life of the artist during the first fifteen

years of the period in which he was engaged on the above-mentioned

works scarcely merit notice. His mind was entirely absorbed in the

labors of his studio, and, with the exception of his journeys to Paris, one to Vienna, and a few short intervals of absence in Florence and other parts of Italy, he never quit Rome. In his own words, "his statues were the sole proofs of his civil existence." There

was, however, another proof, which modesty forbade him to mention, an

ever-active benevolence, especially towards artists. In 1815 he was

commissioned by the Pope to superintend the transmission from Paris of

those works of art which had formerly been conveyed thither under the

direction of Napoleon.

By his zeal and exertions - for there were many conflicting interests

to reconcile - he adjusted the affair in a manner at once creditable to

his judgment and fortunate for his country. In the autumn of this year he gratified a wish he had long entertained of visiting London, where he received the highest tokens of esteem. The artist for whom he showed particular sympathy and regard in London was Benjamin Haydon,

who might at the time be counted the sole representative of historical

painting there, and whom he especially honored for his championship of

the Elgin marbles, then recently transported to England, and ignorantly depreciated by polite connoisseurs. Among Canova's English pupils were sculptors Sir Richard Westmacott and John Gibson. Canova

returned to Rome in the beginning of 1816, with the ransomed spoils of

his country's genius. Immediately after, he received several marks of

distinction: he was made President of the Accademia di San Luca, the

main artistic institution in Rome, and by the hand of the Pope himself

his name was inscribed in "the Golden Volume of the Capitol", and he

received the title of Marquis of Ischia, with an annual pension of 3000 crowns. He now contemplated a great work, a colossal statue of Religion.

The model filled Italy with admiration; the marble was procured, and

the chisel of the sculptor ready to be applied to it, when the jealousy

of churchmen as to the site, or some other cause, deprived the country

of the projected work. The mind of Canova was inspired with the warmest

sense of devotion, and though foiled in this instance he resolved to

consecrate a shrine to the cause. In his native village he began to

make preparations for erecting a temple which was to contain, not only

the above statue, but other works of his own; within its precincts were

to repose also the ashes of the founder. Accordingly he repaired to

Possagno in 1819. After the foundation-stone of this edifice had been

laid, Canova returned to Rome; but every succeeding autumn he continued

to visit Possagno, in order to direct the workmen, and encourage them

with pecuniary rewards and medals. In

the meantime the vast expenditure exhausted his resources, and

compelled him to labor with unceasing assiduity notwithstanding age and

disease. During the period which intervened between commencing

operations at Possagno and his decease, he executed or finished some of

his most striking works. Amongst these were the group Mars and Venus, the colossal figure of Pius VI, the Pietà, the St John, the recumbent Magdalen. The last performance which issued from his hand was a colossal bust of his friend, the Count Cicognara. In

May 1822 he paid a visit to Naples, to superintend the construction of

wax moulds for an equestrian statue of the perjured Bourbon king Ferdinand VII.

This journey materially injured his health, but he rallied again on his

return to Rome. Towards the latter end of the year he paid his annual

visit to the place of his birth, when he experienced a relapse. He

proceeded to Venice, and expired there at the age of nearly sixty-five.

His disease was one which had affected him from an early age, caused by

the continual use of carving-tools, producing a depression of the ribs.

The most distinguished funeral honors were paid to his remains, which

were deposited in the temple at Possagno on 25 October 1822. His heart

was interred in a marble pyramid he designed as a mausoleum for the painter Titian in the church of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari in Venice, now a monument to the sculptor.