<Back to Index>

- Explorer and Father of Texas Stephen Fuller Austin, 1793

- Painter Annibale Carracci, 1560

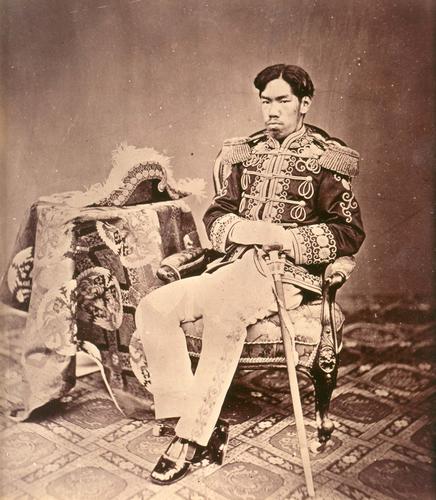

- Meiji Emperor of Japan Mutsuhito, 1852

PAGE SPONSOR

The Meiji Emperor (3 November 1852 - 30 July 1912) or Meiji the Great was the 122nd emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession, reigning from 3 February 1867 until his death. He presided over a time of rapid change in Japan, as the nation rose from a feudal shogunate to become a world power.

His personal name was Mutsuhito, and although outside of Japan he is sometimes called by this name or Emperor Mutsuhito, in Japan emperors are referred to only by their posthumous names. Use of an emperor's personal name would be considered too familiar, or even blasphemous.

At the time of his birth in 1852, Japan was an isolated, pre-industrial, feudal country dominated by the Tokugawa Shogunate and the daimyo, who ruled over the country's more than 250 decentralized domains. By the time of his death in 1912, Japan had undergone a political, social, and industrial revolution at home (Meiji Restoration) and emerged as one of the great powers on the world stage. A detailed account of the State Funeral in the New York Times concluded

with an observation: "The contrast between that which preceded the

funeral car and that which followed it was striking indeed. Before it

went old Japan; after it came new Japan." The Tokugawa Shogunate had been established in the early 17th century. Under its rule, the shogun governed Japan. About 180 lords, known as daimyo, ruled autonomous realms under the shogun, who occasionally called upon the daimyo for gifts, but did not tax them. The daimyo were controlled by the shogun in other ways; only the shogun could approve their marriages, and the shogun could divest a daimyo of his lands. In 1615, the first Tokugawa shogun, Tokugawa Ieyasu, who had officially retired from his position, and his son Tokugawa Hidetada,

the titular shogun, issued a code of behavior for the nobility. Under

it, the emperor was required to devote his time to scholarship and the

arts. The

emperors under the shoganate appear to have closely adhered to this

code, studying Confucian classics and devoting time to poetry and

calligraphy. They were only taught the rudiments of Japanese and Chinese history and geography. The shogun did not seek the consent or advice of the emperor for his actions. Emperors almost never left their palace compound, or Gosho in Kyoto, except after an emperor retired or to take shelter in a temple if the palace caught on fire. Few

emperors lived long enough to retire; of the Emperor Meiji's five

predecessors, only his grandfather lived into his forties, and died

aged forty-six. The imperial family suffered very high rates of infant mortality; all five

of the emperor's brothers and sisters died as infants, and only five of

fifteen of his own children would reach adulthood. Soon after taking control, shoganate officials (known generically as bakufu)

ended much Western trade with Japan, and barred missionaries from the

islands. Only the Dutch continued trade with Japan, maintaining a post

on the island of Dejima by Nagasaki.

However, by the early 19th century, European and American vessels

appeared in the waters around Japan with increasing frequency. The

child who would, after his death, become known as the Emperor Meiji was

born on November 3, 1852 in a small house on his maternal grandfather's

property at the north end of the Gosho.

At the time, a birth was believed to be polluting, and so imperial

princes were not born in the Palace, but usually in a structure, often

temporary, near the pregnant woman's father's house. The boy's mother, Nakayama Yoshiko was a concubine (gon no tenji) to the Emperor Kōmei and the daughter of the acting major counselor, Nakayama Tadayasu. The young prince was given the name Sachinomiya, or Prince Sachi. The young prince was born at a time of change for Japan. This change was symbolized dramatically when Commodore Matthew Perry and his squadron of what were dubbed "the Black Ships" by the Japanese, sailed into the harbor at Edo (today

known as Tokyo) in July 1853. Perry sought to open Japan to trade, and

warned the Japanese of military consequences if they did not agree. During the crisis brought on by Perry's arrival, the bakufu took

the highly unusual step of consulting with the Imperial Court, and the

Emperor Kōmei's officials advised that they felt the Americans should

be allowed to trade and asked that they be informed in advance of any

steps to be taken upon Perry's return. This request was initially

honored by the bakufu, and for the first time in at least 250 years, they consulted with the Imperial Court before making a decision. Feeling that they could not win a war, Japan allowed trade and submitted to what it dubbed the "Unequal Treaties", giving up tariff authority and the right to try foreigners in its own courts. The bakufu willingness to consult with the Court was short-lived: In 1858, word of a treaty arrived

with a letter stating that due to shortness of time, it had not been

possible to consult. The Emperor Kōmei was so incensed that he

threatened to abdicate — though even this action would have required the

consent of the Shogun. Much

of the Emperor Meiji's boyhood is known only through later accounts,

which his biographer, Donald Keene points out are often contradictory.

One contemporary described the young prince as healthy and strong,

somewhat of a bully and exceptionally talented at sumo.

Another states that the prince was delicate and often ill. Some

biographers state that he fainted when he first heard gunfire, while others deny this account. On August 16, 1860, Sachinomiya was proclaimed as the crown prince, and was formally adopted by his father's consort. Later that year, he was given an adult name, Mutsuhito. The

prince began his education at the age of nine. He was an indifferent

student, and, later in life, wrote poems regretting that he had not

applied himself more in writing practice. By

the early 1860s, the shogunate was under several threats.

Representatives of foreign powers sought to increase their influence in

Japan. Many daimyo were increasingly dissatisfied with bakufu handling of foreign affairs. Large numbers of young samurai, known as shishi or "men of high purpose" began to meet and speak against the shogunate. The shishi revered

the Emperor Kōmei and favored direct violent action to cure societal

ills. While they initially desired the death or expulsion of all

foreigners, the shishi would later prove more pragmatic, and begin to advocate the modernization of the country. The bakufu enacted several measures to appease the various groups, and hoped to drive a wedge between the shishi and daimyo. Kyoto was a major center for the shishi, who had influence over the Emperor Kōmei. In 1863, they persuaded him to issue an "Order to expel barbarians".

The Order placed the shogunate in a difficult position, since it knew

it lacked the power to do so. Several attacks were made on foreigners

or their ships, and foreign forces retaliated. Bakufu forces were able to drive most of the shishi out of Kyoto, and an attempt by them to return in 1864 was driven back. Neverless, unrest continued throughout Japan. The prince's awareness of the political turmoil is uncertain. During this time, he studied tanka poetry, first with his father, then with the court poets. As the prince continued his classical education in 1866, a new shogun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu took

office, a reformer who desired to transform Japan into a Western-style

state. Yoshinobu, who would prove to be the final shogun, was met with

resistance from among the bukufu, even as unrest and military actions continued. In mid-1866, a bakufu army set forth to punish rebels in southern Japan. The army was defeated. The

Emperor Kōmei had always enjoyed excellent health, and was only

36 years old in January 1867. In that month, however, he fell

seriously ill. He appeared to be recovering from his illness, but

suddenly worsened and died on January 30. Many historians believe the

Emperor Kōmei was poisoned, a view not unknown at the time: British

diplomat Sir Ernest Satow wrote,

"it is impossible to deny that [the Emperor Kōmei's] disappearance from

the political scene, leaving as his successor a boy of fifteen or

sixteen [actually fourteen], was most opportune". The crown prince formally ascended to the throne on February 13, 1867, in a brief ceremony in Kyoto. The

new Emperor continued his classical education, which did not include

matters of politics. In the meantime, the shogun, Yoshinobu, struggled

to maintain power. He repeatedly asked for the Emperor's confirmation

of his actions, which was eventually granted, but there is no

indication that the young Emperor was himself involved in the

decisions. The shishi and

other rebels continued to shape their vision of the new Japan, and

while they revered the Emperor, they had no thought of having him play

an active part in the political process. The

political struggle reached its climax in late 1867. In November, an

agreement was reached by which Yoshinobu would maintain his title and

some of his power, but the lawmaking power would be vested in a

bicameral legislature on the British model. The following month, the

agreement fell apart as the rebels marched on Kyoto, taking control of

the Imperial Palace. On

January 4, 1868, the Emperor ceremoniously read out a document before

the court proclaiming the "resoration" of Imperial rule, and the following month, documents were sent to foreign powers: The

Emperor of Japan announces to the sovereigns of all foreign countries

and to their subjects that permission has been granted to the Shogun

Tokugawa Yoshinobu to return the governing power in accordance with his

own request. We shall henceforward exercise supreme authority in all

the internal and external affairs of the country. Consequently the

title of Emperor must be substituted for that of Tycoon,

in which the treaties have been made. Officers are being appointed by

us to the conduct of foreign affairs. It is desirable that the

representatives of the treaty powers recognize this announcement. Yoshinobu resisted only briefly, but it was not until late 1869 that the final bakufu holdouts were finally defeated. In the ninth month of the following year, the era was

changed to Meiji, or “enlightened rule”, which was later used for the

emperor's posthumous name. This marked the beginning of the custom of

an era coinciding with an emperor's reign, and posthumously naming the

emperor after the era during which he ruled. Soon after his accession, the Emperor's officials presented Ichijō Haruko to

him as a possible bride. The future Empress was the daughter of an

Imperial official, and was three years older than the groom, who would

have to wait to wed until after his gembuku (manhood ceremony). The two married on January 11, 1869. Known posthumously as Empress Shōken, she was the first Imperial Consort to receive the title of kōgō (literally, the Emperor's wife, translated as Empress Consort),

in several hundred years. Although she was the first Japanese Empress

Consort to play a public role, she bore no children. However, the Meiji

emperor had fifteen children by five official ladies-in-waiting. Only

five of his children, a prince born to Lady Naruko (1855–1943), the

daughter of Yanagiwara Mitsunaru, and four princesses born to Lady

Sachiko (1867–1947), the eldest daughter of Count Sono Motosachi, lived to adulthood. Despite the ouster of the bakufu,

no effective central government had been put in place by the rebels. On

March 23, foreign envoys were first permitted to visit Kyoto and pay

formal calls on the Emperor. On April 7, 1868, the Emperor was presented with the Charter Oath,

a five-point statement of the nature of the new government, designed to

win over those who had not yet committed themselves to the new regime.

This document, which the Emperor then formally promulgated, abolished feudalism and

proclaimed a modern democratic government for Japan. The Charter Oath

would later be cited as support for the imposed changes in Japanese

government following World War II. In

mid-May, he left the Imperial precincts in Kyoto for the first time

since early childhood to take command of the forces pursuing the

remnants of the bakufu armies. Traveling in slow stages, he took three days to travel from Kyoto to Osaka, through roads lined with crowds. There

was no conflict in Osaka; the new leaders wanted the Emperor to be more

visible to his people and to foreign envoys. At the end of May, after

two weeks in Osaka (in a much less formal atmosphere than in Kyoto),

the Emperor returned to his home. Shortly

after his return, it was announced that the Emperor would begin to

preside over all state business, reserving further literary study for

his leisure time. It would not be until 1871 that the Emperor's studies included materials on contemporary affairs. On September 19, 1868, the Emperor announced that the name of the city of Edo was being changed to Tokyo,

or "eastern capital". He was formally crowned in Kyoto on October 15 (a

ceremony which had been postponed from the previous year due to the

unrest). Shortly before the coronation, he announced that the new era,

or nengō, would be called Meiji or "enlightened rule". Heretofore the nengō had often been changed multiple times in an emperoro's reign; from now on, it was announced, there would only be one nengō per reign. Soon after his coronation, the Emperor journeyed to Tokyo by road, visiting it for the first time. He arrived in late November, and began an extended stay by distributing sake among

the population. The population of Tokyo was eager for an Imperial

visit; it had been the site of the Shogun's court and the population

feared that with the abolition of the shogunate, the city might fall

into decline. It would not be until 1889 that a final decision was made to move the capital to Tokyo. While

in Tokyo, the Emperor boarded a Japanese naval vessel for the first

time, and the following day gave instructions for studies to see how

Japan's navy could be strengthened. Soon after his return to Kyoto, a rescript was

issued in the Emperor's name (but most likely written by court

officials). It indicated his intent to be involved in government

affairs, and indeed he attended cabinet meetings and innumerable other

government functions, though rarely speaking, almost until the day of

his death. The

successful revolutionaries organized themselves into a Council of

State, and subsequently into a system where three main ministers led

the government. This structure would last until the establishment of a

prime minister, who would lead a cabinet in the western fashion, in

1885. Initially, not even the retention of the emperor was certain; revolutionary leader Gotō Shōjirō later stated that some officials "were afraid the extremists might go further and abolish the Mikado". Japan's new leaders sought to reform the patchwork system of domains governed by the daimyo. In 1869, several of the daimyo who

had supported the revolution gave their lands to the Emperor and were

reappointed as governors, with considerable salaries. By the following

year, all other daimyo had followed suit. In 1871, the Emperor announced that domains were entirely abolished, as Japan was organized into 72 prefectures. The daimyo were

compensated with annual salaries equal to ten percent of their former

revenues (from which they did not now have to deduct the cost of

governing), but were required to move to the new capital, Tokyo. Most

retired from politics. Most samurai privileges were gradually abolished, as were their right to a stipend from the government. However, unlike the daimyo,

many samurai suffered financially from this change. Most other

class-based distinctions were abolished. Legalized discrimination

against the burakumin was ended. However, these classes continue to suffer discrimination in Japan to the present time. Although a parliament was

formed, it had no real power, and neither did the emperor. Power had

passed from the Tokugawa into the hands of those Daimyo and other

samurai who had led the Restoration. Japan was thus controlled by the Genro, an oligarchy,

which comprised the most powerful men of the military, political, and

economic spheres. The emperor, if nothing else, showed greater

political longevity than his recent predecessors, as he was the first

Japanese monarch to remain on the throne past the age of 50 since the

abdication of Emperor Ōgimachi in 1586. The

Meiji Restoration is a source of pride for the Japanese, as it and the

accompanying industrialization allowed Japan to become the preeminent

power in the Pacific and a major player in the world within a generation.

Yet, the Meiji emperor's role in the Restoration is debatable. He

certainly did not control Japan, but how much influence he wielded is

unknown. It is unlikely it will ever be clear whether he supported the Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) or the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905). One of the few windows we have into the Emperor's own feelings is his poetry, which seems to indicate a pacifist streak, or at least a man who wished war could be avoided. He composed the following pacifist poem or tanka: Near the end of his life several anarchists, including Kotoku Shusui, were executed on charges of having conspired to murder the sovereign. This conspiracy was known as the High Treason Incident.

Mutsuhito