<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Yutaka Taniyama, 1927

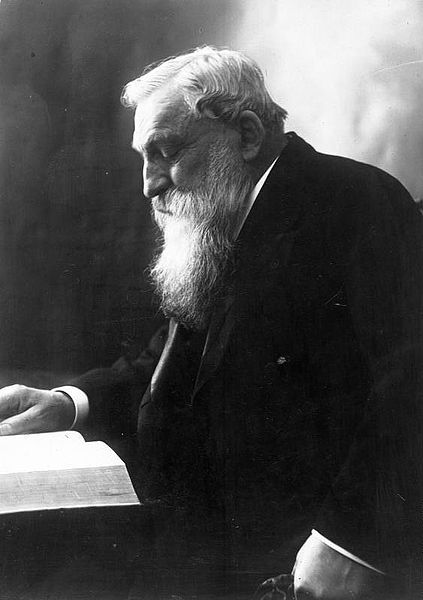

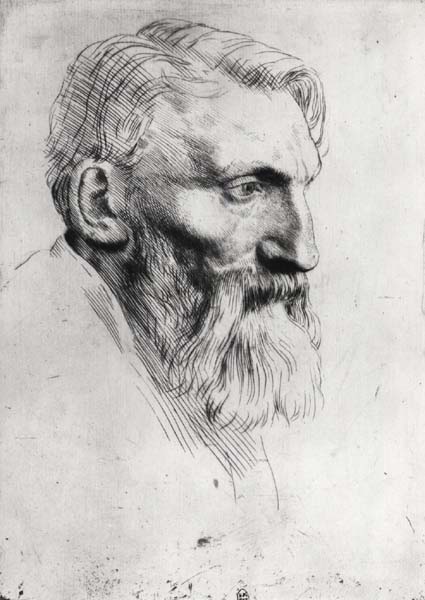

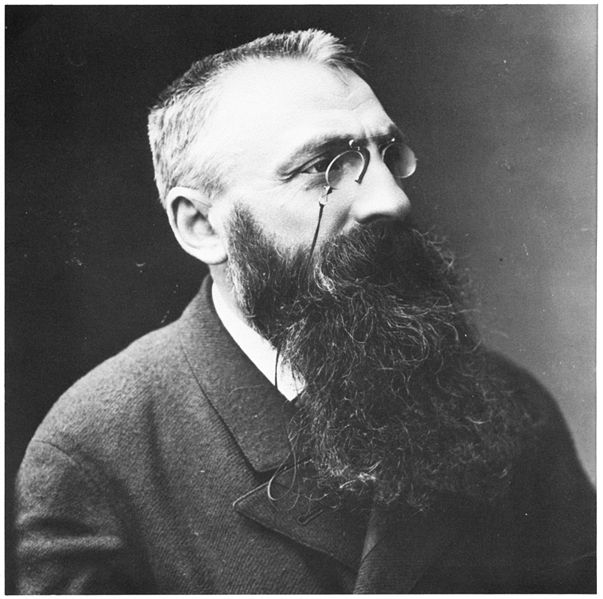

- Sculptor François Auguste René Rodin, 1840

- French Admiral Louis Antoine comte de Bougainville, 1729

PAGE SPONSOR

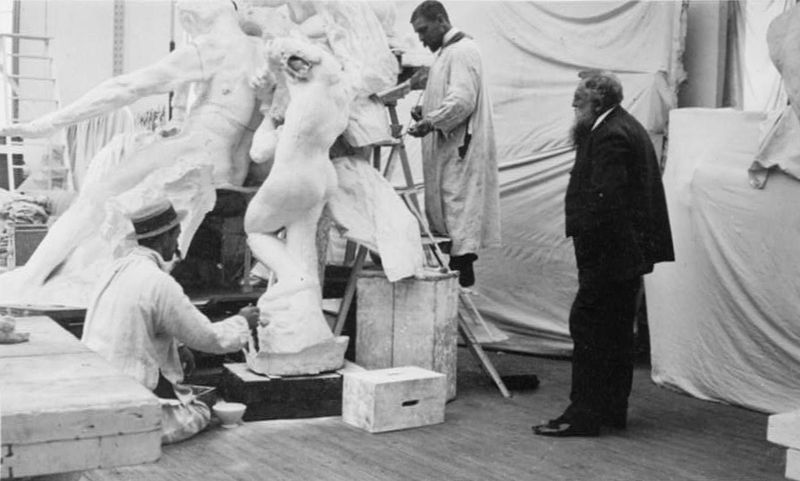

Auguste Rodin (born François-Auguste-René Rodin; 12 November 1840 – 17 November 1917) was a French sculptor. Although Rodin is generally considered the progenitor of modern sculpture, he did not set out to rebel against the past. He was schooled traditionally, took a craftsman-like approach to his work, and desired academic recognition, although he was never accepted into Paris's foremost school of art. Sculpturally, he possessed a unique ability to model a complex, turbulent, deeply pocketed surface in clay. Many of Rodin's most notable sculptures were roundly criticized during his lifetime. They clashed with the predominant figure sculpture tradition, in which works were decorative, formulaic, or highly thematic. Rodin's most original work departed from traditional themes of mythology and allegory, modeled the human body with realism, and celebrated individual character and physicality. Rodin was sensitive of the controversy surrounding his work, but refused to change his style. Successive works brought increasing favor from the government and the artistic community.

From

the unexpected realism of his first major figure — inspired by his 1875

trip to Italy — to the unconventional memorials whose commissions he

later sought, Rodin's reputation grew, such that he became the

preeminent French sculptor of his time. By 1900, he was a

world-renowned artist. Wealthy private clients sought Rodin's work

after his World's Fair exhibit,

and he kept company with a variety of high-profile intellectuals and

artists. He married his life-long companion, Rose Beuret, in the last

year of both their lives. His sculpture suffered a decline in

popularity after his death in 1917, but within a few decades his legacy

solidified. Rodin remains one of the few sculptors widely known outside

the visual arts community. Rodin

was born in 1840 into a working-class family in Paris, the second child

of Marie Cheffer and Jean-Baptiste Rodin, who was a police department

clerk. He was largely self-educated, and began to draw at ten. Between ages 14 and 17, Rodin attended the Petite École, a school specializing in art and mathematics, where he studied drawing and painting. His drawing teacher, Horace Lecoq de Boisbaudran,

believed in first developing the personality of his students such that

they observed with their own eyes and drew from their recollections.

Rodin still expressed appreciation for his teacher much later in life. There he first met Jules Dalou and Alphonse Legros. Rodin submitted a clay model of a companion to the Grand École in 1857 in an attempt to win entrance; he did not succeed, and two further applications were also denied. Given that entrance requirements at the Grand École were not particularly high, the rejections were considerable setbacks. Rodin's inability to gain entrance may have been due to the judges' Neoclassical tastes, while Rodin had been schooled in light, eighteenth-century sculpture. Leaving the Petite École in

1857, Rodin would earn a living as a craftsman and ornamenter for most

of the next two decades, producing decorative objects and architectural

embellishments. Rodin's sister Maria, two years his senior, died of peritonitis in

a convent in 1862. Her brother was anguished, and felt guilty because

he had introduced Maria to an unfaithful suitor. Turning away from art,

Rodin briefly joined a Catholic order. Father Peter Julian Eymard recognized

Rodin's talent and, sensing his lack of suitability for the order,

encouraged Rodin to continue with his sculpture. He returned to work as

a decorator, while taking classes with animal sculptor Antoine-Louis Barye. The teacher's attention to detail — his finely rendered musculature of animals in motion — significantly influenced Rodin. In

1864, Rodin began to live with a young seamstress named Rose Beuret,

with whom he would stay — with ranging commitment — for the rest of his

life. The couple bore a son, Auguste-Eugène Beuret (1866–1934). That year, Rodin offered his first sculpture for exhibition, and entered the studio of Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse, a successful mass producer of objets d'art.

Rodin worked as Carrier-Belleuse' chief assistant until 1870, designing

roof decorations and staircase and doorway embellishments. With the

arrival of the Franco-Prussian War, Rodin was called to serve in the National Guard, but his service was brief due to his near-sightedness. Decorators'

work had dwindled because of the war, yet Rodin needed to support his

family — poverty was a continual difficulty for Rodin until about the age

of 30. Carrier-Belleuse soon asked Rodin to join him in Belgium, where they would work on ornamentation for Brussels' bourse. Rodin planned to stay in Belgium a few months, but he spent the next six years abroad. It was a pivotal time in Rodin's life. He

had acquired skill and experience as a craftsman, but no one had yet

seen his art, which sat in his workshop, since Rodin could not afford

castings. Though his relationship with Carrier-Belleuse deteriorated,

he found other employment in Brussels, displayed some works at salons,

and his companion Rose soon joined him there. Having saved enough money

to travel, Rodin visited Italy for two months in 1875, where he was

drawn to the work of Donatello and Michelangelo. Their work had a profound effect on his artistic direction. Rodin said, "It is Michelangelo who has freed me from academic sculpture." Returning to Belgium, he began work on The Age of Bronze, a life-size male figure whose realism brought Rodin attention but led to accusations of sculptural cheating. Rose Beuret and Rodin returned to Paris in 1877, moving into a small flat on the Left Bank.

Misfortune surrounded Rodin: his mother, who had wanted to see her son

marry, was dead, and his father was blind and senile, cared for by

Rodin's sister-in-law, Aunt Thérèse. Rodin's

eleven-year-old son Auguste, possibly developmentally delayed, was also

in the ever-helpful Thérèse's care. Rodin had essentially

abandoned his son for six years, and

would have a very limited relationship with him throughout his life.

Father and son now joined the couple in their flat, with Rose as

caretaker. The charges of fakery surrounding The Age of Bronze continued.

Rodin increasingly sought more soothing female companionship in Paris,

and Rose stayed in the background. Rodin earned his living

collaborating with more established sculptors on public commissions,

primarily memorials and neo-baroque architectural pieces in the style of Carpeaux. In competitions for commissions he submitted models of Denis Diderot, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Lazare Carnot, all to no avail. On his own time, he worked on studies leading to the creation of his next important work, St. John the Baptist Preaching. In 1880, Carrier-Belleuse — now art director of the Sèvres national porcelain factory — offered

Rodin a part-time position as a designer. The offer was in part a

gesture of reconciliation, and Rodin accepted. That part of Rodin which

appreciated eighteenth-century tastes was aroused, and he immersed

himself in designs for vases and table ornaments that brought the

factory renown across Europe. The artistic community appreciated his work in this vein, and Rodin was invited to Paris Salons by such friends as writer Léon Cladel. During his early appearances at these social events, Rodin seemed shy; in

his later years, as his fame grew, he displayed the loquaciousness and

temperament for which he is better known. French statesman Leon Gambetta expressed

a desire to meet Rodin, and the sculptor impressed him when they met at

a salon. Gambetta spoke of Rodin in turn to several government

ministers, likely including Edmund Turquet, the Undersecretary of the

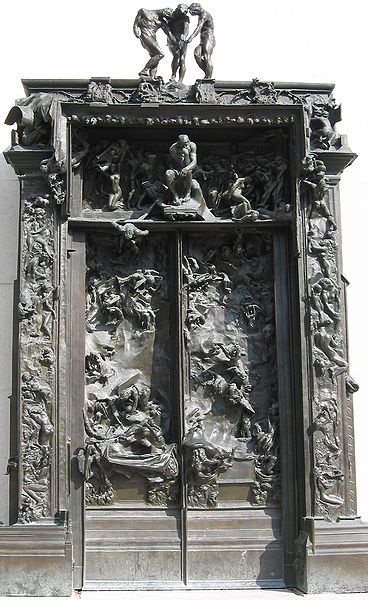

Ministry of Fine Arts, whom Rodin eventually met. Rodin's relationship with Turquet was rewarding: through him, he won the 1880 commission to create a portal for a planned museum of decorative arts. Rodin dedicated much of the next four decades to his elaborate Gates of Hell,

an unfinished portal for a museum that was never built. Many of the

portal's figures became sculptures in themselves, including Rodin's most famous, The Thinker and The Kiss.

With the museum commission came a free studio, granting Rodin a new

level of artistic freedom. Soon, he stopped working at the porcelain

factory; his income came from private commissions. In 1883, Rodin agreed to supervise a course for sculptor Alfred Boucher in his absence, where he met the 18-year-old Camille Claudel. The two formed a passionate but stormy relationship and influenced each

other artistically. Claudel inspired Rodin as a model for many of his

figures, and she was a talented sculptor, assisting him on commissions. Although busy with The Gates of Hell, Rodin won other commissions. He pursued an opportunity to create a historical monument for the town of Calais. For a monument to French author Honoré de Balzac,

Rodin was chosen in 1891. His execution of both sculptures clashed with

traditional tastes, and met with varying degrees of disapproval from

the organizations that sponsored the commissions. Still, Rodin was

gaining support from diverse sources that propelled him toward fame. In

1889, the Paris Salon invited Rodin to be a judge on its artistic jury.

Though Rodin's career was on the rise, Claudel and Beuret were becoming

increasingly impatient with Rodin's "double life". Claudel and Rodin

shared an atelier at

a small old castle, but Rodin refused to relinquish his ties to Beuret,

his loyal companion during the lean years, and mother of his son.

During one absence, Rodin wrote to Beuret, "I think of how much you

must have loved me to put up with my caprices…I remain, in all

tenderness, your Rodin." Claudel and Rodin parted in 1898. Claudel suffered a nervous breakdown several years later and was confined to an institution by her family until her death.

In 1864, Rodin submitted his first sculpture for exhibition, The Man with the Broken Nose, to the Paris Salon. The subject was an elderly neighbourhood street porter. The unconventional bronze piece was not a traditional bust,

but instead the head was "broken off" at the neck, the nose was

flattened and crooked, and the back of the head was absent, having

fallen off the clay model in an accident. The work emphasized texture

and the emotional state of the subject; it illustrated the

"unfinishedness" that would characterize many of Rodin's later

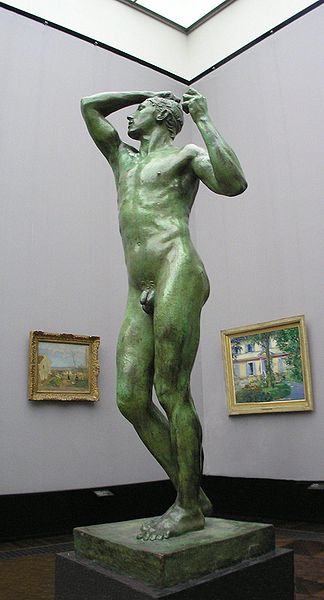

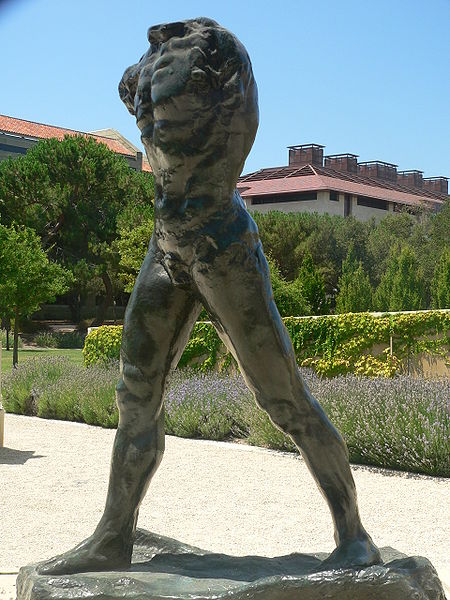

sculptures. The Salon rejected the piece. In Brussels, Rodin created his first full-scale work, The Age of Bronze, having returned from Italy. Modelled by a Belgian soldier, the figure drew inspiration from Michelangelo's Dying Slave, which Rodin had observed at the Louvre.

Attempting to combine Michelangelo's mastery of the human form with his

own sense of human nature, Rodin studied his model from all angles, at

rest and in motion; he mounted a ladder for additional perspective, and

made clay models, which he studied by candlelight. The result was a

life-size, well-proportioned nude figure, posed unconventionally with

his right hand atop his head, and his left arm held out at his side,

forearm parallel to the body. In

1877, the work debuted in Brussels and then was shown at the Paris

Salon. The statue's apparent lack of a theme was troubling to

critics — commemorating neither mythology nor a noble historical

event — and it is not clear whether Rodin intended a theme. He first titled the work The Vanquished,

in which form the left hand held a spear, but he removed the spear

because it obstructed the torso from certain angles. After two more

intermediary titles, Rodin settled on The Age of Bronze, suggesting the Bronze Age,

and in Rodin's words, "man arising from nature". Later, however, Rodin

said that he had had in mind "just a simple piece of sculpture without

reference to subject". Its mastery of form, light, and shadow made the work look so realistic that Rodin was accused of surmoulage — having

taken a cast from a living model. Rodin vigorously denied the charges,

writing to newspapers and having photographs taken of the model to

prove how the sculpture differed. He demanded an inquiry and was

eventually exonerated by a committee of sculptors. Leaving aside the

false charges, the piece polarized critics. It had barely won

acceptance for display at the Paris Salon, and criticism likened it to

"a statue of a sleepwalker" and called it "an astonishingly accurate

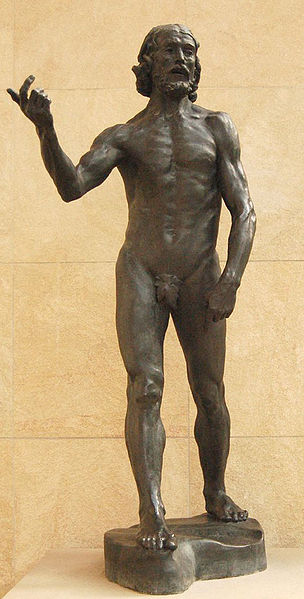

copy of a low type". Others rallied to defend the piece and Rodin's integrity. The government minister Turquet admired the piece, and The Age of Bronze was purchased by the state for 2,200 francs — what it had cost Rodin to have it cast in bronze. A second male nude, St. John the Baptist Preaching, was completed in 1878. Rodin sought to avoid another charge of surmoulage by making the statue larger than life: St. John stands almost 6' 7'' (2 m). While the The Age of Bronze is statically posed, St. John gestures

and seems to move toward the viewer. The effect of walking is achieved

despite the figure having both feet firmly on the ground — a physical

impossibility, and a technical achievement that was lost on most

contemporary critics. Rodin chose this contradictory position to, in his words, "display

simultaneously…views of an object which in fact can be seen only

successively". Despite the title, St. John the Baptist Preaching did

not have an obviously religious theme. The model, an Italian peasant

who presented himself at Rodin's studio, possessed an idiosyncratic

sense of movement that Rodin felt compelled to capture. Rodin thought of John the Baptist, and carried that association into the title of the work. In

1880, Rodin submitted the sculpture to the Paris Salon. Critics were

still mostly dismissive of his work, but the piece finished third in

the Salon's sculpture category. Regardless of the immediate receptions of St. John and The Age of Bronze, Rodin had achieved a new degree of fame. Students sought him at his studio, praising his work and scorning the charges of surmoulage. The artistic community knew his name. A commission to create a portal for Paris' planned Museum of Decorative Arts was awarded to Rodin in 1880. Although the museum was never built, Rodin worked throughout his life on The Gates of Hell, a monumental sculptural group depicting scenes from Dante's Inferno in

high relief. Often lacking a clear conception of his major works, Rodin

compensated with hard work and a striving for perfection. He conceived The Gates with the surmoulage controversy still in mind: "…I had made the St. John to

refute [the charges of casting from a model], but it only partially

succeeded. To prove completely that I could model from life as well as

other sculptors, I determined…to make the sculpture on the door of

figures smaller than life." Laws of composition gave way to the Gates' disordered

and untamed depiction of Hell. The figures and groups in this, Rodin's

meditation on the condition of man, are physically and morally isolated

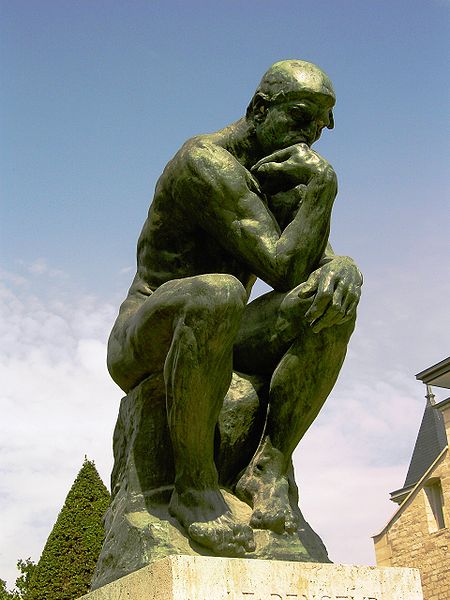

in their torment. The Gates of Hell comprised 186 figures in its final form. Many of Rodin's best-known sculptures started as designs of figures for this composition, such as The Thinker, The Three Shades, and The Kiss, and were only later presented as separate and independent works. Other well-known works derived from The Gates are Ugolino, Fugit Amor, The Falling Man, and The Prodigal Son. The Thinker (originally titled The Poet,

after Dante) was to become one of the most well-known sculptures in the

world. The original was a 27.5-inch (700 mm)-high bronze piece

created between 1879 and 1889, designed for the Gates' lintel, from which the figure would gaze down upon Hell. While The Thinker most obviously characterizes Dante, aspects of the Biblical Adam, the mythological Prometheus, and Rodin himself have been ascribed to him. Other observers de-emphasize the apparent intellectual theme of The Thinker, stressing the figure's rough physicality and the emotional tension emanating from it. The

town of Calais had contemplated an historical monument for decades when

Rodin learned of the project. He pursued the commission, interested in

the medieval motif and patriotic theme. The mayor of Calais was tempted

to hire Rodin on the spot upon visiting his studio, and soon the

memorial was approved, with Rodin as its architect. It would

commemorate the six townspeople of Calais who offered their lives to

save their fellow citizens. During the Hundred Years' War, the army of King Edward III besieged Calais, and Edward ordered that the town's population be killed en masse.

He agreed to spare them if six of the principal citizens would come to

him prepared to die, bareheaded and barefooted and with ropes around

their necks. When they came, he ordered that they be executed, but

pardoned them when his queen, Philippa of Hainault, begged him to spare their lives. The Burghers of Calais depicts

the men as they are leaving for the king's camp, carrying keys to the

town's gates and citadel. Rodin began the project in 1884, inspired by

the chronicles of the siege by Jean Froissart. Though the town envisioned an allegorical,

heroic piece centered on Eustache de Saint-Pierre, the eldest of the

six men, Rodin conceived the sculpture as a study in the varied and

complex emotions under which all six men were laboring. One year into

the commission, the Calais committee was not impressed with Rodin's

progress. Rodin indicated his willingness to end the project rather

than change his design to meet the committee's conservative

expectations, but Calais said to continue. In 1889, The Burghers of Calais was

first displayed to general acclaim. It is a bronze sculpture weighing

two tons (1,814 kg), and its figures are 6.6 ft (2 m)

tall. The six men portrayed do not display a united, heroic front; rather,

each is isolated from his brothers, individually deliberating and

struggling with his expected fate. Rodin soon proposed that the

monument's high pedestal be eliminated, wanting to move the sculpture

to ground level so that viewers could "penetrate to the heart of the

subject". At ground level, the figures' positions lead the viewer around the work, and subtly suggest their common movement forward. The committee was incensed by the untraditional proposal, but Rodin would not yield. In 1895, Calais succeeded in having Burghers displayed

in their preferred form: the work was placed in front of a public

garden on a high platform, surrounded by a cast-iron railing. Rodin had

wanted it located near the town hall, where it would engage the public.

Only after damage during the First World War, subsequent storage, and

Rodin's death was the sculpture displayed as he had intended. It is one

of Rodin's most well-known and acclaimed works. Commissioned to create a monument to French writer Victor Hugo in 1889, Rodin dealt extensively with the subject of artist and muse. Like many of Rodin's public commissions, Monument to Victor Hugo was met with resistance because it did not fit conventional expectations. Commenting on Rodin's monument to Victor Hugo, The Times in

1909 expressed that "there is some show of reason in the complaint that

[Rodin's] conceptions are sometimes unsuited to his medium, and that in

such cases they overstrain his vast technical powers". The 1897 plaster model was not cast in bronze until 1964. The Société des Gens des Lettres, a Parisian organization of writers, planned a monument to French novelist Honoré de Balzac immediately after his death in 1850. The society commissioned Rodin to create the

memorial in 1891, and Rodin spent years developing the concept for his

sculpture. Challenged in finding an appropriate representation of

Balzac given the author's rotund physique, Rodin produced many studies:

portraits, full-length figures in the nude, wearing a frock coat, or in a robe — a

replica of which Rodin had requested. The realized sculpture displays

Balzac cloaked in the drapery, looking forcefully into the distance

with deeply gouged features. Rodin's intent had been to show Balzac at

the moment of conceiving a work — to express courage, labor, and struggle. When Balzac was exhibited in 1898, the negative reaction was not surprising. The Société rejected the work, and the press ran parodies. Criticizing the work, Morey (1918) reflected, "there may come a time, and doubtless will come a time, when it will not seem outre to

represent a great novelist as a huge comic mask crowning a bathrobe,

but even at the present day this statue impresses one as slang." A modern critic, indeed, indicates that Balzac is one of Rodin's masterpieces. The monument had its supporters in Rodin's day; a manifesto defending him was signed by Monet, Debussy, and future Premier Georges Clemenceau, among many others. Rather than try to convince skeptics of the merit of the monument, Rodin repaid the Société his

commission and moved the figure to his garden. After this experience,

Rodin did not complete another public commission. Only in 1939 was Monument to Balzac cast in bronze. The

popularity of Rodin's most famous sculptures tends to obscure his total

creative output. A prolific artist, he created thousands of busts,

figures, and sculptural fragments over more than five decades. He

painted in oils (especially in his thirties) and in water colors. The Musée Rodin holds 7,000 of his drawings and prints, in chalk and charcoal, and thirteen vigorous drypoints. He also produced a single lithograph. Portraiture was an important component of Rodin's oeuvre, helping him to win acceptance and financial independence. His first sculpture was a bust of his father in 1860, and he produced at least 56 portraits between 1877 and his death in 1917. Early subjects included fellow sculptor Jules Dalou (1883)

and companion Camille Claudel (1884). Later, with his reputation

established, Rodin made busts of prominent contemporaries such as

English politician George Wyndham (1905), Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw (1906), Austrian composer Gustav Mahler (1909), former Argentinian president Domingo Faustino Sarmiento and French statesman Georges Clemenceau (1911). Rodin was a naturalist, less concerned with monumental expression than with character and emotion. Departing with centuries of tradition, he turned away from the idealism of the Greeks, and the decorative beauty of the Baroque and neo-Baroque movements.

His sculpture emphasized the individual and the concreteness of flesh,

and suggested emotion through detailed, textured surfaces, and the

interplay of light and shadow. To a greater degree than his

contemporaries, Rodin believed that an individual's character was

revealed by his physical features. Rodin's talent for surface modeling allowed him to let every part of the body speak for the whole. The male's passion in The Kiss is suggested by the grip of his toes on the rock, the rigidness of his back, and the differentiation of his hands. Speaking of The Thinker,

Rodin illuminated his aesthetic: "What makes my Thinker think is that

he thinks not only with his brain, with his knitted brow, his distended

nostrils and compressed lips, but with every muscle of his arms, back,

and legs, with his clenched fist and gripping toes." Sculptural

fragments to Rodin were autonomous works, and he considered them the

essence of his artistic statement. His fragments — perhaps lacking arms,

legs, or a head — took sculpture further from its traditional role of

portraying likenesses, and into a realm where forms existed for their

own sake. Notable examples are The Walking Man, Meditation without Arms, and Iris, Messenger of the Gods. Rodin

saw suffering and conflict as hallmarks of modern art. "Nothing,

really, is more moving than the maddened beast, dying from unfulfilled

desire and asking in vain for grace to quell its passion." Charles Baudelaire echoed those themes, and was among Rodin's favorite poets. Rodin enjoyed music, especially the opera composer Gluck, and wrote a book about French cathedrals. He owned a work by the as-yet-unrecognized Van Gogh, and admired the forgotten El Greco. Instead

of copying traditional academic postures, Rodin preferred to work with

amateur models, street performers, acrobats, strong men, and dancers.

In the atelier, his models moved about and took positions without

manipulation. Very

devoted to his craft, Rodin worked constantly but not feverishly. The

sculptor made quick sketches in clay that were later fine-tuned, cast

in plaster, and forged into bronze or carved in marble. Rodin was

fascinated by dance and spontaneous movement. As France's best-known

sculptor, he had a large staff of pupils, craftsmen, and stone cutters

working for him, including the Czech sculptors Josef Maratka and Joseph

Kratina. Through his method of marcottage

(layering),

he used the same sculptural elements time and time again, under

different names and in different combinations. Disliking the formality

of pedestals, Rodin placed many of his subjects around rough rock to emphasize their immediacy and provide contrast. George

Bernard Shaw sat for a portrait and gave an idea of Rodin's technique:

"While he worked, he achieved a number of miracles. At the end of the

first fifteen minutes, after having given a simple idea of the human

form to the block of clay, he produced by the action of his thumb a

bust so living that I would have taken it away with me to relieve the

sculptor of any further work." He described the evolution of his bust

over a month, passing through "all the stages of art's evolution":

first, a "Byzantine masterpiece", then "Bernini intermingled", then an elegant Houdon. "The hand of Rodin worked not as the hand of a sculptor works, but as the work of Elan Vital. The Hand of God is his own hand." By 1900, Rodin's artistic reputation was entrenched. Gaining exposure from a pavilion of his artwork set up near the 1900 World's Fair (Exposition Universelle) in Paris, he received requests to make busts of prominent people internationally, while

his assistants at the atelier produced duplicates of his works. His

income from portrait commissions alone totalled probably 200,000 francs

a year. As Rodin's fame grew, he attracted many followers, including the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke, and authors Octave Mirbeau, Joris-Karl Huysmans, and Oscar Wilde. Rilke stayed with Rodin in 1905 and 1906, and did administrative work for him; he would later write a laudatory monograph on the sculptor. Rodin and Beuret's modest country estate in Meudon, purchased in 1897, was a host to such visitors as King Edward, dancer Isadora Duncan, and harpsichordist Wanda Landowska. Rodin moved to the city in 1908, renting the main floor of the Hôtel Biron, an eighteenth-century townhouse. He left Beuret in Meudon, and began an affair with the American-born Duchesse de Choiseul. Among Rodin's overseas admirers were the transit magnate Charles Tyson Yerkes and the historian Henry Brooks Adams; Yerkes is reputed to have been the first American to own a Rodin sculpture. After

the turn of the century, Rodin was a regular visitor to Great Britain,

where he developed a loyal following by the beginning of the First

World War. He first visited England in 1881, where his friend, the

artist Alphonse Legros, had introduced him to the poet William Ernest Henley. With his personal connections and enthusiasm for Rodin's art, Henley was most responsible for Rodin's reception in Britain. (Rodin later returned the favor by sculpting a bust of Henley that was used as the frontispiece to Henley's collected works and, after his death, on his monument in London.) Through Henley, Rodin met Robert Louis Stevenson and Robert Browning, in whom he found further support. Encouraged

by the enthusiasm of British artists, students, and high society for

his art, Rodin donated a significant selection of his works to the

nation in 1914. After the revitalization of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1890, Rodin served as the body's vice-president. In 1903, Rodin was elected president of the International Society of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers. He replaced its former president, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, upon Whistler's death. His election to the prestigious position was largely due to the efforts of Albert Ludovici, father of English philosopher Anthony Ludovici. During

his later creative years, Rodin's work turned increasingly toward the

female form, and themes of more overt masculinity and femininity. He concentrated on small dance studies, and produced numerous erotic drawings, sketched in a loose way, without taking his pencil from the paper or his eyes from the model. Rodin met American dancer Isadora Duncan in 1900, attempted to seduce her, and

the next year sketched studies of her and her students. In July 1906,

Rodin was also enchanted by dancers from the Royal Ballet of Cambodia,

and produced some of his most famous drawings from the experience. Fifty-three

years into their relationship, Rodin married Rose Beuret. The wedding

was 29 January 1917, and Beuret died two weeks later, on 16 February. Rodin was ill that year; in January, he suffered weakness from influenza, and

on 16 November his physician announced that "congestion of the lungs

has caused great weakness. The patient's condition is grave." Rodin died the next day, age 77, at his villa in Meudon, Île-de-France, on the outskirts of Paris. A cast of The Thinker was placed next to his tomb in Meudon; it was Rodin's wish that the figure serve as his headstone and epitaph. In

1923, Marcell Tirel, Rodin's secretary, published a book alleging that

Rodin's death was largely due to cold, and the fact that he had no heat

at Meudon. Rodin requested permission to stay in the Hotel Biron, a museum of his works, but the director of the museum refused to let him stay there.